Imagine a world where racial disparities in healthcare could be virtually eliminated. Actually, there is no need to imagine: it has already happened at a medical center in Greensboro, North Carolina, for Black and white patients with breast and lung cancer.

Think about that: a critical pathway to closing the racial gap in health outcomes in the United States may already exist. Prior to the work of the Greensboro Health Disparities Collaborative (GHDC), white patients were completing their cancer treatment at a significantly higher rate than Black patients, with a gap of approximately 7 percentage points. To be clear, when it comes to cancer, not completing treatment is fatal.

All it took to close the gap and improve treatment-completion rates for everyone was an unwavering focus on the root cause of the disparities: namely, the structural racism in the healthcare system itself.

Funders were increasingly interested in incorporating racial equity in their giving even before 2020, [1] when the compounding crises of the COVID-19 pandemic and the nation’s systemic racism came to a head. Since the police murder of George Floyd, even more funders expressed aspirations to be explicitly anti-racist.

But after pledging to give more to racial equity, many funders are finding they are unfamiliar with the type of work they are increasingly being called on to support. And as the national conversation around race, racism, and inequity constantly evolves, funders are left unsure of how to keep up or where to go next.

The Bridgespan Group heard this uncertainty in some of the responses to our research with Echoing Green, Racial Equity and Philanthropy: Disparities in Funding for Leaders of Color Leave Impact on the Table and the accompanying Stanford Social Innovation Review article, “Overcoming the Racial Bias in Philanthropic Funding.” Some funders were moved to act, but shared candidly and somewhat vulnerably their reservations. In short, for funders who have embraced a racial equity lens in their philanthropy, what does it really mean to give in ways that will help create an equitable society?

In our conversations with clients and others across the sector, we find that a frequent barrier to taking action is that the kind of work needed to achieve racial equity can feel slow, amorphous, hard to measure, even risky for funders. The feedback convinced us that, perhaps, these types of concerns reflect a need to develop a more accurate understanding of what it takes to address root causes in ways that will lead to lasting equitable change.

That is what our research here tries to do. Through exploring efforts like GHDC, we offer funders a look behind the curtain of what this type of work entails and some lessons to be learned. For instance, take the common characterization that work to achieve racial equity that might take decades is a “long” time horizon. What makes that timeframe “long,” and not a standard expectation? What if we reframe our thinking about equitable systemic change to consider work that does not take decades as unrealistically short? After all, given the time span that our racial inequities have persisted—lifetimes and longer, many times over, at least—then what is the more realistic time span to expect racial equity to take hold?

“Some people are creating strategies within a grant cycle as opposed to ones that actually advance a particular goal,” says Thenjiwe McHarris, co-founder of Blackbird, which helps to build grassroots efforts working toward racial justice. “We need to operate in multi-decade strategies rather than multi-year strategies. If we don’t know where we want to be decades out and we only focus on the short term, then I think in some ways we’ve limited ourselves.”

At Bridgespan, we, too, have been going on a journey as an organization to understand how we might center racial equity in our work both internally and with our clients. We are experiencing some of the same uncertainties that funders have been feeling about how exactly to live into a desire for a world characterized by equity and justice. Part of our own learning has been a commitment to consistently examine the role of race and racism in our analysis and research of problems. And that includes helping all of our US-based clients grapple with the role that structural racism plays. We have seen that when donors and organization leaders address social problems without this attention to structural racism, population-level change for all is unattainable. For instance, in our research on field-based efforts to combat complex social problems, we found that some of the sector’s biggest “success” stories, such as the decline of teen smoking or increase in hospice and palliative care, tell quite different stories when you disaggregate the results by race.

"We need to operate in multi-decade strategies. If we don’t know where we want to be decades out and we only focus on the short term, then I think in some ways we’ve limited ourselves."

For this research, we also partnered with the Racial Equity Institute (REI). Committed to the work of anti-racism transformation, REI conducts workshops to foster an understanding of the history of racism embedded in our institutions and systems with a goal of helping individuals and organizations develop tools that challenge patterns of power and grow equity. REI has been instrumental in our learning, both for this research and for our own organization. (REI has also worked with GHDC.)

"As the South goes, so goes the nation."—W.E.B. DuBois

We hope you notice that all our examples in this report are from the South. That was deliberate. One reason was a desire to shine a spotlight on work from a region of the country that traditionally gets comparatively less philanthropic attention. Despite recent growth in the number of regional and national foundations prioritizing investments in the South, the region still receives less than 3 percent of philanthropic dollars nationwide, according to Grantmakers for Southern Progress, a member-based organization of funders interested in equity-focused structural change. [2]

Another reason for our focus on the South is an attempt to reframe the narrative we often hear from funders that equity work is hard. Organizations and efforts attempting to dismantle structural racism in this part of the country, like the few we highlight in this research, understand just how hard it can be perhaps better than any, given the region’s history and current political climate.

“It is a very different lens in the South because you have a place where the primary economy was based on free labor. Because of that, there is a culture that looks at communities of color, particularly Black communities, as a commodity and not as partners or human beings. That ‘master’ framing then translates into public policy,” explains Nathaniel Smith, founder and CEO of Partnership for Southern Equity. “It makes the work a little bit more complicated.”

Yet, despite that Southern complexity, you will see that these types of efforts are still succeeding. So, yes, this work might be hard, but it’s not impossible. And that, we hope, serves as an inspiration.

What Is Structural Racism, and Why Does It Matter?

