When Don Fisher stepped down as chief executive of the Gap in the late 1990s, he and his wife, Doris, decided that they wanted to tackle one of the most difficult social challenges in the United States: improving public education. Through an expert advisor, they learned about the Knowledge Is Power Program (KIPP), which at the time consisted of just two charter middle schools—one in Houston and one in New York City. And after lengthy due diligence, the Fishers committed to giving $15 million over three years (roughly three times the organization’s annual revenue at the time) to bring KIPP’s results- oriented methods to many more communities and students.

If you'd like to learn more about what it would take for your organization to be ready to receive a big bet, visit our "How to Position Your Nonprofit Organization for a Big Bet" toolkit.

The Fishers bet big, and they bet smart. KIPP schools make a real difference in the lives of their students: the majority of fifth graders enter KIPP with skills below grade level, but they move into high school with above-grade-level skills. KIPP alumni are graduating from college at rates that exceed the national average in all income groups and at more than four times the rate of the average student from a low-income community. In fact, KIPP’s success has been a large factor in pushing forward the charter school movement. “Their gift gave us permission to think big,” says KIPP CEO Richard Barth. “We would not have 183 schools today if Don hadn’t encouraged that kind of thinking.”

Many of today’s largest donors admire the Fishers’ bold commitment and the results it has helped produce. They say that they want to follow suit. A review of the public statements of US donors who have committed to the Giving Pledge and those listed in Forbes 50 Top Givers reveals that 60 percent articulate a powerful social change goal as their dominant philanthropic objective—eliminating disparities in health care, for example, or providing better educational opportunities for people in need. Nearly 80 percent state that such a goal is one of their two or three top priorities.

