Each year Boys & Girls Clubs (BGC), an iconic nonprofit network dating from the 19th century, serves about 4.7 million young people at nearly 4,700 clubs across the United States and on military installations overseas. Seven years ago, the network shifted strategy to help clubs address some of the toughest challenges plaguing America's youth. Dubbed Great Futures, the new strategy redirected the network's primary focus from the number of young people served to the outcomes it could help young people achieve in education, personal health, and character.

Jim Clark, president and CEO of Boys & Girls Clubs of America (BGCA, the network's national office), and his team knew that implementing the Great Futures strategy across thousands of clubs would not be easy. The national office and local clubs would have to retool some of their decades-old delivery models and deeply ingrained ways of working. Clark took responsibility for evolving the national office, knowing it could help the network more effectively implement the new strategy if it found a better way to support its member organizations.1

Great Futures (updated in 2018 and renamed Great Futures 2025) depends on having strong, effective clubs in every community. Yet, data in 2013 showed that club performance varied widely from community to community. Moreover, a number of organizations reported dissatisfaction with the services provided by the national office. "It was clear that the national office needed to become more responsive, more innovative, and much better able to help some individual organizations develop into high-performing operations," said Clark.

This tension between what a nonprofit network wants to achieve and its day-to-day operations isn't unique to the BGC network.2 Increasingly, national and global network organizations have declared ambitious new goals in a quest to evolve from simply serving community needs to also solving underlying social problems, a trend Bridgespan detailed in "Network Transformation: Can Big Nonprofits Achieve Big Results?"3 While these networks have a clear picture of what they want to achieve, they often discover a gap between their new strategy and their ability to follow through. Many are simply not organized in a way to deliver effectively on their updated goals. As BGC discovered, networks that find themselves in this situation need to revamp their operating model, the blueprint for how to organize and deploy people and resources to translate strategy into results.

