Why do some organizations succeed year after year, while others are unable to sustain outstanding results for more than a year or two at a time? It’s a simple question that has no simple—or single—answer. But when you look at organizations that consistently better their performance, the explanation might seem to be as easy as the old adage, “success begets success,” because each year’s achievements appear to lead so effortlessly to next year’s even-better results.

In practice, however, the virtuous cycles that drive high performing organizations are anything but effortless. An organization’s success may be fueled by an entrepreneurial leader who attracts talented staff and enthusiastic funders. But it cannot be sustained without good management—the kind of management that involves people throughout the organization in the hard work of clarifying priorities, making tradeoffs and obtaining the resources to deliver results.

Larkin Street Youth Services was in the process of building its organizational capability when they teamed up with Bridgespan in April 2003. Under the leadership of Executive Director Anne Stanton, the agency had developed a nationally recognized model for helping homeless and runaway youth move beyond street life and had achieved amazing results. The momentum to launch new programs was strong, and opportunities to expand their services were many. But with a turbulent economy threatening to constrain funding, Stanton knew that they would have to be extremely thoughtful about plotting their course to sustain Larkin Street’s record of success.

Larkin Street at a Glance

Youth are among the fastest-growing segments of the U.S. homeless population. In 1999 (the most recent year for which reliable data currently exist), some 1.7 million youth under the age of 18 had no home for at least part of the year.[1] Satisfying basic needs like food, clothing, and shelter is a continual struggle for these young people, and many turn to prostitution, drug dealing, and/or theft to survive.

Factor in the circumstances that often cause young people to leave home—physical and sexual abuse, a family member’s drug or alcohol addiction, parental neglect—and you have a population deeply at-risk. Homeless youth are 2-to-10 times more likely than other youth to contract HIV.[2] Anxiety, depression, and low self-esteem also disproportionately affect this population. Their rates of severe depression, conduct disorder, and post-traumatic stress syndrome are as much as three times those of their peers with homes.[3]

For two decades, Larkin Street Youth Services has worked to bring hope to this picture. Initiated in 1984 as a small, neighborhood effort, the San Francisco agency now serves more than 2,000 homeless youth each year. Larkin has established a continuum of services that address the immediate, emergency needs of homeless youth while providing tools necessary for long-term stability and success. The continuum starts with housing, then adds services such as education, job training, case-management, medical care, and mental health and substance abuse treatment, all aligned to work toward Larkin’s ultimate social goal: giving homeless youth the opportunity to exit life on the street for good. In 2002, nearly 80 percent of the youth who enrolled in Larkin’s case-management services exited street life, 83 percent of Larkin HIV-positive youth improved their medical status, and 70 percent of Larkin youth who expressed interest in college enrolled in college or other post-secondary training.

Growth has been a key ingredient in producing these powerful outcomes. From 1992 to 2002, Larkin added 14 new programs in eight new San Francisco locations, and its budget grew at an annual rate of 13 percent. This growth enabled Larkin to attract and retain high-caliber staff (talented individuals committed to improving programs for homeless youth) and to keep innovating—elements critical to its success with homeless youth. In turn, Larkin’s innovative programming and ever-broadening impact attracted funders of all types—government, individual, foundation, and corporate.

In 2003, the organization was just completing the final year of a five-year growth plan. The agency had hit nearly every milestone along the way, and the staff was eager to plan its trajectory for the next five years. Executive Director Anne Stanton shared their enthusiasm, but felt it was important to consider carefully the culture of growth that historically had been so powerful for Larkin. She wondered whether and how this culture could be maintained. With the economic downturn casting a shadow on funding sources, she was finding it harder and harder to raise money for continued program innovation, and she recognized that sustaining Larkin’s aggressive pace of expansion would be challenging. At the same time, she feared that if Larkin stopped innovating, funding for core programs also would erode.

These potential obstacles had not dampened the growth aspirations of the Larkin management team, Board, and staff, however. The more programming they offered and the more lives they touched, the more they saw they could do. In fact, they envisioned a vast range of options for achieving Larkin’s mission. Given this combination of challenges and ambitions, Stanton wondered how best to position Larkin to maintain its healthy cycle of service, innovation and growth. She engaged the Bridgespan Group to help devise a five-year strategic plan to broaden and deepen Larkin’s impact without imperiling the work it already was doing.

