The Bayview Hunters Point and Visitacion Valley neighborhoods in the distant southeastern edge of San Francisco have a storied history. Originally settled by working-class immigrant families, the neighborhoods underwent a dramatic transformation in the 1940s. World War II spurred demand for workers at the area's numerous industrial facilities and large naval shipyard. African Americans from the South responded to the need and emigrated in large numbers, ballooning San Francisco's African American population by 600% between 1940 and 1945. This large influx combined with rampant housing discrimination gave rise to highly concentrated African American neighborhoods.

The post-war era saw a rapid decline in employment and economic vitality, punctuated by the shipyard's closure in 1974. With jobs disappearing and investment focused elsewhere, the neighborhoods gradually became islands of poverty, largely hidden away from an otherwise affluent city. Over the years, periodic attempts were made to address poverty and declining conditions in the area. Each effort recorded the situation in the neighborhoods and laid out an elaborate strategy to make progress. These attempts, while well-intentioned, failed to create lasting change.

Recently, however, a new force of change has come to the neighborhoods: economic redevelopment. This time around, the economic forces driving San Francisco's prosperity have made their way down to the southeastern section of the city. A commuter rail service soon will connect it to the financial district. The old shipyard land will be the site of affordable and market-rate housing as well as a commercial center. A new San Francisco 49ers stadium is expected to be the centerpiece for mixed-use development in the area. All told, more than $1 billion of redevelopment efforts are slated for the near term.

This influx of investment represents a huge opportunity for the neighborhoods. It also presents a huge challenge. Will current residents benefit and capture the opportunities, or will they be pushed aside by the market forces of economic redevelopment?

An opportunity for change

In 2004 San Francisco's newly elected Mayor Gavin Newsom and his senior leadership team saw the surge in economic redevelopment activity as a chance to make good on the City's unfulfilled promises to its southeastern neighborhoods. During his campaign, Mayor Newsom made a pledge to create opportunities for the families and children that resided in them. Once elected, he made carrying through on that pledge a priority of his administration. He recognized that the stakes were high. Another failed start could mean the permanent loss of families, particularly minority, from San Francisco.

Mayor Newsom and his team wanted to send a clear message: This effort would be different from those of the past, and everyone's expectations needed to rise. Community residents had to expect more, and service providers had to change the way they operate.

The Mayor's team began by learning more about the situation in the neighborhoods from the residents themselves. A citywide survey, Project Connect, was launched. Representatives from the Mayor's Office went door-to-door and asked residents which services were most important to them and how well those services were being provided. Jobs, safety, and childcare surfaced as critically important needs for which existing services offerings were woefully inadequate.

The Mayor's team then quickly went to work to raise expectations and build momentum. For example, the Mayor's Office engaged with residents of the Alice Griffith/Double Rock housing development to set priorities and create an action plan on which the City could deliver. Residents expressed a strong desire for a community center near their homes. The initial plan was to convert an unused apartment into a makeshift center, but the Mayor's team set everyone's sights higher and placed a state-of-the-art green building right in the center of the housing development.

Building on the early efforts to integrate the communities' voice into the City's work, the Mayor's team brought together a cross-section of stakeholders with the goal of developing and implementing a comprehensive plan for change. Between the financial and organizational resources of the City, with its multi-billion dollar annual budget, and local philanthropy, with resources to support innovation and capacity building, the Mayor knew the opportunity for change would be great if only all of the stakeholders—community residents, city agencies, community-based organizations, and private philanthropists—could align their efforts around a shared strategy.

And so in 2005 the "Communities of Opportunity" initiative was born—its launch marked by an in-depth business planning process. With the support of a group of local foundations, the City engaged the Bridgespan Group to help them address the core questions Communities of Opportunity faced:

- What are the specific conditions in the communities today and what do they need to be?

- What strategy will allow for this transformation?

- How can the various stakeholders align to translate the strategy into action?

- How should the plan be implemented, balancing the desire for clear direction and the need to incorporate real-time learning along the way?

A steering committee, consisting of the heads of 15 city agencies, county agencies, and San Francisco offices of federal agencies, was established to oversee the project and coordinate the agencies' efforts. In parallel, a core group of Bay Area foundations came together to provide input and build momentum for the work among the philanthropic community.

