“Charity begins at home.” The old saying rings true for many benefactors who choose to direct funds to their communities, where their donations can make a visible difference to local organizations. But where will a donor’s charitable dollars make the greatest difference? What are the community’s most critical needs? And which of its organizations address those needs most effectively?

Traditionally, many wealthy Americans dealt with these questions by donating funds to their local community foundations. The foundation staff, knowledgeable about the community’s needs and nonprofits, assumed full responsibility for grant making decisions. In return, donors enjoyed both the fruits of their beneficence and a variety of administrative and financial benefits, including an immediate tax deduction. As the only alternative to annual giving organizations such as the United Way, and private foundations, which require assets of at least $20 million to make sense economically, community foundations occupied a unique and important niche.

Recently, however, many financial institutions such as Fidelity have introduced funds that not only provide the same tax advantages as community foundations, but also allow donors to direct their contributions to the charities of their choice. While donor advised funds (DAFs) have existed for many years, they were underutilized and unappreciated until Fidelity and others began to promote them to their clients. The appeal of these new funds has been enormous, and many community foundations have responded by allowing contributors to establish their own donor-advised funds under the foundation’s umbrella.

From a financial perspective, the move to a donor-focused approach has been highly successful. Many of the foundations that made the change have realized spectacular growth in assets, greatly increasing the flow of charitable dollars into their communities. What is less clear is how donor-advised funds have affected the overall impact of those new dollars. While individual donors bring great passion and perspective to their grant making, they are also apt to be less well informed than professional grant makers about which organizations can respond most effectively to the community’s pressing needs, and their decisions are more likely to be disaggregated, unsystematic, and uncoordinated.

Given these challenges, are there ways to improve the odds that increases in charitable giving will be matched by increases in impact? The president and board of the Greater Kansas City Community Foundation were asking themselves this question, when they joined forces with The Bridgespan Group in 2001. Ultimately, the answer led to the development of a new measurement system that enables donors to assess and compare the performance of area nonprofits in fields ranging from social services to the arts. In addition, the system is proving to be a valuable tool for local nonprofit executives and board members who are using it as a platform for improving their organizations. Performance measurement, rightly understood, can benefit both grant makers and grant recipients.

The Organization

The Greater Kansas City Community Foundation (GKCCF) was founded in 1978 by a small group of community leaders. Their aim: to create a diverse, broadbased charitable foundation that would serve the needs of metropolitan Kansas City. By the time Jan Kreamer joined as president in 1986, GKCCF’s assets totaled $40 million.

Under Ms. Kreamer’s leadership, GKCCF began moving in the early 1990s from a traditional community foundation model to one in which donors would make most of the grantmaking decisions. This donor-focused approach provided donors with the simplicity and tax advantages of a public charity, along with the personal recognition, involvement, and flexibility of a private foundation. GKCCF’s mission statement, “connecting donors to the priorities they care about, increasing charitable giving and providing leadership on critical community issues,”[1] reflects this shift. Not surprisingly, the move also involved significant changes in the organization, as the staff began to focus on helping donors make their own grant decisions instead of evaluating grant requests and tracking grant performance.

By the late 1990s, the strategy was firmly in place and proving extremely successful in increasing the flow of charitable dollars into the community. In 1998, GKCCF led all U.S. community foundations in gifts received, with more than $120 million.[2] Since then, GKCCF has consistently ranked near the top among community foundations in gifts received—fifth in the nation in 2000, according to The Chronicle of Philanthropy—as well as grants paid out, coming in third that same year behind only New York and San Francisco.

By 2000, however, Ms. Kreamer and the GKCCF board were becoming concerned that they were not doing all they could to help donors maximize the actual impact of those charitable dollars. Consequently, they decided to work with The Bridgespan Group to clarify GKCCF’s goals for impact and to define an effective strategy for maximizing that impact in line with the foundation’s distinctive skills and capabilities. In addition to helping GKCCF strengthen its service offerings to donors, this work highlighted two imperatives: First, GKCCF needed to do more to engage donors on the most important issues and projects facing the community. The foundation had always been a leader in setting community priorities and supporting major community initiatives, but it had not explicitly connected donors with these initiatives. Second, and more problematic, GKCCF needed to find a way to pro-actively help donors determine which organizations were best positioned to do good work, so that donors could make better grant decisions themselves.