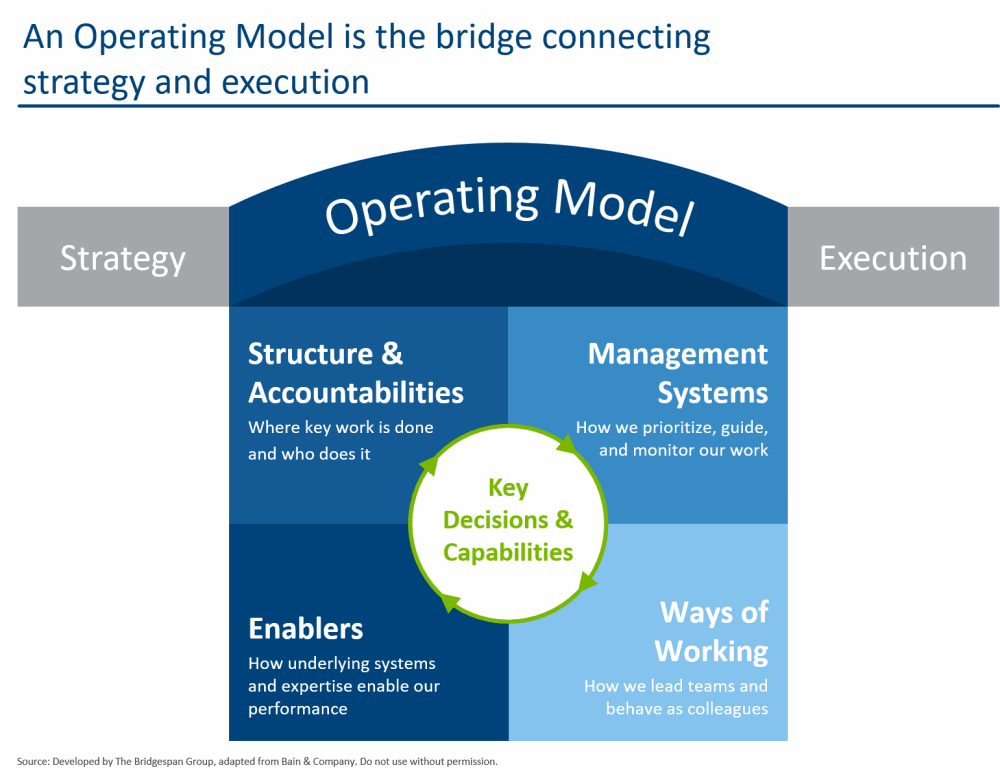

The operating model concept took root in the business world roughly a decade ago and now figures routinely in companies' strategy-execution discussions. Over the last several years, The Bridgespan Group has teamed up with Bain & Company to adapt their business-oriented operating model approach to nonprofits, including networks.4 A recent Bridgespan article based on that collaboration, "Operating Models: How Nonprofits Get from Strategy to Results," describes the four interrelated elements of nonprofit operating models: structure and accountabilities, management systems, ways of working, and enablers that support key capabilities and optimize performance (e.g., talent recruitment and development processes, data and technology, expertise, and learning and innovation practices).5 In essence, operating models define how work is done, who does it, how it is managed, and how people in the organization interact in service of implementing a strategy. An effective operating model is tailored to support the organization's key decisions and capabilities—those that are necessary for the strategy to succeed (see below).

All nonprofit operating models take shape around these four elements, but no two models are alike. That's because no two nonprofits—even if they seek to address similar issues—have the same set of decisions and capabilities that they "must-get-right" in order to advance the mission. For a network, for example, key decisions may include how best to allocate resources across all affiliates. Key capabilities may include effective program development and delivery, or strong fundraising at national and local levels.

The benefits of investing in revamping an operating model justify the effort. Bain & Company research spanning eight industries and 21 countries found that companies rated in the top-quartile of operating model performance have five-year revenue growth and operating margins significantly higher than for those in the bottom quartile. "These high-performing companies have set up their operating models so that organizational structure, accountabilities, governance, and employee behaviors, along with the right people, processes and technology, all work together to support the strategic priorities," wrote Bain consultants Marcia Blenko, Eric Garton, and Ludovica Mottura in a 2014 article.6 Nonprofits can expect similar results in performance and impact if they develop high‑performing operating models.

In our experience, however, many nonprofits take a piecemeal approach to addressing perceived operational shortcomings. They may initiate one-off improvements in recruitment, employee training, decision-making processes, or governance without clarity on whether such fixes address root causes of operating model shortcomings. A Bridgespan survey of national and local staff from 25 US-based nonprofit networks sheds light on the reason for this lack of clarity. Only about half of the respondents said their network spends enough time and resources working on their operating model, compared to 80 percent when it comes to network strategy. And what investments they do make in attempting to improve their operating models are often disappointing. Only 10 percent deemed such efforts "highly effective."

In our work with dozens of nonprofits and NGOs, we have identified eight best practices to guide those seeking to make operating model changes, whether a full overhaul or a partial realignment (see "Tips for Successful Operating Model Redesign" ). These practices apply to any nonprofit or NGO. Networks, however, face unique challenges that stem from their size and complexity. US networks, the focus of our research, share four characteristics that complicate their efforts to address operating model redesign.

1. Activities at three distinct levels—local, national, and network-wide

US networks operate in a particularly complex way compared to stand-alone nonprofits. That's because networks must coordinate and align three distinct levels of activity: local affiliates (also sometimes known as members, affiliates, organizations, chapters, or sites) control their own activities and operations, reflecting community needs that vary from location to location; the national office performs an altogether different set of activities that are primarily in support of affiliates; and the overall network must coordinate a set of unifying activities that, among other things, determine how the network is governed, network-wide decisions are made, and resources are distributed. All levels—local, national, and network-wide—need to work well autonomously and in concert. This three-tiered model complicates the work of network operating model redesign and is often a contributing factor when improvement efforts do not yield desired results.

