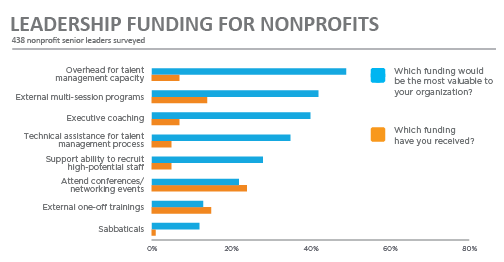

Nonprofits have a chronic leadership development problem, but funders and grantees don’t see eye-to-eye on how to solve it. Nearly two-thirds of the 50 foundations leaders who participated in a Bridgespan Group survey ranked leadership development as a top priority.1 Yet, a separate survey of 438 nonprofit leaders highlighted important differences between the support nonprofits feel they need to cultivate strong leaders and the support they actually receive.2

For example, rather than external trainings and conferences—leadership activities funders typically support (see Exhibit 1)—half of the organizations we surveyed prioritized internal talent development to help employees on the job. Few nonprofit organizations reported receiving this support, and we believe this is a major cause of nonprofits’ most pressing leadership issue: CEO succession planning.3

Exhibit 1: Leadership development funding organizations need vs. what they receive

If recognizing a problem is the first step to finding a solution, many funders appear to be open to new thinking. In our survey, fewer than one in four funders reported high confidence that they are making the right leadership investments. But their commitment to leadership funding remained high. Roughly 40 percent planned to increase their financial support in the future. As funders review and deepen their commitment to leadership, the time is right to ask how to make the most of the dollars invested. “Investing in leaders generates the highest return on philanthropic investments,” says Donna Stark, former vice president for Talent and Leadership Development at the Annie E. Casey Foundation. But it requires a thoughtful approach. “The answer isn’t just to invest more—it’s to invest more wisely,” she adds.

Maximizing investments in leadership requires understanding the challenges leaders are facing and matching funding to the approach that will most effectively solve those challenges. Based on our research and work with funders, we believe that making higher-impact leadership investments begins by making a significant investment upfront to answer two important questions: What is the problem, and what is the right investment to address that problem?

What Is the Problem?

Identifying the leadership problem in need of fixing sounds simple, but isn’t always so. The root cause for why an organization or group of organizations struggle to have the leadership they need could originate in a number of places. For instance, it could stem from recruiting the wrong people, missing talent development opportunities, or failing to create an environment that supports and retains leaders for the long term.

Our research showed that the types of support organizations prioritize differ by field (see Exhibit 2)—implying that the challenges they face may be different and indicating that there is no one-size-fits-all solution to cultivating effective nonprofit leadership. For instance, in the field of K–12 education, organizations revealed that executive coaching is the top priority, while a survey of workforce development organizations in New York City showed a significant majority prioritize overhead for talent management capacity.

Exhibit 2: Examples of Leadership Funding Priorities by Field

To understand the greatest need, we recommend that funders take a bottoms-up approach, engaging the stakeholders who understand the challenges best: nonprofit staff, boards, recruiting professionals, and other field experts. Using approaches like interviews, focus groups, and surveys, funders can get a deeper sense of what support these leaders and organizations need to cultivate talent. This isn’t to say that funders disregard grantees’ needs today. Most engage in information gathering, but all too often it isn’t comprehensive and systematic. Identifying the problems and barriers to overcoming them takes time, but it is important to get this step right in order to invest in the most useful leadership development activities.

The experience of a collaboration of over a dozen of the largest and most influential Jewish funders is a case in point. When faced with accelerating senior leader retirements across their organizations, the group sought investments they could make in the next generation of leaders for the field. Initially, the group considered a two-pronged approach: an annual high-profile networking gathering for 50 of the field’s top emerging leaders paired with an executive education program for a smaller group of leaders.

But to confirm their assumptions, the funders stepped back and conducted interviews with senior executives, emerging leaders, and search executives in the Jewish nonprofit field. They gathered input on the most critical barriers holding organizations back from having the leaders they need (see Exhibit 3 for a list of questions they asked as part of those conversations).