Understanding current community conditions and setting goals

Within the context of planning for major new housing and economic development opportunities, the team sought a way to reorient and align the efforts of city agencies, city-funded community-based organizations (CBOs), and private philanthropy. To ground this work, they would need a detailed view of the communities' needs. The team had the advantage of being able to draw on an in-depth study the City's Human Service Agency recently had conducted of children from all over San Francisco. The Agency looked across agency silos and combined data from various systems of care: mental health, juvenile justice, and foster care. It was the first time such a comprehensive view had been constructed.

Two insights emerged. First, a high proportion of children were interacting with more than one of these systems. Second, service recipients were geographically concentrated around seven street corners (dubbed the "Seven Corners"). A hypothesis took shape: A big part of Communities of Opportunity's solution might lie in better coordinating services delivered to the children and families clustered around the Seven Corners.

The early findings provided Communities of Opportunity with its initial direction and piqued the team's interest in learning more. In-depth, cross-cutting data of this sort could help the team design a revitalization strategy that custom fit the communities' specific conditions. Just as importantly, it could provide an invaluable basis for setting clear goals and measuring progress.

To build a strong fact base, the team embarked on a three-step process: defining Communities of Opportunity's geographic boundaries, describing the conditions within the communities, and developing a deep understanding of the services and programs currently available to residents.

Defining the communities

Communities of Opportunity was not conceived of as a broad effort across a large population. Rather, it was intended to tackle the complex needs of the 2% of San Francisco's residents who lived in its isolated southeastern neighborhoods. As Deputy Director of Mayor's Office of Community Development Fred Blackwell stated, "To really gain traction, we need to focus on the most disadvantaged neighborhoods, flood them with supports, and provide them opportunities to become self-sufficient."

The City decided to pilot this narrowly-focused, neighborhood-level approach in four of the Seven Corners—those located in Bayview Hunters Point and Visitacion Valley: Hunters Point, Hunters View, Alice Griffith, and Sunnydale. These areas came to be known as "nodes."

The team mapped out exact boundaries for each node and then used census data to determine how many people resided in them. The relevant census tracts contained approximately 15,000 people—2,600 families with 5,800 children under 18. While this group constituted a small fraction of San Francisco's overall population, it represented a disproportionate share of the individuals in its human services, public health, and criminal justice systems.

Describing the community conditions

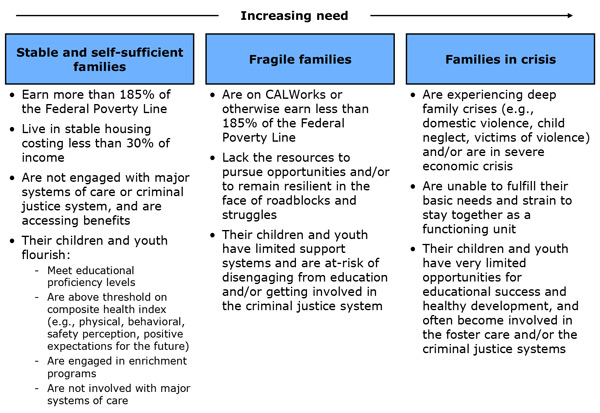

With the place and people defined, the next step was to develop a thorough, data-driven understanding of the conditions the communities faced. One approach the team used was to construct a family-based snapshot. How many families were in chronic crisis? How many were in a fragile state? How many were self-sufficient? (Exhibit A contains the definitions the team used to differentiate family needs.)

Exhibit A: Definitions of family groupings

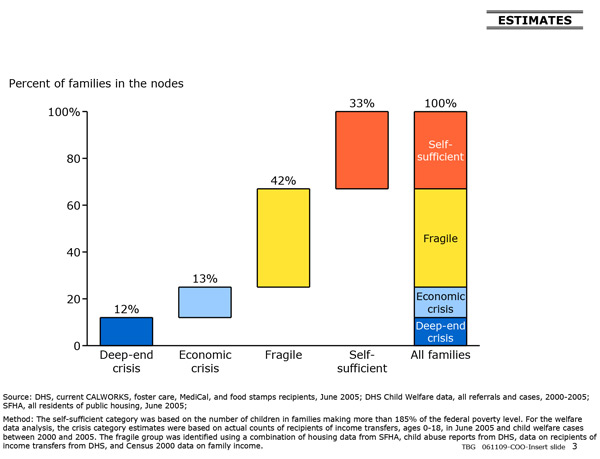

The results were sobering. Fully a quarter were in some form of economic or family crisis. Another 40% were highly fragile—unlikely to be able to recover from the stressors that low-income families often encounter. Only the remaining third met a relatively low standard for self-sufficiency. (See Exhibit B.)

