California public schools are a melting pot. More than 50 languages are spoken in them. Over 45 percent of their students are Hispanic, nearly 10 percent are African American, and 15 percent are from other minority groups.[1] And this melting pot is growing. California public schools educated nearly 6.3-million students in the 2003-04 school year, over 1 million more than they did just a decade earlier.

As the California school system expands in response, it is failing to meet students’ educational needs. Less than half of the state’s fourth graders have basic reading skills and only two-thirds have basic math skills.[2] Only 71 percent of its high-school students graduate with a diploma, a number that falls to 57 percent for African Americans and 60 percent for Hispanics.[3] Many schools are woefully overcrowded, and low per-pupil funding levels have brought the system to a virtual breaking point.

Despite these bleak statistics, Don Shalvey (former superintendent of the San Carlos, CA school district) believes strongly that every kid in California deserves a great education. This belief led him in 1993 to found the first charter school (an independently-run public school) in California. Compared to standard public schools, charters allow school leaders greater autonomy in running their schools in return for a higher level of accountability for student success.

Shalvey’s first charter school attracted a great deal of attention, and soon he was working with Reed Hastings, a Silicon Valley high-tech entrepreneur and former teacher, to change the state’s charter laws. Their goal: to make way for more charter schools. From those early efforts, Aspire Public Schools was born. The organization launched its first two schools in the fall of 1999 in California’s Central Valley. After just four years in operation, University Charter School in Modesto and University Public School in Stockton each demonstrated excellent results with their students, receiving a nine and an eight (out of 10) respectively on the state Academic Performance Index (API) tests.[4]

The flexibility of the charter-school environment allowed Aspire to introduce several key structural changes: small, multi-grade classes; teachers who stayed with the same cohort of students for multiple years; extended school days and years; and Saturday school. Aspire also drew from the latest research to create a college preparatory curriculum that emphasized inter-disciplinary projects, individualized learning plans, and longer classes to give students more time to engage in each subject.

Building on the strong performance of its two schools in the suburbs of Modesto and Stockton, Aspire branched out into even tougher urban environments. Shalvey and his team opened schools in Oakland and East Palo Alto—places where 70 percent or more of the kids qualify for free or reduced-price lunch—also to remarkable results.[5] By Aspire’s fifth anniversary, it was operating 10 schools in the Central Valley and Bay Area and was recognized as the leading charter management organization (CMO) in the state.[6]

Impressive as these early results were, Shalvey and his Aspire colleagues were unsatisfied; success wasn’t just about opening one, or 10, or even 100 great schools. It was about transforming education for all kids in California. With this goal in mind they secured $4.7M in grants from The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the New Schools Venture Fund to expand Aspire’s efforts and engaged with the Bridgespan Group in September of 2003 to chart a course for maximizing impact.

Key Questions

Over a period of five months, a project team consisting of Shalvey, Chief Operating Officer Gloria Lee, Chief Academic Officer Elise Darwish, and six Bridgespan consultants collaborated to answer the following questions:

- What strategy will allow Aspire to get from 10 schools to its ultimate vision of transforming education in California?

- What changes in the organization will be necessary to implement the strategy?

- How can Aspire make its work financially sustainable?[7]

Setting the Strategy

Aspire was at a critical turning point. To open its first 10 schools, the management team and board had spent most of their energy navigating the “uncharted” charter school landscape. As they looked ahead to their broader vision for statewide change, they realized there were numerous potential pathways they could pursue to try to get there. To select the best one, they needed to step back and clarify the organization’s overarching theory of change—the cause and effect logic that would explain how Aspire would convert its organizational and financial resources into the desired social results.

Defining the Organization’s Theory of Change

As Aspire’s leadership began to discuss and debate the theory of change, they quickly realized that they would need to do much more than open additional Aspire charters if they were going to transform education in California. No matter how successful Aspire’s schools were, they might very well be regarded as a fluke if other CMOs were not able to accomplish the same thing elsewhere in California. Aspire needed to continue and strengthen its efforts to build the CMO field by codifying and sharing its lessons and strong practices.

