Eleven-year-old Joey eagerly flipped through the English-Spanish dictionary. He wanted every word to be perfect in the book he was making—a first reader for children in a Guatemalan mountain village. Three weeks earlier he had learned about Guatemala’s Ixil Indians from a guest speaker. The speaker had shown slides from her recent visit to the village and explained how learning Spanish was virtually the only chance Ixil children had to escape the poverty of their tribe. Joey’s Spanish class was making Spanish-language books to help.

As Joey worked on a story about a fisherman, he asked the three other students in his group for advice. “Is this noun’s gender right? Is this the correct verb tense? Have I used all the vocabulary words we were supposed to include?” It was no accident that he was learning exactly what his state board of education’s frameworks for Spanish instruction prescribed. His teacher had used the standards to define the criteria for the book project.

Joey attends an Expeditionary Learning school. Started in 1992, Expeditionary Learning Schools (ELS) guides educators to teach through active pedagogies, with a particular focus on learning expeditions: long-term investigations that are keyed to state academic standards and include individual and group projects, field studies, and presentations of student work to audiences beyond the classroom. Content and skills are taught in the context of projects that have meaning for the students. Children learn because they have a need to know, and they create high-quality products because there is an authentic audience who will benefit from them.

ELS was one of the first comprehensive school reform designs that the New American Schools Development Corporation supported. After just six years in operation, it was hailed by Congress as a national model. Schools from Portland, Maine to Portland, Oregon actively sought to work with ELS. By spring 2004, the organization had contracts with 126 schools, three-quarters of which were traditional public schools with the remainder public charter schools. Over 90 percent had a high percentage of low-income students. All together, almost 40,000 students were attending ELS schools.

Evaluations by seven independent researchers attested to the power of the ELS model: the culture and instructional practices of an ELS school changed for the better; student attendance and parent participation increased; the need for disciplinary actions decreased; and student learning and performance improved. These impressive results caught the attention of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, which made a $12.6M grant to extend ELS’ work with new small high schools in needy areas. ELS’ leadership then teamed up with the Bridgespan Group to develop a business plan to guide that growth in the context of continuing to improve its overall program.

Key Questions

From January through May of 2004, a project team consisting of Expeditionary Learning Schools/Outward Bound’s President and Chief Executive Officer Greg Farrell, Director of the New High Schools Project Jane Heidt, Chief Financial Officer John Clarke, key field directors, and five Bridgespan consultants collaborated on ELS’ business plan. Among the questions they addressed:

- How successful were ELS’ efforts to implement its research-based model with schools?

- If there were schools that were not adopting the model fully, what was getting in the way?

- What steps should ELS take to maximize its impact?

How Well Are We Doing?

Before formulating a growth plan, the ELS-Bridgespan project team needed to get really clear about how well the organization’s current initiatives were working. While ELS’ leadership knew the organization was making progress in almost all of its schools, they were concerned that it wasn’t enough to fulfill ELS’ mission: helping to create a network of good and excellent elementary, middle, and high schools that bring out the best in students, teachers, and administrators.

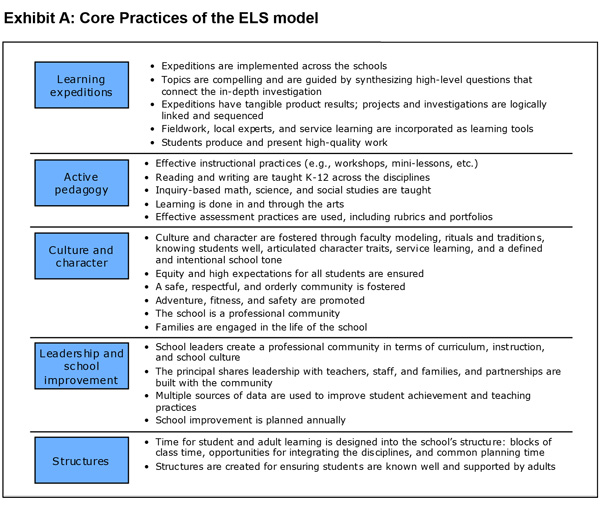

As noted, multiple research studies had shown strong student outcomes when schools implemented the ELS model with fidelity. While the organization had not been able to track student outcomes on an ongoing basis, it had developed a system to track schools’ level of fidelity to the model. Implementation of the ELS model was an imperfect indicator of student outcomes, but it was the best information they had at the time. Excellent schools implemented the model’s “Core Practices” at a very high level and helped lead others to excellence; good schools implemented most of the Core Practices well, but were not yet leaders with respect to the whole design. (Exhibit A lays out ELS’ Core Practices.)