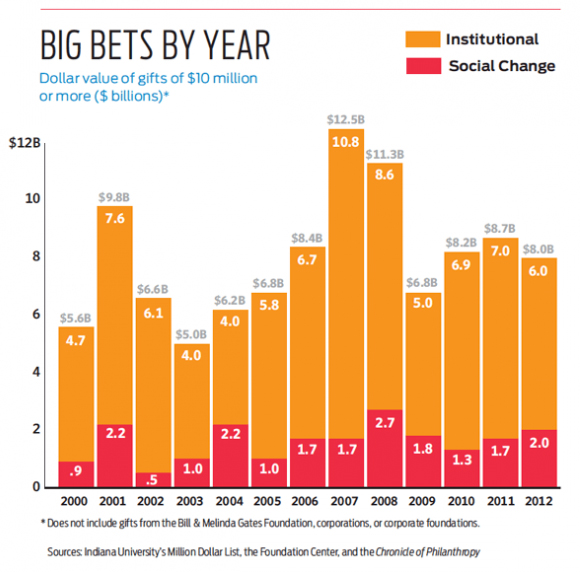

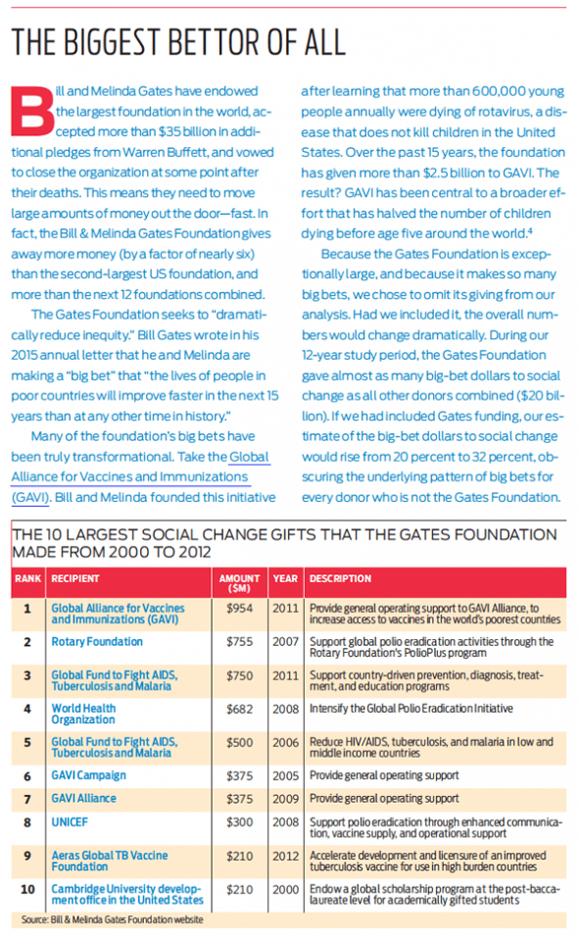

Yet our research found that only a modest proportion of the biggest philanthropic gifts is actually focused on these types of social change. Between 2000 and 2012, the total dollar volume of all announced philanthropic big bets (those of $10 million or more) by US donors averaged $8 billion a year. Nonprofits addressing social change received roughly 65 identifiable big bets annually, with a total value of approximately $1.6 billion a year. In other words, just 20 percent of big bets, by dollar value, went to the areas we categorize as social change giving. (See “Big Bets Methodology” below.) This proportion was roughly constant across the period of the analysis. (These figures do not include the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, because its size and its focus on big bets for social change would distort the results. See “The Biggest Bettor of All” below.)

The other 80 percent of big bets fall into what is best described as institutional giving—primarily to universities, hospitals, and cultural institutions. These entities are hugely important to society, but they are often already richly funded, with ample capacity to continue securing major gifts. (See “Big Bets by Year” below.)

Clearly, nonprofits and initiatives addressing social change have a fairly low market share of big bets. Their share is even lower among “giving-while-living” donors: Just 16 percent of big bet dollars from this set of engaged donors (either as individuals or through foundations they actively guide) went to social change, compared to 28 percent of those from other kinds of foundations and institutions.

Donors feel this “aspiration gap” in their philanthropy. For the last 16 years, The Bridgespan Group has counseled more than 50 of the world’s most generous and ambitious philanthropists. Many have said some version of “I can’t find enough opportunities to put large amounts of my money to work on the issues I really want to change.” They’ve spent years searching for such defining opportunities; they’re deeply frustrated; and they’re worried that they’re not making nearly the difference they could. Is their frustration warranted? Would more big bets really make a big difference? If the answer is “Yes” to both questions, then what are the barriers holding donors back, and how might those barriers be defeated?

Big Bets Methodology

Researching the frequency and impact of large philanthropic grants on social change organizations requires one to make choices. What constitutes a large grant? What type of organization is involved in social change, and what type isn’t? Below are answers to some of the most frequently asked questions about the methodology behind our work.

How did you define “big bet”? We targeted philanthropic commitments of $10 million or more to an organization or a defined initiative, such as reducing smoking. The donors could be either individuals or foundations, but not corporate foundations. The commitments could span multiple years and multiple named recipients. Our goal was to capture the point at which donors ceded control of the money, so we excluded gifts to donors’ own foundations or donor-advised funds, but included gifts to independent foundations as well as intermediaries that act as aggregators.

Why did you set the threshold at $10 million? We selected $10 million as the threshold for a big bet because it is low enough to capture major gifts in fields where organizations and initiatives tend to be smaller, yet high enough that gifts would have the potential to fuel significant change. We also wanted to have a manageable number of gifts to analyze. That’s not to say that $10 million is a magical giving level. In some fields and with some goals it could be that $5 million, or $100 million, is a more appropriate fit to the donor’s aspirations.

How did you define “social change”? We aimed for inclusivity and opted for a broad definition of social change, including all gifts to human services, the environment, and international development, save for a small minority that, upon individual review, clearly fell outside the social change realm (e.g., amusement parks). We did not include gifts to arts institutions, higher education institutions, medical institutions, or private K-12 schools unless donors stipulated the gift for anti-poverty initiatives or underfunded diseases that disproportionately affect low-income people. We included gifts to religious organizations only when the goal was human services or international development.

Why did you exclude the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation? We did not include the Gates Foundation because its sheer size (it’s the largest grantmaking foundation in the United States by a factor of three), and its slant to both big bets and social-change causes would have distorted the trends in the broader dataset. For the same reason, we omitted Warren Buffett’s gifts to the Gates Foundation.

What sources of data did you use? Our primary data source was Indiana University’s Million Dollar List, which tracks all publicly announced gifts of at least $1 million. We also relied on the Foundation Center’s dataset of gifts from the top 1,000 foundations and the Chronicle of Philanthropy’s annual “Philanthropy 50” list of top gifts by individuals.