Key Questions

Good data support good decisions. But in the nonprofit sector, gathering good data—and especially valid comparative data—is a problem of epic proportions. In Kansas City, as elsewhere, data on relative service-delivery performance were not readily available for a broad array of area nonprofits, and even when information was provided, it was often difficult to make relevant comparisons. As a result, GKCCF and the Bridgespan team faced several important questions as they began to address the challenge of helping donors increase the impact of their philanthropy:

- What information do donors want to inform their grantmaking decisions, and what information do they need?

- Are there existing performance measurement systems that can provide this information, or does GKCCF need to create something new?

- If a new assessment tool is needed how should it be designed? Who are the key stakeholders that should be included in this process?

- How much of the nonprofit community will GKCCF have to include in order to provide value to donors? What level and kind of resources will it take to put this system together? How should the foundation go about implementing this initiative?

Defining Donor Needs

The first priority was to understand what type of information donors would value. The project team’s initial hypothesis was that donors would welcome a ratings system, which graded area nonprofits on various dimensions and allowed direct comparisons of similar organizations. A series of focus groups with donors confirmed that they were eager for performance data, and that GKCCF had the credibility and stature to serve as their information source of choice. But the groups also made it clear that they wanted to evaluate the nonprofits’ performance themselves rather than have the foundation making assessments on their behalf. What made this problematic was the fact that most of the donors were unaware of how challenging evaluating a program’s success can be, and believed that financial measures were sufficient to inform their grantmaking decisions. So to achieve its goal of helping local donors increase the impact of their charitable dollars, GKCCF would not only have to provide objective performance data but also find ways to educate donors about the subtleties of nonprofit performance measurement.

Exploring Available Options

The team’s next step was to determine whether there was an existing performance measurement system that could satisfy donors’ needs and meet GKCCF’s donoreducation goals. The team researched both national, web-based ratings systems such as Wall Watchers, Guidestar and the BBB Wise Giving Alliance and local initiatives designed to assess the performance of Kansas City nonprofit organizations. After conducting extensive interviews with a select number of providers to gain a better understanding of their particular tool’s goals, the thinking behind the measures its designers had chosen, and the cost to create the assessments, the team reached the conclusion that none of the existing systems met GKCCF’s needs. Although the national assessment tools were donorfocused, covered a broad array of nonprofit organizations and were relatively cost effective, they were overly reliant on financial measures—relevant data but inadequate indicators of nonprofit organizations’ social impact. Conversely, the local initiatives offered in-depth assessments of program effectiveness but focused on small numbers of organizations in specific segments of the nonprofit sector such as community development or youth programs. They were also much more costly to develop and implement than GKCCF could justify. To strike the right balance among validity, practicality and cost, GKCCF would have to create something new.

Designing the New Measurement System

With donors’ wants and needs firmly in mind, the team began designing the new measurement system. The process included intensive input and feedback from a task force of greater Kansas City nonprofit leaders as well as extensive testing of the prototype with donors and local organizations.

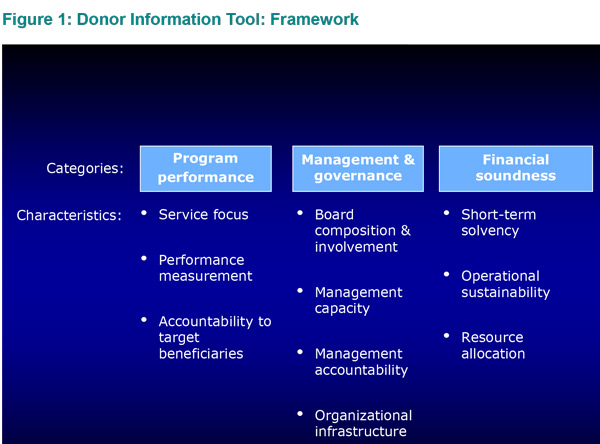

The task force members represented a broad array of community stakeholders from every major nonprofit segment, including arts, youth development, community development, social services, and education. The group’s feedback greatly informed the core architecture of the measurement system as well as the performance metrics ultimately chosen for the prototype. As “Figure 1: Donor Information Tool: Framework” illustrates, the system gathers information in three main categories: program performance, which focuses on the organization’s programs and outcomes; management and governance, which looks at its capacity to continue to deliver service; and financial soundness, which evaluates both its short-term and long-term financial health. Each category includes several characteristics that can be assessed through one or more indicators. Short-term solvency, for example, is measured simply by looking at an organization’s quick ratio, or assets divided by liabilities. In contrast, evaluating a nonprofit’s service performance requires a variety of metrics including: its mission statement and impact objective, or the results for which the organization will hold itself accountable; its ability to specify its target beneficiaries; and the actual content of its program and service activities.