2. Tremendous diversity within the network

The wide variation among affiliates within the same network is just as important as multilayered structure. Affiliates within a network often vary greatly by the number of people they serve, size of budget, demographics, and geographic location. A single network, for example, may have a set of affiliates with only a few employees and small budgets, and another set with hundreds of employees and multimillion-dollar budgets. That same network may also have affiliates in cities, rural communities, Native American lands, or military installations. This complexity is exacerbated in networks that, like BGC, have hundreds or thousands of affiliates across the country. Addressing the needs of affiliates with such widely divergent programmatic scopes, sizes, and constituencies means that networks can't take a one-size-fits-all approach to operating model design.

3. The balance of local autonomy and network-wide goals

Balancing local autonomy with a network's desire for programmatic scale and efficiency is a well-known challenge for networks. "The network needs to strike a balance between the need for efficiency, national best practices, and local accountability with the need for the folks on the ground to innovate and customize their way of operating," explained Evan McKittrick, former chief of staff for the Boys & Girls Clubs of King County (Seattle). Such a dynamic highlights the fact that what works well for one affiliate may not for another.

"The network needs to strike a balance between the need for efficiency, national best practices, and local accountability with the need for the folks on the ground to innovate and customize their way of operating"

In federated networks where affiliates have high levels of autonomy (whether independent affiliates or centrally controlled by a national office) change is about influence rather than command-and-control from the top. "The trick is, how do we get 900 independent 501(c) (3)s under the same banner to work collectively and more effectively together?" said Y-USA CEO Kevin Washington. (Y-USA is the national office of the YMCA network, which has more than 800 independent affiliates operating in 2,700-plus locations.) "There's a level of independence that each Y has as an autonomous 501(c) (3), but there's also a significant level of interdependence. Everyone, from the smallest Y in Pennsylvania to the largest in California, needs to understand how changes at the federation level benefit each and every one of them in order to get on board."7

Balance also is an issue with centrally controlled networks. While the national office could unilaterally try to direct change, that approach typically fails. Regardless of legal structure or governance model—federated or centrally controlled—network leaders understand that distributed power can slow the pace of operating model change.

4. Long histories and deeply ingrained organizational cultures

Many nonprofit networks have operated in much the same way for years, if not decades. "You just have all of this weight of 100-plus years of how we've done things," said Neil Nicoll, former president and CEO of Y-USA. "My grandfather was board chairman of this YMCA. My father was board chairman of this YMCA, and by God, I’m going to be board chairman of this YMCA. It’s our YMCA.'"8

More than a few network leaders have emphasized to us that this historical legacy and strong culture can be an asset—inspiring a sense of mission and an idea of the network as a movement. At the same time, it can translate to latent (or overt) resistance to the sort of change often required while updating an operating model. As networks make major strategic pivots to focus on solving social problems, their leaders are realizing that they need to invest significant time and resources in designing how their networks may need to evolve to deliver on ambitious new goals. Said the leader of one national nonprofit network: "Our way of operating does not align with our (new) strategy."

BGC Takes on Operating Model Redesign

BGC's experience in dealing with this complexity while undertaking an operating model redesign is instructive. What started as a strategy shift in 2012 developed into a multiyear, iterative process to evolve BGC's operating model at all three levels: local affiliates (organizations), the national office, and the network overall. While BGC did not conduct a comprehensive diagnostic at the outset, it gathered and analyzed data to identify major pain points and demonstrated a willingness to tackle those issues across the operating model.

To that end, President and CEO Clark and his team took the first step when they launched Project Fast Forward in order to transform the national office into a center of trusted, personalized support for every organization in the network. The team set out to shift the mentality at the national office to one in which it viewed its role as completely in service of local clubs in their efforts to impact youth in their communities. Many affiliate leaders collaborated with the national team to chart recommended changes. "We needed to put our clubs first and make sure that everything we do is in the interest of helping those organizations reach their potential. That is, after all, our reason for being here," explained Clark.