Key Questions

In the context of crafting this new strategic growth plan, Larkin Street’s management team and Board along with the Bridgespan Group answered three main questions:

- What was the optimal set of initiatives for Larkin to expand its impact?

- How could Larkin finance all that it wanted and had to do?

- How could Larkin fortify the organization’s leadership to help support these initiatives?

Vetting Larkin’s Growth Options

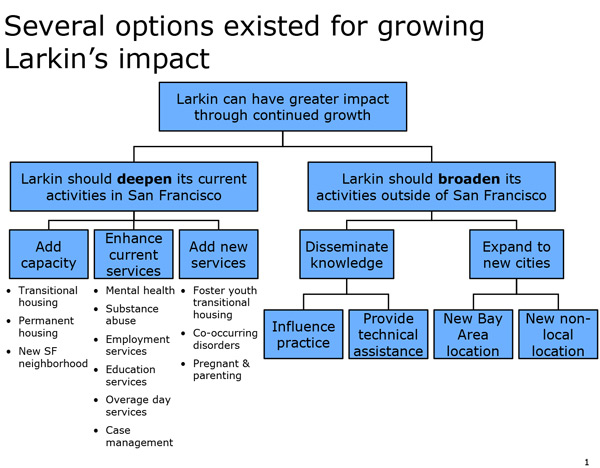

To get all the potential growth initiatives on the table, Bridgespan consultants queried members of the management team and Board. Their ideas fell into two broad categories: (1) deepening Larkin’s current activities in San Francisco, and (2) broadening Larkin’s activities outside of San Francisco (See Figure A: Growth options proposed by Larkin’s management and Board).

While all the ideas had merit, and many reflected the experiences of key stakeholders, there were clearly more options than Larkin could pursue successfully. To prioritize the initiatives that would allow Larkin to accomplish the most good, the project team—comprised of Stanton; Larkin’s Chief Operating Officer, Chief Development Officer, and four Program Directors; and six Bridgespan consultants—devised a two-phase approach. First, they would take four weeks to screen all the options, eliminating those that clearly fell on the bottom of the opportunity spectrum. Then they would spend four weeks investigating each of the remaining items on the short list more thoroughly. In each phase, the project team would use a small number of specific criteria to help eliminate and prioritize growth options.

Figure A: Growth options proposed by Larkin’s management and Board

At the same time, Stanton and the Board engaged in a parallel process designed to clarify the organization’s strategy. Larkin’s mission statement—“to create a continuum of services that inspires youth to move beyond the street”—captured the organization’s reason for being and served as a powerful motivating force, but it wasn’t specific enough to help management and the Board choose among competing options for serving homeless youth.

Creating the Short List

The project team began with the options for strengthening Larkin’s San Francisco presence: adding capacity to current services, enhancing current services, and adding new services (as depicted on the left branch of Figure A). In this first phase, they focused on making sure that each proposal addressed a need that neither Larkin nor another agency was serving. If unmet need for an initiative were low, Larkin would eliminate it from the list.

To gauge the existing need for Larkin’s current programs, the team turned to data that were already in house. Analyzing eight months of occupancy information, for example, revealed that the emergency and transitional housing programs were consistently full (or nearly so), which implied that some kids weren’t getting access. Bolstering these programs constituted a legitimate growth opportunity.

Assessing opportunities to add new services required the team to seek data from external sources. In some cases, relevant data were easy to identify. Statistics from the California Department of Social Services and the San Francisco Department of Human Services, for instance, indicated that programs designed to serve youth leaving foster care presented a bona fide growth option; San Francisco had the highest rate of foster youth in California—19 youth per 1,000, compared with a statewide average of 9 youth per 1,000—and 100 to 175 youth were expected to age out of the system in each of the next several years. Given that already 40 percent of the clients in existing Larkin programs were current or former foster youth, this new data suggested that expanded services dedicated to foster youth could be in order.

