On July 1, 2008, the Gateway to College National Network, a network of dropout recovery programs developed by Portland Community College (PCC), officially separated from the college to become an independent 501(c)(3). For Laurel Dukehart, former Gateway replication manager and now executive director (ED), the spin off signified the culmination of an intensive year of planning. It also marked the much-anticipated beginning of a new phase in the organization's growth.

What is the Gateway to College National Network?

Gateway serves at-risk youth, ages 16 to 20, who have dropped out of school. Participating students can accumulate high school and college credits simultaneously—enabling them to earn their high school diploma while progressing toward an associate degree or certificate. By fall 2008, the Gateway program will be in place at more than 20 community college sites across the United States. For more information, visit www.gatewaytocollege.org.

This case study explores Gateway's spin-off experience, key process steps, and lessons learned. While it focuses on one organization's path, our hope is that the work of Dukehart and her team will prove illuminating to others considering or executing a similar transition.*

The story is organized around three questions:

- Why spin off? Here we discuss the considerations that led to Gateway's separation from PCC.

- What are the nuts and bolts of setting up your own nonprofit? This section describes the legal process of becoming a 501(c)(3) and the work required to develop an independent infrastructure.

- How will the organization need to evolve? Here we highlight the process of establishing a Board, clarifying decision roles, and other staffing shifts that may be required.

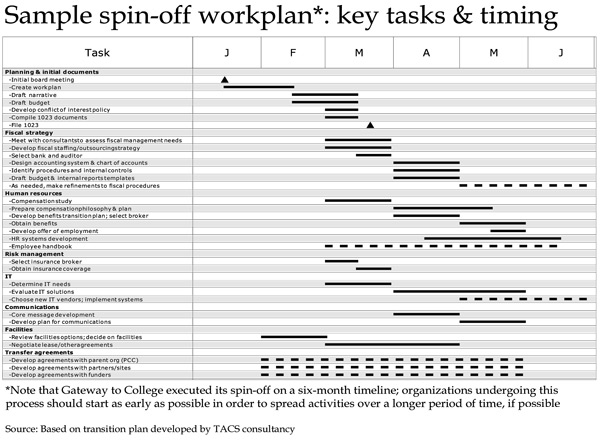

Following the story, the Appendix provides a sample planning calendar outlining key tasks in preparing to transition.

Why spin off?

There are several reasons an existing program may choose to separate from a founding or umbrella institution. In some cases, as the program reaches the end of its "start-up phase," it may have outgrown the sponsoring or incubator parent in terms of size, services, or even physical space. In other cases, missions and/or operations may diverge, requiring a separation.

Key events in Gateway's evolution

2000- Launched program model at Portland Community College

- Began replication planning with support from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation

- Opened first replication sites in California and Maryland

- Opened three sites in Oregon, Texas, and Georgia

- Developed business plan for additional replication

- Opened four sites in Pennsylvania, North Carolina, Massachusetts, and South Carolina

- Opened three sites in Massachusetts, New York, and Texas

- PCC Board voted to approve Gateway's spin-off from the college (October)

- Filed articles of incorporation (December)

- Gateway Board gathered for initial meeting (January)

- Filed 1023 form (April)

- Officially an independent organization! (July)

For Gateway, several factors related to its rapid growth motivated the transition. At one level, the organization was outgrowing PCC's existing systems and structures:

By the spring of 2008, the Gateway Network included sites at 18 community colleges in 12 states. While Dukehart and her team supported the full network, their position within PCC had the potential to create a "first among equals" dynamic that did not reflect the network's aspirations. While PCC had germinated the program and developed many best practices, the vast majority of students were located elsewhere. Gateway wanted each site to engage in peer learning and leadership activities on equal footing.

Although PCC's infrastructure was essential to Gateway's start up and early operation, it was not designed with Gateway in mind. Job descriptions reflected college employee functions—not program staff roles. IT systems assumed data capture within a single institution—not across multiple colleges and states. Gateway had adapted to PCC's infrastructure, but further growth raised the question of whether the Network should continue to replicate the systems and protocols designed by PCC or tailor ones to the Network itself?

In addition, Gateway wanted to take advantage of new opportunities:

- At the time of the spin-off, Gateway was just entering the "expansion phase" of its development. In addition to continuing replication (planned growth from 18 to 50 sites by 2013), the team anticipated investing more heavily in thought leadership and advocacy within the field. Gateway hoped that by advising policymakers and similar programs, it might create a more favorable environment for dropout recovery efforts nationwide. PCC supported these goals, but the college's core business was to provide services to Portland residents—not to replicate educational models or influence policy. It was possible that, in taking a stand on certain issues, Gateway might find itself in conflict with its parent.

- As a program within PCC, Gateway enjoyed the financial benefits of the college's in-kind and administrative supports. But the program's funding model differed significantly from that of the college overall. While PCC is financed by public revenues, Gateway's growth has depended largely on philanthropic support. Because many funders do not give to public or higher education institutions, Gateway's status within PCC significantly narrowed the pool of available philanthropy. Similarly, Gateway had to closely coordinate any fundraising efforts with PCC's grants office. When approaching regional donors, for instance, PCC weighed Gateway's "ask" with those of other PCC departments. In some cases, Gateway's request took a backseat.