Have you captured all big bets made over the 2000 to 2012 study period? We believe this research is the most comprehensive of its kind to date and that we’ve captured a majority of the big bets on social change. We have not, however, captured every single one. The absence of reporting requirements for individual giving means that we will have missed big bets that donors chose not to announce publicly. In addition, a multiyear big bet commitment (e.g., a $10 million gift spread over five years in $2 million increments) could slip below our radar if a donor were to announce the annual amounts rather than the overall tally. The same could be true of a big bet made to multiple organizations but not announced as a single initiative. If you know of gifts we may have omitted or improperly recorded, please let us know. Our goal is to continually build the comprehensiveness of this important data set.

Big Bets Matter

Intuitively, spreading donations around—“peanut butter philanthropy”— does not seem like the best path to change the world. At the same time, though, bigger is not always better. So before diving into the challenges facing donors who aspire to place big bets on social change efforts, it’s worth asking: How do we know that spurring more big bets on social change would make a correspondingly big difference?

Scientifically speaking, we don’t. There isn’t any definitive database of “success” in the social sector that would enable a comprehensive study of the correlation with philanthropic big bets. Nonetheless, the evidence we do have suggests that they matter a great deal. Gifts of $10 million or more are exceptionally rare; between 2000 and 2012, only 2 percent of even the largest US human services agencies (those with more than $10 million in annual revenue) received one. Yet such big bets seem to be behind a remarkable proportion of society’s most effective nonprofits and social movements. Consider the following broad evidence:

-

The book Forces for Good is based on a rigorous and respected assessment of the most successful nonprofit organizations. The authors screened hundreds of nonprofits to identify a dozen standouts. Their “winners” were groups like the Environmental Defense Fund, City Year, and Share Our Strength. Of these dozen, 11, or more than 90 percent, received a critical big bet.

-

Of the $10 million-plus organizations on the Social Impact Exchange’s 100 top nonprofits, 30 percent received a big bet.

- Big bets have also helped fuel social movements. Bridgespan assembled a list of 14 widely regarded social movement successes in recent decades— including, in the United States, the rejuvenation of conservatism in the 1970s and ’80s, LGBT rights in the last decade, and globally, the Green Revolution of the 1940s–’60s. More than 70 percent received at least one pivotal big bet.1

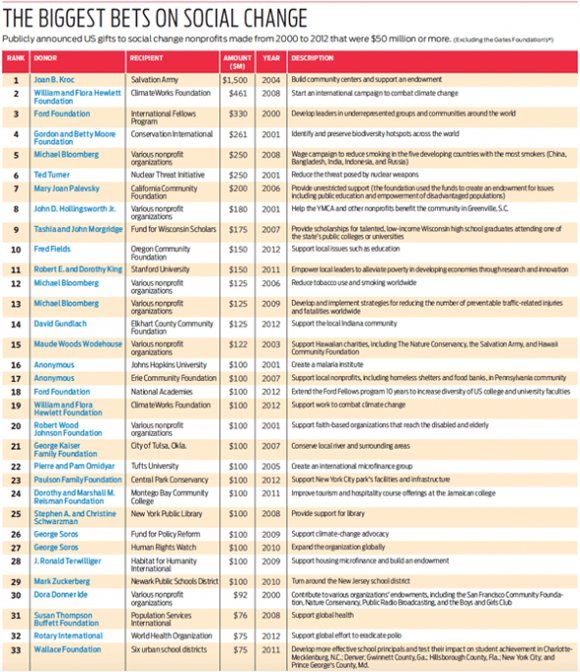

So why are big bets so powerful? They can radically change the organizations or movements they support— from acquiring critical tracts of land containing endangered species, to scaling up proven programs to new geographies, to launching advocacy campaigns. They can create a leap in their recipients’ abilities or long-term ambitions. (See “The Biggest Bets on Social Change” below.)

Consider the difference that Robert W. Wilson’s big-bet gift to The Nature Conservancy (TNC) made for that organization. (Wilson, a hedge-fund manager who died in 2013, was a serial big bettor—making other large gifts to the Environmental Defense Fund, the Wildlife Conservation Society, and the World Monuments Fund.) In the late 1990s, TNC was already large, with a mission to advance conservation around the world and a strong network of domestic donors. The challenge it faced was that some of the highest-impact work to be done was outside the United States, whereas its donor network centered on TNC’s state chapters. Wilson initiated a challenge to change that. Beginning in 1997 with a $10 million commitment, which ultimately grew to a total of $100 million over the next decade, Wilson matched any US donor’s international gift with a gift to the donor’s state chapter.