Other data were harder to come by, as was the case with the number of youth with both mental health and substance abuse issues (or what is known as “co-occurring disorders”). After uncovering aggregate statistics for homeless people of all ages, which documented high incidence of co-occurring disorders, the team interviewed city officials who reported that homeless youth’s demand for treatment far exceeded supply. Larkin management’s broad expertise then rounded out these data snippets, painting a clear picture of need; youth with co-occurring disorders regularly showed up in Larkin’s programs, so management knew the problem was widespread. In addition, all the existing programs required the young people to find substance abuse care from one agency and mental health care from another rather than to address both issues simultaneously, as the most effective treatment options do.

Last but not least, there were a few options that all the data in the world wouldn’t have helped the project team evaluate. Expanding outside the Bay Area is a prime example. This was where the parallel work the Board was doing to clarify the agency’s strategy proved invaluable. Through intensive discussions and deliberations, informed with data coming from the options evaluation work (the most important of which concerned the magnitude of the unmet needs of homeless youth in the Bay Area), the Board had defined the intended impact for which Larkin would hold itself accountable in the near-to-medium term, namely providing homeless youth ages 12-24 in the Bay Area with the opportunity to exit life on the street permanently. This new strategic clarity, combined with the greater level of difficulty and risk inherent in geographic expansion, led the Board to decide that Larkin would not venture presently beyond San Francisco. This decision made, the team finalized a short list of entirely Bay Area-based initiatives—all aligned with Larkin’s newly clarified strategy.

Investigating the Most Promising Options

With the list of growth options down to a more manageable size, the Larkin/ Bridgespan project team moved to the second phase of the screening process, developing more thorough plans. The team assembled several groups of Larkin staff members, assigning each a set of related growth options to investigate. Senior Larkin directors led staff from across the organization—program directors, case managers, and other line staff—taking full advantage of the variety of experience and perspectives within the organization.

Based on input from Larkin management and prior Bridgespan engagements with nonprofits seeking to prioritize growth initiatives, the team identified three criteria for the groups to use in their assessments:

- “How extensive is the need?” Since all the short-list options addressed unmet needs to some extent, the focus now would be on evaluating the relative level of unmet need each option addressed.

- “Will the initiative build on Larkin’s capabilities and program knowledge?” The reasoning here was that initiatives drawing on Larkin’s competencies would be easier to execute and have a greater chance of success.

- “How strong are the odds that Larkin will be able to secure funding for the initiative?” Given the unsettled state of the economy, Stanton had no interest in risking the good work the agency was already doing by taking on new ventures for which funding would not be assured.

Each group developed program plans for its opportunities, with each plan including: a description of the unmet need the program sought to address and the beneficiaries it would target; an outline of the services the program would include and how those services would address the targeted need; a high-level estimate of the resources required; and a list of potential funding sources.

In preparing the plans, the groups relied heavily on the data collected in the first phase of the screening process. Rather than spending time on more research, they focused on being clear about the specific beneficiaries the program was intended to serve; the impact the program was to achieve for these beneficiaries; and the way in which Larkin would accomplish those results.

They also layered in cost and funding considerations, tapping into their existing program experience to estimate the staff, facilities and other resources the initiatives would require. Larkin’s Chief Financial Officer, who knew Larkin’s cost structure inside and out, then helped the groups translate these resource requirements into rough cost figures. Similarly, to gauge Larkin’s potential for securing funding, the groups turned to Stanton and Larkin’s Chief Development Officer, who were familiar with Larkin’s funders and knowledgeable about what they were likely to support. The Bridgespan team supplemented Larkin’s internal assessments with interviews of current and prospective funders.

The groups presented their plans to a panel of senior program directors at an all-day offsite retreat. In active Q & A sessions, the panelists pushed the groups’ thinking and tested the logic behind the plans—a process that both deepened their own understanding of the plans and allowed the teams to see the value of using data and analysis in making programmatic decisions.

After all the presentations were over, the directors reconvened at Bridgespan’s office. Their goal: to develop a final list of priority initiatives before going home. To facilitate the conversation, simple props—stickers and a poster-sized chart with the growth options listed down the left side and the three criteria listed across the top—proved useful. Ticking through the options one-by-one, each program director placed color-coded stickers labeled “Low,” “Medium,” and “High” on the chart to indicate how well it met each of the criteria, drawing on their own knowledge and beliefs as well as the program plans to make their judgments.