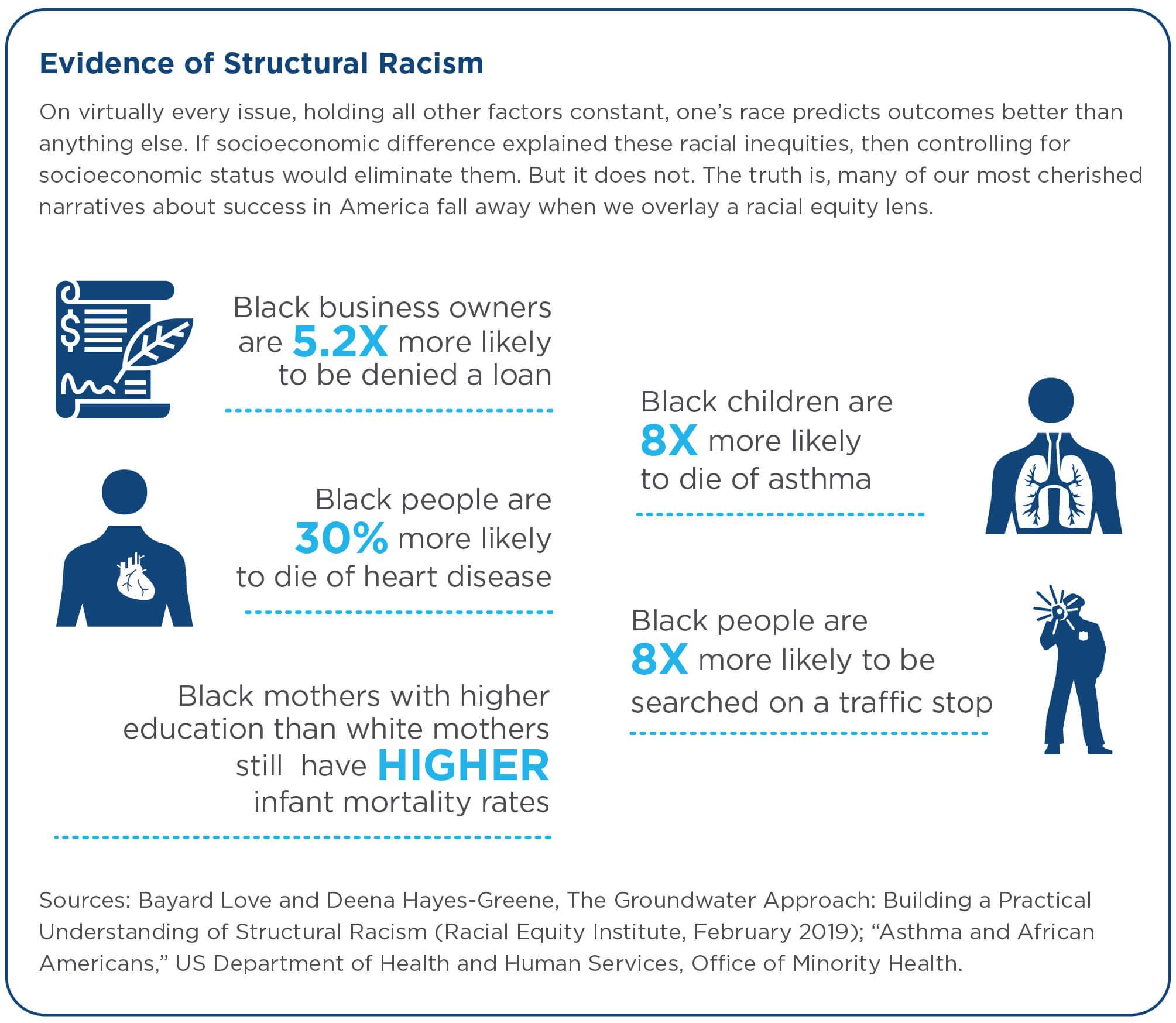

Although racism in the United States is often seen as the infliction of individual biases and hatred, racial disparities and inequities are products of something bigger than a few bad apples. Instead, societal structures can perpetuate racial and ethnic inequity.[3] Structural or systemic racism occurs when public policies, institutional practices, cultural representations and other norms work to perpetuate and often reinforce inequity.[4] Therefore, structural racism is not something chosen by a few people to practice. Rather, as the Aspen Institute Roundtable on Community Change explains, structural racism “has been a feature of the social, economic, and political systems in which we all exist.”[5]

