Introduction

In 2021, almost 100 years after local government officials in southern California seized the beachfront land of a Black couple to placate white neighbors complaining about a “Negro invasion,” the tide shifted. Ownership of Bruce’s Beach, once home to the couple’s thriving resort for Black beachgoers, was transferred back to the Bruce family.

More on Reparations and Building a Culture of Racial Repair

In their work, The Bridgespan Group and Liberation Ventures brought together leaders from across the field to create a number of resources for philanthropy to learn from and be inspired by.

- A Reparations Roadmap for Philanthropy: A companion piece to Bridgespan and Liberation Venture's "Philanthropy's Role in Reparations and Building a Culture of Racial Repair," this Stanford Social Innovation Review article explores three key roles for philanthropy in building a more equitable future.

- An Invitation from Aria Florant, Co-Founder and CEO, Liberation Ventures

- What do you see on the "other side" of reparations? Black leaders share their hopes for a more equitable world.

- Reparations Movement Profiles: Four examples of the reparations movement in action.

- Special Collection on Racial Repair and Reparations —And What Philanthropy Can Do: This PDF comprises the entire collection of articles, movement profiles, and inspiration from our research.

It meant that descendants of Willa and Charles Bruce were finally able to claim their inheritance.

“It is never too late to right a wrong,” Janice Hahn, chair of the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors told the press at the time. “Bruce’s Beach was taken nearly a century ago, but it was an injustice inflicted upon not just Willa and Charles Bruce but generations of their descendants who would, almost certainly, be millionaires today if they had been allowed to keep their beachfront property.”1

Today in the United States, if the wealth of white households remained stagnant, it would take Black families 228 years to catch up. That is more than 10 generations.2