The data challenges were further complicated by the fact that the system for assessing schools’ implementation of the model was quite new. The reviews were intended to monitor the progress of each school against a consistent set of benchmarks tied to ELS’ Core Practices. But this was the first year in which an attempt was being made to review implementation in all schools, and staff still were working out how to use the measures for the dual purposes of assessing the network’s performance as a whole and setting goals on a school-by-school basis. As a result, there were inconsistencies in the ratings. So while the information was useful for creating customized improvement plans, it wasn’t yet reliable enough across schools to allow ELS’ leadership to analyze the network in its entirety.

ELS was on a path to improving the implementation-review data, but the timing would not be fast enough to inform the business-planning project. The ELSBridgespan project team instead conducted its own assessments by interviewing ELS field staff—individuals who worked directly with the schools. The field staff called on their intimate knowledge of the schools and put each one into an implementation category:

- Good/excellent;

- Making strong progress towards being good/excellent;

- Not making strong progress.

The process was iterative, with project team members circling back to the individual field staff members to calibrate the school ratings.

The results were bracing. ELS’ leadership believed they could help their school partners get to the good/excellent level in five years, and sometimes in as little as three years. Eighty percent of the ELS schools that had been active for five or more years or more and 44 percent of schools active three or more years were at the good/excellent level. But many of the schools that had not yet reached good/excellent status were not making the strong and consistent progress necessary to get them there. Moreover, there were roughly 100 schools that had worked with ELS and then ceased active involvement with the organization in the 12 years since its inception.

What Is Getting in the Way?

To decide how to act on this new knowledge, ELS’ leadership needed to develop a better understanding of what was getting in the way of schools implementing the model with fidelity. They believed that moving a low-performing school to good/excellent status took ELS staff working onsite with the school’s leadership and faculty 30 days a year for at least three years. The critical question was: How many of ELS’ schools were receiving this level of support?

Answering this question would take some creativity, since comparable data about the level of services ELS provided to each school were not readily available. The project team dug into ELS’ school contracts and, in a time-consuming but fruitful process, determined the number of onsite days each school was actually receiving.

The bottom line: few schools were as highly engaged as ELS believed they needed to be. Only 20 percent of schools that had started working with ELS between 1998 and 2001 had achieved this intensity over a period of three years or more. Needing to increase school-fee revenue, ELS field staff had been aggressive about signing up new schools. But when a school couldn’t hold up its end of the bargain, ELS staff (still wanting to make a difference with the school and its students) hadn’t wanted to cut it off, so they compromised and worked at a lower level of intensity than the model demanded. In short, there was a disconnect between the way ELS sought to work with schools and what was actually happening on the ground.

Drawing on their experience, ELS’ leadership and field staff identified two main reasons for this disconnect: money and school principal commitment. ELS’ financial model calls for schools to compensate ELS with funds budgeted or granted for professional-development purposes. Many of the lower-performing schools were unable to overcome limited school resources and/or limited school-level budget control. With funds for subsidies in short supply, ELS often worked with them at the level the schools could or would pay, rather than at the more intensive level needed to effect significant change.

Insufficient principal commitment to the program also translated into schools engaging too lightly. The field directors could name numerous principals that had signed on to work with ELS without fully grasping the investment of time and effort required to transform their schools. These principals had gotten more than they bargained for and were not ready, willing, or able to put forth the effort the ELS program required. Principal turnover contributed to this problem. A new principal could quickly shift the school’s structures and energy in a way that wouldn’t allow ELS to be effective. Even the most well-meaning new principals could set schoolwide priorities that blurred the focus of or, worse yet, worked at cross-purposes with ELS’ efforts.

The revelations about the schools’ implementation of the ELS model and the organization’s inconsistent ability to provide schools with the necessary level of support prompted some soul searching on the part of Executive Director Greg Farrell and the board. Was ELS really about helping each and every school it served to attain a specific level of excellence or was it sufficient to help many failing schools improve a little?

Either choice was legitimate in the sense that both helped students. Gaining consensus on this issue was critical, however, because the two aspirations implied very different ways of measuring success, and consequently very different programs. In fact the latter course (pursuing partial improvement where more isn’t possible) would have been easier since ELS was already succeeding quite well on this dimension. After several conversations, however, ELS’ leadership decided to recommit to its existing mission. Helping schools achieve high levels of performance was indeed the real aim. It took good/excellent schools to educate kids the way ELS’ leadership thought they needed to be educated. A small amount of improvement was not enough.