Of the factors outlined above, no single factor led Gateway to pursue a spin-off. Rather their collective effect drove the decision.

It's worth noting that a program can face the above challenges and still conclude that the benefits of remaining within a parent outweigh those of spinning off.

- For starters, when it comes to funding, an organization must consider the opportunities available from standalone fundraising versus the cost of losing in-kind support and the challenge of meeting IRS nonprofit guidelines.

- While a parent organization's strategy may not align fully with a program's strategy, the program may benefit greatly from the credibility or institutional knowledge of a more established entity.

- Though inherited back-office systems may not be ideal, building new infrastructure is a significant undertaking and comes with its own costs.

- The spin-off process itself requires investment—in transitional work (legal fees, planning time, etc.) and potentially in long-term capacity (new staff or contracted supports). Dukehart estimates that she and her team spent a full person-year (~2000 hours) managing the transition described below. This included approximately 85 percent of Dukehart's time and that of the newly hired development director in the six months preceding the spin-off.

- Lastly, it's important that the organization have sufficient reserves to cover costs during the period of transition and prior to receiving the 501(c)(3) status necessary to raise funds independently.

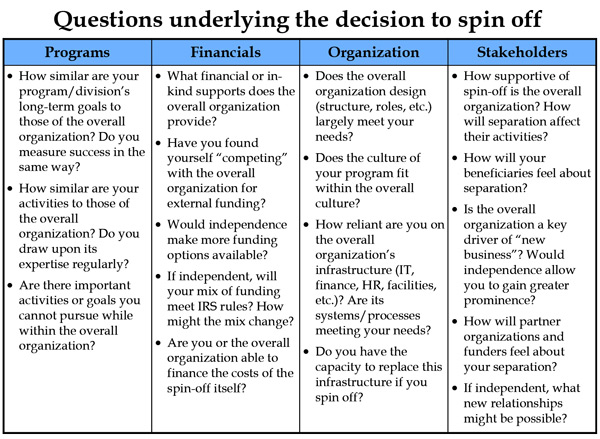

To be confident in the decision to spin off, leaders must fully consider the pros and cons of the existing relationship, determine if separation makes sense, and if so, what the best timing might be. Typically, this will require that the parent and program together engage a range of key stakeholders, including major partners, funders, and customers (See pull box on "Questions underlying the decision to spin off.")

Making the Decision

For Gateway the question of whether to spin off had first emerged three years earlier. In 2005 Gateway worked closely with the Bridgespan Group, a nonprofit consultancy, to develop a business plan outlining its goals and growth trajectory.

During the planning it became clear that while PCC's support would be an initial source of strength, the relationship might also conflict with Gateway's long-term goals. Each of the tensions described above—in structure, mission, and funding—could be anticipated.

Because of these early discussions, the PCC Board's vote to spin off the organization in October 2007 was not particularly controversial or unexpected. There was some consideration of creating a linked 501(c)(3), rather than a separate nonprofit. But PCC concluded—with the advice of legal counsel—that the diverging goals and activities required a clear separation.

For organizations housed within nonprofit incubators, the decision is likely to be similarly straightforward. In these cases the nature of the relationship has assumed that a spin-off would take place eventually, and the question is more about when, not whether, the separation should occur.

In more delicate situations—where spinning off may be the result of tough decisions on the part of one or both organizations—it's crucial to both honor the past relationship and recognize the new organization's independence. As we see below, the parent's continued engagement is necessary during the transition itself and can be quite helpful beyond.

Keeping the Big Picture in Mind

When an organization transitions to independent 501(c)(3) status, it has the opportunity to improve internal systems and external positioning. At the same time, key elements of its design and financial model may be shifting. Recognizing that, Gateway worked with Bridgespan to "refresh" its 2005 business plan in the months prior to spin-off. This process included reviewing Gateway's operating expenses as a standalone organization and researching the funding opportunities now available to it. As a second area of focus, Gateway considered its goals for its students and partners. Along with the financials, Gateway's desired impact would shape how it prioritized activities.

Not all programs undergoing this type of transition will need an extensive strategic assessment. But an organization that has a clear sense of its direction and the resources available to it will be better able to make key choices along the way.

What are the nuts and bolts of setting up your own nonprofit?