TNC raised $150 million from other donors as part of this challenge, enabling the organization to expand its global work dramatically— and transforming its US donors into champions of global conservation. A second challenge grant followed. And even though the challenge grants are over, the beneficial effect on TNC’s international fundraising endures. TNC’s annual international fundraising grew from $12 million in 1997 to more than $140 million in 2014. “Bob was maybe the best donor ever,” says Mark Tercek, TNC’s current CEO. “He was looking for bold ideas, and he had confidence in the organization’s leadership—the kind of confidence private sector investors usually need before they’ll invest big in a company.”

In our work with donors, we sometimes find great near-term opportunities to make big bets. Other times, modest pilots are the best path forward, to give organizations time to hone their programs and begin to demonstrate the results that would support something bigger. Ultimately, though, it takes a lot to do a lot. Philanthropic gifts need to be right-sized to the problems they address. Even $10 million, which is an enormous sum for anyone to earn or to have the generosity to give away, could be modest in comparison to many of the goals donors embrace, such as radically increasing the graduation rate of children in a community, slowing climate change, or ending human trafficking. Part of the power of philanthropy is that it can catalyze awareness and additional funding. But at the end of the day, big problems generally require big bets.

Why the Large Aspiration Gap?

If roughly 80 percent of the largest donors publicly aspire to social change, and there’s evidence that big bets can be a powerful tool to make a difference on the issues they care about, why are only 20 percent of all big bets going to social change? This question is not easily subjected to research, as it is most pertinent to a very limited number of people who, understandably, tend to be intensely private about their philanthropy. Bridgespan’s close counsel with a number of them—some of today’s most significant big bettors and a number more with the aspiration and capacity to become a big bettor—has given us a distinctive window into their motivations and actions. We consistently see two types of barriers: one related to finding and structuring deals, and the other to how donors, their peers, and the media think about big bets on social change.

Deal-Making Challenges

Placing a thoughtful big bet on a complex social-change issue is hard. Markets do not exist for nonprofit investments in the way they do for commercial ones, and information on impact can be hard to come by. We found three significant challenges to finding and structuring a big-bet deal.

Limited “shovel-ready” opportunities. Rare is the prospective donor to a university or hospital who has trouble finding an institution with the ability to make use of a big gift. But a capacity problem can be a real barrier for big bets on social change, where organizations that are effective enough and large enough to make good use of a big investment may, in some fields and some geographic areas, be few and far between. “There’s a relatively small number of organizations that can effectively metabolize seven- and eight-figure checks,” says James Jensen of the Jenesis Group. The Fishers wanted to invest in charter schools as a way to boost student achievement, but at the time there was no high-quality charter school operator that was big enough. So they helped KIPP scale up. But many donors don’t want to spend that kind of time and energy on nurturing an organization.

Prospective donors themselves can contribute to this problem if they so narrowly define their area of interest—by geography and issue— that they end up with few organizations or initiatives on which they can sensibly make a big bet. “Our capital aggregation work is about working with philanthropists to make bigger bets than any of us could do alone,” says Edna McConnell Clark Foundation president and CEO Nancy Roob. “As we’ve increased the ambition of the work, we’ve needed our partners’ help to expand what we’re willing to consider, deepen the thoroughness of our sourcing and due diligence, as well as extend the depth of support we provide—so we could collectively discover opportunities that would lead to even greater impact.”

Even if a social-change organization exists that matches a donor’s interests, a shovel-ready opportunity may not. Well-developed norms and widely understood approaches exist for big gifts to higher education, hospitals, medical research, and the arts: building campaigns, endowed chairs, research centers, and the like. And these large institutions usually have large, highly professional development teams to tailor and market big gift opportunities, using time-tested techniques.

For social-change nonprofits, donors or their agents often have to roll up their sleeves and dive deep into the design of something that can achieve big results and is meaningful. That puts a premium on genuine collaboration between donor and nonprofit—something that is difficult when the balance of power is so much in the donor’s favor. The Edna McConnell Clark Foundation, Good Ventures, and the Sandler Foundation are among donors who regularly manage this dilemma by asking (and often supporting) the leaders of their most promising grantees to develop their own strategic plans for the use of significant new resources.

