Foreword

For most for-profit companies, steady growth is the surest path to success. How to grow—whether by opening new divisions, developing branches or franchising operations, acquiring other companies, or taking any number of other possible approaches—comes down to a matter of choice and opportunity for each individual company. Whichever path a company pursues, more often than not it can be assured it will have access to ample information about the benefits and risks of each option, talent to help execute its chosen strategy, and money to finance its growth.

In the nonprofit sector, the picture is much different. Few, if any, of those same resources are available to growth-minded nonprofits—especially organizations in the social-service sector that aspire to serve more people.

Related Content

This is one of the first truths our two organizations had to confront when we began working together several years ago to strengthen organizations in the youth-service field. Through its grant-making, the Edna McConnell Clark Foundation helps high-performing youth-serving organizations develop and then implement growth plans that the Foundation and they hope will lead to better services provided to more and more young people from low-income backgrounds. The Bridgespan Group, through its work with the Foundation and others, helps high-performing nonprofits develop viable strategies for increasing their social impact while building knowledge for the sector more broadly.

Our collective understanding of the state of the field and the challenges facing organizations that want to become healthier, stronger, and more effective has been deepened by our work. At the same time, gaps in our knowledge about the nature of growth in the nonprofit sector have become more obvious. To explore some of these issues and to help answer questions that might enable us and others interested in building stronger nonprofits be more effective, we undertook this study. Over the course of several months, leaders of 20 youth-serving organizations that grew significantly in recent years took part in extensive interviews about their experiences. They also allowed us to develop individual case studies to further illuminate the changes the organizations went through over the years. In addition to the interviews and case studies, researchers collected data on well over 1,000 youth-serving organizations around the nation.

As the study shows, nonprofit organizations that are intent on expanding the scale of their services face notable challenges. For example, even after years of growth, the financial condition of well-known and good-sized youth-serving organizations remains remarkably fragile. Funding for organizational improvements consistently lags the need for them, putting stress on the entire organization and particularly its leadership. Contrary to experiences in the corporate sector, economies of scale and operating efficiencies are hard to come by. And though foundations can and sometimes do fund growth, they are unlikely to sustain it. Accordingly, the need to think about fundraising never lessens but rather becomes a greater and greater challenge the larger an organization grows.

These and many other observations are to be found throughout this white paper. For them, we are indebted to the organizations that agreed to participate in the tedious business of responding to questions, questionnaires, and extensive interviewing.

In the end, of course, this effort will only be meaningful if the information it contains is useful to other foundations and funders that are committed to building a stronger and more effective nonprofit sector, and to the nonprofit organizations that are thinking about growing. To them—and the potential social good they represent—we dedicate this report.

Michael A. Bailin

President

The Edna McConnell Clark Foundation

Jeffrey L. Bradach

Managing Director & Co-founder

The Bridgespan Group

Introduction

Growth is a critical component of strategy for many organizations that directly serve youth and those that support them, including ours. The Edna McConnell Clark Foundation (EMCF) pursues its mission of “improving the lives of people from low-income communities” by “helping high-performing nonprofit organizations increase their capacity to serve more young people from low-income backgrounds (ages 9 to 24) with quality programs during out-of-school time.”[1] The Bridgespan Group’s mission is to “work to build a better world by strengthening the ability of nonprofit organizations to achieve breakthrough results in addressing society’s most important challenges and opportunities.”[2] Aiding direct-service organizations in their efforts to develop and implement strategies with the potential to achieve significant results through growth is a fundamental aspect of the way in which Bridgespan seeks to accomplish its mission.

Growth is a noteworthy phenomenon among organizations that serve youth. Between 1997 and 2002, the number of organizations in the youth-service field grew by 41 percent, while the funds those organizations received grew by 70 percent from $4.7 billion to $8 billion. Of this new funding, two-thirds (some $2 billion) was invested in established organizations, while the remainder went to nonprofits created during this period.[3]

For both of these reasons, in January 2004 EMCF commissioned a research project of which this white paper is a part. Together, we set out to explore growth in U.S. youth-serving organizations: the prevalence of growth, the factors that were critical in shaping how these organizations grew, and the major consequences of growth. We hoped that by increasing our understanding of this phenomenon, we could become more effective in our own work. We also hoped that these efforts would be useful for other organizations committed to supporting nonprofits that serve young people.

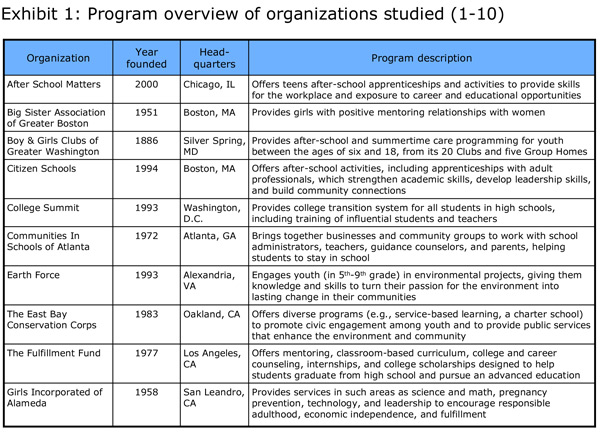

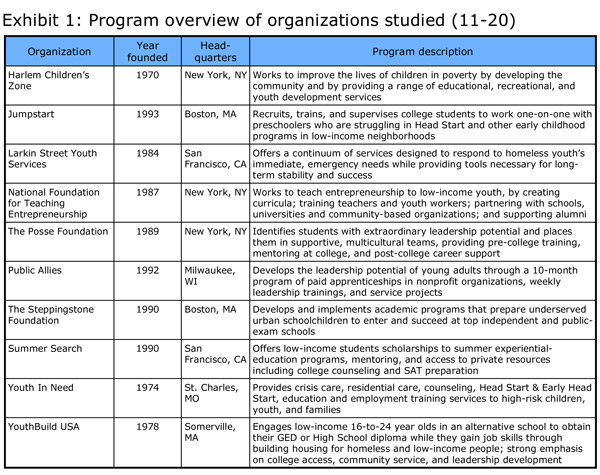

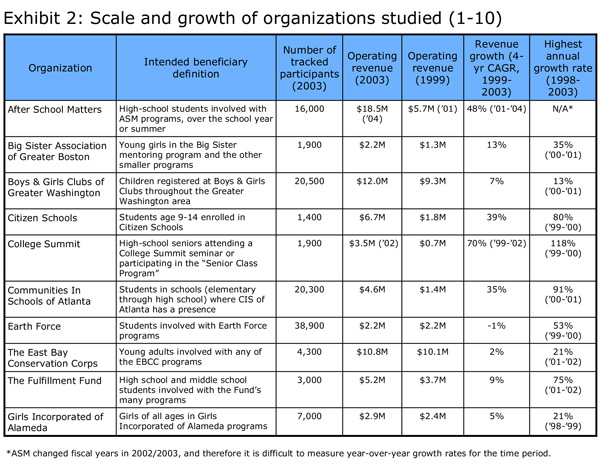

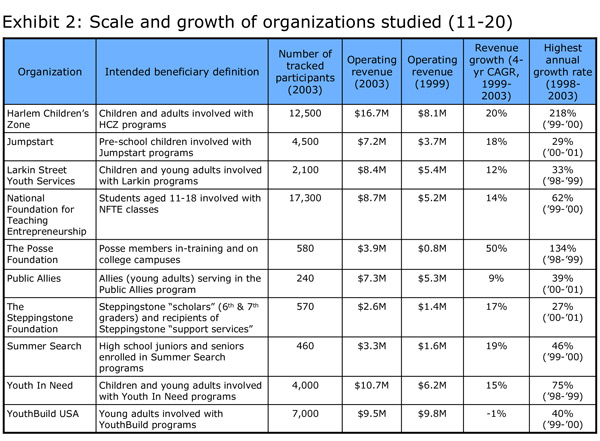

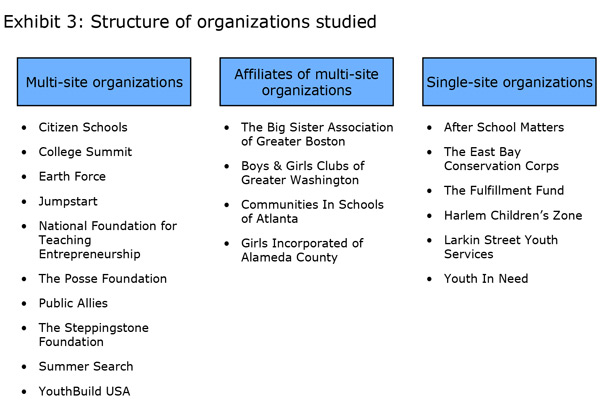

One of the chief components of the study was an in-depth look at 20 youth-serving organizations that experienced significant growth in recent years. Exhibit 1 provides a brief overview of each of the participating organizations. Exhibit 2 provides data on the number of youth each served in 2003 and its revenue growth from 1999 through 2003. Exhibit 3 shows a breakout of these organizations into three categories: organizations that attempted to expand nationally (multi-site); organizations that grew locally or regionally (single-site); and local affiliates of established national organizations. (Appendix B discusses the methodology of the study.)

Over a period of four months, members of the research team visited the participating organizations to interview key members of the management teams and, in some cases, members of their boards. In these and subsequent discussions, we asked a wide range of questions addressing six main topics:

- The organization’s motivation for growth and the extent to which growth was planned;

- The form that expansion had taken;

- The ways in which growth was financed;

- The extent to which growth involved changes in and/or codification of the organization’s program and attempts to measure program outcomes;

- The kind of changes that took place within the organization in response to growth;

- Factors external to the organization that affected its growth.