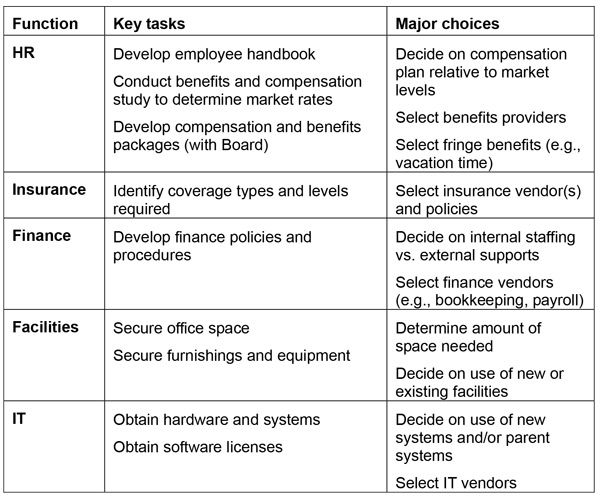

For a program that has been housed within a larger entity, the mechanics of becoming an independent organization can be the most intimidating (and certainly the most time-consuming) aspect of the transition. For Dukehart and her team, these mechanics fell into three buckets of work:

- Legally becoming a 501(c)(3): incorporating as a nonprofit and filing a 1023 with the IRS;

- Building a back office to replace and improve upon the operational infrastructure PCC had provided (human resources, finance, information technology, facilities); and

- Developing transfer agreements to codify the movement of people and intellectual property.

Becoming and Independent Organization in the Eyes of the Law

As noted above Dukehart and her team spent the equivalent of one full-time person-year managing the spin-off process. They concentrated their work in the six months prior to their launch as an independent entity. Within that period, they dedicated approximately five to six weeks to preparing the 1023 form.

The good news is the process of drafting the 1023 is an opportunity to reflect on how the organization has developed to date and how it should function in the future. For example, Part II: Organizational Structure requires the organization to identify the structure and roles of the Board, as well as any potential conflicts of interest.

But the benefits of this process do not change the fact that the 1023 is a time-consuming affair. The form has 11 sections and eight schedules (see pull box on "The 1023 form"). Applicants must complete each section and often one or more of the schedules, depending on the circumstances and type of organization. Several items, such as the articles of incorporation, must be completed in advance. Others, such as the narrative, may require the expertise of an attorney.

The 1023 form

- Part I: Identification of Applicant

- Part II: Organizational Structure*

- Part III: Required Provisions in Your Organizing Document

- Part IV: Narrative Description of Your Activities*

- Part V: Compensation and Other Financial Arrangements With Your Officers, Directors, Trustees, Employees, and Independent Contractors

- Part VI: Your Members and Other Individuals That Receive Benefits From You

- Part VII: Your History

- Part VIII: Your Specific Activities

- Part IX: Financial Data*

- Part X: Public Charity Status

- Part XI: User Fee Information

*areas discussed in greater detail here

Of all the sections, Parts II, IV, and IX will likely require the most time to prepare.

- Part II: To complete Part II, the organization needs to state whether or not it is a corporation. Most spin-offs follow this route, which requires them to complete and file articles of incorporation with state authorities before submitting the 1023. Though requirements vary by state, the application typically requires the name of incorporation, names, and contact information for those responsible for the articles, specific purposes for organization, number of directors, and bylaws.

- Part IV: Writing the narrative may have been the most time-intensive element of the 1023 for Gateway. This section asks the organization to describe its past, present and future activities. For each activity, the applicant must report who will be performing it, where it will take place, how it will be funded, and how much time will be required. Although the questions were relatively straightforward for Gateway, the team did have to clarify which past and current activities were performed by Gateway versus PCC. Because of the complexity of the situation and the law, Gateway needed legal advice to complete this portion of the form with confidence.

- Part IX: This financial portion of the 1023 requires a statement of revenues and expenses (budget), as well as a balance sheet. In Gateway's case the financials were not particularly time-consuming. Nevertheless, since many cost items were in flux (salaries, benefits, and rent), the team had to complete several drafts prior to submission. In addition, several tactical decisions required the advice of legal counsel, such as how to classify grants the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation had made to PCC, which then transferred to the new 501(c)(3). Gateway also sought legal counsel on whether or not to allocate certain funds as "unusual grants" because the decision would influence how future dollars would be categorized.

Building and Infrastructure

The challenge of building a new infrastructure will depend in part on: 1) the extent to which the parent organization manages current operations; and 2) the extent to which you plan to develop new systems versus continuing to rely on those already in use.

Vendor selection

For many portions of the organization’s infrastructure, Gateway contracted with external vendors or consultants. For example, a risks management broker helped select and purchase insurance policies, and various vendors will be providing web and IT services on an ongoing basis.

Rather than simply continuing to use PCC vendors, Gateway sought a minimum of three vendors for each product or service. The team then considered both cost and level of service to make a selection. When speaking to potential partners, they made it clear that they would need additional support during the initial months of the spin-off. This allowed them to select providers based on responsiveness as well as projected fee.

For most organizations, infrastructure decisions will vary by function. Gateway, for example, decided to sublease office space from PCC and was able to avoid the search for new space and moving costs. However, security and license issues prohibited Gateway from using PCC's IT network and software, and the team had to purchase and install new systems for future use. While it is natural to focus on the loss of supports, especially those previously taken for granted, this period also represents a unique opportunity to establish the processes that will best meet the organization's long-term needs.

HR systems and policies: Dukehart often had felt that PCC's salary structure and job descriptions did not align well with the needs of her employees. The spin-off was an opportunity to correct this mismatch.

