Video: The report's authors describe their research and the opportunities they surfaced for philanthropy to support movements.

Executive Summary

"The scale of hurt that is caused by incarceration is hard to overestimate.”

A question that The Bridgespan Group is increasingly hearing from institutional foundations and high net worth individuals is: when it comes to movement building, is there a place for philanthropy?

The short answer is yes.

For funders interested in criminal justice reform, in particular, movement building is central because it strives to reimagine the criminal legal system and the harm that it causes. That kind of transformative systems change is the very work, as complex as it is, that movements, as complex as they are, are designed to do.

However, movements operate over long timeframes with unpredictable waypoints. So it’s understandable that some funders, even those who recognize the purpose and value in movements, find it difficult to see philanthropy’s role or how different mindsets can support movements more effectively.

To explore these issues we took a deep look into the ecosystem seeking transformative change of the criminal legal system in the United States. Our research included interviews with more than 40 movement leaders, funders, and others, as well as a review of literature, to understand how social movements can achieve equitable change. We also examined the movement behind the 2018 passage of Amendment 4 in Florida, which knocked down the ban on voting for people with felony convictions and marked the single largest addition to the nation’s voting population since the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

Funding Gaps in the Criminal Justice Reform Movement

Large-scale criminal justice philanthropy—funders who think of themselves as tied to these issues in the ways that housing or education funders focus their giving—has come into prominence only in the past five or six years. Its relative infancy means that across the ecosystem many organizations are still very under-resourced. In 2019, the most recent year that complete data is available, funding to criminal justice reform amounted to just $343 million.[1] Compare that to the $2.2 billion bail bonds industry, just one slice of the system that has a strong interest in the status quo.[2]

Bear in mind that many leaders in this space are both those with a criminal record, also known as justice impacted, and people of color. We found the intersection of those identities can be a significant hurdle to securing funding. The struggles faced by justice-impacted leaders were similar to the stories we heard in previous research from leaders of color at large, but amplified because justice-impacted CEOs are often unable to get past the initial hurdle of making connections to the philanthropic community.

As for what areas to fund, we heard repeatedly that there are three critical areas of the criminal justice reform ecosystem that are deeply under-resourced. Funding is especially needed across the South and Midwest where philanthropic resources are lower and criminal justice system challenges more daunting.

- Leadership development: Movement leaders require the resources, knowledge, support, and structure to run successful organizations, as well as the space to develop visions for the future and strategies to get there. Supporting leaders also means creating space for healing and recharging in community with others, which can be critical to movement leaders of color most impacted by the criminal legal system.

- Organizing: Funders more familiar with short-term organizing for political campaigns often underestimate both the number of organizers required to achieve transformative change and the time such mobilization efforts take, which can be decades. The movement ecosystem would benefit from more institutions devoted to training organizers, building a robust pipeline of them, and ensuring they are appropriately compensated.

- Direct advocacy: While significant advocacy work can be supported with 501(c)3 gifts, movement leaders emphasize the need for more 501(c)4 funding, the scarcity of which can be particularly stark for Black-, Indigenous-, and other people of color-led organizations. Norris Henderson, founder of c3 and c4 sibling organizations Voices of the Experienced (VOTE) and Voters Organized To Educate, says simply: “When you attract c4 dollars you don’t just play in the game, you can set the rules for the game.”

Winning Mindsets for Movement Funders

When it comes to movement building, how you fund is as important as what you fund. Philanthropy can play a catalytic role in the transition to a more equitable and just world, starting with the democratization of power, according to our conversations with movement leaders and funders. Power imbalances can be almost blinding when it comes to criminal justice reform movements—where funders and justice-impacted people can exemplify the most extreme definitions of haves and have nots in our society.

The following recommendations are practices funders can use, according to those closest to the work, to better support movement building efforts to transform the criminal legal system:

The Time Is Now to Fund Criminal Justice Reform Movements

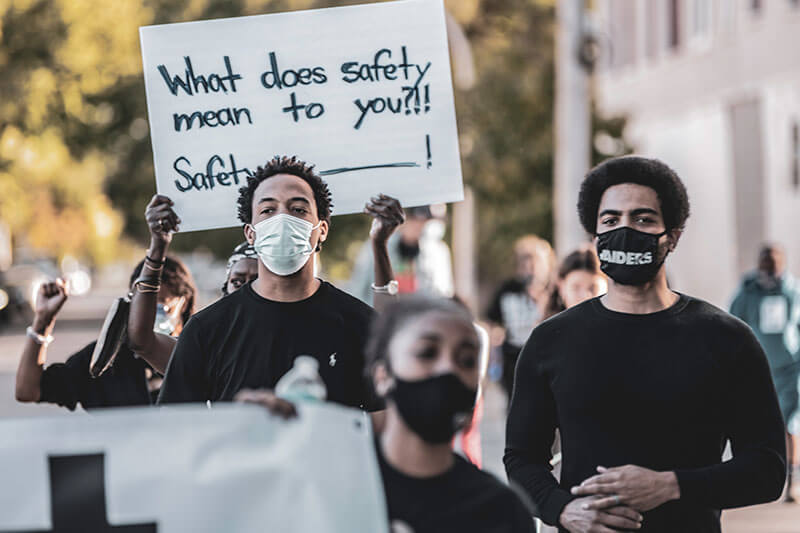

In the months following George Floyd’s murder in 2020, philanthropists promised significant funding to racial equity issues. Not all of it has arrived[3]—and little was directed at the core issues of criminal justice reform that sparked the uprisings in the first place.[4] Compounding the financial shortfall is the need to consolidate progress that has been made. Movements involve challenging power structures, and power structures will inevitably push back. Without defending past victories, the risk is that criminal justice reform ends up worse off than where it started.

In other words, money matters for movements. Philanthropic funding will never be able to start a movement, because people would come together and fight for a better life regardless. But philanthropy is the fuel that gives movements lasting power, can propel them to the next level to achieve transformative success, and sustain them against powerful opposition.

Consider, too, that the work of criminal justice reform is broader than reducing incarceration. It is deeply intertwined with many other issues communities and funders care about, including education, access to housing, employment, economic mobility, health and mental illness, and even climate change. Because of this connectivity, those on the ground working on issues that funders might label as criminal justice often do not see themselves siloed in that way. Movement leaders see their work focused on upending a status quo that jeopardizes our collective humanity and therefore as part of the larger efforts to build a society characterized by equity and justice.

Therefore, we hope this report is helpful for any funder seeking equitable social change. We see a need for philanthropy to invest more resources in transformative change. The need is urgent. The time is now.

Notes

[1] Bridgespan analysis based on Candid data. These are conservative estimates of funding to criminal justice reform related organizations. Some subject areas that may include criminal justice recipients, including legal aid, public interest law, and voter rights, are excluded because the focus of these organizations is not exclusive to criminal justice reform.

[2] IBISWorld, “Bail Bond Services in the US–Market Size 2003–2026.”

[3] Michael McAfee et al., “Moving from Intention to Impact: Funding Racial Equity to Win,” PolicyLink and The Bridgespan Group, July 2021, Malkia Devich Cyril et al., “Mismatched: Philanthropy’s Response to the Call for Racial Justice,” Philanthropic Initiative for Racial Equity, July 2021.

[4] Tracy Jan, Jena McGregor, and Meghan Hoyer, “Corporate America’s $50 Billion Promise,” The Washington Post, August 23, 2021.