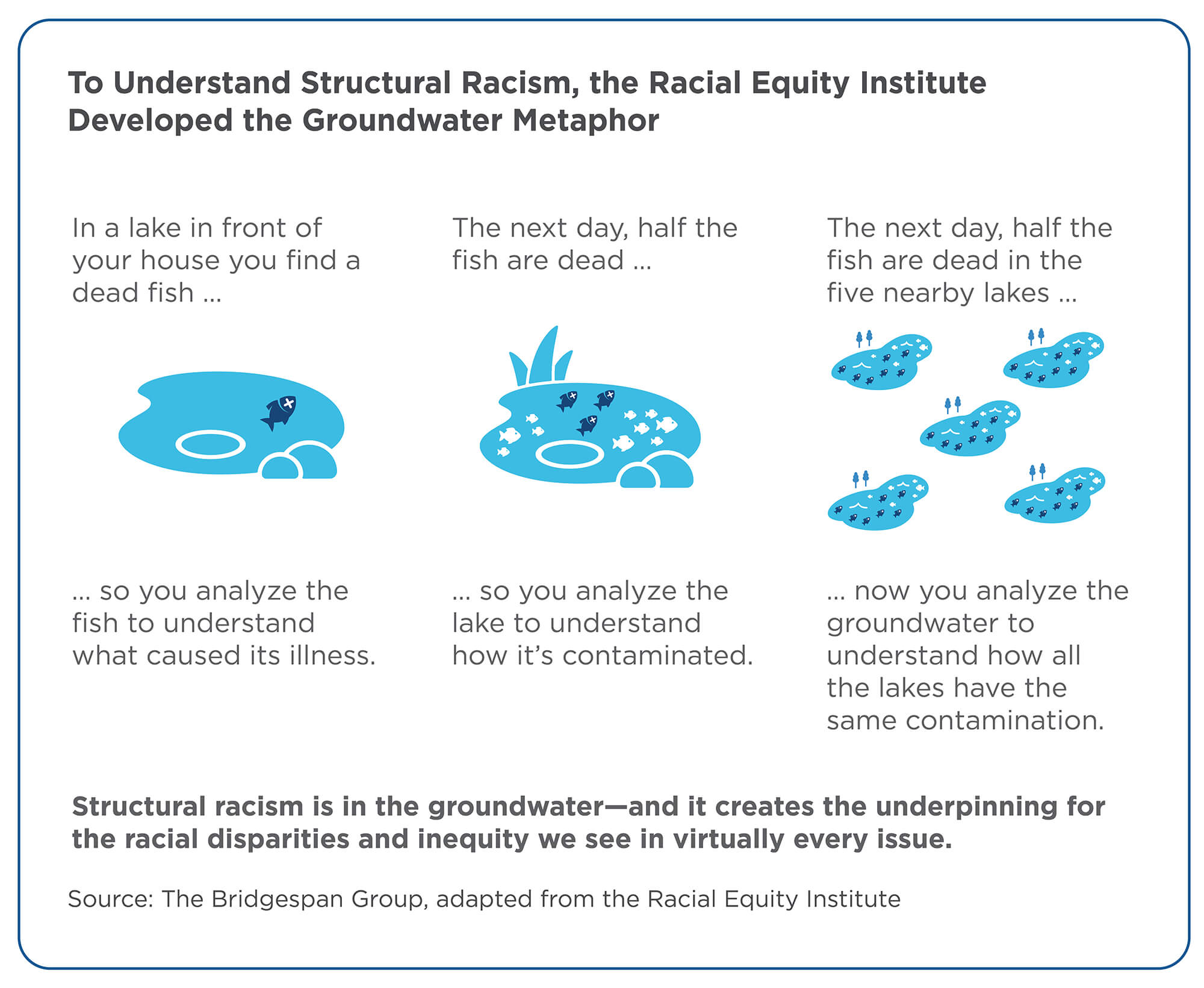

In an effort to understand how race and racism are intricately linked to our biggest social problems, REI has come up with a helpful groundwater metaphor to explain structural racism. Imagine that you have a lake in front of your house. If you find one dead fish and you want to understand what caused its illness, you might analyze the individual fish. But if you come to the same lake and half the fish are dead, then you might wonder if there is something wrong with the lake and analyze that. But what if there are five lakes around your house, and in every lake half the fish are dead? Then it might be time to consider analyzing the groundwater to find out how the water in all the lakes ended up with the same contamination.[6]

With this in mind, REI organizers like to point out that structural racism is the problem—it’s in the groundwater—and that the racial disparities and inequity we see in virtually every issue, from education to healthcare to housing and beyond, are manifestations of that problem. In addition, the National Equity Project explains, it is critical to consider that, because structural racism has become normalized, policies and practices routinely ensure access to opportunity for some and exclude others.[7]

As a result, race is one of the most reliable predictors of life outcomes across several areas, including life expectancy, academic achievement, income, wealth, physical and mental health, and maternal mortality. Furthermore, as Heather McGhee illustrates in her book The Sum of Us: What Racism Costs Everyone and How We Can Prosper Together, the structural racism that infects our society hurts not only people of color, but also white people. By documenting some of the nation’s history of discriminatory policy, she argues that, although there is no denying that such racism hits communities of color “first and worst,” the same practices that disproportionately do harm to people of color eventually engulf white communities, too.

In practical terms for funders, what all this means is that philanthropy can’t expect to achieve the lasting social change it seeks without addressing the structural racism at the root cause of our inequities.

Jeff and Tricia Raikes have been making this case in philanthropic circles for years. During our previous research with Echoing Green, Jeff Raikes shared: “Tricia and I recognize that we come into this work with blind spots, as did many of our staff. Over the past few years we have challenged ourselves to better understand the ways a race-conscious approach leads to better results for the communities we want to support.”[8]

The couple’s thinking on these issues continues to evolve, along with their approach to giving. After the conviction of Derek Chauvin for the murder of George Floyd, the Raikes opined about the prevalence of anti-Blackness, which led them to a critical conclusion that has influenced their philanthropy: “The way our systems marginalize and discriminate against Black people begins in their mothers’ womb. Studies have shown that Black boys as young as four years old are viewed by adults as ‘dangerous.’ Our society treats young Black boys like adults, ascribing malice and intent to normal childhood behaviors and paving the way for the harsh discipline and violence they endure throughout their lives. Black boys are suspended, expelled, and otherwise disciplined in school at a disproportionate rate compared to their white peers. They are tracked into less-rigorous courses during school that will make them less likely to attend college. Upon entering adulthood, having a name that ‘sounds Black’ on a job application is a fast-track to the reject pile. Black men are more likely to be victims of violence, to be homeless, and to be pushed into a criminal justice system that rarely grants them justice.

“Why? Our country’s systems were built to do this, and it will keep happening until we transform them.”[9]

What Do Interventions That Address Structural Racism Look Like?