- To determine appropriate salary and benefits schedules, Gateway commissioned a compensation study from Technical Assistance for Community Services (TACS), a local nonprofit consultancy. The study confirmed that, while Gateway's benefits were considerably better than comparable positions at other nonprofits, salaries were often below market rates. By understanding the landscape, Gateway was able to present the Board with suitable compensation packages for approval.

- In conversation with her team, Dukehart also developed new job descriptions (see Appendix for general classifications and a sample job description). Previous descriptions were written for staff operating within a community college system and did not truly represent the breadth of team member responsibilities. The new descriptions better captured the work being done and the career ladder within the organization (from program manager to program director, for example).

In the final month prior to spin-off, Dukehart offered staff their "new" positions, including their updated salaries and benefits.

Next on the HR agenda was a new employee handbook. Handbooks generally outline compensation, benefits, vacation and sick-time policies, equal opportunity and sexual harassment procedures, performance evaluation protocols, and other areas essential to employee relations. Since policies can potentially expose or protect the organization from legal liability, developing a handbook requires expert help. Gateway used a first draft from TACS as a starting point, modified it to fit the organization's needs, incorporated input from an employment lawyer, and had the Board approve the final draft. (See Appendix for a listing of contents in Gateway's employee handbook.)

Insurance: Programs covered under a parent's umbrella policies likely will spend significant time untangling the types and levels of coverage necessary to adequately manage their risk as an independent entity. Often they will need general liability, directors and officers, bonding, professional liability and non-owned vehicle liability policies. Gateway found that nonprofits working with children, youth, or other vulnerable populations often have greater costs and/or coverage requirements than other, similarly sized organizations.

Finance: To establish its own finance system Gateway had to select basic financial software and develop payroll, banking and investment policies. Ideally the organization would have had a Finance Director in place to lead that process. Lacking that, Gateway contracted with a financial services consulting firm to develop a chart of accounts, prepare an RFP for banking services, coordinate the bidding for accounting software, and assist with early-stage interviews of finance director candidates. By outsourcing these tasks Dukehart was able to allocate scarce internal resources to other aspects of the spin-off process.

Facilities: During a spin-off one of the biggest questions an organization must answer is where it will reside. While Gateway did consider outside office space, it ultimately decided that being on the campus of a functioning site and maintaining relationships with PCC outweighed any advantages of a new space, such as more offices and greater control over layout.

IT: The fact that Gateway was no longer part of PCC meant that all IT systems, hardware, and software had to be separated. Gateway could no longer take advantage of the college's Internet, e-mail, servers, and software licenses. This was a significant investment. To contain its expenses the team managed to delay some purchases until after Gateway's official spin-off, when it could take advantage of available nonprofit discounts for software and operating systems.

Transfer Agreements

While many nonprofits will not have extensive contracts, most existing agreements will have to be transferred from the parent organization to the new entity. In addition, assets, such as computers, office equipment, or intellectual property, may have to be transferred as well.

In the case at hand, three types of agreements or assets had to be transferred to Gateway:

- Contracts between its partner colleges (the sites replicating the Gateway program) and PCC;

- Agreements between Gateway's funders and PCC; and

- Assets, such as money, computers, and any equipment purchased with Gateway funding. This also included the transfer of personnel from PCC to Gateway, as well as agreements regarding benefits and collective bargaining requirements.

Gateway and PCC also negotiated ownership and usage of intellectual property developed both before and after the spin-off (naming, logos, curriculum, etc.).

A few key learnings: Although Gateway began developing transfer agreements early on, the large number of people and departments involved often slowed down the process. Having a champion to push these agreements through was essential. Dr. Nan Poppe, PCC Campus President and Chair of the new Gateway Board, played that role, advocating to have negotiations and approvals completed in a timely manner. Finally, as with many aspects of the spin-off, Gateway's and PCC's legal counsel needed to be involved in preparing the transfer agreements.

Additional considerations when separating from a large public institution

- Timing: Large, public institutions often have several layers of bureaucracy or various departments to navigate. Give yourself enough time—more than you might expect—to engage the necessary parties, make decisions, and complete paperwork.

- Negotiations: Conflict of interest regulations dictate that public institutions negotiate agreements "at arm's length" and avoid treating one organization better than others (e.g., agreeing to more favorable leasing terms). In some cases this will mean less favorable terms than one had as an internal program.

- Union requirements: Many public employees are unionized. The new organization must be aware of how items like vacation and sick time will transfer to the new nonprofit. Make sure both the parent and the spinning-off organization follow the stipulations of collective bargaining agreements, such as giving adequate notice before terminating an employee (even if the employee is to be rehired by the new organization).

- Other statutory regulations: In addition to noting the difference in Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) between nonprofits and public entities, it is important to identify any state or local statutes that might govern the transfer of public employees, property, etc.

In light of these considerations, Gateway selected TACS, a consultancy with significant experience working with public institutions, to support the spin-off process.

How will the organization need to evolve?