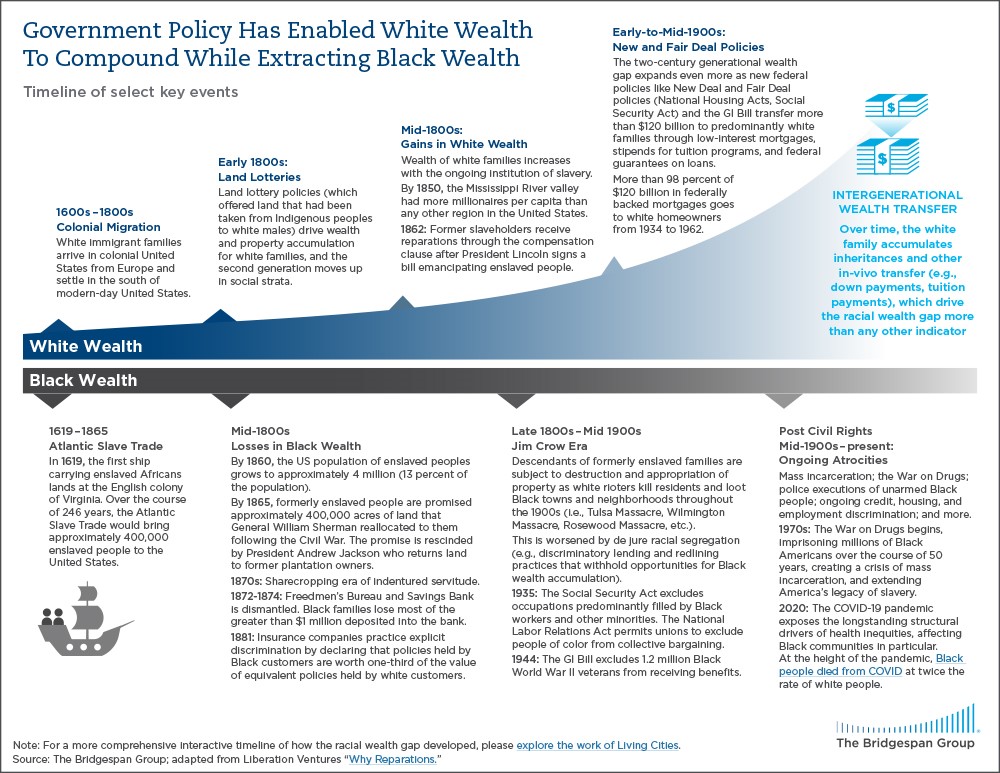

Make no mistake: That gap is not the result of individual “bad” choices or biased myths that some groups are more hardworking than others. Instead, it is the result of what one historian dubs “hard histories”—a pattern of race-based policies, fueled and sustained by anti-Black narratives, that have repeatedly benefited white people while systemically demolishing the wealth and humanity of Black people like the Bruce family. On the policy front, that includes a hundred years of Jim Crow laws; the National Housing Act and redlining; Social Security’s exclusion of the majority of Black people for about two decades; and the GI Bill, which, in practice, also excluded nearly two million Black veterans3—all in addition to more than two centuries of enslavement. (See timeline.) That American history of anti-Blackness and discrimination helps explain why Where Is My Land, the organization created by Kavon Ward, a lead organizer in the return of Bruce’s Beach, currently has a waiting list of more than 700 Black families with compelling claims for stolen land and lost wealth.

What could a different future for America look like?

Imagine if there were no more American stories framed by such gaps, disparities, and inequities.

Imagine an America that refuses to avert its gaze from the harms caused by systemic racism and instead collectively leans into the hard work of repair and transformation, even if all its benefits may not be seen in this lifetime.

Imagine an America where the fullness of Black creativity, ingenuity, and potential is finally revealed.

Currently, there is a broad ecosystem of grassroots organizations, nonprofits, artists, scholars, multiracial coalitions, leaders of color, and, yes, philanthropists, foundations, and other funders working across the United States who see reparations for Black people and creating a culture of racial repair as the missing piece to get to that better world, for everyone.

“When we ask for donors to support reparations, we are not begging for money for Black people. We’re extending a lifeline into your humanity, into your liberation and freedom, by being a part of this healing journey and process,” says Edgar Villanueva, founder and CEO of the Decolonizing Wealth Project. “When we work to repair as a nation—including ensuring Black folks achieve reparations—we are all going to benefit tremendously, and there are going to be generational impacts.”

Reparations Are About the Future

For this article, we define reparations as a comprehensive federal program that addresses the legacy of slavery and the centuries of documented race-based policies thereafter. Inextricably linked to achieving this is building and sustaining a culture of racial repair. (More on this below.)

One of the big misconceptions about reparations is that it is a discussion stuck in the past—only about history long ago rather than an investment, perhaps the investment, in the future. Reparations and the repair that comes with it are an opening, an invitation, and an opportunity to transform ourselves, our communities, and our nation.

“When we think about reparations, it is not just paying for past harm. These harms are happening today and will continue to happen if we don’t do something about it,” says Ward. “This is not just a fight for the now, this is a fight for the future, too. I don’t want to pass this fight on to my child, and I don’t want my child to have to pass it on to her child.”

Because of that opportunity for transformation, Liberation Ventures, a reparations field catalyst and intermediary working to accelerate the Black-led movement for racial repair, and The Bridgespan Group, a global nonprofit that advises mission-driven organizations and philanthropists, came together to explore the role philanthropy could play in the movement for reparations and racial repair as a pathway toward a more equitable future. (Although Bridgespan has engaged deeply for more than six years in the work of its racial equity journey, both internally as an organization and externally in our work, it is, admittedly, still in the beginning stages of employing an explicit reparative lens.) For this research, we interviewed more than 45 movement leaders, scholars, and funders, conducted a literature review, and surveyed senior philanthropic leaders, with respondents representing more than $12 billion in assets.

For funders who believe in racial equity and aspire to a thriving multiracial democracy, we invite you to see reparations for Black people and building a culture of repair as a necessity to reach that goal. Join us in learning from those who are leading the way.

The Racial Wealth Gap and the Opportunity for Transformation

Because of America’s history of race-based policy designed to build white wealth at the expense of Black wealth, many funders, as well as some movement leaders and scholars, come to the work of reparations through an interest in addressing the racial wealth gap. The Black-white wealth gap is $11.2 trillion.4 Closing it would add between $1 trillion and $1.5 trillion in GDP to the US economy. By 2050, if we eliminated additional racial disparities in health, incarceration, and employment, the nation would gain $8 trillion in GDP.5 There is a $330 billion disparity in wealth flow between white and Black families every year, and intergenerational wealth transfer drives 60 percent of that disparity. That helps to explain how the disparity in inheritances between Black recipients and their white counterparts is $200 billion—each year6—and how the nation’s inequities are further reinforced across generations.