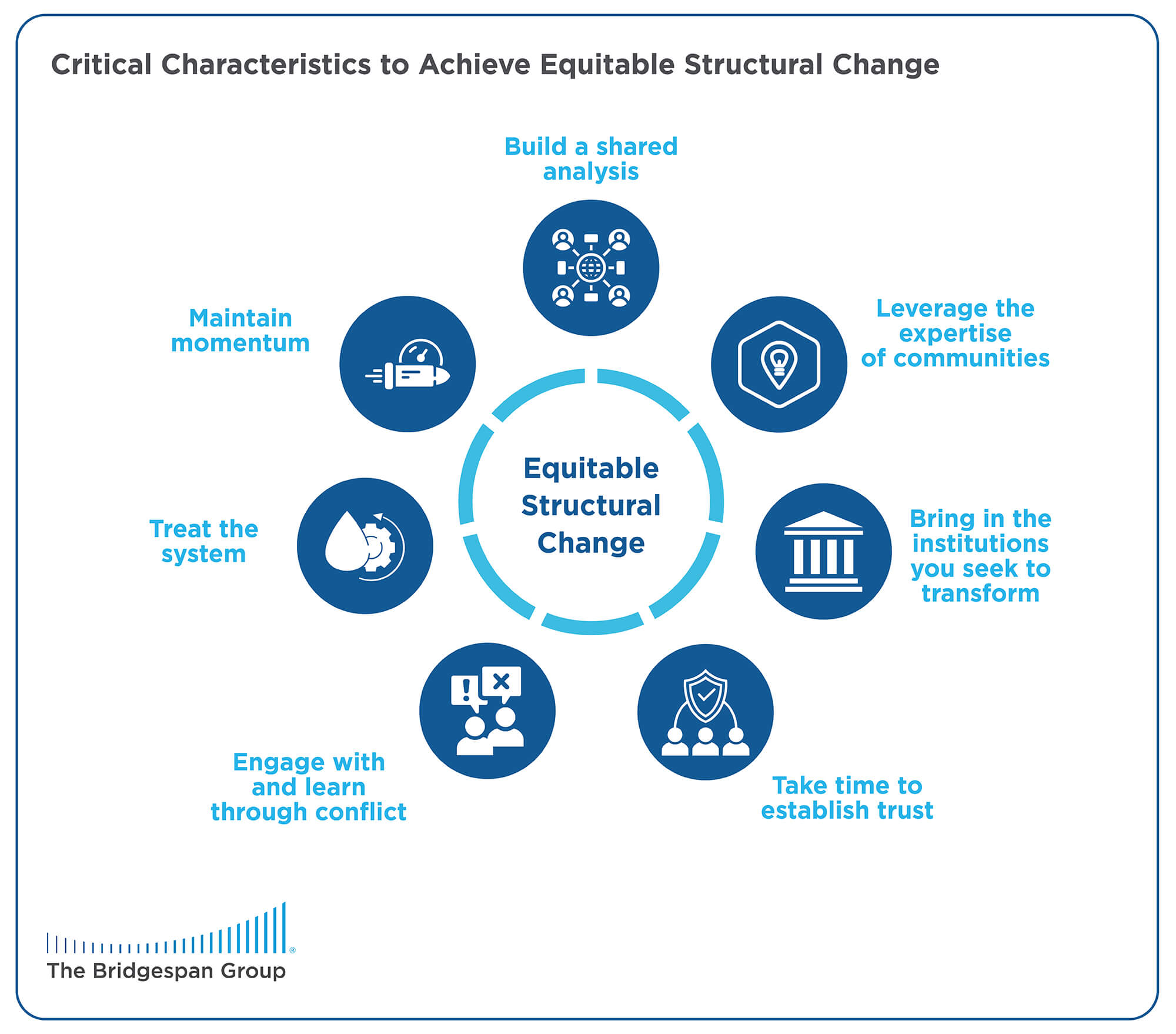

There are many efforts at various stages across the United States currently engaged in work to achieve equitable structural change. We found that such work often exhibits seven critical characteristics:

- Build a shared analysis

- Leverage the expertise of communities

- Bring in the institutions you seek to transform

- Take time to establish trust

- Engage with and learn through conflict

- Treat the system

- Maintain momentum

Depending on how the work has evolved, efforts may hold just some or all of these characteristics. Some efforts may have been in existence for decades but are still at an earlier stage of progress because of characteristics that have not taken hold yet. Although the work of the GHDC takes place at just one institution—a single lake rather than the entire groundwater, to use REI’s metaphor—we chose to focus on it because it exhibits each of these characteristics, and each was critical to the transformative change GHDC was able to achieve.

The story starts in 2003, when the National Academies’ Institute of Medicine (today known as the National Academy of Medicine) issued a report commissioned by Congress that documented significant and pervasive unequal treatment based on race in the healthcare system across the nation.[10] Looking over a 10-year period, the groundbreaking 750-page tome found that people of color receive lower-quality healthcare than their white peers even when insurance status, income, age, and severity of conditions are comparable.[11] The report concludes that such differences in treatment contribute to higher death rates for people of color. And these disparities could not be explained by the all-too-familiar narratives that blame people’s behavior, culture, economic status, or genetics. Instead, the problem, the study showed, is not with the people experiencing the symptoms, but rather with the system and structure they live in.

Inspired by the report, community organizers affiliated with The Partnership Project, including then Executive Director Nettie Coad, or “Mama” Nettie, as she was known, took up the urgent call to address health disparities in Greensboro. (Organizers like Mama Nettie “pull people together, urge them to question their ideas, and support them as they produce and carry out a plan of action.”[12]) Being a product of organizing efforts means that the community was embedded in GHDC from the very beginning. Community members approached public health researchers at the University of North Carolina to partner on the issue.

The burgeoning multiracial collaborative was born with 35 founding members, including 23 community members and 12 medical and health professionals. Mama Nettie was the undeniable soul of the group. Eighteen years later, it remains strong—even after Mama Nettie’s death in 2012—and has seen tangible success.

The seven critical characteristics all showed up in the GHDC collaborators’ success. Here is how they did it.

Build a shared analysis

GHDC was formed as an expressly anti-racist effort. An anti-racist path to social change seeks to upend the root causes of issues—the racism and unequal arrangement of power embedded in our structures, systems, and policies—while embracing transparency and accountability. While the ever-changing long-term tactics and day-to-day work of organizers can often be difficult for funders to grasp, at the heart of such organizing efforts is “building trusting relationships that are grounded in a common analysis of power and collective action for social change.”[13]

Likewise, for GHDC’s success, it is critical that members have a shared understanding of how structural racism leads institutions and systems to produce the racial inequities that the Collaborative seeks to change. It is also important that members have the language to talk about racial inequity. Therefore, all members are required to attend anti-racism workshops that offer a historical analysis of the structural and systematic nature of racism present regardless of the issue, whether that be education, health, economic, environmental, or another social issue.

“It transformed me,” said GHDC member Eugenia “Geni” Eng of the anti-racism training. Eng is a professor at the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill (UNC Chapel Hill) School of Public Health and an expert in community-based participatory research, which GHDC employs. “It really got me to understand that what I had been doing for 20 years was not going to be effective—changing individual knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors was a Band-Aid and not a solution. Instead, what I needed to focus on was systems change. All the social behavioral science theories that I’ve been trained in and [had] been teaching did not address systemic racism and therefore did not help me understand the correlation between structural barriers in the healthcare system and race-specific health outcomes. The Collaborative’s work from the beginning was focused on deconstructing the cause.”

The anti-racism training had a similar transformative effect for Black collaborative members. GHDC member Nora Jones, who later founded the Greensboro chapter of Sisters Network, a national organization for Black breast cancer survivors, admits that she was a little skeptical about spending two full days in a room with 40 strangers talking about racism. “But it really made a big change in my life,” she now says. “I realized how little I knew about racism. All these years, even though I had experienced racism, I didn’t know anything about the history of racism and its manifestations. I did not know anything about systemic racism at that time, so I was blown away by all that I learned.”

"[The anti-racism workshop] transformed me. It really got me to understand that what I had been doing for 20 years was not going to be effective ... what I needed to focus on was systems change."

Because it is critical that collaborative members have this shared understanding and analysis, no one is allowed to become an official member of GHDC without going through anti-racism training. Members also engage in ongoing learning to keep their awakened muscles concerning these issues in shape. As GHDC was forming, it lost three members—an academic and two medical professionals[14]—who refused to attend anti-racism workshops.

Leverage the expertise of communities

GHDC did not start with developing a cancer care intervention in mind. Instead, it started with the coming together of people who had a common interest in racial health disparities. There were lots of meetings to find out how GHDC could address that interest before a project focused on cancer care was even a thought.