In addition, during this phase and in the months following it, we gathered quantitative data about the revenues and costs of each of these organizations, reaching as far back into their growth history as their records would allow. Further, we surveyed the participants to quantify a number of the observations that emerged from the interviews. Finally, we gathered the executive directors (or their equivalents) of the 20 organizations in New York to present a preliminary version of the study’s findings, both testing their accuracy and developing new insights from the discussion.

This research produced a wealth of information about the experience and effects of growth in youth-serving organizations—far more than could be encompassed in a single document. As a result, we have chosen to present the material in two formats: a series of 20 case studies, which capture the particulars of each organization’s growth story; and this white paper, which presents the observations that emerged most consistently across the interviews and data-gathering process.

Broadly speaking, these observations fall into four categories: the path of growth, the financial consequences of growth, the organizational consequences of growth, and the “chutes and ladders” of growth (i.e., those factors that helped or hindered these organizations as they grew). In the pages that follow, we look at each of these topics in turn and then conclude by offering some ideas about the implications of the study for funders, like EMCF, that want to support the growth of effective youth-serving organizations.

Before beginning, however, a few cautions are in order. First and foremost, it is worth underscoring what a study such as this can—and cannot—do. Taking a relatively intensive look at 20 organizations allowed us to consider varying approaches to a common set of challenges and to identify a number of apparent trends. At the same time, these 20 organizations do not constitute a representative sample of youth-serving organizations, nor is the sample large enough to allow the results to be of statistical significance.

Second, because the effect of growth on youth-serving organizations was one of the project’s chief concerns, we excluded nonprofits that failed to grow—or chose not to grow—from the study. As a result, while these pages include examples of practices that appear to be reasonably effective in supporting successful growth, the most we can say is that these are current practices, not that any individual one of them represents a “best” practice.

Finally, in choosing examples of successful growth, we defined success in terms of the quantity of services offered (as measured by growth in the number of youth served and in the organization’s revenues) and not in terms of the quality and effectiveness of those services (as measured by good youth-service programming and by positive effects on the participants). To assess the latter, we would have had to evaluate each program and compare the results of growth to other options (such as program improvements) that the organization itself could have taken or that its funders could have supported—both of which were beyond the scope of this study. As a result, inclusion in this paper reflects neither positively nor negatively on the nature nor effectiveness of the programs these organizations provide, but only on the fact that they were able to expand significantly the delivery of those programs.

The Path of Growth

One of our study’s central objectives was to understand how and why this set of organizations had grown. In the interviews we asked participants about their organizations’ motivation and planning for growth as well as about the form that growth had taken. While the answers were many and varied, two trends emerged: the interplay between opportunity and strategy as the organizations grew; and the need for multi-site organizations to balance—and rebalance—the degree of local autonomy and central control.

Observation 1: Growth was more often a response to opportunity than the result of strategic choice.

All these organizations grew because their leaders saw—and seized—opportunities to acquire funding, talented staff, or both. There were literally as many examples as there were participants. Organizations like NFTE, Youth In Need, and Communities In Schools of Atlanta were responsive to funders who wanted to see them run more programs in more areas. Summer Search went to Boston because of Jay Jacobs, then a site leader and now the CEO. “Why Boston,” founder Linda Mornell commented. “Because I met Jay and that was where he lived.” Earth Force president Vince Meldrum described a similar approach to expansion: “If we can find the right staff members, then we go there. [Starting a new site] is a 70-hour per week job, and it takes a very committed individual.”

Given the difficulty of acquiring resources, and the fact that few (if any) nonprofits can fund their own growth, it is not surprising that seizing opportunities as they presented themselves figured prominently in these organizations’ growth stories. The challenge lay in differentiating genuine opportunities from will-o-the-wisps, which could compromise or even undermine their missions. As Chuck Harris, a member of College Summit’s board and its interim vice president of development noted, “There is a risk of being diverted [from our mission] by good ideas. This is especially apparent in foundations’ [requests for proposals].” Cognizant of this danger, College Summit is attempting to raise a multi-million dollar fund that would allow it to focus on its core services over the next few years while sustaining its growth.

A few of the organizations in the study admitted to having to rationalize the addition of some programs retrospectively and, in some cases, changing the mission (as many as three times) to reflect the new direction. While such growth could be exciting to both staff and funders, it could also be confusing: “Ask 100 people in this organization why we’re here,” one CEO admitted, “and you’ll get 100 different answers.” To manage the risk of mission drift, many of the organizations in the study appeared to be moving toward what we have called “strategic opportunism.” By this, we mean that they were developing explicit criteria (such as a designated level of community support, availability of funding, presence of qualified staff, and/or connectedness to mission or strategy) for screening growth opportunities.

The Posse Foundation is one of the most stringent organizations in this regard. A new site must have at least three years of start-up funding secured before expansion can take place. Before opening a new site, Posse also performs a feasibility study, which examines not only funding opportunities, but demographics, geographic realities, and the level of demonstrated need among public-school children. For Earth Force and Summer Search, the critical factor is having qualified staff to lead new sites. For example, even though Summer Search had secured both community support and funding for a new office in Seattle, they waited two years to open the site, until they had identified the right director.

In several cases, the learning-by-doing of early growth initiatives underscored the need for a more deliberate approach. Jumpstart, which at first would “go anywhere,” according to Rob Waldron, its current president and CEO, because, “it’s like being asked to the prom, you’re just so glad to have been asked,” now thinks more actively about the operational challenges of managing a geographically-dispersed network. Similarly, NFTE’s president and founder Steve Marrioti described how: “From 1987 to 1990, we were just trying to stay alive. I was totally open. Now it is more structured, and I think it is better.”

Both NFTE and College Summit supplemented their experiential learning by engaging in a formal strategy process, which helped identify the prerequisites for successful growth. Recognizing that they would need to develop a strong presence in (and therefore invest deeply in) specific communities to effect significant change, College Summit developed a list of criteria for prospective geographies. It also drew back from certain locations it had already begun to explore. Using another approach to managing risk, Girls Incorporated of Alameda County created a tool which includes a clear set of criteria for evaluating how well a new program opportunity fits with the organization’s mission.

The experience of these organizations points to the importance of being deliberate about responding to growth opportunities. It also suggests the potential usefulness of viewing strategy not as an unchanging roadmap but more as a set of guardrails within which new opportunities can be pursued. As Patty Pflum, the executive director of Communities In Schools of Atlanta commented, “our strategic plan helped us be able to say ‘no’ to certain things.” By carefully screening prospects that came their way, the organizations could reduce the likelihood that they would be pulled in directions that would distract them from their missions and strain their capabilities.

Observation 2: For organizations with multiple sites, finding the right balance between local autonomy and central control was a recurring challenge.

Nonprofits engaged in replicating programs in new geographic locations can be arrayed along a spectrum according to the level of control maintained by a central office or headquarters.[4] At one end of the spectrum are organizations that try to expand their reach by sharing their model with other organizations, formally or informally.[5] At the opposite end of the spectrum are organizations that choose to expand by building branches, with a single national office holding both ultimate decision-making power and the organization’s 501(c)(3) designation. These branches can be organized in ways that are characterized as tight or loose, depending on the degree of control exercised by the national office over the branches’ governance, financial operations and programs. Between these two extremes are nonprofits that have grown by creating some sort of partnership or affiliation with other independent 501(c)(3) organizations. In many cases, the responsibilities of each party are contractually defined and, as is the case with branches, these affiliate relationships range from tight to loose.

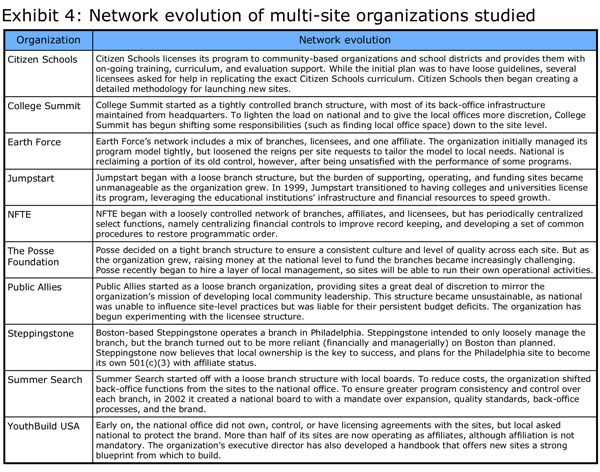

The multi-site organizations we studied chose different points along this spectrum of control to begin their geographic expansion. For example, Public Allies and YouthBuild USA started out with far less central decision-making than Earth Force and Posse. Over time, however, all of them moved away from either end of the spectrum to organization structures that encompassed both aspects of centralization (national control or site uniformity) and elements of decentralization (local autonomy and site variability). Several set out by trying to empower their sites as much as possible but reduced local autonomy when the sites ran into trouble or demanded more control. Others—principally organizations that were particularly sensitive to maintaining a consistent program model, quality, and culture—started out relatively centralized but delegated more autonomy to their sites when the organization became too costly or complex. (Exhibit 4 provides a snapshot of each organization’s evolution. For more detail, please see the case studies.)

The organizations that evolved from a structure in which local sites operated with complete, or almost complete, autonomy toward one with a greater measure of central control tended to be: (1) responding to requests from the sites for quality control and/or reinforcement of the brand; or (2) striving to share costs or manage risk.