Economist William “Sandy” Darity of Duke University, who has researched the racial wealth gap for decades, has long insisted that because of the size of the gap and the race-based national policies that created and sustained it, a federal reparations program is the only way to close it. “My response to philanthropists who resist this idea [of reparations] is, whatever else is proposed, by indirect or universal strategies, is not going to do it,” says Darity. “If you’re serious about closing the racial wealth gap, you have to think about direct mechanisms to get it done.”

The United States is in the midst of the largest wealth transfer in its history. As the baby boomer generation passes away, an estimated $84 trillion will be passed down to heirs, with some $16 trillion transferred in the next decade alone.7 To put that in perspective, that wealth transfer over the next 10 years is 43 percent more than what it would take to eliminate the entire Black-white wealth gap. Because of the history of race-based policy and segregation in the United States, the boomers who benefited most from decades of wealth building were primarily white.8 Rather than reinforcing the nation’s inequity, this immense wealth transfer is a tremendous opportunity to do things differently. Philanthropy could leverage it to create a new path, diverging from the one America has inherited, by seizing the potential that building a culture of racial repair can bring.

Reparations Are an Overdue Paycheck and Build a

Culture of Repair

What’s in a word? A lot, actually. One of the challenges of the reparations movement today is a lack of understanding of what reparations truly means—its required combination of restitution and repair.

Reparations are an internationally recognized legal framework for people who have suffered violations of human rights or humanitarian law.9 When applied to the history of Black people in the United States, we define reparations as a comprehensive federal program that addresses the legacy of slavery and the centuries of documented race-based policies thereafter.