They also knew that capacity-building efforts wouldn’t be enough to give rise to a thriving California CMO network. Even the most effective efforts to share knowledge with other CMOs wouldn’t take hold if the California education environment were hostile to charter schools. Aspire’s leadership would need to keep advocating strongly for new policies, practices, and institutional changes at the state level: adjusting the funding structure to give schools more freedom; changing school regulations to allow for more flexible schedules, and changing state and district regulations governing transportation, special education, and other services that may need to be delivered in new ways to better serve students. To advocate effectively, they would need to forge relationships with key decision makers in the state legislature, Department of Education, and Governor’s office.

Beyond capacity building and advocacy, a major wrinkle remained: it was highly unlikely that charter schools alone would ever be the answer. While charters were an important example of a new approach to education, there would never be enough of them to reach all the students in need. Rather, charters would be the lever for change that pushed districts to adopt new practices and break out of old, unproductive cycles.

Among Aspire’s leadership, there were two competing theories for how this change would occur. Some members of the team wanted to concentrate Aspire schools in a single district. This approach (dubbed the “competitive approach”) relied on market-based competitive pressure to drive change. As Aspire schools drew students away from the existing public schools, the financial pressure from the accompanying loss of per-pupil revenue would, they reasoned, force the district to adopt new practices to retain students.

Others on the team believed that the organization should spread schools across a broad geographic area, to show that the model worked in a variety of environments. This approach (named the “cooperative approach”) hinged on using the successes of Aspire schools to encourage districts to adopt similar practices and establishing statewide policies that required them to do so.

Charters simply had not been around long enough to allow Aspire’s leadership to decide definitively between the competitive and cooperative approaches. But they did know that if they took too many students from a given district, it was likely to fight back. Districts historically had responded to large-scale encroachment by making critical services for charter schools very expensive or threatening to revoke the schools’ charters. If the charters withstood these threats, over time they could push the district to change—but that would be a long and difficult road to travel. And they would end up spending precious resources fighting the district instead of educating kids. This clearly argued for the cooperative approach.

One question nagged at them, though. What if cooperation wasn’t forceful enough to move the needle of district reform? To address this concern, the team decided on a strategy that would focus its efforts on the cooperative approach, but leave the competitive option open if it became necessary to use it. They would identify a small number of cities or districts with which they could build cooperative relationships, thereby establishing a critical mass of schools that would serve as a “learning lab” for the districts and build momentum for reform. If, however, districts rebuffed Aspire’s cooperative efforts, the organization would shift to the competitive approach. (See Exhibit A for a schematic of Aspire’s three-pronged theory of change.)

Finding the Right Scale for Change

The theory of change articulated the levers the organization needed to pull. The next piece of the puzzle was how big Aspire’s network needed to be. Aspire already had 10 schools up and running, but how many did it ultimately need to catalyze statewide change?

To tackle this question, Shalvey reflected on his early experience working with Reed Hastings to change the charter laws. Navigating the political waters took a level of clout and credibility that Shalvey (from his experience as a founder of California’s first charter school and superintendent) and Hastings (from his business ventures) were able to provide. Aspire needed a “seat at the table” in the reform dialogue and Shalvey believed that would require working with enough disadvantaged kids to make policy makers take notice.

Exhibit A: Aspire’s Theory of Change

To put some boundaries around what “enough” might look like, the project team ranked Aspire’s network size against California districts in which at least 70 percent of students received free and reduced-price lunch (F/RL)—an indication of economic disadvantage. At 50 schools, Aspire’s network would be comparable in size to the top five districts in terms of number of schools and to the top 10 for number of students (see Exhibit B). All agreed that these numbers felt significant enough to get them that seat at the table.

Exhibit B: Aspire’s rank among districts serving over 70 percent F/RL students[8]

| Number of Aspire schools | Number of Aspire students | Rank in terms of number of schools | Rank in terms of number of students |

|---|---|---|---|

|

20 |

8,000 |

12 |

21 |

|

40 |

16,000 |

5 |

11 |

|

60 |

24,000 |

3 |

7 |

|

80 |

32,000 |

3 |

6 |

|

100 |

40,000 |

2 |

4 |

While 50 schools is a lot for any single organization to manage, in the grand scheme of California’s 9,200+ schools it’s still a drop in the bucket. This put a premium on Aspire placing its bets wisely. The project team spent considerable time screening for locations where Aspire schools could drive the greatest level of change. One of the toughest decisions they faced was whether to enter the behemoth of all districts: Los Angeles.