Exhibit 3: Interview questions to understand leadership challenges in Jewish nonprofits

This input, as well as a review of leadership programs already supporting the field, suggested a different priority. While a deeper investment in individual leaders could be helpful, staff churn would likely persist unless the nonprofits themselves became more attractive places to work and grow careers. As a result, the funders established a Leadership Pipelines Alliance (later renamed Leading Edge) with three initial initiatives: engaging the Jewish philanthropic community in stewarding effective leadership development within Jewish nonprofits, rolling out a Leading Places to Work campaign to identify best practices and provide supports to help Jewish nonprofits become more attractive places to work, and launching a CEO on-boarding program to support the new generation of leadership that was rapidly taking over the field.4

Without the extra effort involved in deeply listening to the needs of the leaders themselves, the funders may never have been able to design investments that so directly addressed the most important needs of the field. “We started the process thinking we knew what was needed and were looking for help in designing it,” says Rachel Monroe, president and CEO of the The Harry & Jeanette Weinberg Foundation and inaugural board chair of Leading Edge. “It wasn't until we asked senior and emerging leaders in the field what they needed that we realized our initial assumptions were not quite right. With this input, we now have much greater confidence that our investments have a chance to make a meaningful impact on the issues we care about. And we are continuing to gather feedback from the field as we do this work. This is an adaptive challenge which requires a constant ear to the ground.”

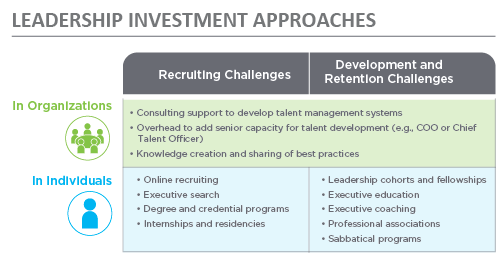

What Is the Right Set of Leadership Investments?

Identifying the problem at hand clears the way for picking the right leadership investments from a myriad of potential solutions. Bridgespan compiled a list of more than 1,000 nonprofit leadership investments and identified a number of different types of approaches funders can choose from to address the leadership challenges they uncover (see Exhibit 4). Many are the traditional tools, like executive education and fellowships. However, our research revealed a number of other ways to cultivate leaders, including several less-used but highly effective ways to provide the support nonprofits say they need most: building in-house talent management capabilities (see sidebar, “The Power of Investing in Organizations”).

Exhibit 4: Examples of approaches funders can use to address leadership pipeline challenges

A review of leadership investments reveals a wide range of cost per individual. For example, providing executive coaching can cost less than half as much as an executive education program, but coaching may be as—or more—effective, depending on individual needs. Maximizing the effectiveness of leadership investments requires answering a number of questions:

- What is the best solution or mix of solutions to meet the challenges identified?

- What is the most effective way to deliver solutions to ensure lasting impact? (e.g., what depth and duration is required per individual to have lasting influence?)

- What is the most efficient way to deliver solutions to maximize the number of individuals served?

- What operational support is needed to ensure the program delivers high quality results?

The team at The Tiger Foundation used this way of thinking about the right leadership investments when determining how best to support leadership on the issues it cares about.5 Tiger, which strives to break the cycle of poverty in New York City, observed several years ago that a number of its grantees were struggling to attract, develop, and retain their people. As a result, grantees did not have the pipeline of leaders they needed for the future.

The foundation at the time directed its leadership investments primarily into sending grantee executives to an executive education program at the Columbia Business School Programs in Social Enterprise. While the program served those individuals well and made them better contributors to their organizations, it didn’t address the systemic challenge organizations had grooming and retaining talent and planning for succession, which was impacting their organizational performance.

“High quality executive training programs like Columbia’s are great, in that they are already established, highly regarded, and relatively cost-effective,” says Charles Buice, president of the Tiger Foundation. “However [investing in individuals] does not preclude the need to make more sizable investments at the organizational level, which while more expensive at the outset, can be equally, or more, cost-effective, since institutional investments might impact 100 leaders over time and transform the organization into the kind of place that has human capital development as part of its DNA.”

Tiger researched ways to help grantees establish processes to grow leaders in-house and decided to fund grantees to work with external consultants to put effective practices in place. AchieveMission worked with six Tiger grantees in this way. “We supported these exemplary organizations to embed tailored systems that helped them identify the most promising future leaders and develop them in the most effective way,” says James Shepard, AchieveMission’s CEO. “In several cases, these nonprofits saved tens or even hundreds of thousands of dollars in recruiting fees alone even as they built stronger organizations that are better able to promote from within for critical roles.”

While Tiger continued to provide funding to individuals to attend Columbia, the added investment in grantee organizations enabled Tiger to support the development of many more leaders now and in the future.