For example, YouthBuild USA founder and president Dorothy Stoneman wanted to spark a national movement, not build a national organization, so “we started by giving everything away—our knowledge and our name.” YouthBuild USA provided a handbook, inspirational training, and on-site technical assistance coupled with full local autonomy with no contractual affiliation agreement for use of the YouthBuild name. When federal funds were appropriated for the program, however, the first 15 sites sat her down and asked for protection from opportunists seeking funds from HUD who might undermine YouthBuild’s reputation by not adhering to the philosophy and program design. As a result, YouthBuild USA and these directors created standards for affiliation and use of the brand name, and further codified the program in a series of five handbooks. Initially, Citizen Schools also contemplated a relatively loose structure, but the model evolved to a more tightly managed affiliate system. Summer Search has begun looking for ways to minimize back office costs by centralizing certain functions that historically have been handled by individual sites.

The organizations that sought to devolve responsibility from the national office to the branches were motivated primarily by the difficulty of attracting sufficient funding and/or talented staff for all the sites. For example, Posse began delegating control so that site directors could run their own operations with greater autonomy. As founder and president Deborah Bial noted, “We can’t continue to raise the money [for all five branches] through one [national] office. It’s not healthy or smart. We’d like to give the program directors more power, more like executive directors, so they’re managing the office, raising the budget themselves.” The local directors will oversee local training, fundraising, and staff development, while the national office will retain oversight over training, finance, communications, university relationships, and local advisory boards.

Although there isn’t likely to be one best way to structure a national organization, making the wrong choice did place some of the organizations in jeopardy. The experience of Public Allies, for instance, made clear the importance of matching decision-making with fiscal responsibility. Within 10 years of its launch, Public Allies was operating branches in more than 10 cities and had financial and legal obligations for all that went on in these sites. Without the proper controls or staff in place, site directors began making decisions (such as leasing real estate and adding major program pieces) that had implications for the entire network, without consulting the national office.

Reflecting on what had happened, executive director Paul Schmitz pointed out some of the subsequent challenges. “There is minimal accountability for local site directors, because the national will always have ultimate responsibility for bailing local sites out. Replacing a poorly performing director is also very expensive, because it means there is no one raising money locally for several months and a new director takes time to build relationships.” Ultimately, Schmitz came to the realization that, “The structure we have is dysfunctional. The home office has all of the responsibility and little control. We either have to centralize more decisions, which goes against the culture of leadership development, or decentralize the structure and put liability where decisions are made. There are tradeoffs either way." In fact, in the time since our initial interviews, Public Allies has decided that all of the sites must affiliate with local organizations or universities in their communities.

Financial Consequences of Growth

Growth increases an organization’s need for capital at the same time that it increases its potential to achieve impact. As a result, it can be a double-edged sword, because greater ease in attracting new funds is seldom its reward. On the contrary, since capital is seldom allocated rationally in the nonprofit sector, successful growth usually makes the organization’s (and its leader’s) financial burden heavier, not lighter.

Observation 3: The financial condition of these organizations, even the best-known and fastest-growing, was remarkably fragile.

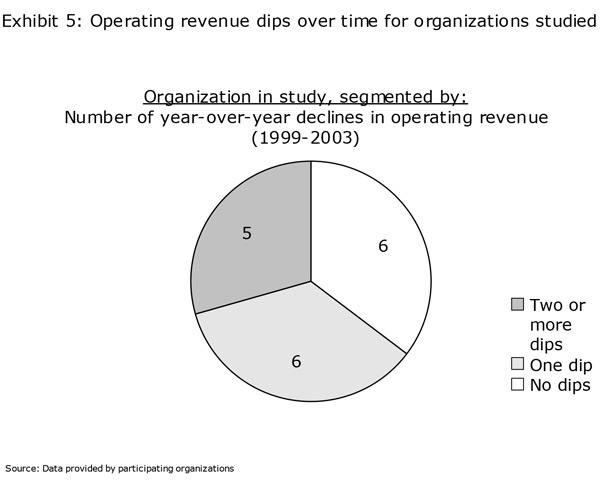

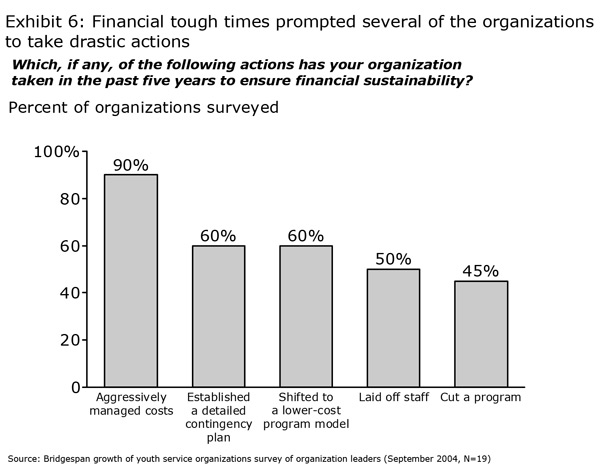

The organizations in this study are among the best known in the field of youth services. They take in average annual revenues of $7.3 million, and they have been in operation for an average of 26 years. Yet the degree to which they live on the edge financially might well stop for-profit executives dead in their tracks. Consider a few statistics: among the 16 organizations that provided data on this question, the average operating reserve was four-and-a-half months, and eight had two-month reserves or less. None had more than nine months of operating expenses on hand. Additionally, two-thirds of the organizations experienced at least one year of declining revenue between 1999 and 2003, and one-quarter dipped twice (Exhibit 5).[6] Over this same period, 50 percent laid off staff, 60 percent shifted to a lower-cost program model, and 45 percent cut entire programs (Exhibit 6).

The challenges facing Nancy Wachs, the executive director of After School Matters, are representative. The organization has strong support from the city of Chicago and its partners, and its programs are not currently in jeopardy. But the demand for its programs is huge, and funding has not kept pace: “We have a lot of support, but it is not always smooth. The city has been pushing us to grow faster, and they are helpful, but it is not always enough. And right now the parks have a big deficit, and the schools are having budgetary problems. Our programs are not in jeopardy, but the system is a bit precarious… To think that we would have to retreat from some of these schools makes me sick to my stomach. This program is a lifeline for a lot of these kids.”

Several organizations in the study have experienced the kind of drastic dips in funding that Wachs worries about. Communities In Schools of Atlanta nearly collapsed in the late 1990s, when they were unwilling to bid on operating a single-campus alternative school for 1,000 students rather than the small, dispersed sites of 150 students or less that they had previously operated. “There was a big layoff, a big reduction in staff,” said Theresa Crawford, director of finance and administration. “The remaining staff was scared, nobody knew what was going to happen.”

More recently, shifts in the prevailing political winds created enormous problems for all the organizations that relied on AmeriCorps appropriations. The East Bay Conservation Corps, which lost a $3-million grant in the early 2000s, cut staff, trimmed benefits, and did away with raises in order to preserve the number of students and youth participating in their programs. But even though they had planned for the possibility of the cut, morale plummeted, the level of uncertainty among the staff soared, and neither had stabilized at the time of our interviews. As Janice Jensen, the former COO, put it, “We’ve been getting hit from every corner… in large part because of AmeriCorps, but also because of the continued downturn in the economy, and the fact that many of our other funding sources have not been coming through for us.”

Financial crises were sometimes precipitated by the loss, or simply the delay, of funds from private sources. Earth Force, for example, was funded in full until 1998 by the Pew Charitable Trust, which had founded the organization in 1991. As Pew began to phase out its contribution, Earth Force was able to compensate for the lost funds; but its revenue growth rate slowed. Jumpstart’s white-knuckle ride occurred during the leadership transition from founder Aaron Lieberman to Rob Waldron, now the organization’s president and CEO. Despite the demonstrable success Jumpstart was having with its pre-school “scholars,” the organization was perhaps three months from insolvency, because funders were taking a wait-and-see approach to the leadership transition. As then board chair Jeff Bradach put it, “I don’t know what would have happened if Rob had said ‘no.’”

Salvation in times like these sometimes arrived in the form of a funder or a small set of funders willing to provide the resources necessary for survival. When Public Allies experienced a financial crisis in 2000, a board member stepped in to help cover debts incurred as the national office absorbed local sites’ deficits. “We were moving payroll to payroll in this period,” executive director Paul Schmitz remembered, and “we [had] cut through to the bone.” At Jumpstart, the board searched for and ultimately identified a foundation willing to provide an essential and immediate infusion of funds during the transition. YouthBuild USA also has received funding in times of near-desperation from foundations that had been long-time supporters. The board of Communities In Schools of Atlanta played a similarly crucial role by stepping in to raise emergency money from donors who had supported the organization historically.

Observation 4: Economies of scale and experience were evident for some of the organizations in the study but not for others.

Growth in the for-profit sector is often motivated by the potential to achieve economies of scale (the ability to share indirect costs over more products) and/or economies of experience (the ability to turn out products at a lower unit cost over time thanks to “smarter” production practices). The ability to realize these economic effects has long been a critical success factor in manufacturing; and it is becoming increasingly important for many for-profit service providers as well.