When their stickers for a given growth option failed to match, the directors discussed the reasons for their differing opinions. In some cases, they reached consensus quickly; in other cases, the discussions were longer and more impassioned. One of the most spirited centered on the residential facility for homeless youth with co-occurring disorders. The directors disagreed about which youth, specifically, the facility should serve—those with the most acute problems or the highest functioning cases. They could choose only one, because the treatment program would require a different service model depending on whom it served.

The directors who believed the program should help youth with the most acute disorders pointed to Larkin’s history of working with young people no one else wanted to deal with. They also argued that other San Francisco agencies existed to treat high-functioning individuals (youth and adults) with co-occurring disorders.

Directors on the other side of the argument noted that even though other agencies served high-functioning cases, these programs weren’t specifically targeted for youth and, thus, were less than ideal. High-functioning young people (whose most common mental health challenge is mild depression) often had to interact with adults with severe mental illnesses (such as schizophrenia). The directors feared that this contrast, among others, would deter young people from staying in the existing programs or from seeking future help.

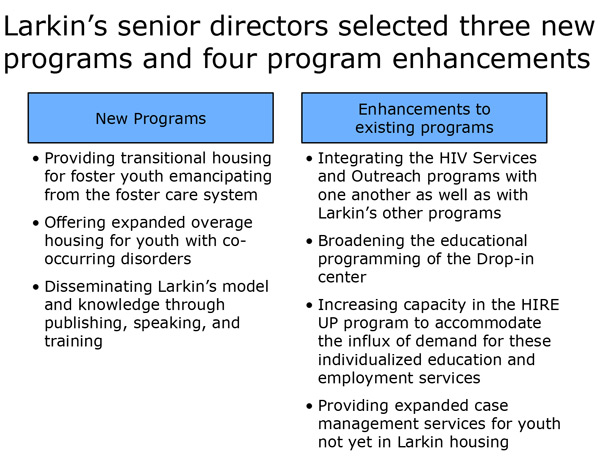

To make this difficult tradeoff, the program directors went back to Larkin’s strategy for impact. The Board had committed to providing homeless youth ages 12-24 in the Bay Area with the opportunity to exit life on the street permanently; that meant independence. In fact, all the agency’s programs were oriented toward this objective. This deep-seated strategy pointed clearly to serving the higher-functioning segment; whereas youth suffering from acute disorders would always require full-time care, these young people had the potential to be self-sufficient once they learned to manage their mental health and substance abuse issues. By the end of the evening, the directors had selected four program enhancements and three new programs for Larkin to undertake in the next five years (See Figure B: New Programs and Program Enhancements). They were exhausted but filled with a great sense of accomplishment. Making tradeoffs between the various initiatives had proven incredibly difficult, but the process gave them confidence that they had identified the set of initiatives that would allow Larkin to do the most good.

Figure B: New Programs and Program Enhancements

The team’s excitement was somewhat restrained, however, as a big hurdle remained—paying for all this growth. How much of this wish list would they be able to fund?

Footing the Bill

The time had come to take an in-depth look at the growth plan’s financial implications. The Larkin/Bridgespan project team attacked this subject from two directions, working on parallel paths to determine: (1) what it would cost to support both the new initiatives and Larkin’s existing programs, and (2) what level of funding Larkin realistically could raise. Doing the cost and funding work separately kept everyone honest—team members weren’t tempted to make the costs fit the revenues they thought Larkin could amass or conversely to get overly ambitious about Larkin’s ability to cover the projected cost base.

Establishing the Cost Baseline

The cost team developed a financial model to estimate the funds required to run Larkin for the next five years. The costs fell into five categories:

- Running existing programs and administrative departments;

- Developing and running new programs;

- Enhancing current programs;

- Investing in Larkin’s infrastructure to support this growth;

- Creating an operating reserve to provide a financial cushion—much needed in these turbulent economic times.