What Do We Have to Change?

The realization had set in: the organization would have to make some major changes if it was to stay true to its mission. In Farrell’s words, “We are hoist on our own petard. If we take our mission seriously, and believe that helping to create a network of good and excellent schools is what we’re about, then a lot of things have to change.” The project team outlined a three-pronged approach to (1) increase fidelity to the model (2) improve its measurement systems (3) invest in its management team and staff.

Increasing Fidelity to the Model

The organization would no longer compromise on the minimum 30 days/year level of onsite support. But with fully 80 percent of ELS’ schools not receiving that level of support, bringing all of them up to the 30-day threshold simultaneously wasn’t an option; ELS simply didn’t have the organizational capacity and funding required. Focusing ELS’ efforts in an impact-maximizing way would mean placing more emphasis on schools that were likely to achieve good/excellent status and pulling back on others.

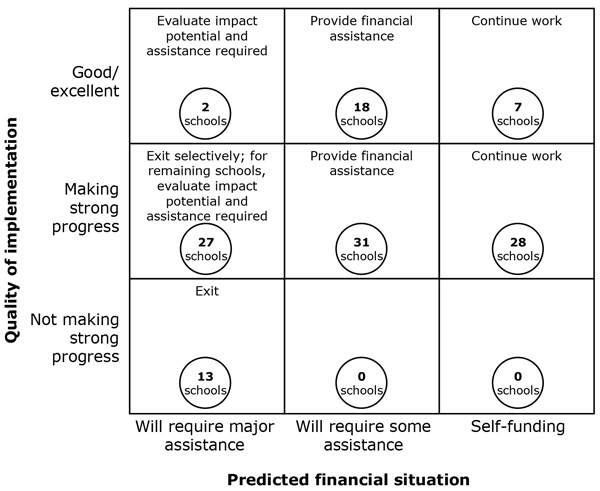

ELS could either work with a small number of schools that required major subsidies or a larger number of schools that needed only modest financial support, if any. Helping more schools appealed to ELS’ management team, especially since there wasn’t a strong correlation between a school’s need for ELS’ services and its ability to pay for them. Accordingly, the field staff divided the schools into three financial categories:

- Likely to line up the funding to pay their own way;

- Likely to require some assistance;

- Likely to require a major subsidy.

The team then plotted this data against the schools’ implementation performance (see Exhibit B). Working cell by cell through the resulting matrix, they clarified the actions required to optimize the ELS school portfolio. For example, the schools in the upper right corner of the matrix—self-funding schools that were good/excellent—were definite schools to continue working with, given their strong implementation and financial performance. Conversely, the 13 schools in the bottom left corner that weren’t making progress and were likely to require major subsidies were clear candidates for exit.

Determining what to do with the remaining schools that would require major financial assistance was tougher. These schools had potential, but the organization didn’t have the financial resources to subsidize them all. ELS’ leadership decided to exit 17 of these schools straight-away (mostly the schools that would not make the commitment ELS required) and to review the other schools in this borderline area in a year to see if they were showing signs of improvement.

Deciding to exit 30 schools was by no means easy. ELS staff cared deeply for the students, teachers, and administrators in these schools. They had worked tirelessly to improve student outcomes and desperately wanted to make a difference. And while they knew that they weren’t getting them to the good/excellent level, they were making incremental improvements in schools that were really failing the kids. “It’s incredibly hard to leave a group of teachers that needs what we offer, even when we know the school as a whole isn’t going to do what it takes,” said Angela Jolliffe, ELS’ Southeastern Region field director.

But even though the idea of leaving these schools was heart-wrenching, they ultimately decided that the alternative of failing to help schools with real potential to achieve good/excellent status was even more unappealing. ELS would use its resources to work with these students, teachers, and administrators even more intensively going forward.

In addition to optimizing its existing network of schools, ELS also would be more systematic about bringing new schools into the network. The project team established a set of rigorous selection criteria for identifying new schools with a high probability of getting to good/excellent. Among the criteria:

- Leadership: The school leadership must be high quality and dedicated to making ELS work.

- Staff: The school staff must understand what is expected of them, including changes in instructional methods, significant time spent on professional development, and a multi-year commitment. Moreover, the faculty must support ELS with enthusiasm, as indicated through faculty votes, interviews, and other means.

- Funding: The school must demonstrate the will and potential to find or dedicate funds to support ELS’ work with them over a sufficient number of years to make the necessary progress.