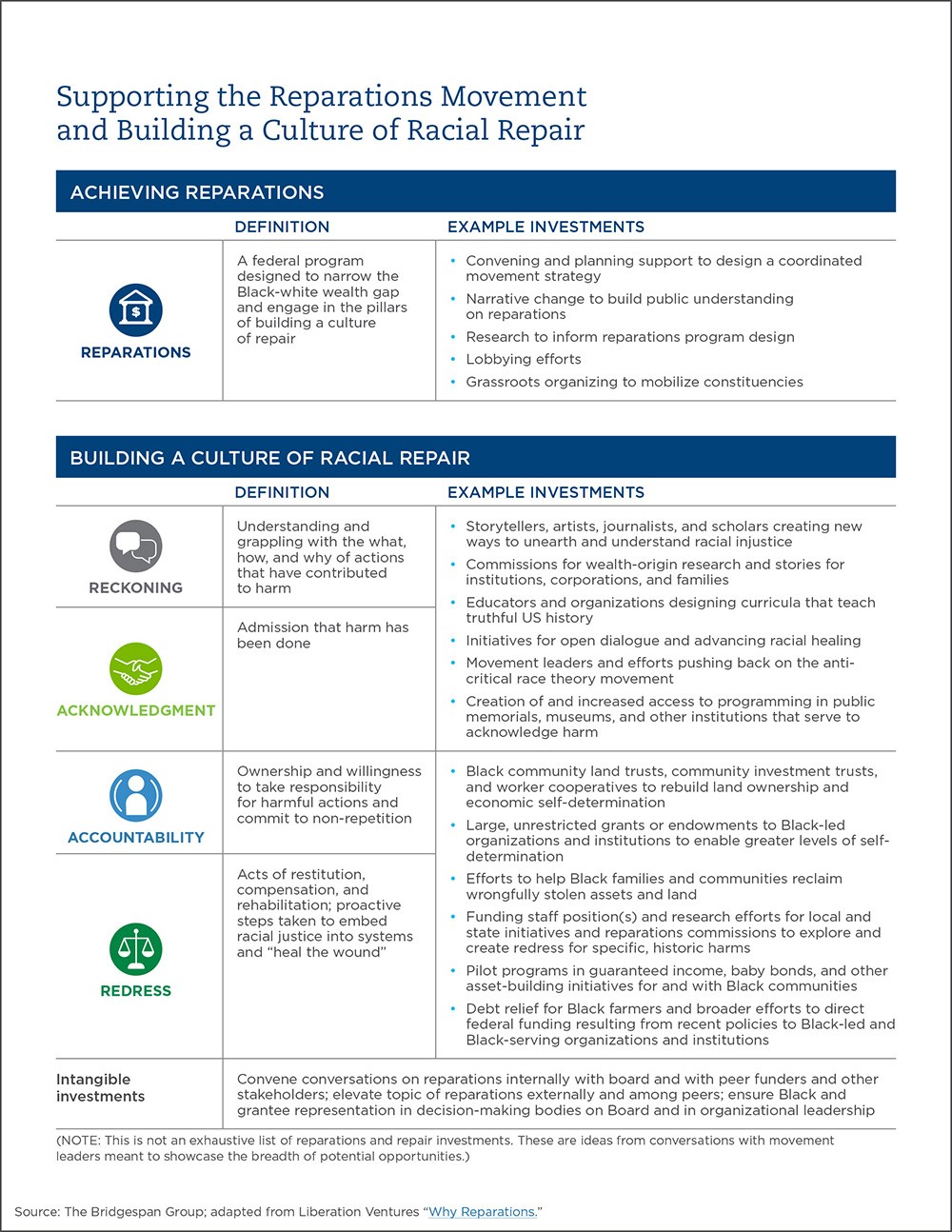

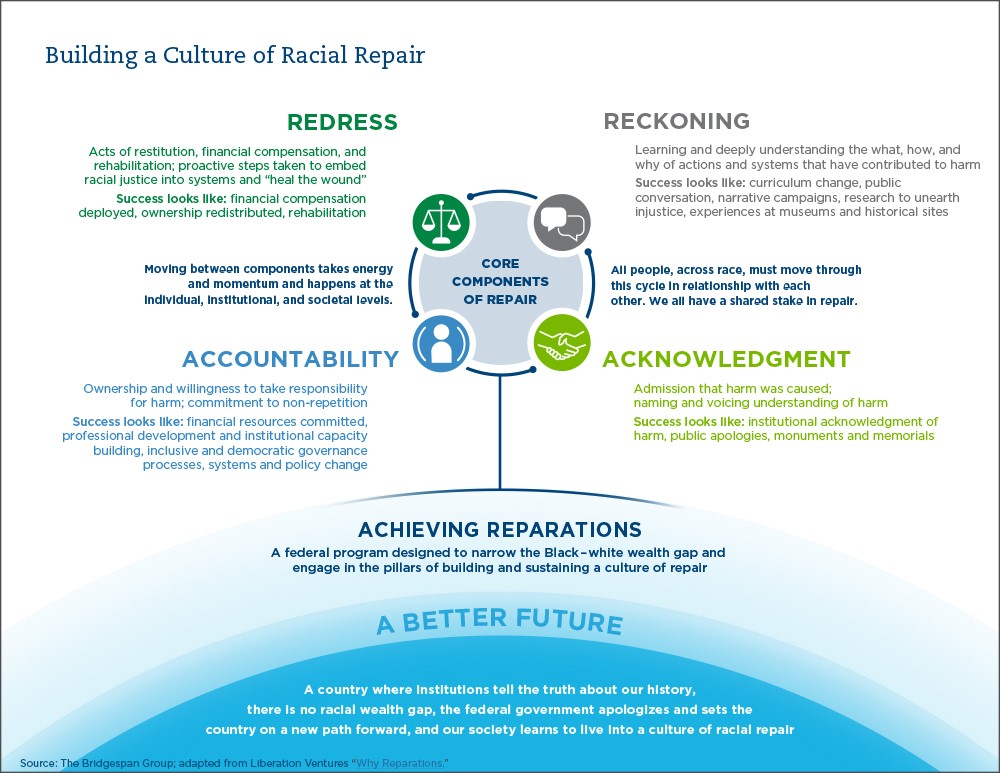

Essential to achieving reparations is building a culture of repair—the work required to cultivate norms, practices, rituals, and values for productively responding to harm (see image previous page). Liberation Ventures offers one way of thinking about racial repair with a framework that consists of an ongoing, iterative cycle of reckoning, acknowledgment, accountability, and redress.