"We needed to put our clubs first and make sure that everything we do is in the interest of helping those organizations reach their potential. That is, after all, our reason for being here."

For instance, Fast Forward restructured the role of BGCA's regional service directors, naming them Directors of Organizational Development. The change in title came with new job requirements to ensure that directors had the organizational development skills needed to serve affiliates more effectively. Historically, regional directors often served portfolios of 30 to 40 organizations, which often included responsibility for supporting hundreds of individual club sites. Often these portfolios bundled diverse affiliates, such as very large and very small clubs. As a result, regional directors lacked the time needed to develop deeper expertise in supporting any particular type of club.

Fast Forward doubled the number of Directors of Organizational Development and cut the number of clubs in a director's portfolios roughly in half. It also regrouped clubs by type, such as large clubs in major cities, those that serve Native American youth, and those located on military installations, which gave directors more time to develop deeper knowledge and provide more customized support. The new groupings also led to creation of an "emerging markets unit" that specifically focuses on providing intensive, turnaroundlike support to clubs that are facing significant challenges in delivering on the mission and sustaining their operations.

The national office also set out to help clubs address one of their most vexing local operating model issues: a dearth of high-performing leaders. First it had to address the alarmingly high turnover rate among new club CEOs: 40 percent left within a single year on the job, and 70 percent left within two years. Clearly, the network faced a major challenge with recruitment, development, and retention of its most senior people, a core capability of the local operating model. "This churn was a major impediment to achieving our strategic goals," said Lorraine Orr, BGCA's chief operations officer.

Thus, the national office, working closely with local affiliates, made a significant investment in training for existing club leaders across the network. It has also upgraded the process of recruiting, training, and integrating local CEOs into the network—transforming what had essentially been a one-day onboarding event into an intensive 18-month training process.

Planning and executing these two major operating model changes played out over several years and exposed the need to upgrade network-wide decision-making processes, another common operating model issue for networks. Network leaders recognized that slow network-wide decision making on virtually any topic, big or little, resulted from a cultural preference for consensus. Many thought the slowness was dictated by process requirements in the network's bylaws. But BGC's governing documents enabled networkwide decisions to be made quickly (usually within 60 days). Nonetheless, consensus became the decision-making style, which meant lots of calls, webinars, conferences, and meetings that could drag out the decision process for 18–24 months even for relatively noncontroversial topics.

To address this problem, local and national leaders embarked on an effort to identify key decisions and assess how they should be made, communicated, and implemented. They also recognized the need to better engage local boards in decision making, which had not been happening consistently.

Clark acknowledges that the network's evolution, in particular at its center, has not been easy. For example, in the months following the launch of Project Fast Forward, turnover rates at the national office rose as staff members wrestled with the scope of the change effort and reflected on whether they wished to continue with the organization given the evolution. Even among those teams that supported the changes, it has taken time and patience to learn, adjust, and see changes through. Moreover, the long-term commitment to getting change right can create a sense of fatigue throughout the network.

The portfolios assigned to Directors of Organizational Development are a case in point. Although directors now work with fewer clubs, the numbers still stretch their ability to deliver desired service. Clark says directors' workloads needs to shrink even further so that each club can receive even more personal and specialized attention from the national office. This has gone more slowly than desired because recruiting numerous directors with the right development skills and experience also has proven to be a challenge.

Nonetheless, BGC's efforts, while ongoing, have already resulted in some clear and measurable gains for the network. The network has seen encouraging growth in a key outcome measure: average daily youth attendance. The network also has seen other encouraging indicators including the reversal of a 10-year decline in teen participation.

The number of clubs has grown 14 percent since 2012. Operating revenue, now at roughly $2.2 billion annually, has grown in recent years. Club satisfaction with national office support, a major friction point in the past, has improved significantly. A recent survey found that more than 80 percent are satisfied with the support received from the network's national office, double the 2012 percentage. Moreover, the new onboarding approach for club CEOs cut the turnover rate for individuals in their first year to 10 percent from a historic high of 40 percent.