To make it as easy as possible for organizations to participate and contribute their information, the measurement system incorporated data that many if not most nonprofits were already gathering and reporting. For example, the performance measurement section was modeled on the approach developed by the United Way and used the same terminology. Similarly, all the financial data were taken from the 990 form, which every nonprofit with an annual budgets exceeding $5,000 is required to file with the IRS.

The nonprofit leaders’ input also helped the team to develop a “guidebook” to accompany the measurement system. The book was designed to help users navigate the information and provided definitions of the various metrics, along with an explanation of why each measure was important and what donors should be looking for as they studied the results for an individual organization.

Once these pieces were in place, the team tested the prototype with individual donors and with 10 local organizations, chosen to reflect the full spectrum of Kansas City nonprofits. Was the end product user-friendly for potential donors? Did they find the information useful for guiding their grant decisions? Could nonprofit organizations of various sizes, engaged in a variety of activities, and at various stages of the life cycle provide the required information in a timely fashion? Were the metrics universally applicable to all types of nonprofits? Did the nonprofits’ executives think that the system could have value for them as well as for donors?

On all these dimensions, the test gave the team confidence to move ahead. The measurement tool was both cost-effective and useful for donors, providing valid information across a broad array of nonprofits. At the same time, nonprofits participating in the test reported that the information was relatively easy to collect and report. Not only that, many of them were actively enthusiastic about the tool’s potential to provide a road map for continuous improvement. Rather than resist performance measurement, as the team had feared they might, these nonprofit leaders embraced it.

Positioning

GKCCF decided to position the final measurement system to donors as an information tool to be used solely at their discretion. Communications with donors emphasized the presentation of valid, objective data that would allow them to assess the risks associated with a particular direct service organization and to make their own judgments. The positioning to the nonprofit community was equally straightforward. GKCCF presented the system as a vehicle for organizational advancement on two fronts: as a self-assessment tool to drive internal improvements, and as an efficient and effective forum in which to make potential donors aware of their accomplishments.

Implementation Planning

The 12 counties that make up greater Kansas City are home to more than 10,000 registered nonprofits, spanning multiple service areas, life stages and sizes. How many organizations would the new performance measurement system have to cover to provide value to donors? And how could GKCCF approach the segmentation and prioritization of this enormous universe most thoughtfully?

To identify a manageable universe of candidates for assessment, the team applied three successive filters: size, location and program area. First, they excluded organizations with annual budgets under $25,000, that is, those without any fulltime paid staff, which reduced the total dramatically, to about 1,900 nonprofits. Next, the team focused on the five core counties of greater Kansas City, which subtracted another 500 organizations. Finally, the team excluded organizations that fell outside the foundation’s leadership initiatives and priority areas, which were focused on the community’s greatest challenges and opportunities. What remained were roughly 500 organizations, which GKCCF planned to assess over a three-year period. Selection of the first 100 was driven by donor interest, as reflected in recent grant data, and by how instrumental the organization was to the community’s leadership initiatives. Because assessments would need to be updated annually, the budget included resources for updates, as well as new assessments, after the first year.

In March of 2002, GKCCF’s board approved a budget of roughly $270,000 for the first year of the assessment project and committed to completing 100 assessments by the end of the year. GKCCF planned to phase in annual assessments of all 500 organizations by the end of 2004. As organizations come and go, the actual number of assessments in the database at any time will vary; but the expectation is that GKCCF donors will have access on a continuing basis to detailed information on virtually any organization they might be considering.