Making basic assumptions about inflation and applying cost-of-living adjustments to salaries and benefits, the team projected that the cost base of their current programs would grow from its 2003 level of $8.7 million to $9.9 million in 2008, or a cumulative increase of $3.1 million over the five years. For new programs and program enhancements, they drew on the plans presented at the offsite, updating them to reflect any subsequent program design changes. New programs, including 21 additional full-time positions, would require $6.0 million spread over the next five years, while the enhancements would add another $1.0 million.

The team also budgeted another $1.3 million to finance the new infrastructure and $1.4 million to build an operating reserve. All in, the cost team projected that Larkin’s yearly operating costs would rise from $8.7 million in 2003 to $12.5 million in 2008. To support this growth, Larkin would have to raise over $12.8 million in additional funding over the next five years.

Focusing the Funding Picture

While the cost team was estimating how much money Larkin would need, a funding team was busy thinking about where the money would come from. They built a separate model with detailed revenue projections. For each source of revenue—government, individual, corporate, and foundation—team members made projections based on historical data as well as the development staff’s estimates of funding prospects.

To guide their work, they established three rules of thumb, born out of experience, values, and savvy management:

- Undertake new residential housing programs only if they could be fully funded, to minimize both Larkin’s exposure to financial risk and the kids’ exposure to the risk of programs ending suddenly;

- Maintain revenue from public sources at less than 65 percent of the revenue mix, to avoid becoming overly dependent on any one source of income and also to allow Larkin to cover overhead costs fully (typically hard to do with government funds);

- Increase discretionary (unrestricted) funding, which in 2003 comprised 18 percent of Larkin’s total revenue, to ensure Larkin would have enough money to continue innovating and to pay for any unexpected expenses.

Abiding by the first rule was easy, because only initiatives with a good chance of securing funding had survived the earlier screening process. However the other two provided significant fiscal discipline, because they put constraints on the sources and uses of funds the team would be able to raise. Mindful of the harsh economic environment, the team also kept projections of future revenue growth on the conservative side.

Balancing the Budget

With both sets of projections complete, the teams compared notes. Based on current assumptions, a substantial gap—$2.1 million—existed between what Larkin wanted to do and what it could afford to do. Determined to make the growth plan workable, they set out to address this disparity, by revisiting the assumptions underlying both the revenue and the cost projections.

On the revenue side, they made only a few minor changes, believing it was both prudent and realistic to keep the assumptions conservative given the challenging economic environment. That left the cost side to shoulder the majority of the changes. Fortunately, wiggle room existed here, because, as Stanton put it, initially they had estimated costs for the new programs and program enhancements with “Cadillac versions” in mind. To close the budget gap, they’d have to trade in for “Honda versions,” making design changes that improved the programs’ economics but didn’t sacrifice outcomes.

And so Larkin directors went through each proposed initiative and eliminated non-essential costs. In the knowledge dissemination program, for example, the directors lowered staffing estimates by 3 full time equivalent employees (FTEs)—a Research Associate, a Training/Curriculum Specialist, and a Peer Advocate—leaving 3.5 FTEs. This staffing model was leaner but still sufficient, they thought, to run the program effectively.

The most dramatic change came in the program for youth with co-occurring disorders. The model initially included in the budget called for a single-site residential treatment center with overnight staff supervision, requiring 10 FTEs. Now, given the financial situation, the directors looked into an alternative model in which the youth would live in a number of rental apartments. The result was a win-win: they found that the scattered-site housing would be more attractive to the youth, require 5 fewer FTEs than a single residence (with 24/7 care), and be better aligned with their program goal of fostering independent living skills.