Exhibit B: Node families on the spectrum from chronic crisis to self-sufficiency

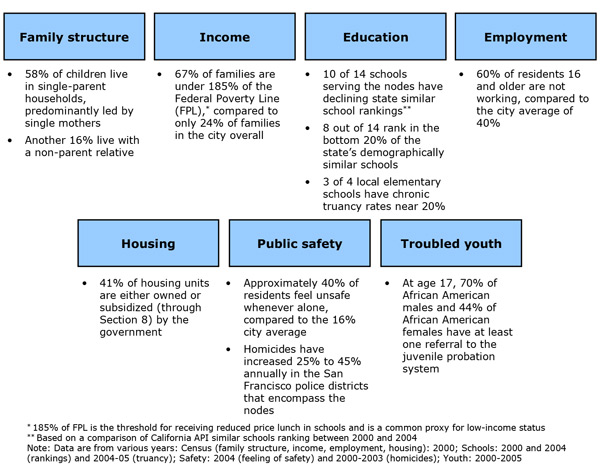

What, then, were the specific conditions that were giving rise to so many fragile and chronically in crisis families? Building off of the Seven Corners analysis, the team collected data on nearly every dimension of human need. On each of these dimensions, the communities were massively disadvantaged, both in absolute terms and as compared to San Francisco as a whole.

Shown comprehensively in Exhibit C, the data was stark. A full two-thirds of families had incomes under 185% of the Federal Poverty Line (a common proxy for low-income status), as compared to a city-wide rate of 24%. Youth were not succeeding in this environment: By age 17, 70% of African American males and 44% of African American females had had at least one referral to the juvenile probation system. These statistics painted a clear picture of a community with undeniable levels of pain and suffering.

Exhibit C: Sample of community conditions in the nodes

When the steering committee met to review all this data, the effect was catalytic. The information had the hoped-for unifying effect on the various stakeholders, making it clear to all that the neighborhoods were not facing just a youth problem, nor a jobs problem, nor an infrastructure problem, but rather something much more profound and systemic. Sylvia Yee of the Haas Jr. Fund captured the sentiment in the room: "It got the group collectively away from thinking about the communities and families only through their respective lenses, and helped them realize that it would demand an unprecedented level of cross-cutting integration to break the vicious cycle of poverty."

Mayor Newsom spoke of the need for a fundamental culture change within the City: "No longer could the government be content with doing its best to reduce disparities. Instead, we need to recognize and deliver on the rights of residents to their fair share of the opportunities available in San Francisco."

Trent Rhorer, Director of the City's Human Services Agency, remarked, "We are a major force in these communities. These residents are the primary clients for our services, and what we've been doing is not working for them. We need to rethink every aspect of our work, particularly how we work together."

Understanding current programs and services

As Rhorer alluded to, there was no shortage of social programs and services intended to address these numerous challenges, yet the bleak conditions remained. To get to the bottom of this paradox (and to avoid repeating past mistakes), the team investigated where the resources were going and to what effect. Team members collected data about funding and participation levels. They complemented this quantitative view with qualitative data gleaned from interviewing service providers.

The picture that emerged was eye-opening. The public resource pool available to create opportunities for families in these neighborhoods was far larger than anyone had imagined. The City was spending nearly $100 million annually—directly to families and through CBOs—to serve children and families in the two ZIP codes that encompassed the nodes (an area about four times the nodes' size). The money was going towards mandated interventions such as juvenile justice and foster care; public benefits; and the provision of other social services (e.g., child care, after-school programs).

Despite all the programs and money spent, the impact of the City's efforts was weak. Service accessibility was a major issue. For example, nearly 60% of infants and toddlers eligible for childcare subsidies were not enrolled in that program. Likewise, teen participation in after-school programs was anemic, with only about 15% of youth accessing the full set of youth programming available to them.