LA made an interesting candidate given how well it lined up with Aspire’s target beneficiaries. The organization wanted to work in geographies with a clearly demonstrated need—where 70 percent or more of the students are on F/RL, a high percentage of schools are scoring three or lower on the California “similar schools” Academic Performance Index (API) ranking, and the schools are overcrowded.[9] The Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD) was one of the neediest districts in the state on these dimensions, with over 75 percent of its students on F/RL, almost 30 percent in schools with low API scores, and more than 1,000 critically overcrowded schools.[10]

Reality Checking the Answer

Despite the compelling case to go to Los Angeles, Aspire’s board encouraged caution. Given both its political complexity and its distance from Aspire’s Oakland headquarters, LA was a risky proposition. The team needed to examine the LA decision more closely.

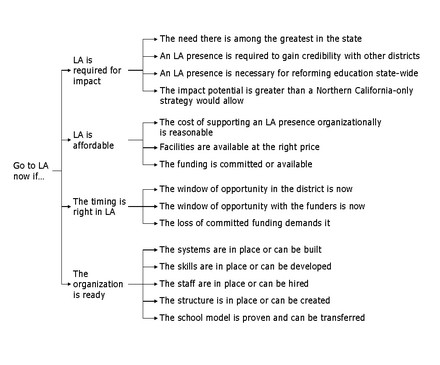

The team laid out a clear logic for “what you would have to believe” for the LA expansion to be a wise strategic choice (see exhibit C). In short, going to LA made sense only if (1) LA was required for impact; (2) moving there was “affordable”; (3) the timing was right for entry; and (4) Aspire was ready to undertake this initiative.

Exhibit C: Decision Tree for Going to Los Angeles

To determine if the move to LA was required for impact, the team considered whether there were any alternative, and less risky, paths to achieving Aspire’s ultimate goal of transforming education in California. The most obvious option for a lower-risk path would be to focus all of Aspire’s efforts in Oakland, Sacramento, and Stockton—the areas where the organization already had schools, relationships, and relatively easy access to the home office. With this approach, however, hitting the 50-school target they’d set would be next to impossible. Reaching even half that target over the next five years would require opening six to eight new schools in each of these areas. Shalvey feared that this would strain their existing relationships to the breaking point and put their existing charters (and more importantly the students they served there) at risk.

LA also appeared to be required for advocacy-related impact. Shalvey’s experience as a superintendent told him that Aspire would not be able to change policy in California without LA. One of the toughest environments, it was the acid test of whether a model could work. Additionally, approximately one third of the state government’s representatives are from LA leading the team to feel that Aspire could not get enough political leverage for its advocacy strategy without being there.

The team then turned to the affordability and timing considerations, which proved to be intertwined. Aspire needed to secure philanthropic support to fund development of the new schools and support systems necessary for the expansion. The organization already had secured $5.4 million of the $8.1 million they needed to go to LA. That left a fundraising gap of $2.7 million over the next five years. Given the commitment of many funders to the LA region, COO Lee considered that to be an attainable fundraising goal. The $5.4 million in committed funding also made the timing right to go to LA. If they decided not to go, that money would be in jeopardy as several funders had earmarked funds specifically for this expansion.

The final consideration: was Aspire ready organizationally to take on LA? Here the answer was less clear. The team assessed Aspire’s capabilities along several critical dimensions. They found that while some of the necessary elements were in place, others still needed to be developed, including: better technology, a more formal human-resource function, and knowledge-sharing systems to facilitate learning across the network. The move to LA also involved opening a significant number of high schools, and Aspire had not proven the efficacy of its high-school model yet. Furthermore, the current staff did not have all the skills necessary to support expansion, and additional staff would have to be hired to support the move.

These factors definitely were a cause for caution, but all of them were issues that Aspire’s leadership felt confident they could address. Thus, Shalvey and Lee put in place a plan to improve Aspire’s systems, hire key staff, and prepare the organization for expansion, while Darwish worked with the newly-hired Director of Secondary Education to refine the high-school model. While these investments would delay the move to LA for a year, the organization would emerge with a more solid foundation for growth, thereby mitigating some of the risk inherent in going to LA.

