Authors' Note

Are you sure that replicating is right for your organization? And if so, are you ready?

This article is intended for nonprofit leaders who have already determined that replication is the right way to grow their organizations. But reaching that point can itself be tremendously difficult. If you are not sure whether replication is the right strategy for your organization, or if you have made that decision, but you’re not sure that your organization is ready to replicate, we encourage you to ask yourself the following questions:

- Do we have evidence that our program produces positive results?

- Do we know which elements of our program are required to be effective?

- Are our current organization and finances strong?

Affirmative answers to all three questions are a baseline requirement of readiness for replication. For further information, we encourage you to read “Going to Scale: The Challenge of Replicating Social Programs,” by Jeff Bradach, which was published in the Spring 2003 issue of the Stanford Social Innovation Review, and “Scaling Social Impact: Strategies for Spreading Social Innovation,” by Gregory Dees, Beth Battle Anderson and Jane Wei-Skillern, which was published in the Spring 2004 issue of the Stanford Social Innovation Review. These articles explore different ways to grow a nonprofit organization and provide a foundation for nonprofits considering growth through replication.

You've made the pivotal decision to expand and replicate your program in one or more new locations. This means you have a model that works, and you know which of its elements are essential. But as you probably suspect, the hardest work is yet to come. Keeping a home site running smoothly while simultaneously making a rapid-fire array of decisions that affect a new site is a daunting task. It is particularly challenging when your long-term plans include multiple sites and you know that the choices you make today will heavily influence the impact your organization will be able to have down the road.

Is there a way to make this process easier to navigate? To answer that question, we surveyed a group of nonprofit leaders who have successfully grown their organizations through replication.[1] Their responses, coupled with Bridgespan’s experience with nonprofits that operate in multiple locations, suggest that a few key decisions play a critical role in the success of new sites. Ironically, some of these may not even look like decisions to the senior managers of an organization that is poised to replicate. But with the benefit of hindsight, they quickly come into focus as the ones that matter the most.

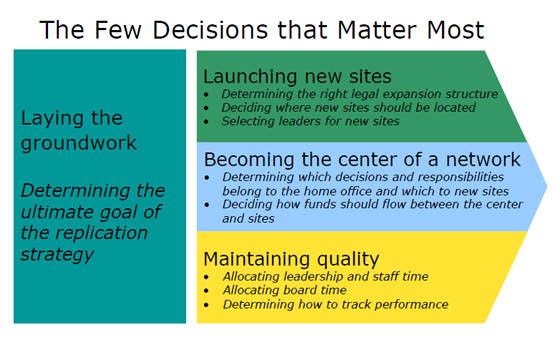

The accompanying chart summarizes these critical decisions. While we’ve grouped them in the order in which they tend to surface, in reality, there is often substantial overlap and iteration. So don’t be surprised if you find yourself facing several at the same time.

The rest of this article will explore these decisions in detail. What follows is not a comprehensive “cookbook,” however, but a guidebook, informed by others’ experiences, for how to plan your journey and take your first steps.

Laying the Groundwork

What is the ultimate goal of your replication strategy? Many leadership teams, having decided that replication is the right course of action, believe this question has already been answered. But deciding that your nonprofit should replicate is not the same as deciding to what end it should replicate. Beyond a common desire to increase impact, Board and staff members often harbor different motivations for opening new sites, and different expectations about what, exactly, “success” will mean.

It’s important to surface and resolve these differences collaboratively, even if it seems to the group as a whole that there is agreement at a high level. Getting aligned early on is useful groundwork; it will make more tactical and tangible decisions easier by helping you consider the pros and cons of each against a single objective. Deciding that your primary goal is serving more youth, for example, will lead to a different set of choices than deciding that success means influencing state policy, or convincing others to adopt your model. One definition of success might lead you to open locations close to your home site; another might lead you to target urban locations across the country for replication; a third might lead you to seek out a diverse mix of sites.

Two youth-serving nonprofits, Higher Achievement and Aspire Public Schools, offer examples of the benefits of alignment:

Higher Achievement, based in Washington, D.C., offers after-school and summer academic programs for middle school students in low-income areas. Early on, the organization opened a satellite site, in nearby Alexandria. But as Higher Achievement served increasing numbers of children successfully in these two locations, its leaders began thinking about the possibility of serving more students through program replication. Several communities had reached out to them; they also pro-actively scoped a few possible new locations. Soon, they found themselves with a number of potential sites to choose from, located as near as Baltimore and as far away as the San Francisco Bay area. Several of the sites were relatively equal in terms of their need for the program, and their potential to attract funding and local leadership. But with a unified perspective on a very straightforward goal—serving more youth and closing the achievement gap—the team realized that operational ease could be a critical differentiator. As a result, they opted for Baltimore, where existing staff could most easily spend time in the new community, build relationships, and support the start-up effort.

Leaders at San Francisco-based Aspire Public Schools, in contrast, determined that their definition of success was improving public education outcomes throughout the state of California. To achieve these goals, they would need to open Aspire schools in highly visible districts across the state where the need was greatest so that they could increase the numbers of students they were serving and, at the same time, increase the organization’s ability to influence policy-makers. Before articulating this goal, Aspire had created new schools based on the availability of facilities and opportunities provided by supportive districts. With a unified purpose, however, team members were able to identify three specific geographies (the Bay Area, the Central Valley, and Los Angeles) in which they felt Aspire needed to operate. They subsequently developed an explicit growth strategy around those three regions.