The Power of Investing in Organizations

As the Tiger Foundation example highlights, investments in leadership don’t just have to be made at the individual level. Supporting organizations to build their ability to attract and cultivate talent can be very powerful as well. In fact, our survey revealed that funding to build internal capacity to develop staff was the No. 1 type of support organizations want, more than funding to send their leaders to external leadership trainings. Research supports the effectiveness of this approach. The 70/20/10 leadership development model, widely used among for-profit businesses, asserts that adults learn approximately 70 percent through on-the-job stretch opportunities, 20 percent through coaching and mentoring, and 10 percent through training.6 This requires that organizations have the capacity and capabilities to make those development opportunities available. Funders can help to ensure that grantees are prepared to support in-house talent development by reviewing any restrictions placed on what grantees can spend on overhead—the catchall term for administrative expenses that includes leadership development. Bridgespan research shows that most large funders cap overhead at 15 percent, while actual overhead expenditures run double or triple that amount.7 Such restrictions leave nonprofits scrambling to pay routine administrative costs, such as salaries, travel, utilities, and information technology. Faced with tight overhead budgets, leadership development easily falls by the wayside.Tiger’s experience underscores the value for funders in continually evaluating their leadership investments and evolving their approach based on what they are learning. While most funders we surveyed (86 percent) use some type of evaluation metrics to measure their success, nearly half of those rely primarily on self-assessments and anecdotal feedback. Very few conduct rigorous third-party evaluations. For example, in a 2015 survey of social sector fellowship programs conducted by ProInspire, a nonprofit leadership development organization, only 26 percent of the programs had performed an evaluation.8 Granted, leadership development is notoriously difficult to measure. But that doesn’t mean that funders should give themselves a free pass. The lack of rigorous evaluation not only prevents funders from understanding whether their investments are effective, but it also means the evidence base for what works to effectively cultivate leaders is thin across the sector.

Closing the Gap between Funders and Grantees

Investing in the development of strong and dynamic leaders is a worthy priority for any foundation. Yet, the gap our survey discovered between funders’ good intentions and grantees’ needs prevents funders from realizing their goals for building stronger nonprofit and field leaders. Closing that gap will require funders to think and act differently, whether loosening the grip on overhead expenditures, or taking more time to dig deeply into the leadership challenges of individual grantees. Leadership clearly matters when it comes to achieving impact. It’s an investment worth making.

Libbie Landles-Cobb is a Bridgespan manager and coach for Leading for Impact, Bridgespan’s two-year strategic consulting program for midsize nonprofits. Kirk Kramer is head of Bridgespan’s Leadership practice and manages Leading for Impact. Betsy Haley Doyle is a Bridgespan partner in the San Francisco office and co-lead of the Education practice.

Sources Used for This Article

1. In August 2015, The Bridgespan Group surveyed over 50 senior executives from independent, family, corporate, community, and other public foundations with budgets ranging from $500,000 to more than $100 million.

2. In January 2015, The Bridgespan Group surveyed 438 nonprofit senior leaders on their ability to recruit, develop, and retain senior managers.

3. Katie Smith Milway, Kirk Kramer, and Libbie Landles-Cobb, “The Nonprofit Leadership Development Deficit,” Stanford Social Innovation Review, October 22, 2015.

4. Susan Wolf Ditkoff and Libbie Landles-Cobb, Leadership Pipelines Initiative: Cultivating the Next Generation of Leaders for Jewish Nonprofits, The Harry & Jeanette Weinberg Foundation, March 2014, http://leadingedge.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Leadership-Pipelines-Initiative-Report-March-2014.pdf

5. Both of the case studies in this article were Bridgespan clients.

6. Ellen Van Velsor, Cynthia D. McCauley, and Marian N. Ruderman, Handbook of Leadership Development, Center for Creative Leadership, 2010. Jeri Eckhart-Queenan, Michael Etzel, and Sridhar Prasad, “Pay-What-It-Takes Philanthropy,” Stanford Social Innovation Review, June 2016.

7. Jeri Eckhart-Queenan, Michael Etzel, and Sridhar Prasad, “Pay-What-It-Takes Philanthropy,” Stanford Social Innovation Review, June 2016.

8. Monisha Kapila and Nicolas Takamine, “Social Impact Fellowships: Building Talent in the Social Sector,” ProInspire, May 2015.