The process of moving toward reparations and creating a culture of repair gives us the opportunity to become a nation where the racial wealth gap narrows; institutions tell the truth about our history; federal, state, and local governments and institutions apologize for harms; and we all enjoy the power of a multiracial democracy, by and for all the people. Critically, raising the issue of repair does not imply that the Black community is broken, damaged, or defined by victimhood. Instead, what is damaged and in need of repair are the policies, systems, and culture that created and sustained the harm and inequity reparations address. Therefore, all people, regardless of race, stand to benefit and have a role to play.

Despite this holistic definition, much of the public discourse around reparations often focuses on specific dollar amounts and who exactly would be paid. In regard to the recent work of the statewide reparations task force in California, one philanthropic leader confided, “What do you think [that price tag] does politically? It hands a weapon to others who want to increase divisions.”

Putting the focus only on the price tag, out of context, is a shock-and-awe approach that paralyzes the broader discussion into a state of impossibility. Daniel Anello, CEO of Kids First Chicago, points out: “The only way we don’t get sticker shock is if people really understand their history, and how we got to where we are, which is one of the pillars of comprehensive reconciliation.”

Movement leaders we spoke with are much more concerned with the racial repair, healing, and opportunity that reparations can bring to the entire nation. Ward is quick to point out that the Bruce’s Beach success is not full reparations because it was not accompanied by additional forms of repair. Indeed, after the land transfer, it took the city of Manhattan Beach two years to formally apologize, an initial step toward repair.10

This article focuses specifically on Black people because of the history and significance of Black-white dynamics in shaping the United States. That does not mean that historical and ongoing injustices to Indigenous, Latinx, or Asian American communities are in any way being overlooked. Given the depth of inequity that has been systemically imposed on Black people, an America where all Black people can thrive is one where all Americans must be thriving too.

“It is so important to understand history within the context of the Black-white paradigm because the protocols of anti-Blackness have become the protocols of oppression for the nation. So, understanding that history is important if we want to create a nation that can have a thriving democracy,” explained Angela Glover Blackwell, founder in residence at PolicyLink, when asked about reparations at a Stanford Social Innovation Review “Frontiers of Social Innovation” conference in 2023.

“It is so important to understand history within the context of the Black-white paradigm because the protocols of anti-Blackness have become the protocols of oppression for the nation.”

Furthermore, movements for equity and justice are often working in solidarity with one another. (For more on the Land Back movement, which includes Native reparations in addition to Indigenous self-determination, see the work of the NDN Collective and Sogorea Te’ land trust, as well as Indigenous-led funding opportunities curated by Neighborhood Funders Group.)

It is also critical that we apply an intersectional lens to reparations. For instance, redress for a cis Black man might look different than it would for a queer disabled Black woman or for a trans Black woman, because these individuals are likely to have experienced different harms based on their particular identities. Likewise, the most common narratives of enslavement depict labor “on the backs” of Black men, which erases the significance of Black women’s labor, along with the labor of their forced reproduction, in the nation’s history.

Scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw, founder of the Center for Intersectionality and Social Policy Studies at Columbia Law School and co-founder the African American Policy Forum, warns that disconnecting the experience of Black women from the history of enslavement and its legacies ensures the dynamics of harm will continue to be repeated. “Until we are able to acknowledge that the wealth disparity came through Black women’s wombs, our effort to advance a reparations frame is going to be incomplete,” says Crenshaw.