Service provider interviews shed further light on the problems. Several providers indicated that location precluded potential service recipients from attending programs, often because of gang-related turf issues. Many programs required residents to travel out of their neighborhoods, putting their personal safety at risk if they needed to return after dark.

Service provider ineffectiveness also surfaced as a major issue, with the City's approach to working with providers being a contributing factor. Most of the organizations in the neighborhoods ran on small budgets with limited capabilities in general and financial management. Training and retaining quality staff was often a challenge, as was tracking expenses to ensure funds were spent effectively. Almost all of organizations lacked data on the results of their work with families and children.

The City contributed to this situation by spreading grants broadly with little consideration of each organization's capacity to achieve results and by severely limiting funding for infrastructure and management. Moreover, the City's various agencies represented at least 80% of the CBOs' funding, but failed to coordinate internally. A City grants manager summarized the resulting problems: "A lot of CBO programs are under-enrolled, some are unresponsive to the communities, some are simply mismanaged, but they keep getting funded year after year. De-funding some of these would send a powerful message. However, when our agency defunds, another agency is likely to fill the void."

Indeed, the CBOs themselves were frustrated by their inability to achieve positive outcomes with residents. While they complained of resource gaps, it also was clear that many lacked the skills required to work effectively with high-need residents. Additionally, they rarely had the relationships with other service providers that were necessary to address a resident's full set of needs. The executive director of one employment-focused organization characterized the challenge: "Many of our clients need support to deal with criminal records or substance dependencies. We often have no way to get them into the right programs and therefore can't help them find jobs." Addressing these capability gaps in the CBOs would be a vital priority in creating and sustaining positive change.

Setting goals for families

With Communities of Opportunities' starting point now in focus, it was time to develop a picture of what success would look like. Getting everyone moving in the same direction would require clear goals for progress. Team members knew they wanted families to achieve self-sufficiency, but they also knew it would not be realistic to expect this outcome for every family in the near term. They needed to set goals that were ambitious yet realistic.

The early analysis of the family conditions served as the basis for several planning team and steering committee discussions. The group established consensus around two overarching goals:

- The majority of the communities' families are self-sufficient: This level of self-sufficiency would help create an environment for families in which the community balance favors stability and can provide the types of supports that families in other communities rely on for resilience.

- The proportion of families in crisis does not exceed 10%: Families in crisis experience trouble themselves and also have negative effects on their surrounding communities. Helping them stabilize would have positive effects both on the families' individual situations as well as on overall community stability and vitality.

These simple goals aligned all stakeholders at the table: the Mayor and his senior staff, various agency heads across the city, and foundation partners. They also reinforced the degree of culture change that would be required to succeed. All involved, from the City to its partners to the community residents, would have to maintain high expectations of success to reach them.

The goal statements evoked a ladder metaphor which became the dominant description of what the collective aspired to achieve. Communities of Opportunity would be about building "ladders" for families to "climb" to self-sufficiency. It would help those families in crisis stabilize, and those in fragile situations become more resilient and self-sufficient. Furthermore, it would help to bring about the social networks, physical infrastructure, and safe environment necessary to make those ladders an upwardly spiraling stairway.

The essential strategy to drive change

The planning team next turned its attention to those ladders: What strategy would provide families with the supports they needed to escape poverty and crisis and reach for opportunities and a better life? To define the strategy, the team relied on four critical sources of input.

- Facilitated inter-agency problem-solving sessions: City agencies were to be central to the implementation of the strategy. Accordingly, agency leaders needed to be involved in the strategy development process. At both the agency director and program levels, teams dedicated to particular program areas (e.g., education, housing) were brought together to create crossdepartmental solutions.

- Community engagement: A "Community Voice" process, facilitated by the National Community Development Institute, provided input and feedback via meetings in each node—gatherings during which the team solicited community input on residents' most important concerns and on emerging solutions.

- Focused review of promising models from across the country: Hoping to learn from others' experience, the team conducted a review of previous and current neighborhood-change efforts and also examined promising models for specific programmatic activities (e.g., violence reduction).

- Expert interviews and a discussion panel: The team periodically asked people who had demonstrated expertise in efforts similar to parts or the whole of Communities of Opportunity to vet the strategy and initiative options as they emerged.