Is Your Network in Need of an Operating Model Renovation?

For many networks, we believe the answer is yes. The trend among networks to evolve from serving community needs to also solving underlying social problems creates pressure to rethink how a network operates. Strategy shifts of this magnitude typically require new capabilities, roles, ways of working, and adjustments to resource allocation priorities and processes, among other changes. This is the situation that many nonprofit networks find themselves in today.

Even for networks that have not committed to a strategy shift, revisiting one's operating model may still be a necessary investment if there are sustained organizational dysfunctions, such as cumbersome decision making, high turnover, lack of trust, or capability gaps. Our survey data show that a majority of network leaders understand that they need to fix at least some elements of their operating model. Even so, they acknowledge not spending enough time doing so, nor are they satisfied with the results from the attempted changes.

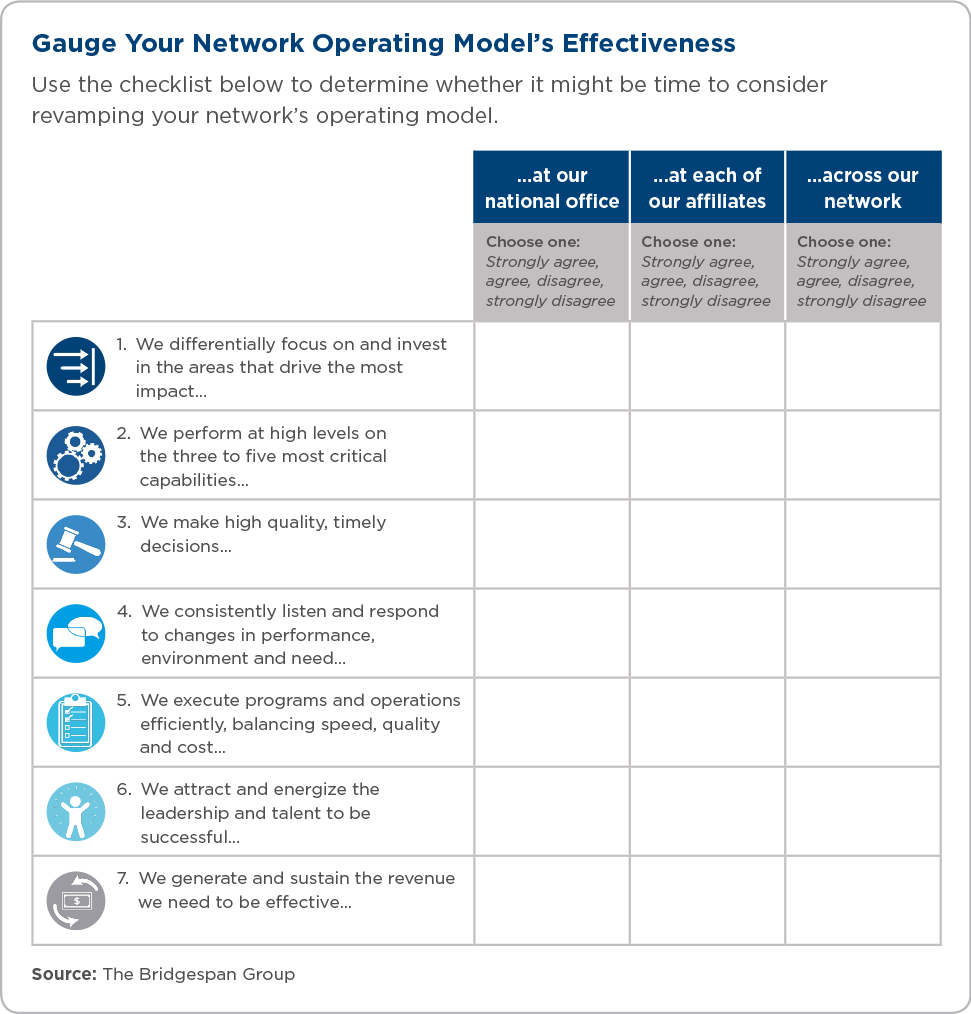

If any of this sounds familiar, consider examining your operating model and its alignment with your strategy. Take time to engage the leadership team in frank conversation to explore how well your network's current operating model is working at the local, national, and network-wide level.