The lack of personal relationships. Whether in the nonprofit world or in business, significant deals hinge on the personal relationships and trust between the two parties. Almost all major donors talk about the supreme importance of their belief in a nonprofit organization’s leader. For institutional gifts, there is often a built-in personal connection: the donor or a family member went to that university, was a patient at that hospital, or attends concerts or exhibits at that cultural institution. Professional development officers and organizational leaders know how to nurture those relationships into big gifts and how to speak the language of major donors. On the social-change side, there may well be a strong preexisting connection by the prospective donor to the issue—preventing hunger, protecting wildlife, or helping kids succeed in school—but much less often to the organization itself or its leader.

Barbara Picower, who created the JPB Foundation, has spoken about getting to know promising leaders over several years before she bets big on their work. A major supporter of the Harlem Children’s Zone, she recalled meeting its leader, Geoffrey Canada, in a small office, and sharing a lunch of sandwiches and chips, when the organization was still called the Rheedlen Centers for Children and Families.

Not surprisingly, the nonprofit leaders who have most successfully secured big bets have typically found ways to build strong personal and trusted relationships with donors. This is true of the relationship between Canada and legendary investor Stan Druckenmiller (Harlem Children’s Zone’s board chair and anchor donor), as well as for the leaders of Teach for America, KIPP, City Year, and their major donors, to cite just a few examples. And some leaders have found ways not only to build a network of relationships but also to develop an ability to interact with potential donors as peers. Youth Villages, which serves youths in the foster care system, has received multiple big bets from multiple donors. As a young leader, Patrick Lawler, Youth Villages’ CEO, aggressively courted mentors from the business world. He later became the first nonprofit leader inducted into the prestigious Society of Entrepreneurs in Memphis.

The difficulties of measuring social change. With institutional gifts, results are often easy to see: a new wing is completed, a concert hall opens, or the donors get to shake hands with the distinguished professor whose chair they endowed. But defining what a big-bet, social-change gift is supposed to achieve, and then assessing “success,” can be challenging. It often takes years, if not decades, to see a gift’s full effects. Even then, attribution is difficult, given the multitude of factors that contribute to social change. There are some exceptions—nonprofit organizations such as Harlem Children’s Zone and Teach for America—that have invested deeply in measurement. But by and large, social-change results are far murkier.

This inherent uncertainty can be enough to give even the most risk-tolerant donors pause. And it ups the stakes on investing deeply (both time and money) in getting clarity about the ultimate goals and establishing a process for assessing progress. For some donors, having scientifically proven results is a must. But many donors seeking to support social change efforts are willing to compromise, as long as they have a meaningful and audacious goal, with a straightforward and believable way to achieve it, that rests on a relevant track record, coupled with measurable milestones. “We care a great deal about results, and it has taken a lot to get clear on the effects of our poverty-fighting investments,” says Picower. “We have frequently made additional grants above our programmatic ones to support measurement and evaluation of these programs, as we did with the Harlem Children’s Zone’s Healthy Living Initiative.”

Note: To view a larger version of this table, click here.

Mindset Challenges

Philanthropy is as much a communal activity as an individual one. Mindset matters—and mindset in the media, among peers, and by the donors themselves can make it harder to bet big on social change.

More public risk, less public reward.

One of the risks of making a big bet on a social issue is that donors can be subject to negative press if the bet does not meet its goal. Consider the pummeling that Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg took in the aftermath of his $100 million gift to turn the Newark public school system into a “symbol of educational excellence for the whole nation.” Just four years later, media outlets sharply criticized the grant. Business Insider headlined its story “Mark Zuckerberg Gave New Jersey $100 Million to Fix Newark’s Schools, and It Looks Like It Was a Waste,” and a New Yorker article described Zuckerberg as having been “schooled” by his Newark experience. The actual results were more nuanced— the funds brought significant additional dollars into the system and overwhelmingly supported core educational activities (including teacher compensation), and a recent study showed that the city’s charter schools had the second highest gains in student performance of any system in the country2—but the negative verdict on this big bet is likely to be the one that sticks.

In contrast, funding a new building or a faculty chair typically offers nothing but upside among peers and the general public. Naming rights are a frequent benefit that connects a donor’s name to a prestigious institution for generations. Peer esteem flows from the institution’s own promotion of donor contributions. And the annual articles published by major publications about top philanthropists— such as Forbes, the Chronicle of Philanthropy, and Bloomberg—identify the leading donors almost entirely by how much they give, not what they support or whether they make daring big bets on social change.

A higher bar for success.