- School structures: The school must be open to developing structures to support the ELS model, including flexible instructional blocks, teacher teams, and multi-year relationships between teachers and students.

Importantly, these criteria for selecting schools with a high probability of getting to good/excellent would not translate into targeting the best schools. Rather, the criteria were geared toward selecting schools that were willing and able to commit to implementing the ELS model. “Our very purpose is to turn poor schools into good schools, or to create good new schools in places where few good schools exist,” said Jane Heidt, a member of the ELS leadership team. “We’re not choosing any easy school partnerships. We know that Expeditionary Learning practices work well with many students who haven’t done well with traditional approaches, including students with disabilities and English language learners. There’s a history of failure to overcome, so we have to be as sure as we can that our partners have or can develop the capacity to do what’s necessary.”

To give emphasis to the criteria, and to change the nature of the negotiation between ELS and prospective school partners, the project team developed an application that all new schools would complete as part of their initial request to become Expeditionary Learning schools.

Strengthening Measurement Systems

Throughout the business planning process, data had proven critical to developing strategic clarity. ELS’ leadership was committed to having such data going forward, because they could see how critical it was for strengthening implementation across the network. Accordingly, they reinforced their commitment to improving the rigor and reliability of their assessment of schools’ implementation of the ELS Core Practices. By May 2005, each school would receive a consistent “Implementation Review,” so that ELS would have a set of comparable data for all the schools in its network.

Going one step further, ELS also would begin to incorporate student outcomes into the Implementation Reviews. Until now, the organization hadn’t consistently tracked student outcomes or incorporated them into the definition of a good/excellent school. Starting in the 2006-07 school year, the reviews would begin to include student outcomes for schools with a track record long enough to realistically expect improvement. This change was critical to ensuring that a good or excellent school would be defined not only by implementation of the Core Practices, but also by improved results for the kids.

Fortifying the Organization

For the organization to be able to live into these ambitious plans, ELS would have to invest in its management team and staff. The lean organization would need to make hires at both the central management and field levels:

- Marketing director: The responsibility for finding new schools had been dispersed among eight regional field directors, working with only modest coordination, direction, and support from the central office. Given the more rigorous school selection criteria, a marketing director would be needed to improve outreach to schools and to build a pool of committed schools with potential to achieve excellent implementation and the ability to pay for ELS’ services. This person would be responsible for developing and implementing ELS’ marketing, public relations, and communications strategies. The ideal candidate would have experience in setting, managing, and executing marketing strategy, preferably in an education setting. While ELS’ marketing strategy would be set at the central level, the day-to-day outreach to and discussions with potential new schools would continue to be done by field directors.

- School designers: To promote more consistent implementation of the ELS model at a higher level of intensity, ELS would need to hire additional school designers—the individuals who carry out ELS’ day-to-day work within schools. The organization would increase its pool of school designers from 19 to 25 before the start of the 2004-05 school year.

- Director of data programs: The stepped-up measurement initiatives meant creating a director of data programs position. This person would be in charge of making the Implementation Reviews consistent across all schools and systematically incorporating student outcomes into the review process.

- School funding support consultants: To increase the odds that schools could engage with ELS intensively enough to create lasting reform, school funding support consultants would conduct a six-month pilot for ELS, to examine the potential to help schools access different types of government and other available funding sources. The consultants would provide customized, hands-on assistance to selected schools, helping with grant identification and writing. After the pilot, ELS would assess the efficacy of this kind of support and decide whether or not to continue it.

Making Change and Moving Forward

ELS’ commitment to implementing the plan was remarkable. Within one year it had accomplished nearly all of the milestones set forth in the plan: exited 28 of the 30 lowest-performing schools, used more rigorous selection criteria for new schools, signed on 44 new schools, improved the Implementation Review process to be more comparable across the network, hired the requisite staff, and begun to raise a pool of funds to subsidize work with schools that had excellent potential but limited ability to pay for ELS’ services. ELS had also hired two summer MBA interns to help implement the plans: in 2004 to take the marketing strategy to the next level and in 2005 to help them beef up internal forecasting and reporting, so that decisions could be more data-driven.

In June 2005, CEO Greg Farrell reflected on how far ELS had come in the previous year. “We were worried that we might not be able to find schools who would meet our new criteria … [But] the schools we’ve begun to work with in this way have really appreciated the level of rigor and thoughtfulness that we articulated in our model. They’re seeing us as a potential partner in deeply transforming their schools, with a good idea of how hard that will be, but with a great plan to help them get there.”