Reparations Are Not a Radical Solution, Though the Impact

of Repair Will Be

“It is obvious today that America has defaulted on this promissory note, insofar as her citizens of color are concerned. Instead of honoring this sacred obligation, America has given the Negro people a bad check, a check which has come back marked ‘insufficient funds.’” —Martin Luther King Jr., “I Have a Dream,” August 28, 1963

Reparations for Black people in the United States is not a new idea, although the movement has gained more media attention in recent years, thanks in part to the writing of Ta-Nehisi Coates and Nikole Hannah-Jones, as well as attention raised by Black Lives Matter in the aftermath of the police killing of George Floyd. The unfulfilled promises of “40 acres and a mule” issued in 1865 after the Civil War anchored the earliest discussions on reparations.11 But the call actually dates back even further, thanks to Black women. Belinda Sutton, an Africa-born woman who was enslaved by landowner Isaac Royall Jr., is considered one of the first people to demand reparations for slavery and win—petitioning the Massachusetts General Court in 1783.12

In fact, the United States has even paid reparations for slavery before—not to Black people, but rather to slaveholders. In 1862, almost a year before he signed the Emancipation Proclamation, President Abraham Lincoln signed a lesser-known bill, the District of Columbia Emancipation Act, that paid up to $300 (approximately $9,010 today) to slaveholders loyal to the Union for every enslaved person freed.13

And, a century and a quarter later, President Ronald Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act, which gave a formal apology for the incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II and paid $1.6 billion to survivors.14

Reparations are also a global concept. In 2022, New Zealand became the most recent country to implement reparations when it made reparations to the Ngāti Maru, one of its indigenous peoples.15 Recently, King Charles of Britain has even given the crown’s first support for research into the monarchy’s slavery ties.16 After World War II the United States, via the Marshall Plan, also helped to ensure that European Jews received reparations for the Holocaust.17 Since 1952, to foster societal healing, Germany has paid more than $80 billion euros18 to Holocaust survivors and started the journey of ongoing truth-telling and work to preserve the legacy and memory of victims and survivors.

Truth and reconciliation commissions have been used in various forms around the world to help nations heal from human rights atrocities.19 In South Africa, such a commission was spearheaded by Desmond Tutu and Nelson Mandela and is praised for the public airing of the physical and psychological harms of apartheid inflicted on Black South Africans. To be sure, the approach is also criticized because accountability and redress fell short, in that reparations payments were minimal and no perpetrators were prosecuted, while some received amnesty.20

Today, the reparations ecosystem in the United States includes a robust mosaic of Black- led organizations and multiracial coalitions. Grounding the movement are long-time advocates and veteran organizations like N’COBRA (National Coalition of Blacks for Reparations in America) that have been doing this work for decades. Building on their legacy are a swath of newer organizations tackling a wide range of work: narrative change (e.g., Media 2070), policy advocacy (e.g., Why We Can’t Wait coalition), racial healing (e.g., The Truth Telling Project), and state and local advocacy (e.g., FirstRepair). Intermediaries, such as Liberation Ventures (collaborator on this article) and the Decolonizing Wealth Project, are organizing donors and redistributing funding across the movement. The field is also beginning to build out its research infrastructure (e.g., with organizations like the African American Redress Network) such that the movement is better equipped to educate, advocate, and connect with other movements.

Momentum is building. Currently, reparations and racial repair activities are happening across all 50 states. In 2021, Evanston, Illinois, became the first city in the United States to create a reparations plan for its Black residents in the form of housing grants.21 FirstRepair, founded by Robin Rue Simmons, the former Evanston alderman who led the effort for the bill’s passage, is currently in conversations with more than 100 initiatives on the local and state level that have taken some step toward reparations. A consortium of more than 90 universities across the United States, United Kingdom, and Canada are investigating their own institutions’ ties to slavery and the legacies of racism in their histories.22 In 2022, the United Nations called on the US government for the first time to begin the process of providing reparations for descendants of enslaved Black people.23

And, in 2023, Representative Cori Bush introduced the Reparations Now Resolution, following a decades-long tradition of introducing a federal bill on reparations in every legislative session.24

Philanthropic involvement in the movement is growing, too, with national organizations entering the space. At least 80 national funders, including the Ford Foundation, MacArthur Foundation, Hewlett Foundation, and the Rockefeller Brothers Fund, among others, are supporting multiple actors in the reparations ecosystem.

