Footwork Trust, a London-based charity that facilitates locally led neighborhood transformation through support programs and grants, shares a brick building with a clock-making workshop. “We’re acutely aware of time,” muses Naomi Rubbra, Footwork’s CEO. “As a young organization, I think we move exceptionally fast—collaborating at the pace and scale required for communities to create socially just and climate-resilient places.”

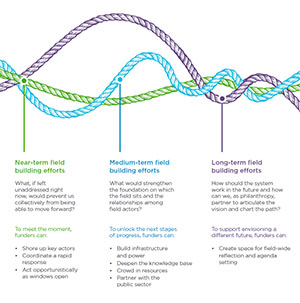

In its field-building work, Footwork operates with multiple timescales in mind—it works to unlock impact across near-, medium-, and long-term periods. Its work of “community asset development” involves shifting property ownership into local control—often through community land trusts, mutual aid networks, and other organizations. The ultimate goal is to reconnect people and place, building thriving communities in neighborhoods that are feeling the pressure of lost public services, empty shops, speculative investment, and absentee landlords.

Footwork identifies and convenes emerging local leaders—community asset developers—and provides them with hands-on mentorship, expertise, training, and unrestricted grants to nurture their ideas. Rubbra calls Footwork support “a strategic cuddle, of sorts.” Through its People and Place program, it is weaving a network of these community leaders. By building a knowledge base of locally led community transformation, it helps shape the field of sustainable regeneration across the United Kingdom.

“These community innovators may be here to resolve homelessness, climate risks, or social isolation,” says Rubbra. “But to do that, they need to get some power, some ownership, some autonomy over their place because the current model of ownership and dynamics between stakeholders is not working.”

We met Rubbra at the Skoll World Forum in Oxford this past spring as political and economic volatility reverberated from the United States around the world. We had convened a group of field-building funders to learn more about the challenges and opportunities they saw in this moment. Sentiments ranged from cautiously optimistic to undeniably distressed. And many discussed timescales: how this moment has created a broader set of both needs, some quite urgent, and possible long-term solutions for so many fields, contributing to a sense of paralysis.

Indeed, in moments like this—when the ground feels shaky—a long-view, field-building approach is not just relevant—it’s necessary.1 An extended time horizon allows space to envision new possibilities and plan proactive approaches. At the same time, this can feel distant from the urgency of the moment—a time to meet immediate needs and seize windows of opportunity. Many field-building funders today are navigating these overlapping timescales.

The Anatomy of Field Building

Field-building funders invest in one or more of six key characteristics of a field: knowledge base, actors, field-level agenda, adaptive infrastructure, resources, and public-sector systems. We explored these characteristics through a collection of case studies in our earlier research, Field Building for Population-Level Change. In the five-plus years since, The Bridgespan Group has been in community with over 100 field-building funders and field-catalyst organizations pursuing population-level change.

Field building is challenging. Population-level social problems—such as teen smoking—are complex, and the environment is constantly changing. Often, there are differing perspectives on what it takes to advance a field. And the field’s needs might not match how funders typically approach it.

Our analysis of dozens of fields, combined with our experience as advisors to field-building funders and field catalysts, has demonstrated the critical contributions of field building to population-level change. Consider the decline in unintended teen pregnancy rates or the progress towards malaria eradication. Both hinged on committed, effective, and persistent field-building efforts.

Many field-building funders excel at identifying emerging or unrecognized leaders and supporting them with direct financial resources, capacity development, and connections. Typically, collaboration across a diverse range of actors—research, policy, practice, organizing/mobilizing, intermediation, and funding—plays complementary roles in driving field-building efforts. Importantly, not all funders need to be equally engaged across each timescale, and that engagement may shift over time.

The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s (RWJF) decades-long investment in tobacco cessation offers a powerful illustration of a field-building funder working across multiple timescales. That work began in the early ’90s with support for policy analysis and state-level coalition-building. Five years later, however, teen smoking rates had jumped in the United States,2 and RWJF realized that its policy efforts were valuable but insufficient to move the needle nationally.3

Rather than shy away from the challenge, RWJF leaned into a multiple-timescale strategy. It built relationships with a broad range of actors—grassroots advocates, funders, civic associations, White House advisors, even tobacco farmers—to help them identify their entry points and define the contributions they could make to advance the effort. RWJF funded narrative change work and galvanized cross-partisan public support, which paid near-term dividends that enabled the field to do the long-term work of setting shared goals.

As a bridge into the long-term vision, RWJF helped launch the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids, which provided the adaptive infrastructure and connective tissue needed to lead the work and build momentum through wins like state taxes and tighter US Food and Drug Administration regulations on tobacco products.4 The investments created the conditions for deeper coordination among actors in the field and laid the foundation for RWJF’s long-term strategies to secure durable policy reform and population-level change. Ultimately, the Campaign has contributed to a 94 percent decrease in youth smoking nationally since 1996.5

Field Building in the Near Term

Field-building funders focusing on the near term can quickly and effectively respond to immediate threats and capitalize on distinct opportunities for progress. The animating question that informs this work: What, if left unaddressed right now, would prevent us collectively from being able to move forward?

