Summary

Jumpstart has grown by honing its core program model, rather than by adding new programs. The organization has seen considerable change in its first decade in existence, evolving from a branch model to a licensee structure, and transitioning leadership from its founder to a new CEO. Government and foundation funding have fueled expansion, and a strong commitment to tracking metrics has allowed the organization to demonstrate and ensure program quality.

Organizational Snapshot

Organization: Jumpstart

Year founded: 1993

Headquarters: Boston, Massachusetts

Mission: “To engage young people in service to work toward the day every child in America enters school prepared to succeed.”

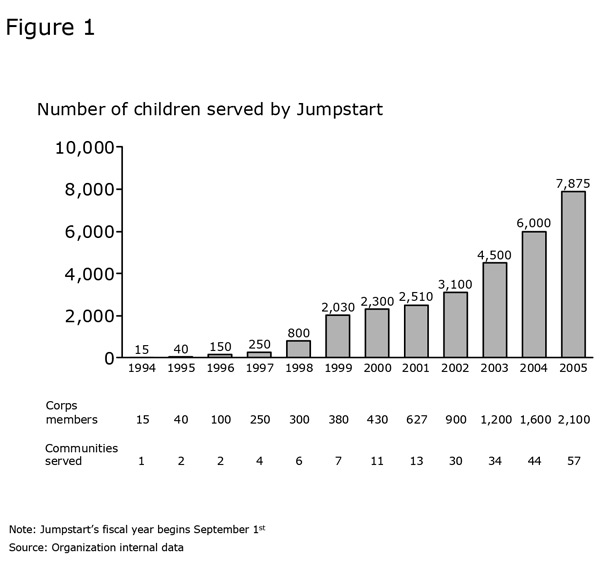

Program: Jumpstart connects two important national trends: the need for quality early childhood programs and the national service movement on college campuses. Jumpstart recruits, trains, and supervises college students to work one-on-one with the five percent of preschoolers who are struggling the most in Head Start and other early childhood programs in low-income neighborhoods. The organization’s goals are to ensure that children are ready to start school; that families are involved in their children’s learning; and that college students are inspired to become future teachers. In the 2005 fiscal year, Jumpstart will serve nearly 7,900 children in 57 communities across the country. Approximately 2,100 college students are participating in Jumpstart at 66 higher education campuses. Corps members hold twice-weekly, two-hour Jumpstart sessions, which involve structured classroom time following the traditional school day. Each Corps member spends additional time in classrooms supporting teachers. During Jumpstart Summer, Corps members team-teach children full-time with a mentor.

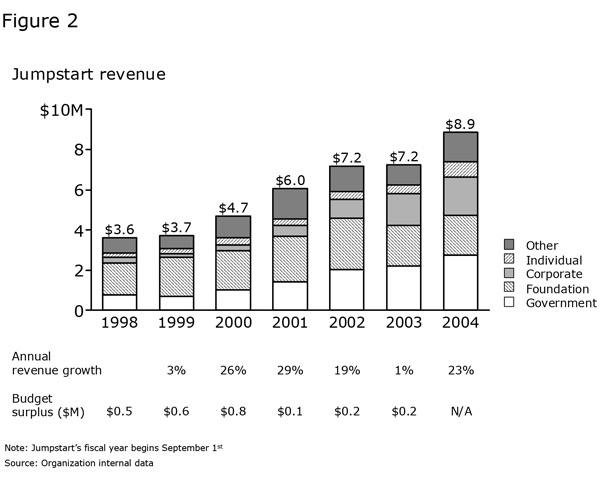

Size: $7.2 million in revenue; 51 employees[1] (as of 2003).

Revenue growth rate: Compound annual growth rate (1999-2003): 18 percent; highest annual growth rate (1999-2003): 29 percent in 2001.

Funding sources: As of 2003, government, foundation, and corporate funding were Jumpstart’s top sources of revenue, accounting for 30 percent, 28 percent, and 22 percent of funding, respectively. Jumpstart collects government revenue from such programs as AmeriCorps, the federal Work-Study program, and Head Start, which it then disseminates to its affiliates. Gifts-in-kind and individual donations account for the majority of the remaining funding.