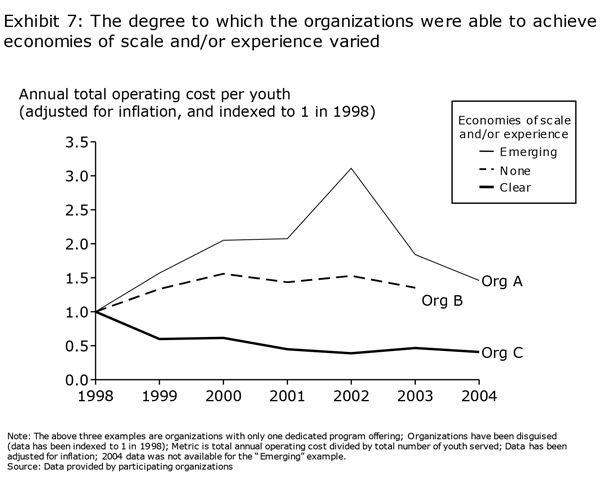

Whether nonprofit organizations have the potential to achieve similar economic gains without eroding their missions is an unanswered—and hotly debated—question. At the meeting in New York, this finding generated more discussion than any other, with compelling arguments offered on both sides of the question. The data from the study do not resolve the issue. Of the 10 organizations that were able to give us detailed and consistent cost breakdowns over time, two saw their cost per youth decline between 1999 and 2003; three saw a decline towards the end of the period; and five saw no general trend downward. (Exhibit 7 shows an example of each of these three archetypes.)

The interview data and the discussion among the participants at the New York meeting point to several phenomena that may explain why the majority of these organizations have not realized significant and consistent economies of scale and/or experience.

- Because several participants were still modifying or adapting their programs, neither their program costs nor their overhead costs were stable over time. Organizations such as Communities In Schools of Atlanta, which recently shifted from operating its own academies to working in the public schools, provided the most dramatic examples of this kind of programmatic change.

- The need to bring in more professional staff was widespread among the organizations, increasing their cost base and potentially offsetting any efficiency gains achieved in other areas. Fulfillment Fund and Larkin Street were among the organizations that had to bring in more seasoned (and more expensive) staff than the generalists and volunteers with whom they had begun their operations.

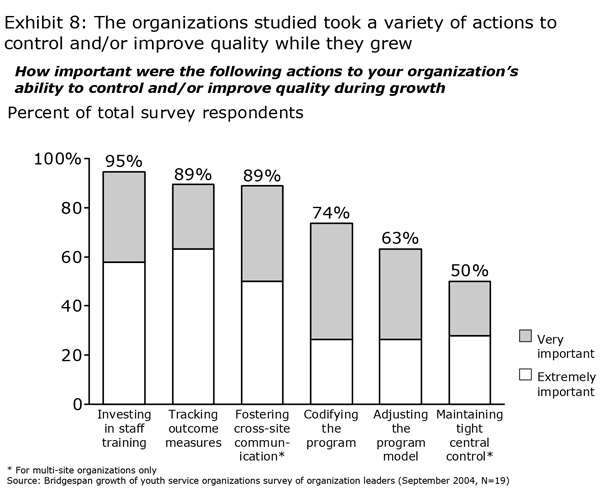

- Many of the organizations chose (implicitly if not explicitly) to increase the quality of their programs rather than pursue efficiency gains. These changes included investing in staff training, instituting processes for cross-site communication and sharing best practices, codifying and rounding out programs to better serve participants’ needs, and instituting and tracking performance metrics. (Exhibit 8 shows the range of activities organizations in the study took to maintain program quality while they grew.)

- Extremely high turnover rates and operating inefficiencies could be hard to eliminate for reasons largely outside the organizations’ control. For example, Girls Incorporated of Alameda County loses 80 percent of its part-time program staff every year, because its youthful employees tend to become overwhelmed by the magnitude of the issues facing their young clients. Jumpstart recruits college students, paid through work-study and/or AmeriCorps funds, to tutor disadvantaged pre-school children. From an economic perspective, the value of recruiting as many tutors as possible from a single university is unarguable. In practice, politics trumped economics, however, because of AmeriCorps rules about how many students can participate per campus. (That said, Jumpstart is one of the organizations that has successfully driven its cost per student down, by carefully codifying its operating systems and programs.)

It may be the case that in the next five years, more of the organizations in the study will experience significant reductions in their cost per youth. As we will see hereafter, many of them were investing significantly to build their capability; these investments—and the increased overhead costs they give rise to—could easily have dwarfed any savings achieved from scale or experience in the short-term. The fact that several organizations saw accelerating declines in their cost per youth toward the end of the period under study provides some evidence for this hypothesis.[7] Nevertheless, given the other issues highlighted above (i.e., program modifications, turnover, external forces, the pursuit of quality), continuing to question whether every youth-serving organization could, or even should, achieve economies of scale or experience effects comparable to those of corporations appears to be warranted.

Organizational Consequences of Growth

The need to professionalize staff and systems as the organization grew was a recurring theme in this study. Almost without exception, each participating organization reached a point where passionate commitment—and sheer will—from the leader and key staff were no longer sufficient to allow it to continue functioning well. Significant changes in processes, procedures, and roles were required, not only on the part of the leader and staff, but also on the part of the board.

Amid all this change, one thing did remain constant, however: the burden of fundraising borne by the leader. Whatever the capacity of the organization’s development staff, donors expected to maintain a personal relationship with the leader.

Observation 5: Bringing in a chief operating officer was often essential, yet just as often proved challenging for the organization’s leader as well as for the staff.

The organizations in the study commonly found that as they grew, the demands of daily operations coupled with the need to communicate constantly with the board, the public, funders, and key partners, overwhelmed the capacity of even the most tireless leaders. Staff began to observe bottlenecks, with day-to-day operating decisions getting held up because only the executive director or CEO could make them. Joanna Lennon, the founder and CEO of The East Bay Conservation Corps, offered an analogy to plugging holes in a dike with all her fingers and toes, with the rising tide eventually overwhelming her capacity to hold the water at bay.

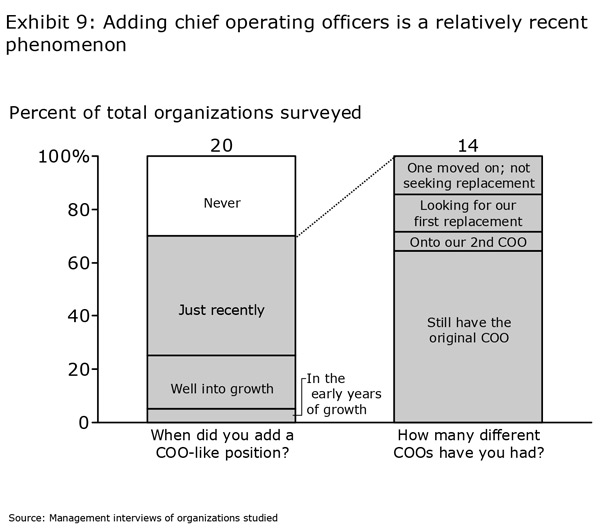

Bringing in a chief operating officer or, alternatively, delegating COO-like responsibilities to a senior staff member, constituted a direct response to the complexity that comes with growth. (As Exhibit 9 shows, the addition of a COO is a relatively recent phenomenon for many of these organizations.)

In talking about the contributions of their COOs, many participants in the study noted the implementation skills they brought with them and their ability to impose order on a disorderly world. When the pairing worked well, the COO could provide a balance to the visionary drive of the leader, producing the combination of inspiration and implementation that the organization needed to succeed. As J.B. Schramm, founder and CEO of College Summit, put it, in retrospect he would have “hired his opposite” three years earlier than he did.

COOs were instrumental in rationalizing programs and thinking about how to get the most impact from the leanest operations. They also had the energy to devote to critical internal functions, such as financial management, monitoring performance, and hiring and training staff, which many stretched-thin leaders had not previously been able to address. Perhaps the most important function the COO fulfilled, however, was freeing the leader from daily operations, so that he or she could fulfill the roles which only they could perform, chief among them fundraising and developing—and maintaining—strong board and external relationships.

In order to benefit from a COO’s skills, the organization had to get over the hurdles of finding the right person and integrating the role. Most of the participants agreed that it was difficult to find the right person for this critical position, and some failed in their attempts the first time around. Several described the dilemma they faced looking for a person with the right management and operational skills who could also fit into the culture. Both Geoff Canada (president and CEO of Harlem Children Zone) and Steve Mariotti (founder and president of NFTE) expressed regret about overriding initial concerns that a key manager or COO hire would not be a good cultural fit. NFTE eventually experienced success with a COO with years of corporate experience and the right personality for the job; Harlem Children’s Zone, and also YouthBuild USA, reached inside for the right candidate, and gained the advantage of someone with deep knowledge of the programs and credibility with other staff. Given the cost of having a COO fail, which often included losing valued staff, these leaders emphasized the value of building in backstops and erring on the side of over-communicating when a new senior manager signs on.

Clarifying the COO role and explicitly dividing responsibilities between the leader and COO could also be a substantial challenge. Many leaders were not only accustomed to being enmeshed in the organizations’ daily work but also had strong relationships with existing staff who were now being asked to report to someone else. Yielding these roles and relationships tended to be hard for everyone. Asked about the devolution of decision-making at Harlem Children’s Zone, Canada said simply, “People’s reactions were what I thought—they hated it.” The fact that the COO’s position was often introduced in concert with new organizational controls, such as measurement metrics and financial management systems, only increased the likelihood that he or she would serve as a kind of lightning rod for resistance to change.

The leaders and COOs we met with identified trust, communication, and ground rules for the roles each would play as critical ingredients for success. As Mia Roberts, COO of Big Sister Association of Greater Boston, observed, “You must be patient… to build trust. People want to… know that you are meeting expectations and that you can deliver and deliver consistently.” In order to allow COOs to “deliver,” however, the leaders had to invest the COO’s role with credibility by visibly yielding decision-making power. “The thing I can’t pay Steve [Mariotti, president and founder] and Mike [Caslin, executive director and CEO] enough respect for,” said Dave Nelson, NFTE’s COO, “is they said, ‘Dave, here are the keys to the car. Just get us where we need to go safely.’”