Key Success Factors

GKCCF’s assessment tool promises to provide significant value to donors, the primary target audience, as well as to the nonprofit community, foundation staff, and individual direct service organizations. The successful design and implementation of the system depended on several key factors:

- Engagement with a broad array of community stakeholders. The team engaged GKCCF donors, staff and board members, as well as nonprofit leaders and direct service providers throughout this process. These interactions created an understanding of the value that the various stakeholders were seeking and surfaced their concerns about the project. Their input not only informed the final product, but also facilitated its acceptance.

- Multiple iterations of the prototype based on input from various stakeholders. The broad consultation process was no exercise in head nodding. The team incorporated input from multiple constituencies and then sought further input during revisions of the product. This led to a high degree of buy in among all the participants, which gave the final product strong credibility.

- A final product that built wherever possible on information that nonprofit organizations were already gathering. One of GKCCF’s key principles was not to burden the nonprofit community with yet “another funder request.” The pains the foundation took to incorporate the United Way’s models and other local models helped its relations with the areas’ nonprofits.

- Substantial investment in implementation. The GKCCF-Bridgespan team continued working together to complete the entire assessment process for half-a-dozen organizations. Every step of the process was well documented, from the initial contact with the nonprofit, through the data request, data collection, analysis, and follow-up.

- Significant commitment of resources from GKCCF. The leadership of GKCCF deployed dedicated resources for this project and assigned clear accountability among senior management. Knowing that the budget was available to fully implement the program over three years gave the effort strong legitimacy.

- A high degree of transparency between the foundation and the nonprofit community. From the very beginning, when GKCCF convened a group of nonprofit leaders, and throughout the entire process, the foundation was very clear about the purpose of the project. It was very important to explain what the goals were and, explicitly, what they were not, in order to head off any potential concerns that could stem from misinformation.

Results

Through the leadership initiatives, GKCCF has been able to articulate its priorities and philosophy in a way that has clearly resonated with donors, particularly private family foundations with funds at GKCCF. The clarity of GKCCF’s vision for the future has helped these donors focus resources on critical community needs that align with their own missions; while the assessments help them highlight the organizations that are best positioned to translate their charitable dollars into community impact.

Nonprofit response to the assessment tool has generally been positive, and several organizations have realized its potential as a road map for continuous improvement. These organizations are using the tool to train board members, as well as to assist with their strategic planning process. It has also helped them provide interested third parties with important information about what they are working on and how they are trying to create social impact.

In addition, the assessment tool allowed GKCCF to identify general weaknesses across nonprofit organizations active in areas of high community need. Many of these shortcomings relate to organizational capacity, including fundraising ability and information systems. Now, having systematically identified these areas of general need, GKCCF is addressing them by developing a nonprofit capacity building fund. This fund will be targeted at nonprofits operating in areas identified as community priorities, which are delivering high-quality service outcomes and have significant organizational needs.

By the end of 2002, GKCCF had completed over 190 assessments. In response to donor demand and in recognition of the need to quickly populate the database with information on organizations that map to GKCCF’s leadership initiatives, the foundation increased its assessment target for the first year of the project from 100 to 200. To supplement the efforts of the central organization in Kansas City, GKCCF has begun to roll out the assessment tool to several of its affiliated trusts in outlying counties in Kansas and Missouri. This initiative will accelerate the population of the database, which will include some 500 nonprofits by the end of 2003. GKCCF has also created a donor profile process to facilitate donor-staff relationships and to help donors identify areas of particular interest.

GKCCF is putting plans in place to analyze the overall impact of this effort on the community. Going forward, GKCCF will be using four key metrics to gauge the impact of this tool:

- Number of nonprofits that have been assessed;

- Percentage of GKCCF donor advised funds that actively participate in leadership projects;

- Percentage of fund grants that can be mapped to general leadership areas;

- Percentage of funds that use the assessment tool and process.

GKCCF is also developing a measure that will allow it to track the effects over time of technical assistance provided through the new nonprofit capacity building fund.

GKCCF’s renewed commitment to impact, manifest in its focus on leadership initiatives and the development of the nonprofit assessment tool, is having a profound effect on the Kansas City area. Through these initiatives, GKCCF aims to increase dramatically the flow of human and financial capital to key community priorities and high performing nonprofits. Together, they are supporting GKCCF’s efforts with both donors and nonprofits.

Sources Used for This Article

[1] GKCCF website

[2] Columbus Foundation survey, October 1999