Shoring up key actors

Funders can be nimble in shoring up anchor partners. The Skoll Foundation, for example, quickly established a “pivot fund” to support grantees affected by cuts to foreign aid in 2025. The fund provided an injection of capital, enabling grantees to sustain their impact while reimagining their work in a shifting landscape.

Nellie Mae Education Foundation (NMEF) sees that building grantee capacity—investing in key actors—is crucial to strengthening the education justice6 ecosystem. To do this, in 2024, NMEF launched a capacity-building accelerator7 for a group of 50 New England-based organizations, including a cohort of advocacy organizations supported by the Schott Foundation. The accelerator aimed to strengthen the ecosystem of youth, educators, parents, and community organizers and organizations that support schools in seeing, understanding, and meeting the unique needs of students.

“As a regional foundation, we are committed to advancing an ecosystem approach to field building by strengthening feedback loops that build will and power at every level to ensure community voice is reflected in decision making,” says Gisele Shorter, president and CEO of NMEF. “Ultimately, we want to support those policies, practices, and budgets that help students to thrive in school and careers of the future.”

Through the accelerator, organizations have clarified strategies, assessed progress and organizational needs, developed leadership effectiveness, and mapped financial resilience plans. NMEF has also been able to track and support grantee durability and, importantly, identify other enabling conditions that could enhance durability over time.

Identifying windows of opportunity

Well-cultivated networks also prepare field builders to take advantage of windows of near-term opportunity. Tanoto Foundation is a leading funder of early childhood education and development (ECED) in Indonesia and China, a complex field with a range of stakeholders, including government agencies, private-sector organizations, NGOs, and community-based organizations. In Indonesia, at least 12 ministries and governmental agencies have programs that touch on ECED, but services are fragmented, says Eddy Henry, head of policy and advocacy at Tanoto Foundation.

“We’ve taken on the role to ensure that this field of early childhood development is built,” he says. “There needs to be more awareness and understanding of the importance of early childhood across the various stakeholders.”

With its unique vantage point and connectivity, Tanoto Foundation helps inform policy and legislation during key windows of opportunity. “We balance both being structured and very strategic, but we also understand that when we talk about policy, sometimes it’s very opportunistic and pragmatic,” says Henry. With each change in government leadership, he adds, there are both challenges and opportunities.

“We can see opportunities to provide direct advocacy for certain leaders who can drive changes much faster,” Henry says. “We were involved in the development of quite a few regulations, including the Law on Maternal and Child Wellbeing [in Indonesia], and the mid- and long-term national development plans. During the last general election, we were involved in ensuring that ECED is on the government’s priority agenda and was featured as a topic in the presidential debate.” Working with the National Institute for Public Administration, Tanoto Foundation helped train hundreds of civil-service policy analysts in using data and evidence to design and evaluate public service policies, particularly in the education and health sectors.

Field Building in the Medium Term

Medium-term field building strengthens field characteristics that help unlock the next stages of progress over a three- to seven-year time horizon. Funders interested in field building in the medium term can use this animating question to inform their work: What would strengthen the foundation on which the field sits and the relationships among field actors?

Building infrastructure and power

Medium-term field building requires infrastructure and power building. Both infrastructure and power building create the connective tissue that coordinates and connects efforts from different organizations—and government agencies—making them more than the sum of their parts.

The Raikes Foundation’s work to end youth homelessness in Washington State exemplifies this aspect of field building. One way Raikes approaches this goal is by investing in organizations that empower youth who have experienced homelessness.

It does this through its support for initiatives such as the WA Coalition for Homeless Youth Advocacy, a statewide partnership of providers, funders, and advocates that educates policymakers on the state’s youth homelessness problem. Another initiative the Raikes Foundation supports is the Mockingbird Society, which develops and supports youth leaders to advocate for better policies. Furthermore, the Raikes Foundation supports organizations that aim to keep youth stably housed by developing and implementing prevention strategies across school, foster care, legal, and behavioral health settings.

The foundation also recognized that accurate data is critical to an integrated solution. It supports the work of agencies and organizations, such as the state’s Office of Homeless Youth, as well as nonprofits like Building Changes and Community Solutions, to ensure that all partners and agencies have access to quality data. By supporting this statewide infrastructure, the Raikes Foundation’s investments have contributed to a remarkable 40 percent drop in youth homelessness from 2016 to 2022, a 37 percent increase (over nine years) in the graduation rate for students experiencing homelessness, and a 29 percent reduction (over five years) in homelessness for youth leaving public systems of care.8

Building the knowledge base

Medium-term steps in field-building work also include building field-wide research and knowledge. Funders can commission new research to fill critical gaps in the field, support narrative change and storytelling work to shift perceptions of an issue, and translate knowledge across stakeholder groups.

Tanoto Foundation prioritizes the development of what it calls “knowledge hubs”—it convenes ECED stakeholders from academia, development agencies, practitioners, and media to inventory existing knowledge and elevate the knowledge gaps that need the most funding. “We aim to generate evidence that can be used in advocacy for system strengthening, policy reforms, and raising awareness,” Henry says.