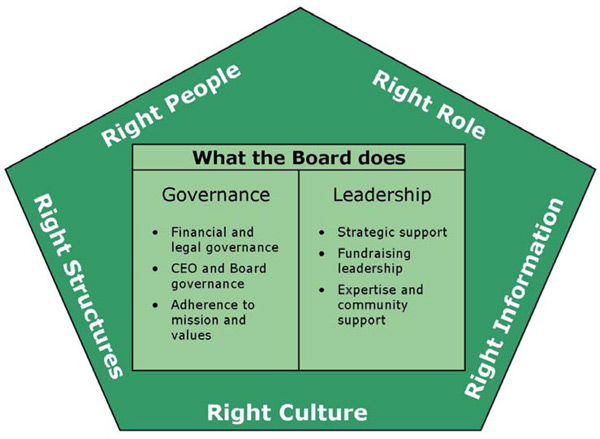

Building and Developing a Board

One of the most important elements of any new organization, particularly a 501(c)(3), is its Board. The Board is legally responsible for setting the direction of the organization, overseeing finances, and selecting the ED. In many cases Board members also play crucial roles in fundraising and advocacy.

The capabilities a nonprofit seeks in its Board will depend in part on the organization's goals. For example, an organization that anticipates launching significant public relations and communications campaigns may want to have that expertise represented on the Board. Ideally, the group will include a mix of backgrounds, talents, and points of view, as well as personalities that can work productively together.

Gateway built a Board that represented stakeholder interests and included leaders within the field of alternative education. One third of the members were nominated by PCC, as was determined at the time of the spin-off decision. This allowed the college to maintain an ongoing interest in the organization. An additional third were site representatives, and a final third were “at-large” positions nominated by Dukehart and her team. All had been engaged, either professionally or through volunteer work, with postsecondary education and were passionate about the high school dropout challenge. Additionally, each member had extensive leadership experience within the nonprofit or public sector.

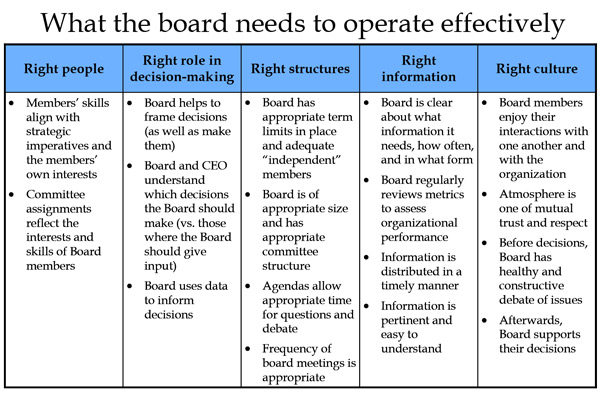

Of course, selection is only a first step in the process of launching a high-performing Board. A strong Board—one that is an asset for the organization—requires effective management by the Board chair and in partnership with the ED.

(See pull box on “What a Board needs to be Effective” and Appendix for additional resources on nonprofit Boards.)

Getting off to the right start will require:

- Ensuring the Board understands its legal and fiduciary responsibilities;

- Educating members about the strategy and basic operations of the organization;

- Clarifying how the Board will function vis-à-vis the ED, staff, and other decision-makers; and

- Making space for Board members to get to know one another and the organization's leadership team.

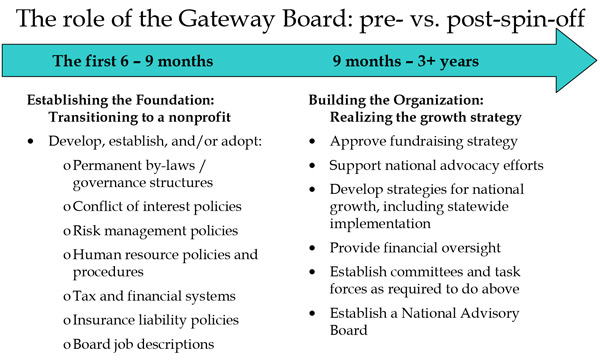

For the first six months Gateway's Board focused primarily on the tactical decisions required to transition to 501(c)(3) status, conducting several meetings in person and by phone. When those tasks were complete, the Board began to engage on broader strategic concerns. (See pull box on “The Role of the Gateway Board: pre- vs. post-spin-off.)

To facilitate this shift, the group held a day-long retreat in the month following the spin -off. While Board members were well aware of their legal responsibilities (they were asked to review them before agreeing to serve), key agenda items included a mix of informing, sharing experiences, and clarifying roles.

Filling Capability Gaps

Most organizations will not be able leave their parent behind and take advantage of new opportunities without adding new capabilities to their staffing mix. For Gateway two new functional roles were essential: a director of development and a finance director.

- Anticipating a need for greater, more diverse fundraising, Dukehart recruited David Johnson, a member of PCC's grants office, to join the staff as the director of development.

- After the spin-off, Gateway could no longer rely on PCC to administer payroll, accounts payable, etc. With support from a financial services consulting firm, Dukehart launched a search to fill a new financial director position. Knowing it might take time to find the right mix of capabilities and commitment to Gateway's mission, she also asked the firm to provide interim support (e.g., designing a chart of accounts, overseeing software installation, and ensuring compatibility with electronic banking systems).