The decision was made. By expanding to Los Angeles and increasing its existing presence in Oakland, Sacramento, and Stockton, Aspire could establish a strong platform for creating the broader changes necessary to transform California education writ large.

Reality Checking the Answer

With the strategy and growth objectives in place, the project team turned to building the organization required to turn vision into reality. To date, Aspire had relied on a small number of key staff who made decisions collectively with little formal structure. Moving from 10 schools to 50 would require a different organization with more staff and more systems.

Determining the Staffing Required to Deliver the Strategy

To determine Aspire’s staffing requirements, the project team went back to the theory of change to establish what, fundamentally, the organization needed to be good at doing, and, therefore, the skill sets it needed onboard. They identified core processes associated with planning and opening schools, running schools, learning, and advocating.

The team mapped activities and skill requirements to each core process, and then highlighted gaps in the current organization. This is perhaps best illustrated by an example. The advocacy process involved building relationships with key state and local influencers and decision makers. It also required managing public relations and media outreach, and making targeted efforts to influence policy outcomes. The skills required for these activities included relationship building and management, political organizing, negotiating, media messaging and placement, as well as knowledge of the key players, political dynamics, and relationships required to move Aspire’s agenda forward.

At the state level, Aspire’s leadership felt strongly that this process needed to be owned by the board and senior-management team, with assistance from a public-relations consultant as necessary. This skill set already resided strongly in Aspire’s current team. At the local level, however, Aspire needed people plugged into local dynamics. The senior-management team had traditionally played this role, but this approach was becoming increasingly untenable as Aspire expanded. Aspire needed a regional vice president and potentially regional advisory boards that would represent Aspire’s interest in local advocacy issues. (See exhibit D for the advocacy staffing example.)

Exhibit D: Advocacy staffing example

Once the project team members had gone through a similar exercise for each of the core processes, they looked at the resulting positions and job descriptions. The team then re-balanced responsibilities as necessary to ensure that each of the processes was covered but that no single position took a disproportionate share of the burden.

Determining Who Works Where

Armed with the core processes and staffing requirements, the project team then turned to the question of where each position and function should reside. Historically, Aspire had served its schools directly out of its Oakland headquarters. But as the organization expanded geographically, the drive from headquarters to the schools would become increasingly long. Would they need to open regional offices to provide schools with the necessary level of support? With the decision to go to LA the following year, they needed to move quickly to establish a workable structure.

The large number of positions that required school visits pointed to regional offices. Instructional coaches, college counselors, and even technology associates needed to be on-site on a regular basis. While heretofore these positions had been in the home office (with the school support staff traveling to each school as needed), the travel was beginning to take a human and financial toll.

Adding further support for the idea of opening regional offices, there were important advocacy, community-building, and relationship-building activities that needed to occur locally. As Aspire sought to open new schools and move its advocacy agenda forward, it needed a senior presence in each of its geographies who could forge relationships with superintendents, support the principals in their efforts to build community, and navigate the local media and political environment on Aspire’s behalf. When Aspire had served just a few geographies, this work largely could be done by Shalvey, Lee, and Darwish. It now would need a dedicated senior person in each region.

Aspire would open regional offices in each of its major metropolitan areas: Sacramento, Modesto, Oakland (which would be located within the home office), and Los Angeles. Balancing quality with decentralized control, the home office would set the strategy, design core systems and processes, and manage critical functions (e.g., quality control). The regional offices, in turn, would provide local support, flexibility, and a local voice for Aspire.

Planning for Financial Sustainability

Aspire’s leadership had one final set of tough decisions to make—how to adjust their ideal model to fit the financial constraints of the environment within which Aspire operated. California has one of the lowest K-12 education funding levels in the country. It also has a relatively high cost of living. This combination of constrained revenue and high costs makes it difficult to run a school with anything but the bare minimum of staff, supplies, and support.