In the beginning, members participated in a structured storytelling exercise to explore and understand their collective and individual experiences with racism in the healthcare system. Participants were asked to reflect on how they experienced, observed, or participated in racism within their own local healthcare institution. Subgroups were formed on the basis of racial or ethnic identities so people could speak freely about their racialized experiences.

The exercise revealed that almost everyone’s lives had been impacted by cancer, specifically breast cancer, either personally or through a family member or close friend. As a result, GHDC’s first work together focused on racial disparities in breast cancer care. This community-driven area of focus reflected broader trends across the nation. Although survival rates from cancer have increased, Black patients tend to still have the highest death rates and shortest survival of any racial or ethnic group in the United States for most cancers.[15] One report suggests that Black women are 40 percent more likely to die of breast cancer than white women.[16] Research suggests that differences in care are a driver of this disparity, including differences between Black and white patients in early diagnosis, guideline-concordant treatment, and access to palliative and supportive care. For breast cancer patients, Black women experienced earlier terminations of chemotherapy. Overall, Black cancer patients also report lower levels of shared decision making with their doctors. This might seem like a “system breakdown” or an anomaly of sorts—but GHDC’s structural analysis would point out that, in truth, this kind of inequity exists across society. It is indeed the expected, albeit unacceptable, outcome of society that has racial inequity “baked in.”

In 2006, GHDC was awarded a two-year grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to conduct the Cancer Care and Racial Equity Study (CCARES), which investigated the reasons for disparities between Black and white breast cancer patients. Its community-based participatory research approach ensured that community members had equal standing with academic researchers and healthcare workers. In this approach, the lived experience of community members is as valuable, and informs the work just as much, as the medical knowledge of the healthcare members or the public health lens of the academic members. Therefore, this community expertise was not only at the heart of determining what manifestation of racism would be the focus, but also shaped interventions that were developed to solve it.

Bring in the institutions you seek to transform

GHDC purposefully included a medical institution as a fellow collaborator alongside academics and community members. In Greensboro, that was the Cone Health Cancer Center. For change to take hold, it was critical that the institution saw itself as a partner with GHDC and its mission, rather than as separate from or even a target of GHDC.

However, getting institutional buy-in was difficult at first. The biggest hurdle was the lack of understanding across the institution that the root cause of the disparities was structural racism. A focus on structural racism means focusing on the systems and policies that lead racism to be baked into an institution.

Still, hearing GHDC’s focus on the structural racism of the institution left some physicians of that very institution feeling as if they were being attacked as individuals. Even those who acknowledged that racism exists more broadly, and is even systemic in nature, were unconvinced that it applied to their own medical institution because they personally felt they were treating all patients the same. That is the pernicious nature of structural racism: it doesn’t matter whether individuals are racist or not. If the system and the policies of the institution were not designed to foster racial equity, then the structure that is formed cannot help but create inequitable outcomes based on race.

“Back in 2003, people were not listening to the [entire] phrase ‘systemic racism.’ Instead, all they heard was the word ‘racism,’ and if you used the word ‘racism,’ you were accusing them of being racist,” says Sam Cykert, GHDC member and professor of medicine at UNC Chapel Hill. His medical practice was formerly at Cone Health’s Moses Cone Hospital.

“The defense to that was ‘I take care of everyone equally.’ In these 18 years, there has been an evolution of people who are more willing to listen to the word ‘racism’ and talk about it and understand that maybe ‘system-based racism’ or ‘institutional racism’ is a thing. And certainly, since George Floyd’s murder there has been more receptiveness on the part of healthcare administrators and doctors to have that conversation. But not always.”

It wasn’t until the GHDC presented data from the institution itself illustrating differing patterns of care based on race that individuals from the institution began to be convinced. Healthcare members of the Collaborative who are comfortable speaking in both the language of the medical community and that of anti-racist analysis also helped make the case to fellow physicians. Using Cone Health’s cancer registry, GHDC was able to examine five years of care and saw that there was a longer length of time between diagnosis and the beginning of treatment for Black patients than for white patients. Such delays between diagnosis and treatment not only have been found to cause patients unnecessary stress and anxiety, but also increase mortality from 1.2 percent to 3.2 percent per week of delay.[17]

Patient interviews conducted during GHDC’s follow-up research, which included patients with breast or lung cancer, uncovered other differences in care based on race. Focus groups showed that, for Black patients, there were often delays in the hospital’s communication about their care and an insensitivity to their pain—a significant issue for a disease where both the illness and the treatment can come with tremendous pain.

Structural racism can be so baked into day-to-day life that when Black patients were asked if they were treated differently due to their race, most said they were not, unaware that they indeed were receiving worse care than white patients, as the Collaborative was able to document.

“When thinking about cancer, if the patient didn’t die, then for many people it is often seen as a success. But when you dig in, you find out that patients are having drastically different experiences on their cancer journey,” says Kristin Black, an assistant professor of health education and promotion at East Carolina University, who represented GHDC in almost all of the patient focus groups that were part of its preliminary research. “At every point, white people and people of color are being treated differently. To have evidence of that is really startling, and thinking of those stories now still hits me, because no one should ever have to experience that.”

Take time to establish trust

At the start, through in-depth discussions, the GHDC collectively created norms and principles for collaboration, formalized in a document called the “Full Value Contract,” which all members are required to sign and governs every decision and interaction. Critical for a group with people from such varied backgrounds—including race, class, gender, religion, education, and position—the contract affirms “the belief that every group member has value and by virtue [of that] has a right and responsibility to give and receive open and honest feedback.”

While the exact makeup and size of the Collaborative has been fluid over the years, a constant that has remained is the strong bond all seem to share. To achieve this, GHDC intentionally dedicates time to relationship building. The beginning of GHDC’s monthly meetings always start with fellowship, where members catch up and talk to one another, not about their work together, but about life. It is hard not to notice a comfort overflows in their joyful chit-chat, similar to the kind found when close friends finish each other’s sentences.

“We built this family based on conversations,” says Terence “TC” Muhammad, a community activist in Greensboro and co-chair of GHDC. “Now it feels like the Knights of the Round Table. I am sitting with people who may be the chief oncologist, former head of internal medicine, professors at UNC Chapel Hill. But it doesn’t matter what position you have or degree you hold, because this is collaborative work, and we all come to the same table as part of [a] group of people that organized as equal partners.”