As a field’s knowledge base grows and incorporates an increasingly diverse set of perspectives, this knowledge provides the data and information needed to design, implement, and adapt effective approaches. It also serves as a common reference point for the field’s actors, helping to harmonize their efforts.

Crowding in resources

With the medium term in mind, field-building funders can consider deploying both financial and nonfinancial resources. This could mean facilitating introductions between funders and organizations, as well as developing on-ramps for new funders through pooled funds, time-bound partnerships, and light-touch learning opportunities.

For example, in its work across Indonesia to prevent stunting in children, Tanoto Foundation “crowds in” additional resources. Alongside the Gates Foundation, the foundation is a founding donor of the World Bank’s Multi Donor Trust Fund for the Indonesian Human Capital Acceleration, which catalyzed $14.6 billion in government spending between 2020 and 2024 on stunting prevention programs. The result: a reduction in stunting from nearly 28 percent in 2019 to nearly 20 percent in 2024.9

“We work with other donors, NGOs, and other philanthropic organizations as well on the stunting reduction program,” Tanoto Foundation’s Henry says. “We are in the process of establishing an ECED collaborative to pull in a group of funders, both philanthropic organizations and corporate foundations.”

Partnering with the public sector

Partnerships with the public sector are often crucial for field builders addressing deeply entrenched social problems. A funder could invest in joint policy design, fellowships, and shared data platforms to strengthen relationships between field actors and government stakeholders. It could also support policy-advocacy infrastructure by resourcing coalitions and legal advisors to engage effectively in policy development.

As noted above, Tanoto Foundation works with government officials to engage in policy dialogue that will improve ECED outcomes. Its ECED Council also serves as a mechanism to facilitate public-sector buy-in and co-ownership. “This allows the government to see the other players and see the investment in the field,” says Michael Susanto, head of Early Childhood Education and Development at the Tanoto Foundation. “It also gives the organizations a platform where they can showcase their work and creates a space for us to work together for a common cause.”

Field Building in the Long Term

Funders engaged in long-term field-building support efforts to envision a different future. The animating questions that inform this work are: How should the system work in the future? How can we, as philanthropy, partner to articulate the vision and chart the path?

Field-building funders are adept at painting a picture of what’s possible—looking farther out on the time horizon than is typical in philanthropy. They step back from day-to-day work to create space for ongoing, field-wide reflection, envisioning, and planning. In doing so, they drive toward systems change while continuing to invest in infrastructure to sustain progress as conditions evolve.

Field-building funders can consider several long-term investments to support field-level agenda setting. They can fund organizations and actors that engage working groups and coalitions to shape a field’s direction. They can invest in spaces that enable field leaders to align on long-term goals. They can also help develop shared evaluation frameworks to assess progress over time and ensure peer funders remain coordinated rather than working at cross-purposes.10

In 2020, over a dozen funders—including the Pisces Foundation, the Walton Family Foundation, and the William & Flora Hewlett Foundation—supported the launch of Mosaic, a pooled fund that invests in movement infrastructure across the fields of climate, conservation, and environmental health and justice. Mosaic supports the connectivity, shared tools, and alignment across people, geographies, and issues needed to build power for durable, population-scale wins on environmental issues. It has deployed $32 million through 418 collaborative grants—reaching roughly one-quarter of the US environmental field.

“Mosaic is resourcing work in the US to build bridges across differences—geographic, ideological, political, you name it,” says Eva Hernandez, executive director of Mosaic, “so that we can have a powerful, broad-based civil society front to protect our climate; conserve lands, waters, and wildlife; and support thriving communities.”

With its big-tent approach, Mosaic has brought together national, state, and regional organizations alongside grassroots, justice-forward, and community-based organizations. Research it conducted in 2025 also points to a clear need for increased investment to strengthen essential power-building in the environmental movement.11

“As concepts like climate change and clean energy become increasingly politicized, the work of maintaining and expanding our tent becomes more challenging and more urgent,” Hernandez wrote recently in Chronicle of Philanthropy. “But it is happening in ways that should inspire hope and philanthropic investment.”

Population-level Change Needs Field-building Funders

Field-building funders work across diverse issue areas, contexts, and geographies. Our research shows that they also recognize that in their work to achieve systems change, they operate across all timescales. Urgent times require action, and long-term problem solving requires patience and vision—two things that are hard to reconcile but necessary.

“Often the best way to address a crisis is to prevent it in the first place, and that requires thinking about how to shape the future even while addressing the present,” says Jason Morris, environment and climate lead at the Pisces Foundation. There’s been a shift in the dialogue, he says, in which the present urgency is part of a broader consideration of how fields develop to better support common needs and interests. “The amount of conversation in recent years about how we invest in stronger fields—connected, aligned, and more capable—has increased significantly and is accelerating. That bodes well for us all.”

For any field, the weight of right now will always feel dominant. Field-building funders, however, bring the perspective and discipline to work across multiple timescales—a necessity for achieving population change in addressing our biggest social problems.