Organizational structure: Jumpstart’s network includes five branches that operate under Jumpstart national’s 501(c)(3) and 52 sites run by universities and colleges that license the Jumpstart program model. Licensees are the current priority. Five regional offices manage the network (Northeast Region in Boston; Mid-Atlantic Region in New York; Central Region in Chicago; Southern Region in New Orleans; and Western Region in San Francisco).

Leadership: Rob Waldron, president and CEO; five regional directors.

More information: www.jstart.org

Key Milestones

- 1993: Founded in New Haven

- 1994: Expanded to Boston

- 1996: Secured AmeriCorps funding

- 1997: Expanded to New York and Washington D.C., with headquarters in Boston

- 1999: Transitioned from branch to licensee model

- 2000: Developed strategic growth plan with consulting support from New Profit, Inc. and Monitor

- 2002: Hired Rob Waldron as president and CEO

Growth Story

Jumpstart’s origins trace back to a summer in the early 1990s, when a Yale undergraduate, Aaron Lieberman, returned home from tutoring underprivileged kids in an upstate New York camp. He knew from his mother, the director of a regional teacher-training center for the federal Head Start preschool program, that about 50 percent of all children from low-income families start first grade with preschool skills that lag their peers by up to two years. These early inequalities persist and increase with time.

Jumpstart was born in 1993, when Lieberman enlisted his classmate Rebecca Weintraub as a co-leader, rounded up 15 fellow students, and convinced the New Haven Head Start program to let his fledgling organization tutor kids one-on-one. The organization’s early growth was opportunistic, primarily following the moves of the cofounders to new cities. The organization expanded to Boston in 1994, with Lieberman serving as chief executive officer after he graduated from college. In 1996, the organization secured AmeriCorps funding, which gave participating college students a grant they could use toward their education. In 1997, Jumpstart opened branches in New York and Washington, D.C., with a national headquarters in Boston. By then it had expanded into summer tutoring at all its locations. National attention came when First Lady Hillary Clinton personally joined the organization to celebrate its 1,000th summer student. See Figure 1 for details of the organization’s expansion.

Jumpstart’s growth got a boost from federal rules that allowed nonprofit organizations to use federal Work-Study and AmeriCorps funds for national service. The organization’s model of universities licensing Jumpstart’s program and overseeing local Jumpstart sites grew out of this change.

Jumpstart signed on San Francisco State University and UCLA as its first licensees in 1998. It expanded to colleges in New York, Pennsylvania, Arizona, Minnesota, and elsewhere in California, as colleges expressed interest. “At first, you’ll just go anywhere,” says CEO Rob Waldron. “It’s like being asked to the prom. You’re just so glad to have been asked.”

In 2000, Jumpstart began to manage its growth more strategically, with the help of business planning from venture-philanthropy group New Profit Inc. and the Monitor Consulting company. The new business plan called for the Jumpstart network to grow to more than 50 sites over five years, with a capacity to serve 16,000 children in 2005. The growth would follow criteria for evaluating future university partners, including sufficient Work-Study and university funding, number of undergraduates, fit with the community, campus culture of service, and viability and need in the community.

Jumpstart’s management team now looks at universities more selectively, with proximity to the regional base being an important consideration. The advantages of greater proximity are greater face-to-face contact and the ability to aggregate regional fixed costs. Jumpstart will now reject an application that is not strong enough, such as those that fail to show how they’d support a program or why the program would be viable. Jumpstart estimates that it can bring on 10 to 20 new sites per year, with each region being able to support three to four new additions, depending on the leadership available in that region.

The organization is now focused on serving as many kids as it can at each site, as a way of growing efficiently. “The choice to get more mileage out of each site was very deliberate and considered, and has been critical in expanding the number of beneficiaries at less cost,” says a former board member. Jumpstart is also disciplined about turning away money that doesn’t fit with its mission. An electronics company approached Waldron to invest in increasing math skills, but Waldron turned down the money because of Jumpstart’s focus on literacy.