The pursuit and integration of these streams of work was intense and highly iterative. The planning team met every other week to drive the strategy forward. The emerging strategy was vetted by the full steering committee every six weeks, including two half-day workshops geared around defining integrated approaches in major programmatic areas. The local foundation partners served a similar role of review and critique at several times during the process.

The hours committed to the process paid off, with the end result being a diverse group of stakeholders aligned around a common plan for action. Three core tenets defined the plan.

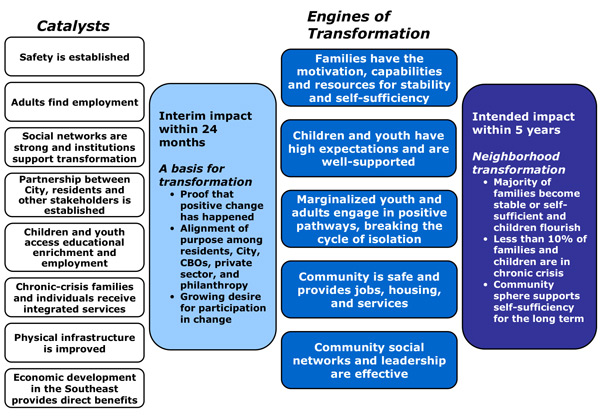

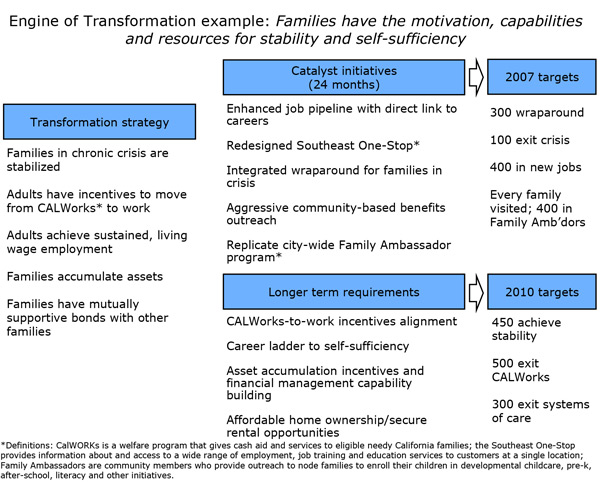

1) Create a basic framework for long-term transformation that provides guide posts for change but does not pre-define the entire sequence of initiatives.During the inter-agency problem-solving sessions, it became clear that the planning team could not possibly prescribe all the activities that would be necessary to achieve Communities of Opportunity's ambitious goals. They would have to allow for learning and adjustment along the way. That did not mean, however, that there would be no structure to Communities of Opportunity's approach. Structure would come from agreeing on the key conditions that the team would jointly work on creating. These "engines of transformation" would result in:

- Families having the motivation, capabilities, and resources for stability and self-sufficiency;

- Children and youth having high expectations and being well-supported;

- Marginalized youth and adults engaging in positive pathways, breaking the cycle of isolation;

- Communities that are safe and provide jobs, housing, and services;

- Community social networks and leadership that are effective.

Communities of Opportunity would prioritize among the many activities it could pursue according to each initiative's potential to contribute to the engines of transformation.

2) Build a platform for change first.

Given the neighborhoods' history and their current conditions, it would be impossible to jump immediately into a full-fledged transformation campaign. The ignition key simply had been worn down over the years by one failed effort after another. At every Community Voice meeting, residents exhibited a strong skepticism that Communities of Opportunity would be any different than the numerous plans that had come before. City staff members likewise expressed reluctance to embrace Communities of Opportunity wholeheartedly. As one staff member commented, "My shelf is full of plans for improving these communities, just sitting there collecting dust. Nobody follows through and nothing gets implemented."

To get beyond this skepticism and demonstrate that things would be different this time, Communities of Opportunity would need to create concrete change in the near term. Community members, city staff, and other stakeholders then would see that change was possible and participate in making it more widespread. Over the first 24 months, the goal of Communities of Opportunity would be to create a "basis for transformation."

3) Prioritize the changes that would need to occur in the very short-term to create and sustain broad momentum for change.

Small, but quick gains for the community would be a must. Visible change would have to occur in the neighborhoods in the coming weeks and months, to begin to break through the skepticism. But what kinds of change and to what ends? A set of "catalyst" programs was in order.