"We built this family based on conversations. … I am sitting with people who may be the chief oncologist, former head of internal medicine, professors at UNC Chapel Hill. But it doesn’t matter what position you have or degree you hold because this is collaborative work, and we all come to the same table as part of [a] group of people that organized as equal partners."

In person, this fellowship time together was always over food. The importance of the shared meal is concrete. It acknowledges that some members coming to the meeting may not have the resources for a meal, whether that be money in their wallet or time in their day. Offering food allows everyone who enters the space to be at the same starting point. As a result, sharing meals together helped build the authentic, trusting relationships that are needed for collaborative work to succeed, a strong sense of purpose, and lasting commitment. Building similar relationships might look different in communities outside of Greensboro, but the time and dedication needed to foster such trust often does not. When the GHDC had to shift to Zoom, there was no food, but monthly meetings still began with 30 minutes of unstructured fellowship time to keep relationships strong and build new ones.

Engage with and learn through conflict

Like any collaboration, especially one that values equitable participation and decision making, GHDC’s work has not been without conflict. To deal with conflict, GHDC has something they call “pinch moments”—the practice of not ignoring tensions and having a willingness to discuss and examine them as they arise.[18]

“There needs to be a recognition that conflict is part of the process of coming to an understanding together,” says GHDC member Jennifer Schaal, a retired ob-gyn physician and a member of the board of directors for the Partnership Project. “You have got to be willing to work through the conflict, and having a mechanism to do that is important. We all need to be open to learning from each other that there are different ways to approach things. If we don’t address those differences, the conflicts get worse.”

One pivotal pinch moment came when GHDC’s initial grant proposal to NIH for its first study to research healthcare disparities in Greensboro (which later became the CCARES study) received a “non-fundable score” and terse reviewers’ comments. This untactful feedback upset community members who were new to the federal research review process for funding.

In response, community members organized a series of meetings without their fellow academic partners to air their frustrations. These meetings created a lack of transparency within the Collaborative (breaking a key anti-racism principle and collaborative norm). The tensions required multiple uses of the pinch moment norm to resolve.[19] In the end, GHDC held a special meeting to allow academic members to apologize to the Collaborative for neglecting to describe in advance the typical NIH review, decision, and resubmission procedures.

"You have got to be willing to work through the conflict, and having a mechanism to do that is important. We all need to be open to learning from each other that there are different ways to approach things. If we don’t address those differences, the conflicts get worse."

Another pinch moment was when some members, in an effort to get a grant proposal in on time, bypassed GHDC’s internal committee process, which ensures equal input in decision making among community, healthcare, and academic members. The incident caused such a rift that a GHDC member left—serving as a constant reminder for the group to lean into their Full Value Contract norms.

However, GHDC’s longevity despite intermittent conflicts over the years helps illustrate how conflict is often part of transformative work and does not have to be feared by funders. Instead, the ways organizations engage with and learn through conflict can help lay the foundation for more authentic communication and collaboration. And that impact is often more lasting than any friction along the way.

Treat the system

After the GHDC documented disparate cancer care outcomes with their CCARES study, they began to work on developing an intervention.[20] To do so, GHDC partnered with both Cone Health and the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center in order to illustrate that an equity-focused intervention could be successful across geographical and healthcare settings. The ACCURE (Accountability for Cancer Care through Undoing Racism and Equity) project, as it is known, focused on patients with stage 1 and 2 breast and lung cancer and was funded by the National Cancer Institute.[21] The goal was to test whether a multipronged intervention that changed systems of care could improve the experiences of Black patients undergoing treatment.

The intervention was designed to promote the anti-racism principles of transparency and accountability at the community, organizational, and interpersonal levels.[22] Informed by patient focus groups, the intervention had many components at each level, including the introduction of health equity training at the institutions, data tracking on care quality disaggregated by patient race in real time, race-specific feedback for providers regarding treatments, and nurse navigators who worked to improve communication between the medical center and patients. The nurse navigators offered data-informed follow-up to enhance the healthcare system’s accountability to patient needs and served as patient advocates, taking action where needed. None of the specific components operated alone; in other words, healthcare institutions could not pluck a piece out and replicate it in isolation.

The ACCURE intervention got results, showing that racial disparities in healthcare could be virtually eliminated. Prior to ACCURE, white patients were completing their cancer treatments at a significantly higher rate than Black patients, with a gap of approximately 7 percentage points. Following the ACCURE intervention, the gap nearly vanished, and completion rates for Black and white patients became similar: Black patients saw a completion rate of 88.4 percent, whereas white patients completed treatment at a rate of 89.5 percent. In a system where incomplete treatments had loomed and Black patients faced the brunt of the disparities, this intervention was a watershed.

Part of GHDC’s impact has also been changing mindsets in an institution and across a community, which would not have been possible without intention and dedication to the relational work. For instance, at Cone Health, medical professionals’ realization that bad health outcomes did not have to be about individual patients being noncompliant, but rather about a system failing to ensure all patients, regardless of race, get the quality care they need, has had ripple effects across the institution beyond cancer care, members say.

Maintain momentum

Given the baked-in nature of structural racism and its inherent unequal arrangement of power, it is critical to ensure institutions remain committed and diligent to avoid reverting to business as usual. A strong relationship with a community partner can be the driver of that accountability. GHDC was able to bring about lasting change in Greensboro because of its strong relationship with Cone Health. Having a community-based partner like GHDC question the status quo, drive priorities, monitor progress, and push the institution to do better is the foundation of the work and the work’s success.

"Trying to have the system accountable to itself just does not work. ... The kind of true relationship building that [is required] doesn’t happen over weeks or months; sometimes that takes years, while always being clear on why we are together and who the purpose of this work is for."

“Trying to have the system accountable to itself just does not work,” says GHDC member Black. “Change in Greensboro was enduring because of the relationship the Collaborative established with Cone Health. That kind of true relationship building that comes first doesn’t happen over weeks or months; sometimes that takes years, while always being clear on why we are together and who the purpose of this work is for. That is how change becomes more sustainable.”

Groundwater Change Requires Patient Investment

GHDC illustrates many of the characteristics of efforts that successfully achieve structural change in a system. Ultimately, however, to get to a more equitable society, these kinds of efforts need to happen across systems. Understandably, that might seem like a much steeper ask, but it is not impossible.