Aspire’s most potent weapons for fighting the financial battle were: (1) increasing the school and/or class size and (2) decreasing the level of staff support provided to the schools. The size considerations represented a direct trade-off between the quality of Aspire’s educational outcomes and the economic viability of its model. Each student brought in $6,055 in state per-pupil funding. Larger schools were more economical, as they allowed Aspire to spread the school’s fixed costs (e.g., utilities, school administrative staff) across a larger revenue base. Similarly, the more students per teacher, the more revenue per teacher, making larger classes more economical.

But large classes and large schools had non-economic costs. In large classes, teachers had a harder time giving students the individualized attention they needed. And large schools made it difficult for students and faculty to develop personal relationships beyond the classroom. Shalvey and Darwish both believed strongly that students did better in environments where they were known by most of the adults in the school, and that teachers performed better and enjoyed their work more if they were in an environment of knowing and collaborating with their peers.

To figure out the right balance between economic and educational considerations, the team analyzed the savings that Aspire would realize by increasing its class and school size. Shalvey and Darwish took a hard look at the data and reflected on what was most critical to the educational model and outcomes they hoped to achieve. While both valued smaller class sizes and the individual attention they facilitate, they felt that the Aspire model compensated for more kids by having longer class sessions, personalized learning plans and interactive exercises. They decided to increase the class size from 25 to 29 for all grade levels above third grade (special class size reduction funding is available for K-3).[11]

When it came to the size of the school itself, however, Shalvey and Darwish both felt that an educational model—no matter how effective—could not make up for the feeling of community that develops in a small school. Their experience told them that once a school got to be larger than 350 to 400 kids, it was no longer possible to hold the personal network of faculty and students together. Thus they ultimately set their school size target at 356.

The second piece of the puzzle was for Aspire to consider the cost of the proposed organizational structure. The team analyzed the cost and timing associated with each position. They quickly realized that the picture emerging was financially unworkable. They went back to the staffing model to see where they could scale back or delay the hiring of new staff until more schools (and therefore more revenue) entered the system.

There is no easy way to do this work. Lee and Darwish sat in a room together, red pens in hand, going through position by position to see where trade-offs could be made. Together they thought about what was required to achieve high quality and found creative ways to delay the hiring of staff, such as initially having one person cover more than one region. This collaborative approach made it much easier to reach a consensus, as each could see the give and take the other was making. Ultimately, they created an organizational plan that supported Aspire’s strategy while working within its financial reality.

Making Changes and Moving Forward

As of December 2005, Aspire was making strong progress on its expansion plans. The organization opened its first LA school in the fall of 2005 and will open two more there next year. It has continued to grow its presence in its focus geographies of Oakland and Stockton, opening a total of three new schools in these districts.

This growth has not come at the expense of quality. To the contrary, Aspire’s established schools have achieved remarkable performance gains. In the 2004-05 school year, every Aspire school exceeded its state API growth target, improving an average of 50 points per school as compared with the statewide average improvement of 20 points.

The organization is beginning to migrate to a regional structure, having hired a Central Valley regional vice president. An experienced Aspire school principal has relocated temporarily to LA to serve as the LA coordinator and Aspire’s chief academic officer is doing double duty as the Bay Area regional vice president; both will remain in these transitional roles until there are enough schools to justify full-time regional vice presidents.

However, this transition has not been without its challenges. Given the organization’s relatively small current scale, many of the regional positions have been filled by staff who also play organization-wide functional roles. For example, the Bay Area regional vice president is also Aspire’s chief academic officer and the Central Valley regional vice president provides secondary school expertise to the organization. As a result, capitalizing on staff members’ functional expertise has become more difficult. Shalvey sees this as the next big challenge for the organization to solve as it continues to refine its approach to supporting its growing network of schools.

Aspire has begun to see benefits from its cooperative approach with districts. In a major boon to Aspire’s financial situation, the Lodi Unified School District offered to take over debt service related to the construction of Aspire’s first schools. The depth of cooperation has increased from there, with Lodi asking Aspire to build a new school. Lodi also has supported Aspire’s efforts to create its own special education programming rather than having to purchase those expensive services from the district. Ultimately it is this kind of partnership with districts, coupled with the high level of performance that Aspire’s schools have been able to achieve, that Aspire believes will lead to improved education for kids through out the state.