In selecting the catalysts, the team considered the following criteria:

- Important to long-term change: Would lay the foundation for the engines of transformation and create real change for families in the nodes;

- Visible: Would be seen by many residents, helping to convey the idea the Communities of Opportunity would improve their quality of life;

- Symbolic: Would prove that change is possible and raise expectations of community members and City staff alike;

- Achievable: Would have a high likelihood of implementation success.

The Community Voice meetings were a crucial source of input here. For example, at one meeting at the Alice Griffith public housing complex, public safety was top of mind. Nearly 80% of the attendees elected to join a discussion about safety concerns, and a vigorous dialogue with local San Francisco police officers ensued. Safety was clearly a high-priority issue for the community. While safety issues cannot be solved overnight, the City could improve public lighting and install safety cameras in short order. Making these changes happen could have catalytic potential.

Eight categories of catalysts, including public safety, were named, with specific initiatives identified within each. Job creation catalysts would aim to provide residents with real job opportunities; a key initiative here would be to link residents quickly with jobs with the City or in City-funded projects. Catalysts connecting the neighborhoods to San Francisco's broader economic redevelopment initiatives also were given heavy weight, to make sure that residents could take full advantage of these emerging opportunities.

And so a comprehensive theory of change for Communities of Opportunity was born, with catalysts feeding into 24-month interim impact goals to create the basis of transformation, and then engines of transformation firing towards clear five-year goals (see Exhibit D). Going one level deeper, the team described each engine of transformation in more detail, specifying the changes Communities of Opportunity would work to bring about in the near and longer term and establishing metrics that would be used to track progress along the way. (See Exhibit E for the family-based engine example.)

Exhibit D: Theory of Change for Communities of Opportunity

Exhibit E: Strategy for family-focused engine of transformation

Translating the strategy into action

With the strategy construct in place, the team turned its attention towards matters of implementing and sustaining Communities of Opportunity. They focused on three levers: leadership, collaboration, and accountability.

Leadership: Guiding Communities of Opportunity

Having strong leadership would be essential at both the City and community levels. City leadership would have to begin with the Mayor. His sustained focus on Communities of Opportunity would be essential if the initiative were to create the desired change. He would need to ensure continued alignment of City leadership; to help build coalitions among the various stakeholders; and to allow for the change to be institutionalized at the City level.

Beyond the Mayor's efforts, strong day-to-day City stewardship would be critical across a broad range of agencies. The Communities of Opportunity steering committee would need to play a continued role in guiding the process and ensuring that their agencies followed through on the change agenda. The director of Communities of Opportunity would need to be a senior staff member with the vision and willingness to partner with City leaders to achieve major change in how the City operates. The director also would need to have pre-established relationships with community members and to command their respect. Dwayne Jones, then the Director of Mayor's Office of Community Development and the former executive director of a local young adult job-training nonprofit, was passionate about the project, and the Mayor tapped him to assume the director role.

Community members also would have to assume key leadership roles, particularly as Communities of Opportunity became more established. The City was well aware that governing administrations came and went. In sharp contrast, Communities of Opportunity could not be a short-term effort; it would require sustained community attention to reach its goals. Too many past plans never gained community ownership and lost their ability to drive change. The community ultimately would need to own and lead Communities of Opportunity if it were to be truly sustainable.

During the planning process, community members engaged through the Community Voice work by serving on design teams and helping to organize broader community meetings. To carry forward this community engagement, Communities of Opportunity would pursue multiple avenues. It would launch a Leadership Institute to develop the next generation of community leaders. It would invest resources in building community members' ability to advocate for themselves, thereby magnifying their voices. And it would invest in the local CBOs, addressing capability gaps and helping to make them long-term facilitators of opportunity for the neighborhoods.

Collaboration: New ways of working together

Communities of Opportunity always had been imagined as a collaborative effort. At the very first steering committee meeting, several participants had remarked that they could not remember a previous time when so many department heads had come together to focus on coordinating their efforts. The partnership with a coalition of local foundations was also very unusual. Going forward, Communities of Opportunity would aim to maintain this shared vision through regular and repeated interaction with all major stakeholders. The steering committee would bring together agency heads several times a year. Likewise, a public-private partnership would provide a forum for the joint learning and continued engagement of local foundations. Perhaps most importantly, the communities' input and ownership of Communities of Opportunity would continue to grow.