Race Matters for Juvenile Justice (RMJJ) is a collaborative working to reduce disparate outcomes for children and families of color in the Charlotte-Mecklenburg community in North Carolina. A key component of RMJJ’s work is “institutional organizing” by professionals working in various city agencies, similar to the community organizing we described in Greensboro. What started as a broad desire to improve disparate outcomes for children of color led the RMJJ collaborative to work across systems, bringing together juvenile judges, officials from the social services department, the local school district, the district attorney’s office, members of the police department, and nonprofit service providers. Ultimately, this cross-system dialogue helped the collaborative set an expansive vision of a Charlotte-Mecklenburg community where the outcomes of juvenile courts cannot be predicted by race or ethnicity.

The work is still ongoing. However, the effects of the institutional organizing and the education and shared analysis it brings are noteworthy. In an age where the US criminal justice system has come under pressure across the nation for its racialized outcomes, judges in this part of North Carolina stand out for talking openly about the structural racism they see in the legal system and are part of the work to change the status quo.

Take, for instance, Lou Trosch, a white district court judge active with RMJJ who often shares the story of two juvenile co-defendants who appeared in his courtroom for a pre-trial hearing for charges of armed robbery. They received drastically different recommendations from the prosecution: one defendant was held in detention, the other allowed to return to school under house arrest. The difference in treatment prompted Judge Trosch, then at the beginning of his RMJJ anti-racism education, to wonder about the difference between the two teenage boys. “I kept asking questions, but got no differences save one: race. The young man in detention was Black and the other was white, and that says everything,” says Trosch.[23]

For funders, one lesson to take from RMJJ is the realistic time horizon needed to allow this kind of work to take hold and the need for support over the long haul. RMJJ started its work more than a decade ago; GHDC has been together for almost two decades. Trosch represents the mindset shift taking hold that RMJJ was able to seed and propagate across the ecosystem. However, although that critical shift is the groundwork for any structural change, the over-representation of youth of color in the justice system that RMJJ is working to eliminate still remains virtually unchanged.[24] There is no way to tell how long it might be before those outcomes begin to shift—and that is important for funders to understand and embrace. An unpredictable time horizon is not unique to RMJJ; it’s common for racial justice work. Meanwhile, relationship building, which consumed much of RMJJ’s first decade, is the quiet work we often see funders shy away from, even though it is a necessary part of the journey.

How Funders Can Help

"Philanthropy has no excuse not to be the most creative space in society."

It is telling that many efforts like the ones we describe above have not pursued private philanthropy more seriously, even when often financially strapped. In part, these collaboratives engaging in anti-racism work could not see themselves or their approach fitting what they imagine philanthropists support for social change. And they’re probably not too far off, at least historically. In our own work with funders, we often hear hesitation to fund such efforts. That disconnect is a shame. There is a ripe opportunity for transformative change if more work of this kind is better resourced. After all, efforts that dismantle the structural racism at the heart of our most challenging social problems are the bedrock of building an equitable society for us all. They should be recognized and valued.

That recognition has driven the giving of The Sapelo Foundation, a family foundation based in Savannah, Georgia, which often supports grantee partners that prioritize the power-building strategies of policy advocacy, civic engagement, and grassroots organizing. These strategies are the tools that catalyze, achieve, and implement just and equitable systemic change. During the summer of 2020, in response to how the COVID-19 crisis deepened existing racial inequity, the foundation created a special two-year, $800,000 grant to help launch the Georgia Systemic Change Alliance. The initiative brought together four place-based ecosystems, or networks, as the alliance calls them, to advance three critical goals for their communities:

- Recovering, rebuilding, and reimagining systems and policies post-COVID

- Advancing the movement for Black lives and broader racial justice across systems and policies

- Building the internal muscle and infrastructure of networks for the short and long term

Each of the place-based networks is at a different stage in its respective life cycle. Together, the alliance includes more than 100 social, environmental, and racial justice organizations from across Georgia, as well as leaders of faith, government, and business.

The networks are made up differently. The Albany network, known as Reimagine Albany, is a nonprofit network led by the United Way of Southwest Georgia; Brunswick’s network, the Community First Planning Commission, is a faith-based network of 18 Black churches and allies that has been convening for more than a decade and deepened its efforts in the wake of the murder of Ahmaud Arbery near Brunswick; the Savannah network, the Racial Equity and Leadership (REAL) Task Force, is a public-private partnership led by the mayor’s office; and the statewide network, the Just Georgia Coalition, is an advocacy network that includes formal partnerships with Black Voters Matter, New Georgia Project, Southern Center for Human Rights, Working Families, Malcom X Grassroots Movement, and Black Male Voter Project.[25]

Despite their differences, all four networks have one thing in common, says Otis Johnson, the chair of the network in Savannah: “Each member of the alliance faces the same problem—systemic racism.”[26]

It is that clarity on the overarching problem of systemic racism that keeps The Sapelo Foundation from not being dissuaded by the complexity of the alliance’s day-to-day work. “I am struck when funding decisions are made by what is easily measured instead of based on deeper conversations with grantee partners about ‘Is this what you imagined racial justice would look like?’” says Christine Reeves Strigaro, Sapelo’s executive director. “If it’s not a little uncomfortable and messy, if it doesn’t require agility and pivoting, or if it doesn’t need trusted relationships and long-term networks, then maybe we are only funding things that are too safe—and maybe we are not the funding partners that we could be.”

Similarly, Nicole Bagley, board president of The Sapelo Foundation, adds: “Philanthropy has no excuse not to be the most creative space in society.” She notes that, unlike the private and public sectors, philanthropy does not answer to shareholders or an electorate. Echoing the maxim popularized by civil rights pioneer John Lewis, she offers: “If not us, then who? If not now, then when?”

The Sapelo Foundation’s $800,000 investment provided general operating support for the lead organizations of each network, funds for regrants to key members of each network, and funds for overall network needs. Additionally, the four networks and The Sapelo Foundation jointly selected the Partnership for Southern Equity, a Georgia-based racial justice organization, to provide technical assistance tailored for each network, convene the lead groups on monthly learning calls, and help write reports about the plans of each network and a case study about the behind-the-scenes work of all the networks during a critical moment in history.

In the second year of the two-year grant, funds will be in the form of a matching grant to help each network access additional resources, implement the recommendations, and build sustainable budgets for the long term. The Sapelo Foundation’s commitment goes beyond dollars, as it also hopes to strengthen these efforts by helping to build relationships and networks that can last for generations.