As the Newark example shows, big bets on social change can be held to a higher standard than big institutional gifts. “The expectations and motivations are simply different,” says Joel Fleishman, who has been one of the leading fundraisers and donors to both higher education and social-change organizations. “Donors expect a level of outcomes from a gift to social change that they simply do not in support of a cherished institution.” One executive director who works for a driven, results-oriented donor mentioned spending many months and dozens of phone calls refining a potential five-figure grant to a promising yet scrappy social-change organization. Yet at the same time as that extremely diligent effort neared completion, a campaign was under way at the donor’s alma mater. After one phone call, the donor decided to make a seven-figure contribution to the campaign. Giving to institutions is important. And high expectations are good. But should gifts to traditional institutions always be risk-free, whereas gifts to social change carry jeopardy?

Underinvestment in securing deals.

We all want philanthropy to fund social change, not underwrite the costs of finding and structuring the deals themselves. Yet this work takes time—either by the donors themselves or their staffs or intermediaries. Donors need to determine what issues are important to them, what leaders they can trust, what organizations or initiatives are most effective, and where their philanthropy can make a critical difference.

In a private equity firm, a partner can do well just by finding one great deal every couple of years. Few donors, institutional or otherwise, invest that much time finding and researching grants to social change organizations. “Serious due diligence is one of the biggest missing ingredients in philanthropy today,” says Herb Sandler, who along with his wife Marion helped launch the nonprofit media organization ProPublica. This problem is particularly profound for philanthropies led by active donors, who often want lean teams but have limited time themselves.

Note: To view a larger version of this table, click Download in the menu at the top of this article.

In an example remarkable for its rarity, Cari Tuna and her husband, Dustin Moskovitz (who in their 20s became the youngest couple ever to sign the Giving Pledge), spent three years meeting with hundreds of people to refine their approach to philanthropy before becoming significant backers (and users) of GiveWell, an organization focused on identifying giving opportunities with the highest impact per dollar. One result of this extensive due diligence process was their $25 million grant to GiveDirectly, a nonprofit that helps people in extreme poverty by giving them unconditional cash transfers.

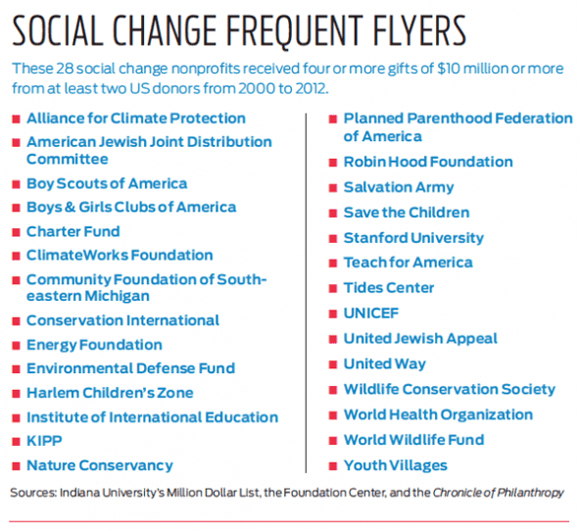

Finding Big-Bet Ready Organizations

Fortunately, increasing the number of donors who make big bets on social change is not dependent on available wealth, willingness to give it away, or desire to support social change. Any of these would be much harder to change. Mindsets around big bets can evolve—the negative social media buzz around some recent huge gifts to universities could be a harbinger of an emerging shift.3 And although breaking through the barriers of finding and structuring deals will require continued bold pioneering by donors and heightened understanding of lessons learned from past big bets, the organizations in our study that dominated our big-bet recipient list suggest some promising avenues to explore. (We consider 28 of the organizations in our study to be “frequent flyers” because they received four or more big bets from at least two different donors during the period of time we studied. See “Social Change Frequent Flyers” below.)

Aggregator intermediaries:

Intermediary organizations that aggregate and re-grant philanthropic funds make up 43 percent of the frequent flyers. Strikingly, although these intermediaries received 23 percent of social-change big-bet dollars, they represent only one percent of institutional large gifts. United Way is a classic example of an aggregator. A newer one is the Robin Hood Foundation, created in 1988 and today New York City’s largest poverty-fighting organization.