Consider the various agencies within the city. During the planning process, several departments identified new ways in which they could work together. One example comes from the Department of Human Services, Department of Public Health, and Juvenile Probation Department. The Seven Corners data had convinced the heads of these agencies that significant overlap existed among the families each served, and that gains could be realized by coordinating their service delivery efforts. As such, they began to take steps towards introducing “wrap-around” programs that consolidated the multiple case managers and plans into a single point of contact and a family-driven plan of care.

For City and local foundation partners, the Communities of Opportunity business plan would serve as the guiding framework for aligning their investments in the communities. A formal collaborative of funders was established with a signed memorandum of understanding from the City. The collaborative would pool funding to provide financial support to Communities of Opportunity at regular intervals, provided the plan remained on track. In the initial stages, the City would combine public resources with private funding to conduct pilot projects and support transitional activities in agencies. The private funding would provide important resources for innovation and demonstration to enable a permanent shift in public service delivery in the communities.

Finally, the City would continue to enhance its collaboration with residents. Work here would build on initial progress made at the Alice Griffith housing project and encompass projects with residents and parent associations in each neighborhood.

Accountability: Focus on creating real outcomes

Communities of Opportunity stood for a new kind of accountability, one with a clear focus on families and communities. The effort would not be committed to specific means—rather, specific ends. The planning process identified high-potential initiatives for driving change, but also recognized the need to incorporate real-time learning. Those initiatives that were not creating the desired change either would be reconfigured or eliminated altogether.

To make this accountability real, a new Communities of Opportunity program office would devise a system to monitor the initiatives and track their results systematically. The information would allow Communities of Opportunity to make strategic decisions dynamically: to accelerate those initiatives that were succeeding; to identify—and end—those initiatives that were failing; and to identify gaps so that new initiatives could be conceptualized and launched to fill them. The program office would develop a dashboard for sharing information with Communities of Opportunity stakeholders, making the level of progress against the articulated goals transparent to all.

Getting to the hard work of implementation

With strategy in hand, the truly hard work has begun: implementing the plan. City leadership has focused on implementing a selected set of items to sustain the momentum generated during the planning phase.

The Communities of Opportunity office is now in operation and City agencies have begun to realign their activities to implement the catalysts. A core team has been hired, including a deputy director, to coordinate implementation. Beyond the City, Communities of Opportunity is creating and reinforcing connections to community residents. A team of 18 outreach workers (all residents of the communities) has been assembled and trained to become coordinators in their communities.

High-priority catalyst initiatives are making the transition from planning to launch. The Mayor and Board of Supervisors approved funding for a public safety initiative in March that provided for improving lighting in the communities, placing safety cameras in hot spots, and increasing youth employment opportunities. Over the summer, a nationally-recognized program on African-American culture, Heritage Camp, was offered to children and their parents.

In another catalyst initiative, the Communities of Opportunity team worked with the Mayor's office on a project to eliminate the digital divide in public housing. Project Tech Connect turned a request by residents for a computer lab into an opportunity to earn free home computers that would be networked to high speed WiFi in the Alice Griffith development, making it the first public housing development in the country to be suffused with Internet connectivity.

On the financial front, the team has worked steadfastly to line up resources for near-term priorities. They have achieved success in both the City and philanthropic spheres. The City's agencies have allocated several million dollars of program funding to support the first year of work in the communities. Local foundations have committed nearly $2 million to a pooled fund to help launch the initiative and are helping to raise additional private dollars. Many of the foundations will consider providing additional funding for specific projects aligned with their grant priorities. Foundation partners also have committed to take part in working groups on the initiative's priority areas to lend their expertise.

The Mayor hosted the first annual Stadium-to-Stadium race in August that wound through Bayview Hunters-Point to build momentum and support for Communities of Opportunity. And while activities have been ongoing in the communities from more than two years now, Communities of Opportunity became official at a launch event at 49ers Stadium this past October 3rd. The Mayor, his team, and community residents joined in a celebration of a new beginning for the neighborhoods.

There are many challenges ahead, lessons to learn about what works and what doesn't, but the work continues with a determination to create a new beginning for San Francisco's southeast...