“I like to say that The Sapelo Foundation is in the infrastructure business,” says Strigaro, “because collaboration, network muscle, opportunities to leverage resources, strategy development and execution, and organizational health are all essential ingredients for just, systemic, and generational change.”

Lessons for Funders

Below, you’ll find some ways to effectively support this kind of work. These suggestions include both changes in thinking or approach for funders to adopt, as well as ways to change funding practices. We find that both types of change are needed for this type of work to best thrive and should be done simultaneously. In addition, the starting point is providing unrestricted long-term funding. (Ideally, something like The Sapelo Foundation’s partnership with the Georgia Systemic Change Alliance would continue beyond the initial two years.)

There have been many calls from across the sector for more unrestricted long-term funding. It is a theme often returned to when it comes to supporting systems change and racial equity work. Because the problem of structural racism is complex, the solutions are, too. To realize the full potential of the kind of transformative impact that these efforts truly have, funding has to be sustained for the long-term journey. That means sticking with this work through the ebbs and flows, starts and stops, and twists and turns it might take.

Change in Thinking

Make the Investment to Understand the Depth of Structural Racism

Learning about the history of structural racism and how it manifests in different ways to create inequitable outcomes in any institution and across systems is a necessary foundation for this work. That experience can be gained through members participating together in workshops and readings. There is an opportunity to support ongoing learning about race and racism to provide continuity through departmental turnover, policy change, and political shifts.

It is critical for funders themselves to engage in this kind of learning, as well, in order to better identify and support these efforts. However, the learning is always ongoing, so giving while learning is critical. Re-grantors and intermediaries can help. In June 2020, four grassroots organizations—Highlander Research and Education Center, SONG (Southerners on New Ground), Project South, and Alternative ROOTS—launched the Southern Power Fund. Each of the four organizations gives no-strings-attached grants to small, people-of-color-led organizations often overlooked by funders.

Shift Mindsets

Translating knowledge into action requires a deliberate shift in mindset, such as when the doctors at Cone Health came to an understanding that an individual can intend to treat people equitably and still exist within an institution or system where racism is embedded. Likewise, becoming a funder who gives in ways that authentically champion racial equity requires a mindset that does not lose sight of the foundational structural racism producing our existing inequities. The Presidents’ Forum is a peer- to-peer support and learning network, managed by leadership and diversity, equity, and inclusion expert Keecha Harris, where foundation CEOs can candidly discuss issues of equity and think through difficult questions. Similarly, the Groundwater Institute also works with philanthropists.

Change in Practice

Be Clear on Your Role and Respect the Role Others Play

Part of the magic of these equity efforts: a wide range of individuals came together to offer their unique strengths without succumbing to traditional hierarchies or allowing titles to define influence. GHDC believes that “every group member has value,” and members constantly hold on to the truth that knowledge and education are not the same thing; experience is important, too. Living into that belief, GHDC’s Full Value Contract names a list of things that as a team they value for their work together. Humility made the list. As The Sapelo Foundation modeled in Georgia, it is critical for funders to also show up with that same humility and spirit of collaboration.

Value the Work to Build Community Infrastructure

Organizing that happens outside political campaigns is often overlooked by philanthropy because it takes time and can feel less tangible. The activities show up differently depending on the setting. However, the deep relationships organizing develops represent the kind of authentic community partnership that drives this work forward and makes impact possible. Community infrastructure is necessary to hold systems accountable and protect progress made. If well resourced, it has the potential to be activated again and again to propel new and different wins. That GHDC was able to survive after Mama Nettie’s passing was a testament to the strength of the relationships and partnerships her organizing efforts helped ignite.

Moving Forward

Admittedly, dismantling the structural racism that lies at the root of many of society’s most complex social problems is perhaps one of the biggest challenges we may face. As a result, it’s understandable that this kind of work will take longer than a typical grant cycle—even decades. That does not mean success can’t be measured. But it might require a rethinking of success to anchor on progress and momentum. Funder due-diligence processes that rely on a linear theory of change that expects predictable outcomes is an approach that does not fit the adaptive nature required to achieve structural change. Instead, embracing flexibility, trust, and patience is needed.

“Overnight success often takes at least a decade or more of blood, sweat, and tears,” Strigaro of The Sapelo Foundation has said. “Grantmaking is much more art than science. Yes, there is important data that plays a critical role, and I love data. But there are also essential ingredients when it comes to timing, introductions, relationships, and creativity. I keep asking ‘what if,’ and that usually leads to better questions and answers.”[27]

In that vein, what if philanthropy took structural racism head on by supporting, nurturing, and fostering groundwater solutions? It wouldn’t mean ignoring the hurt and harm of today; on the contrary, both are needed—work that addresses the harms of today, and groundwater solutions that head off the harms of tomorrow by tackling root causes and reimagining systems to foster equitable outcomes.

In other words, what if philanthropy adopted an abundance mindset to giving to racial equity instead of a scarcity one?

For instance, imagine how much more GHDC could accomplish if private philanthropy played a bigger role in its journey. It might be as straightforward as tackling racial disparities in other types of cancer care at the hospital they are already working in. Or an ACCURE 2 could stick with breast and lung cancer care and spread to other cancer centers in North Carolina. Or do both, spreading cancer care reach both in type of cancer and location.

Right now, the Collaborative regularly fields interest from other states that it doesn’t have the resources or infrastructure to pursue. But could there be a model where GHDC’s insights are shared with other community-based efforts to drive similar success in cancer centers in communities across the nation? Perhaps the ACCURE model could move beyond cancer care to other healthcare disparities and diseases. Some members have already begun to think about and work on translating GHDC’s work to maternal healthcare, for instance. What about ACCURE for diabetes or heart disease? Or applying the model to root out disparities that manifest differently for Latinx patients or patients of other racial or ethnic identities?

Or, what if the GHDC approach moved beyond healthcare entirely and tried to chip away at the structural racism in other systems, like, say, education or the criminal legal system? A cure for the structural racism in any system—imagine that. GHDC recently wrote a research paper that investigates those types of possibilities.[28]

But the truth is, GHDC is not a singular case—the nation is filled with organizations, collaboratives, networks, and grassroots efforts similarly doing work that thinks in big, innovative ways to dismantle systemic inequity. Which brings us to our last question: what if, to finally achieve racial equity, philanthropy did whatever it takes? We invite you to try.