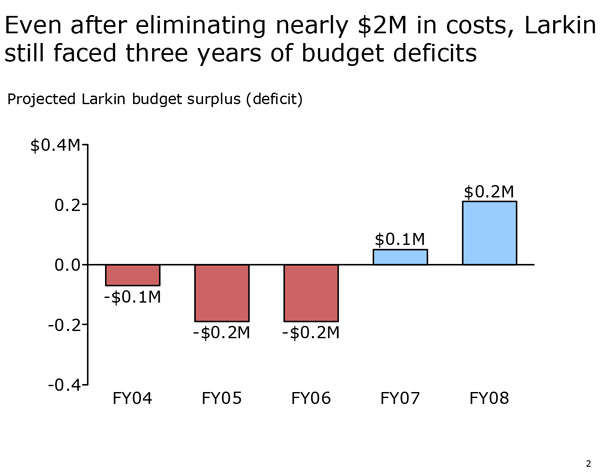

Because all these FTE adjustments also lowered indirect costs (the costs required to provide staff with office space, computers, training and the like), the infrastructure cost projections decreased as well. Ultimately, the directors managed to eliminate $2 million in expenses. They’d narrowed the gap considerably, but it remained at a nontrivial level: $0.2 million. Worse, the projected shortfall would come in the early years of the plan, with Larkin running up nearly a half million-dollar deficit from FY2004 through FY2006 before projected surpluses kicked in (See Figure C: Projected Larkin Budget Gap (FY2004-2008)).

Figure C: Projected Larkin Budget Gap (FY2004-2008)

Refusing to give up, the project team dug more deeply into the reasons for the shortfall. Since the growth plan assumed that program-specific grants would cover both the new initiatives and their share of the new infrastructure, the explanation couldn’t lie in the new programs. That left three other potential causes: the escalating costs of existing programs; the enhancements to existing programs; and the creation of an operating reserve—all of which had to be funded from Larkin’s discretionary revenue. Given the amount of discretionary revenue that Larkin’s development staff had estimated it would be able to raise, however, there simply wasn’t enough to go around.

Just a few options remained for closing the gap, and none of them was a clear winner. They could try to secure additional funding. Or, they could work to scale back one or more of the initiatives that required discretionary revenue, namely: reducing the budgeted salary increases, eliminating or postponing the program enhancements, or lowering the operating reserve. For help choosing among these alternatives, they once again sought guidance from the Board.

Bring on the Board

Stanton convened Larkin’s Board and presented them with the options for closing the funding gap. A number of Board members stated that, given the current economic environment, it seemed disingenuous to revise revenue assumptions upward, so they quickly took the additional funding option off the table.

The discussion then turned to the uses of discretionary revenue, and the Board decided the answer here lay in setting priorities. Several Board members felt that Larkin’s first priority should be to its staff—that undertaking other growth efforts at the expense of keeping salaries competitive would not be fair. These Board members noted that in order to attract and retain high caliber staff, Larkin always had compensated staff fairly.

Other Board members countered that unless Larkin built an operating reserve, the staff itself could be jeopardized—not just the salary increases. These Board members (many of them business leaders) recognized the importance of having sufficient funds set aside as a cushion against unexpected events instead of operating with a zero-based budget as Larkin (like so many other nonprofits) was accustomed to doing. The challenge, of course, lay in finding the funds to set aside, since foundations and government funders are unlikely to put money towards building a nonprofit’s operating reserve. If Larkin were to grow an adequate reserve, targeted at three months of operating expenses, they would have to use unrestricted funding from individuals and corporate donors.

Putting all these considerations together, the Board established Larkin’s priorities for spending discretionary revenue as follows:

- Building an adequate operating reserve;

- Increasing staff compensation at a competitive rate;

- Implementing operational enhancements in current programs.

Based on this prioritization, the project team scaled back the growth plan. They were able to preserve the full operating reserve and staff raises, but had to postpone the program enhancements to bring the budget into balance. Now they just had to ensure Larkin’s leadership was equipped to make all this happen.

Leading Change

Larkin’s plan was realistic but ambitious, putting a premium on continued leadership from the management team and Board. Happily, they were more than up to the task, since the inclusive planned process they had just completed provided considerable hands-on management development.

Developing the Management Team's Capabilities

Evidence of the management team’s more integrated approach to leading the organization quickly appeared. For example, they adopted a new process for prioritizing all their initiatives. Throughout the case engagement, they had drawn on both quantitative and qualitative data as well as their personal beliefs about which growth options made most sense for Larkin given its strategy for impact. In retrospect, this marriage of beliefs and data was absolutely critical to landing on the right set of initiatives. Data proved enlightening and helped them reach consensus, but beliefs also played an essential role—filling in the gaps where data either wasn’t helpful or wasn’t available, and ensuring that they ended up in a place that rang true to Larkin’s mission and values. Devising a workable fund development plan also proved instructive. Key process steps here included separating the cost and revenue analyses and iterating between the fund development plan and the program design process until they reached a workable configuration.