“When it comes to reparations, it is not a matter of ‘if’ it will happen—it is happening right now,” says attorney and activist Nkechi Taifa, founder of the Reparation Education Project. Taifa, who has been working on this issue for 40 years, sees the momentum now as at an all-time high. Her message to funders: “The opportunity is here, the opportunity is now. You can either be on the cutting edge to make transformational change happen or regret not doing so later.”

Still, despite the long history and precedent to employ reparations, well-funded opposition forces to equity have made the mere word “reparation” toxic, despite its linguistic roots in repair. “We have a hugely asymmetrical situation where hundreds of millions of dollars are basically being spent trying to shift understanding away from the idea that there’s still race work that needs to be done,” says Crenshaw, “and that there’s still racial repair that needs to happen.”

The fruit of those anti-equity efforts includes the introduction of more than 563 anti-critical race theory measures in 2021 and 2022 aiming to regulate how race is discussed in the United States; almost half (241) are now in effect.25 The topic of reparations was also cut from the required topics in the new AP African American studies curriculum. In addition, in a sign of the symbolism of the word itself, the shooter of the racist massacre in Buffalo, New York, wrote “Here’s your reparations!” on the assault rifle used to steal 10 Black lives.26

“We have a hugely asymmetrical situation where hundreds of millions of dollars are basically being spent trying to shift understanding away from the idea that there’s still race work that needs to be done and that there’s still racial repair that needs to happen.”

At a recent reparations conference, tight security and regular warnings to attendees not to post the location of the conference hotel served as a reminder that some movement leaders in the room receive routine death threats as a result of doing this work. In our own conversations, there were some funders supporting reparations work who purposely don’t use the word publicly. Movement leaders stressed the need for funders to use their influence, voice, and convening power to foster education and collaboration.

Dr. Luke Charles Harris, co-founder of the African American Policy Forum, reminds us to stay focused on what matters: “What we should be afraid of is white supremacy, not reparations.”

Repair Is Possible, and Now Is the Time

“Reparations would look like Black people making their own businesses and collectively owning land and building houses on our own land. It looks like beloved community, where we could determine our future for ourselves, our children, and our families.” —Mike Milton, founder and executive director of the Freedom Community Center

Our interviews illustrated that the work of reparations and repair is wide ranging. While philanthropic organizations cannot themselves pay reparations, the abundance of imagination and variety of entry points is a reminder that there is no lack of opportunity for philanthropy. See the table on the next page for examples of what this work can look like. We dig deeper into this topic with funder examples in our companion article for Stanford Social Innovation Review, “A Reparations Roadmap for Philanthropy.” In addition, Liberation Ventures is co-creating with movement leaders the Reparations Grantmaking Blueprint, available in early 2024, that will include a full picture of the strategic investments necessary to build momentum over the next 10 years.

We also invite you to take a look at some of the exciting work across the movement in the Reparations Movement Profiles here on our website, which showcases organizations working toward reparations and repair in critical lanes:

- Land ownership. Land theft contributes to the racial wealth gap.

- Criminal legal system. The War on Drugs disproportionately harms Black communities today.

- Media. Anti-Black narratives spread by the media since colonial times help ingrain inequities.

- Education. The erasure of the nation’s “hard history” prevents understanding of root causes of inequity.

These efforts to address specific harms can create tangible psychological and material benefits for affected Black communities and serve as valuable pilots of learning and innovation. Such efforts are also critical to building momentum toward the ultimate goal of achieving reparations and building a culture of racial repair.

“For me, there’s no way to get to equity without reparations,” says Richard Wallace, founder and executive director of Equity and Transformation. “Fixing inequity is very simple—put the resources stolen from our communities back into those communities. Fixing the racism that caused inequity is the hard part.”

Click the image to enlarge

The authors thank Lyell Sakaue, a partner in Bridgespan’s San Francisco office, for his thought partnership and critical contributions to this research. We also are deeply grateful for and inspired by the pioneering organizations and movement leaders who were interviewed for and are quoted in this piece. In addition, we recognize that this research stands on the shoulders of the work of so many across time who have been fighting for reparations since before emancipation. We believe that we can win reparations in our lifetime—and we owe that belief to the giants who knew that they likely would not see success in theirs, yet still worked tirelessly to cover so much ground before us.