Identifying and agreeing on signs to assess how the transition was going helped several organizations negotiate it successfully. For example, both Harlem Children’s Zone and Big Sister Association of Greater Boston tested the waters by using what their leaders called the “line test”: how many people were lined up in front of the COO’s door instead of the leader’s. Cognizant of how important the relationships that pre-existed her were, Big Sister Association of Greater Boston COO Mia Roberts commented, “I couldn’t just tell everyone to stop going to Jerry [Martinson]’s [the executive director’s] office. You have to earn people’s respect. Jerry and I agreed that I would not interrupt relationships in a hierarchical way… If people started coming to my door we would know that our job was done.”

Observation 6: The complexity caused by growth gave rise to the need for formal systems and staff with more specialized skills. These, in turn, tended to create internal stress as well as a more professional organization.

To sustain growth, the organizations had to fill a number of management roles besides the COO. They also had to upgrade their systems as defined not only by the technology infrastructure but also by operating policies and procedures that would allow them to work more efficiently and insure them against liabilities (especially in the areas of human resources and finance). James Cleveland, COO of Jumpstart, noted that when he came, “For the most part, Jumpstart had people doing more than they were capable of. We had to simplify. There were systems that had been in place for years that were easy to use if you were managing two sites, but impossible if you were managing eight sites, because you just didn’t have the time.”

The predictability of the specialized knowledge and functional skills a growing organization requires did not make them a whit less crucial. Consider human resources. Hiring was a critically important task in these organizations, given that they were working with youth and were responsible for their safety and well-being. It was also an ongoing process, so hiring (and training) practices needed to be efficient as well as effective. Performance reviews, compensation, and promotion policies also became higher priorities, especially as the organizations increased the number of high-level positions. All this translated into a list of what Youth In Need’s president and CEO Jim Braun calls “nuts and bolts” functions, such as an HR database; pay and benefit consistency; recruiting and hiring; background, credential, and licensing checks; and exit interviews.

Finance was another “invisible” function the organizations needed to upgrade, by adding more sophisticated financial managers and management systems. Similarly with development, adding staff with specialized skills and knowledge was one of the ways in which the organizations met the challenge of increasing and diversifying their sources of funding as they grew. Big Sister Association of Greater Boston hired a development director to rejuvenate board-giving and initiate an individual giving campaign, for example, while Public Allies hired a government relations person as it began to rely increasingly on money from AmeriCorps.

Good information technology was a necessary, and often under-funded, complement to all these functions. It was also essential for monitoring and improving performance. Public Allies offers an example of how technology, above and beyond the basics, can advance an organization’s mission. Its system for tracking participants and participant outcomes has been invaluable in producing transparent data across sites and efficiently satisfying the data needs of the organization’s management and different types of funders. This kind of system, considered a luxury by many nonprofits, is increasingly a necessity and becoming more affordable for rapidly growing organizations.

From the perspective of existing staff, the increased professionalism that accompanied growth could be a plus or a minus. On the one hand, growth could help to curb staff turnover and develop new leaders. Turnover for several of the organizations was a constant challenge. Given the intensity of the work and the typically low pay, young people made attractive hires. The same reasons—coupled with life-stage events and general mobility—sometimes led to situations in which employees routinely departed after one or two years.

For many of these organizations, growth created the need for new, more responsible middle-management jobs. Big Sister Association of Greater Boston described the process: “We needed to introduce a middle layer, and we also needed to develop talent. Two of our managers now were internally grown. They started as social workers six years ago. We developed that talent so they could stay here. We now have an explicit training program.”

Organizations with a national presence had the added benefit of offering multiple geographies within which its employees could work. As talented staff progressed, they could recruit (and groom) new staff to fill more junior positions. Summer Search focuses on attracting talented young people and giving them leadership opportunities. Citizen Schools explained that, “It’s easy to dissipate the core as you grow, but we decided to reinvest in [it]. This has allowed us to keep great people and attract great people.”

On the other hand, these organizational changes could also take a high toll on existing staff. Some employees were not willing to stay with the organizations as they became more standardized and structured. Often there was a disconnect between senior management’s interest in growth and others’ interest in maintaining the current size. As one founder commented, “though everyone [in the organization] is imbued with the mission, they are not imbued with the growth plan.”

Change could be especially painful when existing employees did not have the skills and capabilities required to meet the organization’s evolving needs. Several participants talked about the difficulty of finding new roles for such individuals and the hard task of transitioning out champions who were among the longest serving and most loyal members of the staff. They also discussed the challenges they had faced in developing the managerial skills required to guide larger, more complex organizations. In one instance, the board had provided formal coaching for its executive director as well as access to an executive education program. In other cases, helpful advice and informal coaching came from individual board members or trusted consultants.

At times, however, growth ultimately did require the leader to change roles, relinquish control, or even leave. When the leader was also the founder, this transition could be especially difficult; but if the organization handled it gracefully it could also set a powerful example. Linda Mornell, founder of Summer Search, says, “It’s one of the things I’m proudest of as a founder—I’ve let go.” Jumpstart also had a solid method for transitioning the founder. According to former Jumpstart board chair Jeff Bradach, “The thing that’s remarkable is that [the founder] genuinely stepped away and created space for [the new CEO]. And [the CEO] very smartly would engage [the founder].” However, other organizations struggled through this transition. One founder commented, “There are times in the last year when I’ve asked myself if I should step down.” And though it is not an easy conversation to have, within many organizations staff spoke about both their pride in what the founders had created and their worry that these same people might not be the right ones to manage the organizations in their larger states.

Observation 7: Growth almost always required redefining the role of the board and its members.

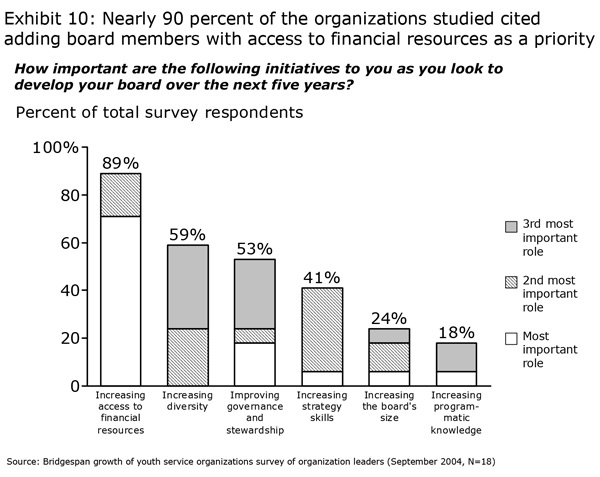

Growth often affected the boards of these organizations as profoundly as it did the staff. At virtually all of these organizations the board was moving (or had already moved) away from a hands-on programmatic role to one that emphasized fundraising and governance. (Exhibit 10 shows the initiatives these leaders expect their boards will be most engaged with over the next five years.)

At times, these transitions required changes in the board’s membership as well as its responsibilities. Managing these changes gracefully was challenging (and time-consuming) for everyone concerned—especially the leader. One of the keys was to be transparent about the expectations for new members and the value they could bring. For example, when NFTE founder and president Steve Mariotti looked at the ability of successful fundraising nonprofits like universities, it became clear to him that capital was critical to NFTE’s plan to reach more students: “During Harvard’s campaign, Neil Rudenstein raised $2 million per day. Capital per kid is what matters.” Mariotti envisioned a capital campaign that would allow all the organization’s overhead expenses to be paid for, so that any additional funding would go directly to program expenses, and set out to recruit new board members. Mariotti tried a novel approach to impress upon the prospective board members how much NFTE would value their time and energy: “I went out to recruit the ‘Seven Samurai’ for our board, and I said to them, ‘We’re getting ready for you. We’re not ready yet. But we’re getting ready, and in a year, I will be back.’” Mariotti returned over the next several years, all the recruits accepted, and NFTE’s capital campaign is successfully underway.

Not all of the organizations experienced radical board change. Some boards went through incremental changes, which included explicit conversations with members about new and more ambitious fundraising expectations as well as wider roles in fiscal oversight and periodic strategy reviews. Big Sister Association of Greater Boston, for example, asked board members to double their financial commitments and give early in the year to help with financial planning and to inspire others to give. The board, which supported Big Sister’s goal of reaching more girls, responded affirmatively.

The Steppingstone Foundation and The East Bay Conservation Corps offer examples of the value that can come from evolving the role of the board. Both organizations began with boards of friends, people who supported the founders personally, as well as what they were trying to do. The EBCC board actually underwent two transformations: first to a group of influential people who lent their names more than their time or money, and then to a board that was more involved, especially in fundraising. At Steppingstone, the transition was more subtle. The shift in the role of the board was due to a new chair, the first board member whose introduction to the organization was not as a friend or acquaintance of founder Michael Danziger, but via his own passion for the issues Steppingstone addresses. As a result, the board has begun to impose more discipline on itself, creating more task-specific committees and roles, and to demand more accountability from Steppingstone as well. Both founders, Joanna Lennon and Michael Danziger, agree that the additional discipline has been positive for their organizations, and a welcome balance to their own passions and opinions.

The Chutes and Ladders of Growth

Our last observations focus on several factors that appear to have aided or impeded growth. The three that came up most often in the interviews were the influence of foundations, the importance of performance measurement, and the scarcity of funds for investments in infrastructure.

Observation 8: Foundation funds could propel growth, but they were unlikely to sustain it.