Unlike the Fishers, donors who bet big on the Robin Hood Foundation don’t have to conduct an extensive search for an organization that might be capable of using their gift effectively, figure out how a deal might be structured, and create and track metrics that would tell them if their gift was making a difference. This is precisely what Robin Hood does for them. Hedge fund manager Paul Tudor Jones and several partners founded Robin Hood because they wanted to build an organization that would attract significant resources to fight poverty at some level of scale, while also investing in research to find the kind of solutions that might be hard for individual donors to discover on their own. Robin Hood develops long-term strategies to decrease poverty in New York City, finds effective nonprofits and programs, and develops and tracks a set of metrics designed to ensure that philanthropic money goes where it can do the most good in fighting poverty. In 2014, Robin Hood invested $133 million in its poverty-fighting efforts and was able to report evidence of success. For example, 90 percent of formerly homeless participants in the housing programs it funds don’t return to shelters, and the high-quality pre-K programs it supports increase a child’s chances of graduating from high school by 30 percent.

How to Land a Big Bet

Big bets clearly aren’t for every organization; many nonprofits are simply too small to be able to use a large gift effectively. And in most cases, an organization needs to build a track record of results before even considering going after a big bet. But if cultivating one makes sense for your organization, here are some tips to help you succeed.

Working with both big bet donors and recipients has given Bridgespan a distinctive window into how nonprofit leaders can best position their organizations for large grants. Our advice is rooted in good practice for cultivating philanthropic gifts of any size. But when the asks are among the biggest a particular donor has ever given or a grantee has ever received, the stakes go up—way up—and things that may have been optional become absolutes. Topping the list are the following six best practices.

A Relationship Based on Trust

Trust between a donor and a nonprofit leader is almost always the most important currency of a big bet. You need a donor who knows you well and trusts you deeply. Building this type of relationship takes a great deal of time (measured in years, not months).

A Clear Investment Hypothesis

To attract a big bet you need an idea that is clear and compelling, one that seems like an investment that will take the organization to a new level. Would the big bet allow your organization to move from the local to the national level, solve a problem at the scale of the need, or introduce an ambitious new service offering? You’ll also need a clear explanation of how your organization, with philanthropic support, can reach this new level and why it is a compelling “arrival point.” Simpler is almost always better. If the “how” requires a leap of faith or is a double bank shot, it’s unlikely to be appealing.

A “But For” Rationale

The idea should be something that can happen only with the donor’s support. (“But for your gift, we could not do this.”) If it has a good chance of happening anyway or if another donor is better positioned, you will have a harder time making a compelling case.

A Natural Match

There has to be a natural match between what matters to the donor and what’s important for your organization. Donors are unlikely to change what they care about or how they believe change happens in the world. At the same time, the dangers of pulling your organization off mission or away from core strengths are clear, particularly at the scale of a big bet. This places a premium on finding a donor with interests and beliefs that overlap with your organization’s goals and methods.

A Healthy Dose of Co-creation

In almost every big bet we’ve seen, there has been some level of joint exploration between the donor and the grantee. Being able to help shape the deal attracts donors who are looking for defining grantmaking opportunities. That influence can also be advantageous to your organization, allowing you to reap the benefits of the donor’s experience and get her to put greater skin in the game. Of course this requires a delicate balance. The donor can’t have so much say that she dominates the process and draws your organization away from its mission.

Good Housekeeping, Really

Donors want to make big bets only on an organization that is run professionally. They have to believe that you’re not a fly-by-the-seat- of-your-pants operation, but rather someone who will steward their money as well as they have done. This means, for instance, having sound financial reporting, professional- looking materials, a strong board, and a top-notch team.

Sometimes aggregator intermediaries are themselves big bettors, re-granting funds via grants of $10 million or more. In fact, these donors account for 10 percent of the social-change big bets in our database. Take the Edna McConnell Clark Foundation, which in its growth capital aggregation work made gifts that were bigger than any of the individual contributions it received. Other aggregators distribute funds in smaller amounts, yet can still capture the benefits we associate with big bets. The reason, as Robin Hood shows, is that these intermediaries tend to give in a coordinated fashion, thereby channeling large sums coherently in a way that reflects donor intentions.

Social-change fields with institutional characteristics:

Among the frequent flyers, we also see many big bets that bear a striking resemblance to institutional gifts. Some social-change fields more naturally mimic the characteristics that make universities, hospitals, and the arts big-bet magnets. (See “How to Land a Big Bet” below.) The environment is one, with its ready giving vehicles (land gifts), a natural connection with many donors (deep connections to the outdoors that go back to childhood), and measurable results (acres preserved). In fact, a disproportionate number (nearly 30 percent) of the frequent flyers are environmental organizations. TNC was the “most frequent” frequent flyer, with 20 documented big bets over our 12-year study period. Other asset-intensive fields, such as child welfare, are similarly ripe for big bets.