But this new strategy also came with its own growing pains for the organization. In 2002, Jumpstart transitioned leadership from founder Lieberman to Rob Waldron. Lieberman had reached his limit managing the organization’s rapid growth, and Rob was brought to Jumpstart with the explicit charge of helping replicate the Jumpstart model nationally.

“Early childhood education has moved from a ‘solution problem’ to a ‘distribution problem,’” says Waldron. “We have moved from solving the problem of how to help kids to the problem of how to help more kids. There just aren’t enough caring adults intervening with these kids.”

Evaluation is an integral part of the Jumpstart model. In 2001, Jumpstart developed the School Success Checklist, which it uses to assess each child twice a year. The checklist is a 10-item assessment of language, literacy, social, and initiative skills. This pre- and post-assessment process allows Jumpstart to track a child’s progress, measure program impact, and improve content and delivery. Assessments from the 2002-2003 school year show a significant impact on the participating children’s language, social, and adaptive skills. Jumpstart children begin the school year with skills rated lower than their peers, but make statistically significant progress, greater than their peers, in language and literacy, social, and initiative skill areas by the end of the year.

Configuration

At the start of its 2005 fiscal year, Jumpstart was working with 66 universities and colleges in 57 unique communities. These programs are structured as separate legal entities under the auspices of the colleges and universities. Jumpstart provides ongoing technical assistance, training, and monitoring for both the programmatic and financial aspects of the program to ensure high quality and results.

Jumpstart’s governance structure evolved through several major iterations over its life. The organization began with a branch structure in which the Jumpstart national office governed local sites — all of which operated under Jumpstart’s 501(c)(3) — and directed the local programs. The four Jumpstart-owned branches enjoyed a high level of autonomy. Each had its own advisory board, and was responsible for fundraising, program delivery, recruitment, training, and management. The branches paid a fee to headquarters and received startup funding, training, and back-office services. Jumpstart’s national office monitored all aspects of site performance and had ultimate fiscal, administrative, and program accountability.

But the administrative burden of supporting, operating, and funding the new sites became unmanageable as the organization grew. In addition, Jumpstart-owned sites were an amalgam of volunteers from multiple colleges in the area, which complicated operations.

In 1999, Jumpstart transitioned to its current licensee model. The licensee model had the advantage that it was more scalable, because it leveraged universities’ existing fixed-cost infrastructure and financial resources. In return for financial and logistical support, universities receive: support from Jumpstart in the first year of their program through a one-time startup grant of $20,000; twice-a-year leadership conferences; assistance navigating AmeriCorps rules and regulations; and performance measurement systems to help manage the program. Curriculum across all Jumpstart sites is identical.

Jumpstart programs require a significant commitment from a university partner. Jumpstart provides these licensees with both private and federal funding streams to help piece together the $200,000 average annual cost needed to run the program. In instances where AmeriCorps funds are not available, universities successfully have raised approximately 15 percent of the cost of the program. Universities use existing Work Study funds, often as much as $100,000 per institution, to pay Corps members and to fund infrastructure and staff. After the first year, licensees pay a $5,000 annual fee to Jumpstart.

A key component of Jumpstart’s relationships with licensees is a site-monitoring evaluation performed by site staff twice per year and by national staff annually. These metrics have been a critical component of Jumpstart’s ability to give up direct operational control over individual sites. Consistent good-to-high levels of performance on the evaluation enables sites to be promoted to higher levels of Jumpstart affiliation.

Jumpstart uses its Site Management and Monitoring Tool to rate licensees in the areas of management, program, development, and finance. Jumpstart’s Managing by Information system adds another layer of measurement, providing summary metrics for site managers, headquarters, and the board.

The site-level metrics appear to be working well, but the organizational metrics still need some fine-tuning. “One problem is that Jumpstart’s management system of ongoing reporting of site results doesn’t tie in with assessments, which are only done once at the beginning and once at the end,” says Waldron. “That is to say, a site with terrific ratings that seems to be doing everything right, may get worse results than a site that seems to be doing things wrong. Usually the two measures correspond, but not always. And we don’t know why.”