As spin-off organizations seek to fill gaps, they should consider opportunities to maximize in-house talent—as well as capabilities that may be better filled externally. In cases where skills are highly specialized or intermittently required, it may make sense to outsource or contract (e.g., IT supports for an organization with minimal reliance on technology).

Clarifying Decision Roles

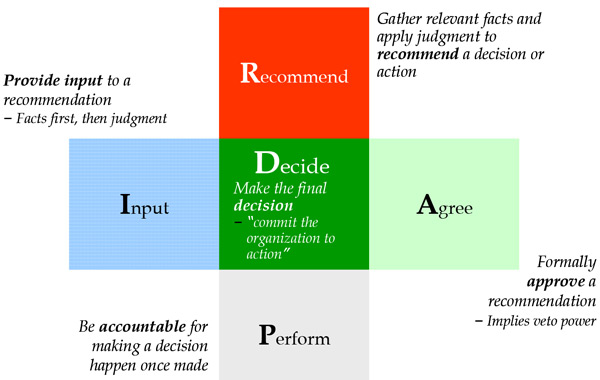

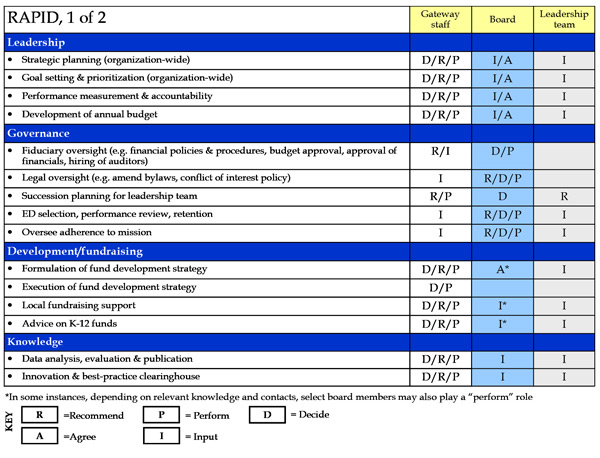

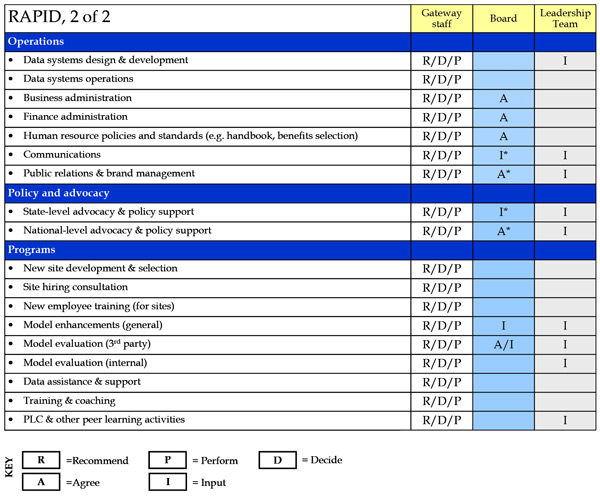

All organizations can benefit from a periodic review of decision roles, particularly when launching or completing a transition. For Gateway, the spin-off entailed both a shift in activities and the addition of new stakeholders. With that in mind, Dukehart and her team worked with Bridgespan to conduct a “RAPID assessment” of their major functions.

RAPIDSM is a framework that helps untangle decision-making processes by identifying all of the activities that must occur for a decision to be made well. The name is an acronym for decision-making activities. At the outset, for example, someone must recommend that a decision be made. Input likely will be required to inform the decision. Often, more than one person must approve or agree with the final call, but ultimately someone must have the authority to decide. Then, after a decision is made, it must be carried out, or performed.

RAPID encourages people to be more thoughtful about how decisions are made. The tool helps give real accountability to the right people, allowing power to be shared but also setting useful boundaries. By involving the right people and minimizing others' involvement, RAPID saves time.

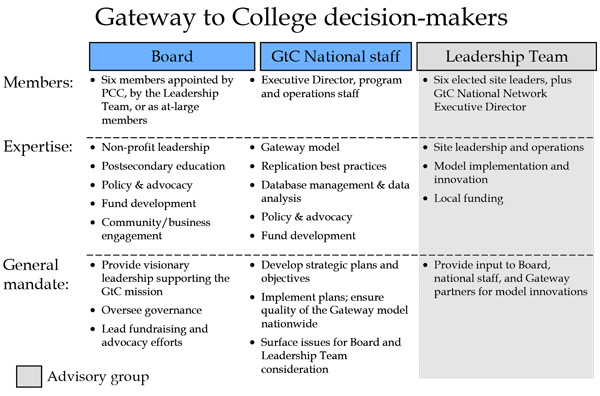

In Gateway's case, there were three major groups involved in decision-making: the Gateway staff (including the ED), the new Board, and an advisory committee of site representatives (the Leadership Team). With Bridgespan's support, Dukehart and her team identified key areas of shared decision-making and assigned roles. This was then vetted with the Board to ensure it aligned with its expectations.