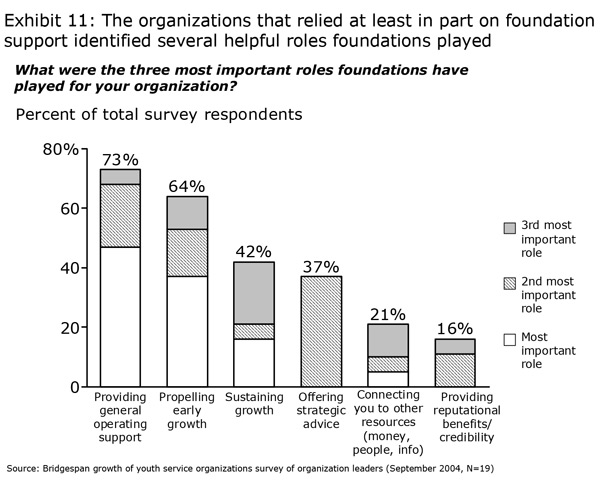

Foundations played a variety of roles in the growth of the organizations in this study. (Exhibit 11 shows the kinds of assistance leaders of organizations that receive foundation support found most helpful.) The most common, and most important, roles were propelling early growth and providing general operating support. Citizen Schools, College Summit, Earth Force, and Public Allies relied heavily (if not exclusively) on foundations for their initial growth. The EBCC, Harlem Children’s Zone, and YouthBuild USA received foundation funds at critical junctures in their organizational lives.

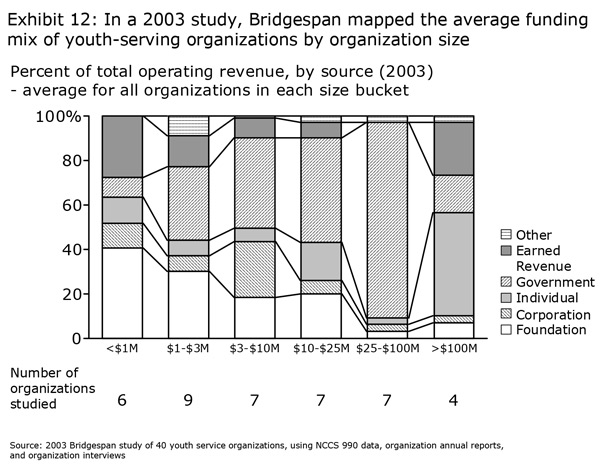

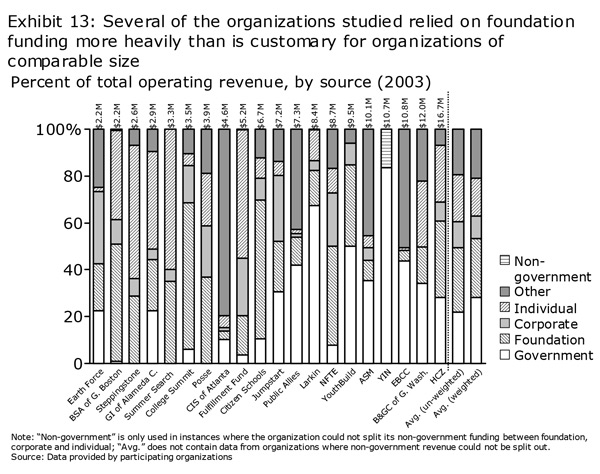

In a 2003 study of the funding mix of 40 youth-serving organizations, Bridgespan found that foundation funding, on average, fell from roughly 40 percent of total revenue, when a youth-serving organization was under $1 million in size, to less than 20 percent, when it was in the $3-to-10-million range. (See Exhibit 12.) While the organizations in the study conformed to this general pattern (see Exhibit 13), several (including College Summit, Posse, Citizen Schools, NFTE, and Harlem Children’s Zone) received a significantly higher proportion of overall funding from foundations than is customary for organizations of comparable size. For example, Citizen Schools, which has an overall budget of just under $7 million, receives more than 50 percent of its funding from foundations, while roughly one-third of NFTE’s nearly $9 million comes from foundation funders.

Crucial as this support was, the leaders of these organizations also recognized the importance of building a more diverse revenue base. Citizen Schools’ president and co-founder Eric Schwarz has been working for several years to identify new supporters who can help cover the added costs of new sites. “For individuals you have to invest in the cultivation of people. Building a strong board and staff is key to raising more money from individuals. For the public sector, you need a talented person who can write great grants and do great research. You also need someone who can network. In the corporate world, a different type of networking is important. Conferences help build respect. There is no silver bullet. We aim to build a range of revenue flows, each of which covers 10 percent to 15 percent of the budget.”

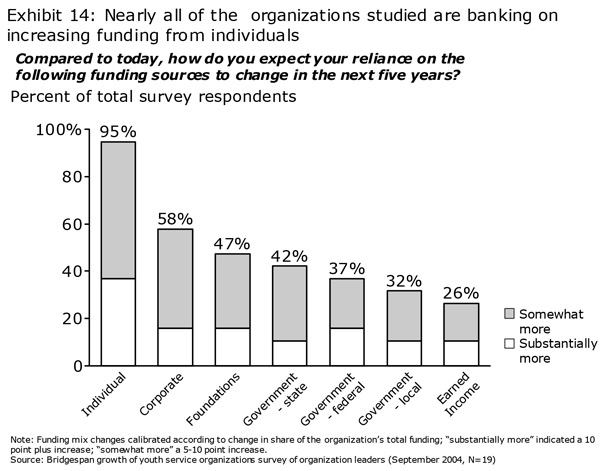

Schwarz was not alone in targeting individual donors as a potential source of increased funding. Every organization in the study expects to increase the percentage of its revenue coming from individuals over the next five years. (See Exhibit 14.) One of the primary reasons cited for this emphasis is the data that suggest a massive transfer of wealth to the sector in the future. Among the steps these organizations are taking to try to tap this pool are increased hiring of development staff and recruiting heavy hitters onto their boards. How successful these efforts will be remains to be seen.

Observation 9: These organizations believe codification was essential in enabling them to expand without sacrificing quality.

Study participants struggled with questions about how much variation and program experimentation was healthy and at what point it impinged on the results they were trying to achieve. Ultimately, however, all of the organizations found that in order to expand successfully, they needed some degree of program codification. A number of factors drove in the direction of codification. One was the desire to ensure that the organization continued to have the same impact on all its participants. Another was a sense of responsibility to colleagues, to share wisdom gained from experience. Dorothy Stoneman, YouthBuild USA founder and president, pointed out that, “It doesn’t work to just throw an idea at local organizations. We know so much about how to do it; our role is to tell them what we know to date about how to implement it effectively. Then they can build on what we’ve learned and do it even better.”

For some organizations, like Posse, which aims to change diversity and leadership on college campuses, altering the way that the world around them thinks or operates is core to their mission. As a result, fostering a consistent culture in new locations is as important to the success of their programs as codifying the procedures that make these programs work. Posse focused on documentation from the outset, creating its first program manual to codify the work of the original New York site before the second site even opened. Equally important, it developed extensive training and acculturation processes, and stipulated elements (such as the appearance of the site) to reinforce the culture and common values.

The appropriate degree of codification and adherence to specific processes for an organization depended on its objectives. For example, Communities In Schools of Atlanta’s priority is using community resources to improve students’ lives. Therefore, they were more concerned with specifying the outcomes of their program than with specifying the program strategies per se, which had to be able to accommodate each school’s needs, students, and community dynamics. As executive director Patty Pflum observed, “There is no single manual for going into communities and helping them improve their schools. The key is to find out where the obstacles are and where the resources are.” The balance to this flexibility is provided by the field supervisors, who ensure that every school has a site plan (developed by the program person with the school’s principal) with clearly identified benchmarks.

Whatever the form codification took, it represented a significant investment of time and energy on the part of the organization. Further, it was not something that could be done once, put on a shelf, and then simply taken down from time to time. If manuals or processes were to be effective, they had to be revisited in light of local conditions and innovations in the field. For example, Posse hired two people to write its original program manual and is in the process of revising it today.

The process of codification went hand-in-hand with evaluation. Ensuring that a program is making a difference to its participants was the most compelling reason to measure outcomes. But measurement filled other functions as well, including establishing credibility with funders and allowing the organization to monitor outcomes and therefore establish arms-length accountability.

Observation 10: The later an organization made performance measurement part of its culture, the more disruptive the process was.

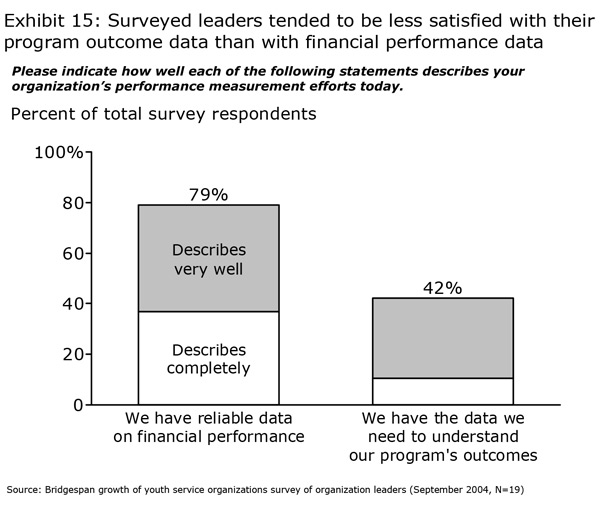

All the organizations were collecting some sort of performance data. However, the sophistication of the data and the degree to which the use of data had been internalized and incorporated into decision-making varied considerably. For example, the level of confidence among the participants that they had reliable data about their organizations’ financial performance was high. But only half as many participants were equally confident they had the data they needed to know whether their programs were achieving the desired outcomes. (See Exhibit 15.)

