“Our network moves too slowly. The way we’re structured, it can take us so long to get things done.” Talk to leaders of large national and global nonprofit networks—and we talked to many before COVID-19 hit—and you’ll hear this refrain again and again. Now, amid the coronavirus pandemic, it is clearer than ever that networks will need to be able to make decisions more quickly. This may be the time to explore different approaches to decision making—approaches that can then remain in place even after the current crisis wanes.

It often takes 12 to 24 months to move decisions through a network, even when there is broad support. True, networks can be very large: they make up nine of the 10 largest US-based nonprofits. And they tend to have complex governance structures, which can seem like legacies of a bygone era. But in working with more than a dozen large nonprofit networks over the last five years and reviewing the decision-making practices of more than 20 nonprofit networks and for-profit franchises, our Bridgespan team has observed that it is often the culture of decision making rather than governance that accounts for the slow pace—and that this culture can be understood and evolved to enable faster decisions.

Of course, speed isn’t the only element in decision making. As research by Bain & Company shows, decision effectiveness also involves the quality of decisions and the way they’re translated into action. High-performing organizations do well on all these dimensions. But it is clear that for many networks, the glacial pace of some decision making is a particular challenge.

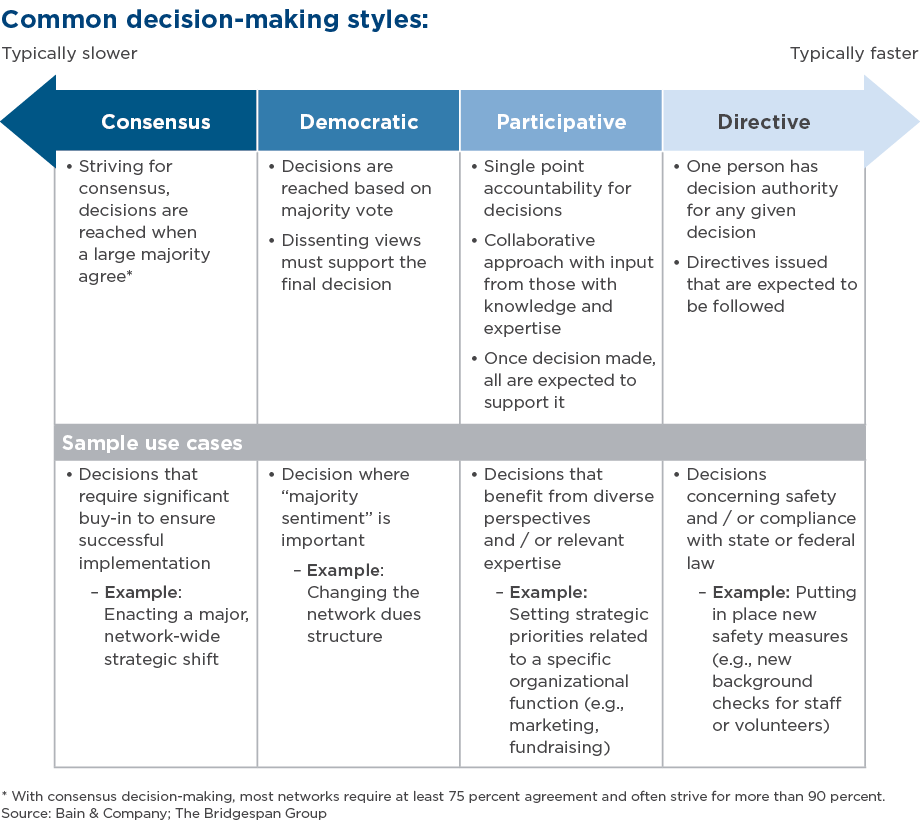

One way organizations can speed up some of their decisions involves using different decision styles for different types of decisions. The graphic below describes four key decision styles and outlines the types of decisions that could often fall into each.

Most large networks, particularly those that are federated, formally embrace a democratic decision style, meaning they make decisions through a majority vote of the network members. Yet we have observed that the predominant style ends up being consensus. This distinction between the decision style dictated by the governance model and that used in practice underscores that it is the culture of decision making rather than governance that often accounts for the slow pace.

For some decisions, seeking consensus is vital and worth investing a lot of time and effort to achieve. As a CEO at a federated nonprofit network noted of the gravitational pull toward high levels of participation and consensus, “Unless you have the dialogue and deliberation, decisions will blow up at the eleventh hour.” This is true for the most important decisions that affect the full network and where broad buy-in is critical for successful implementation.

But this culture of consensus can create a time-consuming, one-size-fits-all approach to decision making and reduce the network’s agility. In cases where speed is needed or the decision will only impact a subset of network members, seeking consensus, or even using a democratic style, may not be the default approach.

Consider the case of one federated network focused on global poverty and humanitarian aid. For most major decisions that affect the full network, each affiliate gets one vote—and that takes time. However, this global network has a critical exception for its disaster relief efforts, which last year reached millions of people. In a crisis, when rapid response is paramount, it does not bring decisions to a vote of the full network. Rather, its humanitarian committee makes and implements them very quickly with knowledge of what’s happening on the ground. This small group, which network members select and empower to make decisions on their behalf should a crisis hit, has the authority to move resources and funding from other parts of the network in order to address the disaster at hand. As the COVID-19 pandemic shows, even networks not typically engaged in emergency relief may need a similar body to make fast decisions in time of crisis.

Similarly structured networks in the private sector commonly employ different decision styles depending on the decision type. One very large global fast-food franchise explicitly tailors its style according to the importance of achieving uniformity across the network and of deciding things quickly. Though the central office has ultimate authority, it will often make pricing decisions democratically through a vote of the franchisees, with each franchisee getting one vote regardless of size. These decisions are not binding on all franchisees. For highly strategic decisions where uniformity is paramount—for example, what items should be on every menu—it uses a participatory style whereby the franchisees provide input to the central office but do not vote, and the decisions are binding.

Another example comes from a centrally-controlled global environmental network we studied. Some years ago, it tried to raise chapter fees through a quick board decision. There was significant blowback, prompting the organization to carefully match decision style to decision type. Today, it works for consensus when the decisions involve broad network-wide strategy. But for other important but less far-reaching questions, like personnel, it makes decisions more quickly using a directive style. For instance, the network’s leaders have exerted their authority to strengthen affiliate management by replacing a significant number of chapter directors.

With a crisis upon us, and a potentially long and challenging post-crisis period to follow, now is an important time for more nonprofit network leaders to adopt this kind of close attention to decision-making style and open up opportunities to make decisions faster. Here are three steps to get started:

- Create a list of critical decisions within the network that move slower than seems desirable.

- Identify what decision style is being used for each.

- Identify the decisions for which a different, faster style might be possible.

For more on nonprofit networks:

- Decision-making is one aspect of a network’s overall operating model. To read more, see “Operating Models for Nonprofit Networks.”

- Bain & Company has developed important insights on decision-making which can be useful for the nonprofit sector as well. See: “The Five Steps to Better Decisions” and “The Decision-Driven Organization.”

Mark McKeag is a partner and Lindsey Waldron is a manager in The Bridgespan Group’s Boston office. They thank Bradley Seeman for his editorial support in writing this article.