With regard to strategic planning, for example, the group determined that National Network staff would be responsible for recommending, deciding upon, and performing the plan. However, the staff needed to solicit nput from the Board and Leadership Team. And the Board had to approve (or veto) the final decision.

The Appendix includes a full copy of Gateway's initial RAPID assessment. Note that all RAPIDs should be considered living documents. If an organization changes its design, programs, or strategy, it may need to revisit its decision processes. (RAPID was originally developed by Bain & Company as part of its decision-driven organization work. For additional discussion, read "RAPID Decision-making".)

The importance of clarifying roles—particularly between the Board and staff—cannot be overestimated. Many spin-offs will have had limited contact with the Boards of their parent organizations. Having a new, engaged set of voices in discussions—voices with ultimate responsibility for the nonprofit's success—can be disconcerting. Setting expectations will ease the transition for staff and pave the way for a more effective and productive Board.

Executive Director: Stop, Start, Continue

Going through the RAPID process prompted Dukehart to reflect on how her own activities would change after the spin-off. Dukehart had served as Gateway's replication manager since 2003. In this role she codified the Gateway model, created training protocols and materials, selected sites, and assisted in site start-up. While these activities would remain central to Gateway's work, Dukehart's position as ED would call for a somewhat different set of priorities. To help her think through that shift, Dukehart constructed a “STOP, START, CONTINUE” list highlighting major points of change and continuity.

Stop:

- Transitioning to 501(c)(3) status: Now that the spin-off preparation was behind her, Dukehart would regain a large chunk of time to devote to other activities.

- Navigating PCC rules and regulations: With independent systems in place, Dukehart and her team could spend less time on administrative compliance.

- Managing day-to-day financials: Adding a talented chief financial officer (CFO) would give Dukehart significant support on the planning and execution of financial tasks, particularly once the CFO's training and integration was complete.

- Working on programs, as much as possible: In the years preceding the spin-off, Dukehart had developed her program bench strength, so she could distribute management across her team. For example, she had trained one member of the program team to field site inquiries and manage new site selection. Another led training and development for existing sites. This kind of delegation would need to continue and cascade to new hires as the number of sites and national staff grew.

Start:

- Developing Board: Dukehart would need to work closely with the Board chair and officers to ensure effective governance, strategy development, and operations. Specifically, she would manage a timely flow of information to the Board, plan meetings in partnership with the Board chair, and see that decisions were communicated efficiently to staff.

- Expanding fundraising: While Dukehart had always served as the face of the organization to funders, she and the new director of development anticipated expanded outreach for the newly independent organization. Dukehart would supervise and participate in these activities.

- Developing and managing new nonprofit operations: While the spin-off itself was complete, the first year of operations in particular would involve ongoing decision points and codification of standard practices.

Continue:

- Maintaining a collaborative, reflective culture: Gateway's culture is a point of pride for Dukehart and her team. The team of nine emphasizes customer service—always trying to do better for its students and site partners—and a culture that respects each member's contributions and point of view. While the exact shape of things would change with growth, Dukehart was committed to maintaining the spirit of the pre-spin-off organization.

Of course, the spin-off process itself accelerated changes in Dukehart's role. In order to execute the nuts and bolts described above and to launch a new Board, she had to delegate elements of day-to-day program management and operations.

Concluding thought: execution is key

Knowing what to do and being able to do it are two different things. Several factors helped Gateway successfully navigate a challenging and potentially difficult transition:

- Dukehart provided clear direction and commitment throughout. She realized early on how challenging and time-consuming the spin-off process would be, as well as how important independence would be for Gateway's long-term goals. She dedicated resources (in particular, her own time and David Johnson's) toward the effort, even though it required being less involved in ongoing operations.

- As Dukehart shifted her attention, strong leaders within the organization kept programs and services on track. The collaborative, entrepreneurial spirit of the Gateway team and the efficiency of the replication process allowed the organization to maintain and grow day-to-day operations throughout the process. The fact that the staff embraced the shift, rather than fearing the change, was critical.

- Lastly, Gateway's major stakeholder groups supported the transition. The PCC Board had nominated Dr. Nan Poppe, PCC campus president, to lead Gateway's new Board. She was a champion throughout, often helping to push decisions and paperwork ahead when it might otherwise have stalled. Similarly, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation—a chief funder and long-time supporter of Gateway's model—encouraged the shift and the thoughtful planning required for a successful transition.