The influence of funders in getting people focused on performance measurement was unmistakable. Even if it is not yet true that, as one leader stated, “Every funder is looking for evaluations and outcomes,” the perception that this is the case was widely shared. As Michael Danziger, president and founder of The Steppingstone Foundation, commented, the “anecdotal stuff” is not compelling. Jerry Martinson, the executive director of Big Sister Association of Greater Boston, reported that, “Every funder is looking for evaluations and outcomes… People want to know what difference did [a program] make, what impact did it have? To be able to take a proven validation, [to show] that it works is extremely useful… It shapes how we do business and it shapes how we talk to people.” These examples could be repeated for almost every one of the organizations.

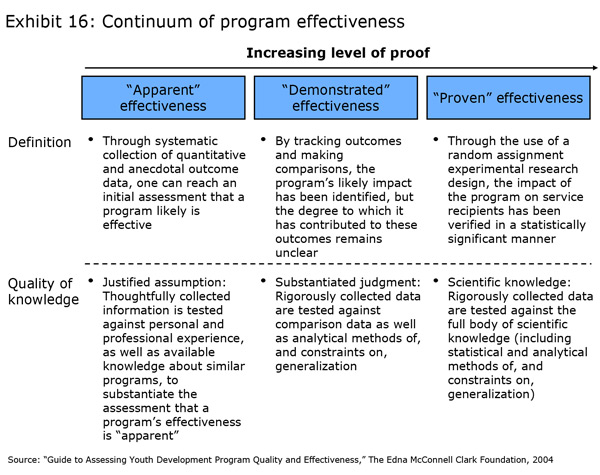

The organizations in this study appear, on balance, to have established a higher level of proof of outcomes than the average. David Hunter of the Edna McConnell Clark Foundation has developed a continuum that can be used to assess the level of evidence an organization has for the effectiveness of its program or programs: apparent effectiveness, demonstrated effectiveness, and proven effectiveness. (See Exhibit 16.) Hunter reports that “most youth development service providers offer programs that fall somewhere in the range of ‘apparent effectiveness.’”[8] Of the 20 organizations in the study, 13 report practices that would put them at the high end of apparent effectiveness, six can be categorized under demonstrated effectiveness, and one has met the lower end of the proven effectiveness criteria.

Several of the leaders expressed regret that they had not begun collecting and aggregating performance data earlier in their organizations’ existence. One, looking back, offered the following advice: “Set your priorities and start accumulating data for your outcomes.” At the same time, the most valuable aspect of collecting performance data for this leader (as for others) was the insight it provided for the organization. “The true value of who we are really started [to become apparent] when we could track who the kids are and where they were going.”

As this comment indicates, the value of collecting and monitoring performance data sooner rather than later in an organization’s life went well beyond having the capacity to respond to funders’ requests. A number of organizations, including Earth Force, Jumpstart, and The Steppingstone Foundation, introduced performance measurement so early that it seemed to be part of their DNA. As a result, they not only had measures “before anyone else was asking for them,” in the words of Steppingstone’s Danziger, but also seemed to have an easier time integrating data into their decision-making as the organization grew.

When Jumpstart began implementing a new regional management structure, for example, program directors caught on remarkably quickly to the idea that, in Rob Waldron’s words, “You can’t manage remotely unless you have information in front of you, and using indicators to really drive decisions [is] key to your success.” Jumpstart’s leadership also realized that the risk of moving to a less tightly controlled—and faster-growing—network wasn’t going to be an issue when they saw performance data indicating that affiliates were out-performing company-owned sites.

In contrast, organizations that came late to performance measurement tended to find it organizationally taxing and at times divisive. Even when management had internalized the value of the new practices, program staff tended to be skeptical, viewing them as bureaucratic at best and antithetical to delivering quality services at worst. As one leader told us, “These people are all passionate about the growth of the kids, and so they picture their work as one kid at a time… [Tracking outcomes is hard] because our staff really feels this as a pull away from the work that they do… They feel like it’s different from serving the kids.” These comments were echoed by another leader, who was also in the process of instituting performance measures: “Funders as well as the people we are serving are demanding to see the outcomes of our service. Not everyone who works here feels the same way about this. Shifting the mindset of people has not been easy.”

Introducing data collection and performance evaluation into an organization that has operated without them requires significant investment, not just of money, but also of management time. As Harlem Children’s Zone’s Geoffrey Canada noted, “If you’re going to live with metrics… to get to that place takes time, much longer than we ever thought… I honestly had no idea.” Building internal evaluation capacity by working with program staff and aligning it with their needs was one successful approach. For example, Earth Force has a full-time director of education who works with the sites and their external evaluator, Brandeis University, in addition to his responsibilities for training and program design. YouthBuild USA has a staff member dedicated to data collection who is as much an advocate for the value of data and coach to the many field sites as she is an analyst.

Nancy Wachs, the executive director of After School Matters, is very clear that the young organization she leads needs “more proof and fewer anecdotes.” To address this need, in 2003 she brought on a director of research and evaluation whose first project was to rebuild the organization’s existing database, so that they could track the kids from semester-to-semester. Now they are engaged in a strategic planning process to determine the outcomes data ASM will need to prove their model. Wachs realizes that they also need “a longitudinal study with control groups, to figure out what happens to kids after the program.” But she estimates that such a study would cost more than $1 million, and knows that “people on our board are shocked by how much it would cost.”

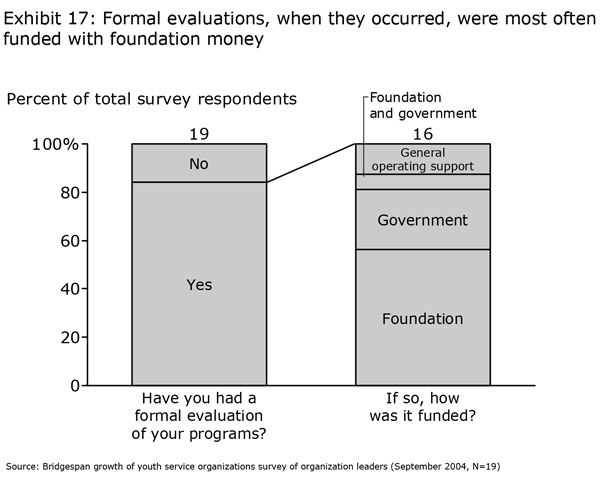

As Wachs’s comments indicate, finding the money to support formal evaluations was a challenge. Canada framed the dilemma succinctly: “If you don’t have the evaluation you can’t get the big money, but if you don’t have any big money you can’t do the evaluation.” Of the organizations whose programs have been formally evaluated, only two paid for the evaluations themselves, while the rest relied on foundations or government agencies (see Exhibit 17).

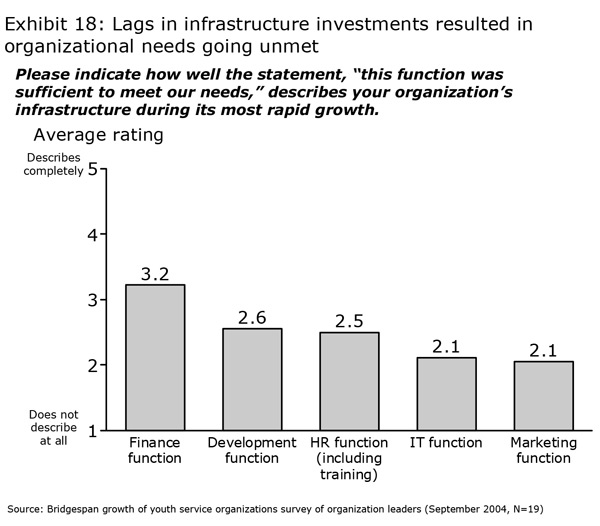

Observation 11: Funds for building infrastructure consistently lagged the need for them.

Without exception, the organizations we interviewed credited much of their success in sustaining growth to the addition of key positions (and the remarkable people who filled them) as well as to the introduction of critical systems for managing functions such as finance, development, human resources, and information technology. As the former COO of The East Bay Conservation Corps, Janice Jensen, commented, “You add the non-program people last, out of necessity. But in order to have strong programs, you eventually need strong infrastructure. Not bloated, but strong.” Funds to build this infrastructure consistently lagged the need for them, however. Vince Meldrum, the president of Earth Force, reflected the experience of his peers, when he pointed out that “general operating, accounting, and administration—in other words, all the infrastructure—is the hardest thing to get funding for.”

The data summarized in Exhibit 18 show how the absence of funds for infrastructure investments adversely affected key management functions. But the strains and stresses this data represent cannot be conveyed by numbers alone. Consider the experience of Communities In Schools of Atlanta, which added 21 new people to its existing 14-member program staff when it took on Project GRAD in 2000, without a commensurate expansion of the management team. Four years later, training, systems and policies for integrating new staff had yet to be fully developed and codified. Almost 60 percent of the staff had two years or less of experience with the organization. Similarly, according to Dawn Hutchison, vice president of marketing and development for Public Allies, growth often felt “like building a house before building the foundation. Growth was driven by demand and when funding was available for growth. However, you need to balance the drive for growth with the capacity needed to support new sites effectively. Now that we are twelve years old, we are just coming into adolescence as an organization with the necessary management and support systems.”