There are also social-change wings within some traditional institutions. Although we have categorized most big gifts to universities as “institutional,” some universities have received multiple big bets specifically focused on ambitious social change. Stanford University stands out: of the 52 big bets it received, four were focused on ambitious social-change purposes—including a gift to fund a new center on urban poverty in the developing world as well as one to create a center focused on restoring and protecting the world’s oceans.

Prior big-bet recipients:

Obviously, one of the best ways to find an organization capable of handling a big bet is to look for those that have already received one. Leaders at the frequent flyers we interviewed consistently told us that landing one big bet is one of the best ways to attract more. In our broader big-bet database, nearly a quarter of the social-change recipients received two or more during the 2000 to 2012 timespan.

Building on Past Successes

Because of its exceptional wealth and generosity, the United States is the world’s largest philanthropic market by an order of magnitude. If donors could close the aspiration gap, billions of additional big-bet dollars would flow to the world’s most challenging problems, and millions of lives could change for the better for generations to come.

But if the social sector is to see more big bets go to the ambitious types of social change that philanthropists aspire to pursue, we need to build on the lessons that pioneering big-bet donors and recipients have learned. Making big bets on social change is genuinely hard. We must provide donors with a greater level of actual support. In parallel, media coverage must also change its focus and tone, to begin to shift the deeply entrenched mindsets that discourage big bets on risky social- change goals towards mindsets that are more like those of Doris and Don Fisher—willing to search for the right investment, willing to envision the long term, and willing to structure an optimal gift for the beneficiary organization(s), with the bigger picture in mind.

Each year for the first six years of the KIPP network that they helped to create, the Fishers visited every new KIPP school. At the time of Don Fisher’s death in 2009, KIPP CEO Richard Barth recalled: “For KIPP staff who have been with KIPP more than a year or two, there is a good chance they actually met Don… . He loved seeing our new schools and was thrilled with the increasing reach of our network.” KIPP and its schools, teachers and students were as tangible to Don and Doris Fisher as any research institute or museum wing.

We need to continue to explore ways to help more donors and nonprofits overcome the barriers that the Fishers and KIPP had to overcome so that they, too, can bet big on social change and see the bet pay off.

Read the related article, “Lessons from the Moore Foundation’s Largest and Longest Grants.”

Notes

1 Ten of the movements we studied received at least one pivotal big bet: spread of 9-1-1; universal health care; legalization of marijuana; Green Revolution; antimalaria; LGBT rights; conservative movement; vaccinations in the developing world; climate change; and civil rights. We did not identify any such bets for the remaining four: Mothers Against Drunk Driving; factory safety; hospice care; and the prevention of female genital mutilation.

2 “Urban Charter School Study: Report on 41 Regions, 2015,” by the Center for Research on Education Outcomes https://urbancharters.stanford.edu/download/Urban%20Charter%20School%20Study%20Report%20on%2041%20Regions.pdf

3 See, for example, Malcom Gladwell’s criticism of John Paulson’s $400 million gift to Harvard University, http://www.cnbc.com/2015/06/03/malcolm-gladwell-slamsjohn-

paulsons-gift-to-harvard.html and this op-ed on the $70 million donation Dr. Dre and Jimmy Iovine made to the University of Southern California, http://articles. latimes.com/2013/may/21/opinion/la-oe-kimbrough-usc-dre-20130521

4 http://www.gatesfoundation.org/Media-Center/Speeches/2015/01/Gavi-Pledging-Conference

William Foster is a partner and head of the consulting practice at The Bridgespan Group. He was previously executive director of the Jacobson Family Foundation.

Gail Perreault is senior director of The Bridgespan Group’s knowledge unit. She was previously director of learning and performance management at the Jacobson Family Foundation.

Alison Powell is philanthropy knowledge manager at The Bridgespan Group. She started her career at The Parthenon Group, a management consultancy.

Chris Addy is a partner in The Bridgespan Group’s Boston office. He was previously a consultant at Bain & Company.

The authors thank Bridgespan colleagues Sam Swartz, Bradley Seeman, Elise Tosun, Sara Glazer, and Tom Tierney for their contributions.

This article appears in the winter 2016 issue of "Stanford Social Innovation Review," published on Nov. 19, 2015.