As a first step in this process, we recommend completing the table below for your network. It asks you to take stock of each level of your network on seven statements. While not a definitive diagnostic, it can quickly help you determine whether the time may be right for an operating model revamp and if so, what your network's most likely pain points may be.

Click image to download the chart

Click image to download the chart

While a substantial undertaking, revamping a network's operating model can position it for the next major leap in impact. BGC has been adapting elements of its operating model for nearly seven years (with some pauses along the way to observe and adjust). Throughout the process, leaders realized that "we grossly underestimated in some areas what it was going to take," conceded Clark. But the results have been sufficiently encouraging for BGC to go forward with Great Futures 2025, extending its commitment to strengthening affiliates and creating the best possible club experience for young people. Clark expressed optimism about the outcome: "What we are doing basically lays a foundation for the next 50 years."

Tips for Successful Operating Model Redesign

In Bridgespan's advisory role, we have helped a number of nonprofit organizations—including several networks—grapple with the tough questions that arise from revising an operating model. From these engagements, we have identified eight best practices.

1. Start with strategic clarity.

It is impossible to improve performance without strategic clarity. Redesigning an operating model begins here. Ensure the strategy is specific enough to know what you are designing for: Which lines of business, programs, funding models, and geographies will be the focus? What will it take to succeed?

2. Use design parameters to define what matters most.

Once you are clear about strategy, translate that strategy into a list of requirements for operating model design. We call these "design parameters"—a set of 10–15 written statements that describe what the operating model needs to do to enable the strategy. These parameters essentially serve as criteria for evaluating operating model design alternatives.

3. Up your game on decision effectiveness.

An organization's ability to execute well rests on its ability to make and implement the decisions that matter most. An effective operating model must explicitly address the decision challenges that many nonprofits struggle with: unclear priorities, ambiguous decision roles, poor decision behaviors and meeting norms, and organizational structures that complicate rather than simplify decision accountability.

4. Prioritize must-deliver capabilities over those that can be "good enough."

Prioritize the handful of capabilities most essential to delivering your strategic goals and ensure your operating model is set up to deliver them well. That's why we include "must-getright" capabilities—as well as key decisions—in the center of our operating model framework.

5. Look past structure.

Organizational chart reshuffling is a go-to fix for many organizations trying to do something new or solve for underperformance. While structure is an important part of an operating model, it alone rarely holds the key for delivering on an organization's strategy.

6. Look both within and outside for inspiration.

Nobody knows the strengths and weaknesses of an organization's operating model as well as its employees. Capturing and synthesizing that knowledge can provide a meaningful base for operating model design. In addition, an external look at analogous organizations can spark new thinking and expand design options.

7. Work with a small group before going organization-wide.

Operating model assessment and design can be a complex process. Start with a small group of leaders—the executive team or a core working team that brings organization-wide perspective—that can safely learn, debate, and experiment before refining a high-level blueprint with a wider group of stakeholders.

8. Actively manage the long tail of the change.

Some aspects of an operating model blueprint can be implemented right away. Others, such as new processes or new roles, may require additional design work, ideally led by those closest to where the change is needed. Essential new behaviors can take time to embed. Such complex change requires a well-managed approach that sequences implementation, provides timely internal communications, and ensures sustained leadership commitment.

The authors thank Ben Strauss, Phil Dearing, and Jordana Fremed for their contributions to this article's research, as well as Marcia Blenko of Bain & Company and Bridgespan Partner Leslie MacKrell for their thought partnership. We also thank Bradley Seeman and Roger Thompson for their editorial contributions.