CEO Rob Waldron also created a system of regional boards in 2003. The regional boards do not have governance or fiduciary duties, but instead work to increase financial resources, help coordinate with college campuses, and increase public awareness of Jumpstart. Waldron says the organization is working to share regional-board best practices across regions, to perfect this governance structure.

Capital

Securing capital to support growth has been by far the biggest source of worry and frustration for Jumpstart. While the organization successfully raises revenue to support existing sites, finding the capital to open new sites has been more challenging. Waldron notes says that, “We’re not capitalized well enough to achieve the rate of growth this talented management team can make possible. In the nonprofit sector, winners don’t hum and losers don’t lose. No one understands the extent to which successful organizations are capital constrained.”

In 2003, Jumpstart received 30 percent of its funding from the government, 28 percent from foundations, 22 percent from corporations, 6 percent from individuals, and 14 percent from other sources (mostly in-kind goods and services). (See Figure 2.) Waldron says government grants have the most rules. Individuals are the most flexible in granting discretionary funds, while foundations and corporations are somewhere in between, often giving grants for specific sites and programs.

Jumpstart received its first AmeriCorps grant in 1996, and federal dollars have traditionally been the biggest source of revenue for the organization. But a reliance on the government as a funding source has significant tradeoffs, and managing the process takes creativity and persistence. In all, Waldron anticipates that federal Work-Study dollars, for instance, can get it only as far as 150 to 200 sites before it reaches its natural growth limit.

The political environment drives the availability of government funding, such as when AmeriCorps —and therefore Jumpstart — saw cutbacks in 2003. There are often multiple claims on government funding, so the process can become extremely competitive. “People are not open to you accessing different government funds, or getting more than your ‘share,’ so we have to proceed carefully,” says Waldron.

With federal Work-Study dollars, only 15 percent of a school’s budget can be used for Jumpstart, because otherwise the program would steal too many students away from other Work-Study options like the library or cafeteria. Work-Study rules also dictate that Jumpstart can only have 40 students participating per campus. “It’s a really inefficient way to grow,” says Waldron. “We’ve got great sites where we’re turning away 80 students who want to work with preschoolers, because we’ve reached the limit of 40 on that campus.”

AmeriCorps’ constraints are similarly complex. “They have a federal pot, 50 state pots, and a regional pot. Jumpstart receives funds from all three pots,” says Waldron. “Sometimes states even compete against each other to get the regional pot.”

Although government funding has increased, Jumpstart has had a hard time matching the growth of this source with corresponding growth in foundation revenue. “The problem is, to scale up, what you do is the same thing over and over, with better results and more efficiently, at less cost,” says Waldron. “But that is not appealing to many funders, especially foundations, who are interested in discovering something new. ‘We’re doing the same thing we did last year, more efficiently and with better results,’ is not an appealing argument. There are enormous differences in cost per participant per outcome over time, and plenty of organizations that are more and less efficient.” He wants to see a world in which nonprofits are pushed and rewarded to be more and more efficient, not just to grow and do new things.

Waldron says it’s been difficult to get foundations to pay for overhead, especially for the national organization. To get around that, Jumpstart asks for specific grants for sites or new hires, such as an assessment manager. But Waldron still feels that Jumpstart consistently under-spends in such back-office areas as technology and finance.

Corporate partnerships with Starbucks, American Eagle Outfitters, and Pearson have added diversity to the revenue mix, and further validated Jumpstart’s model. For instance, Starbucks pledged $1 million in 2001 to be used over four years to fuel growth. “Corporate philanthropy requires talent and time,” says Waldron, noting that the typical corporate relationship is more like a vendor or client, and managing that relationship takes time and money. Waldron is also quick to point out the rewards of corporate funding. “Because corporate gifts tend to be large, the benefits far outweigh the costs of cultivating corporate relationships. A case in point is Starbucks’ support when AmeriCorps was being threatened. Starbucks donated a New York Times ad to the entire AmeriCorps movement to help drive change in Congress.”