Appendix

List of Resources by Topic

Leadership

Board

Decision-making

Human resources

Operations

Gateway to College Job Classification*

Executive Director

Program Director

Program Manager

Program Assistant

Coaches

* Based on an education consulting model similar to that used by other non-profit organizations

Gateway to College Sample Job Description

Role: Director of New Program Development

Duties

Accountabilities

Supervision & Reporting

Requirements

GATEWAY TO COLLEGE EMPLOYEE HANDBOOK, TABLE OF CONTENTS

- List of Resources

- Gateway to College Job Classification

- Gateway to College Sample Job Description

- Gateway to College Employee Handbook, Table of Contents

- Overview of Gateway Decision-Makers

- Gateway to College RAPID Framework

- Spin-Off Workplan: Key Tasks & Timing

- Good to Great in the Social Sectors, Jim Collins

- The Simple Difficulty of Being a CEO, Patrick Lencioni

- Managing the Dynamics of Change, Oliver Wyman—Delta Organization & Leadership

- New Work of the Nonprofit Board, Barbara E. Taylor, Richard P. Chait, and Thomas P. Holland

- Governance as Leadership, Richard P. Chait, William P. Ryan, and Barbara E. Taylor

- The Source: Twelve Principles that Power Exceptional Boards, BoardSource

- www.boardsource.net

- RAPIDSM Decision-making, Jon Huggett & Caitrin Moran

- www.npgoodpractice.org, see Nonprofit Good Practice Guide: Organizational Management (HR)

- www.idealist.org, see Introduction to Nonprofit HR

- www.bridgestar.org

- Full-time, exempt, with benefits. Master's degree or higher required.

- Reports to the Board of Directors; responsible for overall operation of the nonprofit organization.

- Full-time, exempt, with benefits. Master's degree or higher preferred. Professional licensure or significant relevant experience may substitute for master's degree; however, a bachelor's degree is required with professional equivalency.

- Leadership position within the organization requiring a high level of specialized knowledge. Represents the organization nationally. Requires discretion and good judgment to sustain funding and program services, and avoid liability or negative publicity for the organization. May supervise others. Examples: Finance Director, Director of New Program Development

- Full- or part-time, exempt, with benefits at 24 regularly scheduled hours per week (prorated for part-time employees). Bachelor's degree required. Master's degree or higher preferred.

- Responsible for operations in a key area such as communications or site support. Represents the organization nationally. May supervise others. Examples: Communications Manager, Research Manager

- Full- or part-time, non-exempt, with benefits at 24 regularly scheduled hours per week (prorated for part-time employees). Associate's degree or higher required.

- Supports the organization with clerical skills and event logistics planning. Example: Administrative Assistant.

- Experienced educators, not necessarily located in Portland, supporting network partner sites through training and on-site support, such as classroom teaching reviews and curriculum improvement. Reports to Program Director.

- Coaches will usually be independent contractors. Coaches may also be hired as part-time or full-time employees, under the classification of Program Manager.

- Develops strategies for new program development

- Oversees site selection for new sites

- Represents the organization nationally

- Analyzes funder requirements to ensure site selection targets meet funder parameters

- Negotiates program service contracts and assures program quality and contract compliance with senior-level education professionals

- Conducts policy and funding analysis

- Coordinates work with the Early College High School Initiative, Alternative High School Initiative, and similar groups

- Organizes visits for potential partners

- Other duties as assigned

- Meet growth expectations set by the board of directors

- Timely delivery of all program elements

- Excellent relationships with senior-level education professionals

- Site selection promotes service to the National Network target population

- No supervisory responsibility

- Reports to Executive Director

- Works cooperatively with Director of Development on expansion priorities

- Works cooperatively with Communications Manager on policy efforts

- Works cooperatively with Finance Director to develop contracts

- Works cooperatively with Program Specialist on site visit events

- Master's degree in public policy, public administration, education or similar field

- Demonstrated experience managing complex, long-term, multi-layered projects

- Demonstrated experience designing and conducting trainings for diverse audience with varied levels of experience and skill sets

- Requires a high level of creative diplomacy

- Ability and willingness to travel nationally

- Ability to work collaboratively in a fast-paced and diverse team environment

- I. Introduction

- Gateway to College National Network's Mission

- General Employment Policy

- Employment-at-Will

- Equal Employment Opportunity

- Prevention of Harassment &Discrimination

- Disability Accommodation Policy

- Drug-Free Workplace Policy

- Personnel Files

- Response to Reference Check Inquiries

- Personnel Data Changes

- Categories of Employment

- Employment Evaluations

- Payment Periods

- Direct Deposit

- Holidays

- Vacation Leave

- Sick Leave

- Personnel Days

- Office Closure

- Bereavement Leave

- Domestic Violence Leave (Leave to Address Specific Crimes)

- Leave for Personal Reasons

- Medical Insurance

- Long-Term Disability Insurance

- Flexible Spending Account

- Retirement

- Required Benefits

- Conflict of Interest

- Standards of Conduct and Discipline

- Internet, E-mail, and Electronic Systems Usage Policy

- Contact with Media

- Youth Protection

- Automobile

- Workplace Safety

- Work Schedules

- Normal Office Hours

- Travel for Non-Exempt and Casual Employees

OVERVIEW OF GATEWAY DECISION-MAKERS

GATEWAY TO COLLEGE RAPID FRAMEWORK

SPIN-OFF WORKPLAN: KEY TASKS & TIMING

Note: * This case study is not designed to provide legal advice regarding the spin-off process. Organizations considering a separation from their parent organizations should seek appropriate legal counsel.