Organizations in the study coped with the scarcity of infrastructure funding in two primary ways. Those that relied heavily on government grants, which include an allowance for indirect costs, typically took a “build-as-you-go” approach. While such allowances seldom covered all the people and systems an organization needed, they did allow for relatively steady, incremental growth. Youth In Need, for example, did not begin to add essential administrative roles until 1998, when the organization began to participate in Head Start. President and CEO Jim Braun who was accustomed to being “the CFO, the HR director, calling the shots on when to get an attorney, [writing] all the funding reports, [and doing] all the donor development,” began by hiring a senior vice president of finance. He was joined in subsequent years by a human-resources staff person and a chief development officer; although even then, Braun recalled, “I wanted the donor development person for years before I was able to get it.”

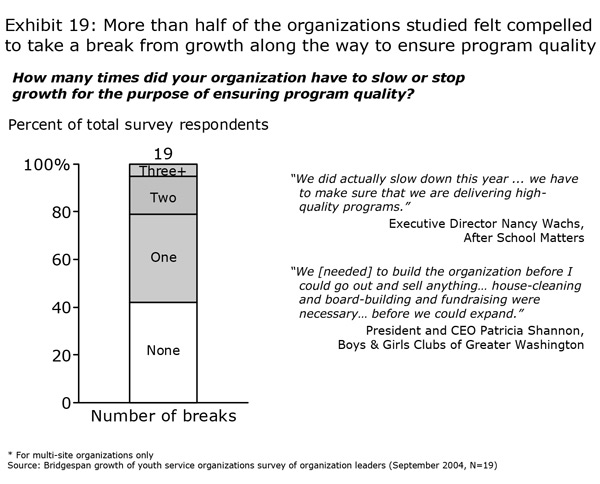

For most organizations, building infrastructure was a never-ending process of catch-up. And more than half had to put growth on hold so that they could put essential personnel and systems in place. (Exhibit 19 shows the number of times organizations in the study had to take a break from growth to ensure the quality of their programs.)

Pat Shannon’s experience at Boys & Girls Club of Greater Washington gives a taste of what that experience could be like. When Shannon joined the organization in 1995 as president and CEO, the board mandated growth in four geographic areas where there was a pressing need for services. But Shannon felt strongly that growth had to be put on hold in order to address issues that ranged from cash flow and fundraising to risk management, the need for key program and management hires, and—most importantly—the quality and consistency of the clubs. The organization paused and shored up its finances, procedures, systems, programs, facilities, and staff, and “now has a number of people in the right positions doing the right things at the right time.” Nevertheless, it is once again in need of “more sophisticated resources at the management level,” following a merger that increased the number of children served from 15,000 to over 35,000 annually.

The benefits of being able to add management capacity before its absence creates a crisis are evident in the recent experience of Harlem Children’s Zone. Due in large part to funding from the Edna McConnell Clark Foundation, HCZ was able to fill some critical leadership roles in anticipation of the needs they saw close on the horizon. The HCZ story illustrates the value of hiring ahead of the need. According to president and CEO Geoff Canada, “We were able to then grow with all the systems and stuff in place and people chomping at the bit. It kept us ahead of the curve.” The pace of their subsequent growth testifies to the value such an approach can have.

Concluding Thoughts

Growth is a roller coaster for every organization, whatever its tax status. But the ride can be especially tumultuous for leaders of nonprofits because, unlike in the for-profit sector, growth is seldom rewarded by greater ease in attracting new resources. As one of the participants in our growth study remarked, only partly in jest, “Why would you grow in an environment that just creates more risks as you grow?”

Against this backdrop, it is especially heartening to find organizations, including those that participated in this study, that have successfully navigated the “chutes and ladders” of growth. Their achievements are noteworthy, and their collective experiences offer a powerful body of knowledge for the leaders of other nonprofits that may be contemplating growth as well as for those organizations, like the Edna McConnell Clark Foundation and the Bridgespan Group, that support such efforts. At the same time, these success stories—even more than any examination of organizations that have not survived—drive home the need for significant changes in the ways in which growth takes place in the nonprofit sector and the potential that could be unlocked by making changes.

We undertook this study with relatively modest hopes: we wanted to develop a rich set of data to help us better understand the growth experiences of a select group of youth-serving nonprofits. On this dimension, we believe the value of the study speaks for itself. Together, this white paper and the 20 individual case studies that lie behind it provide an extensive look at the experience and effects of growth on such organizations.

At the same time, we are well aware that this work is only the first step toward a more comprehensive understanding of growth. So at this point, rather than summarize what has already been said in the preceding pages, we would like to close with some questions and observations that might help to inform the efforts of others going forward. In so doing, we have drawn on both the contents of the study and the experiences of our two organizations in helping nonprofit organizations expand the reach of their services.

Which organizations are candidates for growth?

An obvious but useful reminder is that growth is not for every organization. Often small is beautiful, and there are many good programs whose virtue lies precisely in their being small. Further, there are many organizations that want to grow but are not yet ready to do so. At a minimum, premature growth can lead to limited resources being expended for naught; at the extreme, it can put the entire organization’s existence on the line.

For these reasons, we believe it is crucial for all parties involved in the decision to grow a nonprofit to have a clear-eyed view on whether the staff and board of the organization are both willing and able to take on the challenges growth will bring. Force-feeding growth to an organization unprepared for it—or resistant to it—is a mistake from every perspective. This makes it especially important that we continue to advance our understanding of the factors that need to be in place before significant growth occurs. In our minds, one of the most critical unanswered questions is: what level of evidence of programmatic success a nonprofit ought to be able to demonstrate to justify investing in its growth? Similarly, how much organizational capacity (in the form of management skills, internal systems, and leadership and governance structures) is required to undertake growth, and what can be added along the way or after the fact?

How can funders trying to support growing organizations be most helpful?

Definitive answers to this question would be premature given the limits of our experience and research to date. However, the study does suggest a few possibilities that might be useful for funders interested in supporting growing organizations.

We begin, not surprisingly, with the proposition that planning matters. Supporting the development of a thoughtful growth plan can help an organization’s leaders clarify its strategic objectives and direction, and make it easier for them to differentiate opportunities worth pursuing from those more likely to threaten the mission. The planning process can also help bring an organization’s board and staff into alignment and foster strategic thinking among a larger set of its management team. Such perspective is especially useful to funders, as well, when they choose to place relatively big bets on a small number of grantees, as the Edna McConnell Clark Foundation has done. Both of our organizations have pursued planning activities with nonprofit organizations to good effect.

Second, providing sufficient funds to either bolster or put in place missing, but essential, functions or capacities is not just helpful but critical for improving the chances of success. Whereas it was comparatively easy for the organizations studied to find funds for new programs, all of them struggled to obtain support for infrastructure—the people and systems that would enable them to deliver those programs effectively. The success of Harlem Children’s Zone, for example, suggests the value that can be created by helping nonprofits to build capabilities before their absence throws the organization into crisis. Providing such funding in a sufficient amount, either as unrestricted general operating support or flexible multi-year commitments, gives an organization’s leadership a running start and increases the likelihood that their efforts will be successful.

Pooling capital with other funders and encouraging joint reporting is another potential way to improve support. Responding to multiple funders’ requests for information and satisfying their specific needs can distract organizations from their core objectives and impose a heavy burden on management’s time. Similarly, by cooperating to support a single growth plan, individual funders could help organizations avoid these additional hurdles and extra work that diverts them from delivering quality services to more young people in need.

Last but not least, there is ample room for funders to support youth-serving organizations with resources other than money, for example: coaching and mentoring executive directors and other managers so they can better deal with the stresses and challenges that accompany growth; aiding organizations with board development and strategy; helping with the creation of measurement systems and program codification; and providing other forms of capital, such as loans and program-related investments. There is also real potential for funders to make a difference by helping to professionalize the field of youth-service management, which lacks many of the support systems of other professions (such as teaching, firefighting, and medicine) that society finds essential. Such efforts could include creating and sustaining educational and training programs, professional associations, and periodicals as well as providing help from search experts, technology specialists, and other professionals.

How can the flow of funds to proven programs be increased?

Growth increases an organization’s need for funds, but it rarely opens new doors for obtaining them. Unlike in the for-profit sector, growth in the nonprofit sector is seldom rewarded by greater ease in attracting new money. In fact, an established track record and proven results can be serious impediments to raising funds, because philanthropists tend to gravitate to what’s new and different rather than what’s tried and true.

Supporting new ideas, institutions, and social movements has been—and continues to be—an essential part of philanthropy’s purpose. However, an equally compelling case can be made for greater philanthropic support for programs and organizations that have demonstrated their ability to deliver results for participants. In principle, one might argue that investing in well-established organizations and existing service models could slow the development of new ideas. In reality, both current grant-making practices and the experience of the organizations in the study lead us to believe that the pendulum has swung too far toward novelty.

From our perspective, there is an urgent—and growing—need to find ways to help established organizations expand their programs so they can have a far greater impact on society’s challenges. With budgetary pressures on state and federal government spending intensifying, it is increasingly hard to see where the funds to expand effective social-service programs will come from. But that said, government remains the dominant source of funding for programs affecting the lives of youth. We must find ways to ensure that government funding is better aimed at supporting programs with demonstrated effectiveness and to increase the odds that the organizations that deliver those programs are able to attract the support they need to scale up.

For the Edna McConnell Clark Foundation and a number of other funders, the most logical response to the current youth-services landscape has been to focus on larger, longer-term investments in proven programs. Given the depth and breadth of the problems so many of our society’s young people are facing, investing in organizations that have demonstrated results, rather than engaging in serial innovation in hopes of finding some untried silver bullet, makes enormous sense. Maintaining a robust civil society does not have to preclude building organizations that can provide kids with services that will help them change their lives. We hope that by conveying the lessons from these studies of growth in action, this paper will help to inform the choices made by other organizations and funders in ways that increase our collective ability to serve youth in need.

Acknowledgement