Capabilities

Jumpstart faced a classic transition from a founder-led organization to professional management in 2001, at precisely the time that the organization was growing most rapidly (29 percent annual revenue growth).

Lieberman was tiring of fundraising and “doing the same thing,” so he shared with the board his interest in leaving. The organization experimented with hiring a chief operating officer to take over operations, but there wasn’t a good fit, and Lieberman and the COO clashed.

Jumpstart tapped Spencer Stuart to search for a chief executive officer with experience growing large organizations. They found the right match in Waldron, an educational entrepreneur with expertise in scaling a local after-school program into a national organization.

Lieberman managed the transition gracefully, courting the new CEO and working for a year to manage the handoff and step aside. “The thing that’s remarkable is that Aaron genuinely stepped away and created space for Rob,” says a former board member. “And Rob very smartly engaged Aaron. For example, at the first fundraiser at Bain Capital, Rob spoke and Aaron spoke. Rob would ask Aaron to help with fundraising and other things.”

But it was a rocky time for the organization. During the leadership transition from Lieberman to Waldron, Jumpstart was perhaps three months from insolvency. Foundations were taking a wait-and-see approach to the crisis. There were also tough decisions to make once Waldron came on board. “We had too many people, and we weren’t paying enough,” remembers Waldron. He laid off 10 people in his first month and brought in new and more seasoned executive talent at higher salaries. The average salary went from $39,000 to $54,000. The organization’s payroll stayed the same, with the decrease in total headcount offsetting the increase in average salary.

Waldron also felt the organization’s overhead was too high, especially in Boston. “We cut costs per tutor-hour by 26 percent, in part because economies of scale kicked in as we were serving more and more kids out of the same home office.”

Growth benefited, rather than suffered, from these headcount and cost cuts. “Even with a smaller headcount, we were able to keep the growth going, by taking advantage of the higher level of talent we’d brought in and by cutting costs. When we lost AmeriCorps funding and revenues were flat in 2003, we still managed to increased kids served by 33 percent.”

Looking back, Waldron thinks he took too much of a corporate approach. People were asked to leave the same day they were laid off. “This had never happened before in a nonprofit,” he says. He also changed the staff’s focus to an operational metric of cost-per-tutor. He realized Jumpstart would never scale unless its cost structure was reduced.

Jumpstart began rebuilding the organization from that point on, constructing a regional team to better serve the increasing number of sites across the country. But staff turnover continued to create stress on the organization. People were expected to do more than they were capable of. Without well-defined career tracks and facing tremendous growth pressures, many staff left. With hard work, Jumpstart has managed to cut staff turnover in half, and growth has allowed for many of the staff to be promoted into more senior positions within the organization.

Key Insights

- Using metrics to manage quality. Jumpstart aggressively tracks metrics that demonstrate how the organization as a whole and the local affiliates are delivering on the mission. This has allowed it to ensure program quality without a corresponding increase in centralization and staff oversight.

- Transitioning from a founder to a management culture. Jumpstart successfully moved the organization away from its founder, and in the process made the program about an organization, and not a person. It learned that different stages of its organizational life required different skill sets. For instance, accelerating growth required a leader with skills in operations and scaling an organization. Although its initial effort at instituting a COO failed to produce the right results, Jumpstart’s board and founder quickly took action to skillfully transition to effective new leadership.

- Diversifying the funding base. The key to Jumpstart’s model has been relying on federal funding to fuel expansion. The organization has also used corporate partnerships to increase publicity and build a stronger network. But leveraging government and corporate support adds to the organizational complexity of program development and fundraising, and even creates its own barriers to growth.

- Coping with capital constraints. Jumpstart is widely regarded as a hugely successful nonprofit, yet it still operates on the edge, with significant funding-imposed constraints on growth. And the leadership transition was a potentially life-threatening stage for the organization.

- Infusing the organization with strategy. Jumpstart found that the infusion of strategy was helpful at key points in its growth, allowing it identify criteria for future growth and ways to maximize existing resources. Waldron also turns down funding and university partners that don’t match the organization’s mission.

Notes

[1] Headcount does not include licensees’ staff