Management also committed to investing in its own operation, to ensure that Larkin would have adequate human resources to achieve its goals. They planned to add four staff members to help handle the extra workload continued growth would bring: an Executive Assistant to the Executive Director, an Associate Executive Director, and an additional staff member in both the Finance and Development departments. These additions to Larkin’s administrative functions were critical, as the organization had added several programs and staff over the years without correspondingly increasing its administrative capacity.

Bolstering the Board

The Board had served as such an invaluable resource during the strategic planning process that Larkin management wanted to ensure that their positive involvement would continue. Articulating clear roles for Larkin’s Board going forward was an important first step in this direction.

The project team was well aware that as Larkin implemented the new growth plan, the demand on Board members for help with fund development activities would escalate. With the help of an outside fundraising expert, the project team established ways that Board members could be involved in the fund development process beyond soliciting donations. Larkin Board members could self-select into one or more of three roles—Advocates, Ambassadors, and Askers—depending on their personal preferences and capabilities. Advocates would promote Larkin’s name in the community. Ambassadors would identify potential donors and help assess their capacity to donate. And Askers would make “the ask” to the people identified by the Advocates. Defining these more nuanced roles would allow Board members who were less comfortable asking people to donate to remain involved in the fund development process.

Additionally, the team identified two Board committees to assist with key fundraising efforts. The Major Gift Committee would help the Chief Development Officer and the Executive Director with the Major Gift Campaign. The Planned Giving Committee would assist the Chief Development Officer in developing and implementing the Planned Giving Campaign. These two committees would provide critical input and lend needed expertise.

Beyond fund development, the transition team also clarified the critical role the Board could play in keeping track of Larkin’s progress against the outcome goals and implementation milestones laid out in the strategic plan. By touching base regularly with the management team, the Board could help ensure that Larkin’s programs were having impact and that the organization was executing the strategic plan effectively.

The final strategic plan included both a plan for programs and a plan for funding. The program plan reiterated Larkin’s commitment to its current programs and described the new initiatives Larkin would undertake over the next five years. It also articulated the resources that would be required—both organizationally and financially—to run the agency. The funding plan described the agency’s funding development goals and strategies and communicated the priorities for Larkin’s discretionary revenue.

Then, just as everything seemed to be falling into place, a new challenge arose. Anne Stanton announced that she would be leaving Larkin Street to become the Program Director for Youth at the James Irvine Foundation. The Foundation had recently revamped its strategy, refocusing most of its grants on preparing low-income youth, ages 14-24, academically for post-secondary education, the workplace, and citizenship, and they were looking for an experienced nonprofit leader to reach youth throughout the state. It was an unparalleled opportunity for Stanton, and the timing was right given that Larkin, with a new plan in the making and a stable financial situation, was as well positioned as an organization could be for a leadership change.

Moving Forward

As of May 2004, Larkin Street is on track with its new growth plan. Perhaps the most significant accomplishment to date has been the successful launch of the foster youth program, with 31 former foster youth already enrolled. Community buzz about the program has been encouraging, capped off by a feature article in the San Francisco Chronicle.

The national search for a new Executive Director is coming to a close and a new ED will be joining Larkin soon. Until then, the senior management team is making all ED related decisions as a group. When they disagree, the team member with responsibility for the area of the decision gets to make the final call. A Board member has taken on the role of checking in with and advising them when necessary.

The benefits to the project extend beyond the tangible milestones plotted in the five-year plan. Larkin’s management team and Board learned lessons along the way that they will continue to apply in the years to come as Larkin faces new sets of challenges and opportunities. Involving the full management team and Board throughout the strategic planning process proved key to developing both a solid five-year plan and the skills necessary to execute on it.

Sources Used for This Article

[1] US Department of Justice (1999)

[2] National Network for Youth (1998) via the National Coalition for the Homeless

[3] Robertson (1989) via the National Coalition for the Homeless