Launching New Sites

Once your leadership team is clear on the definition of success, you can turn your attention to the task of launching your new site(s). Three decisions emerge as most important in this phase of replication: Determining the right legal structure; deciding where new sites should be located; and selecting the leader(s).

Determining the Right Legal Expansion Structure

Legal structure—the decision to launch new sites under a single legal entity, through multiple independent legal entities, or as programs licensed to third-party organizations—affects issues ranging from quality control to fundraising, growth rate, costs, and ease of management. This decision also comes with a host of conventional wisdom. It is commonly believed, for example, that you should remain a single 501(c)(3) if you want to ensure better quality control and ease of management. Conversely, if you want to tap into local ownership and funding potential, conventional wisdom indicates that you should grow using a multiple 501(c)(3) structure. If you’re most concerned with growing quickly and less expensively, conventional wisdom holds that having third-party organizations replicate your program is the way to go.

There is some truth in each of these beliefs, and yet the reality is more nuanced. Making the right decision is more dependent on case-by-case factors than conventional wisdom would lead you to believe. Your best bet, therefore, may be to start with a clear sense of your priorities. Look at what the conventional wisdom has to say. But then test whether you’ve actually been pointed in the right direction. No single structure will be optimal for every aspect of a given organization’s business, and although each has benefits, each also has risks that may not be apparent at first glance.

Let’s walk through several examples—some organizations that successfully realized the benefits and mitigated the risks of their chosen legal structure, and others that took conventional wisdom at face value and subsequently fell short of their aspirations for replication.

Legal structure and fundraising at local levels

Consider the conventional wisdom suggesting that a single 501(c)(3) structure allows an organization to retain high levels of central control, but makes it more difficult to fundraise successfully at local levels. Summer Search, a leadership development program for low-income youth, replicated its program from one site in San Francisco to seven sites across the country while remaining under a single 501(c)(3). However, its leadership was determined to find a way to tap in to local donors and did not let its legal structure stand in their way. Even though the local sites were not independent legal entities and therefore did not have their own legal boards, local advisory boards were established and were asked explicitly to raise funds. According to CEO Jay Jacobs, these boards continue to play a key role in individual fundraising, which in aggregate accounts for nearly half of organization-wide revenue.[2]

By contrast, conventional wisdom suggests that organizing as multiple legal entities stimulates local fundraising. Yet when the leaders of another nonprofit thought that structure alone was enough to make those reputed benefits a reality, they ended up frustrated. This particular multi-service youth-oriented organization now operates in nearly 20 sites around the country. While the sites were originally all part of the same legal entity, several years ago the organization made the switch to multiple legal entities in order to try to reduce site dependence on central office subsidies and stimulate local fundraising. However, following this switch, the expected gains did not materialize. Looking back, this organization’s leaders attribute the fundraising problems to their own failure to give newly-formed local boards a clear mandate to fundraise for the costs of their own local organizations. Today, this nonprofit’s central office still subsidizes approximately 30 to 40 percent of the costs of its other locations—a rate not dissimilar to that prior to the legal decentralization of the network.

Independent of legal structure, what’s actually most important for local fundraising success is setting appropriate expectations, providing the right amount of support, and holding local entities accountable for covering their own costs. A given legal structure is neither a guarantee of success nor an insurmountable barrier.

Legal structure and growth rate

What about the conventional wisdom surrounding growth rate? Again, each case is unique. Consider one specialized youth development nonprofit whose leaders initially chose to replicate by licensing its program to third-party organizations as a strategy for rapid growth. While initial results were positive in terms of opening new sites, they discovered over time that on average, growing the program through other organizations resulted in sites that served fewer youth, with twice the turnover of sites run by the central organization. Because much of the cost was in launching a new site, the fact that many of these sites shut down after a couple of years meant that this path actually proved to be twice as expensive as the alternative of expanding through the existing organization.

This reality was a tough discovery for the organization. While the potential for rapid growth had been alluring, the mechanics of working with other organizations meant that there were also a number of risks: The program was being delivered outside the direct legal control of the home office. Presumably it was only one of a number of programs being offered by an umbrella organization that had its own mission and priorities. It could be discontinued at any time the umbrella organization chose. In this case, these risks proved to be too substantial to manage, and therefore outweighed the purported benefits.

By contrast, replicating through other organizations has worked well for Nurse-Family Partnership (NFP), an evidence-based home-visitation program for vulnerable first-time mothers and their infant children. After 20 years of refining its program through research and randomized control trials in multiple geographic and demographic environments, the organization replicated a handful of programs throughout the United States, successfully expanding to over 300 counties in the last 12 years.[3] In large part, NFP has succeeded in mitigating the risks and realizing the benefits of replicating through other organizations. Several factors have contributed to the organization’s success, among them:

- An evidence-based and rigorously tested model has given NFP the credibility to say that the program has to be implemented in a very specific way;

- A diverse, sustainable economic model, driven by government funding at the local level and foundation funding for the national office, has provided funding stability for both parts of the organization;[4]

- Alignment with host organizations’ central missions has helped NFP mitigate the risk of site turnover;

- Core services provided by NFP (e.g. program and clinical consultation with local staff) have proven NFP’s value to sites and built incentives for sites to maintain good relations;

- Robust systems to track data have enabled NFP to hold sites accountable and serve as an early warning system.

This list reflects the elements of NFP’s model that make it conducive to replicating through other organizations, as well as a very deliberate set of investments that NFP has made that allow it to manage the risks associated with this strategy so that it reaps the benefits while avoiding the pitfalls.

As Summer Search and NFP demonstrate, conventional wisdom can provide a solid platform for growth if you take the time to figure out how to make sure your organization can realize the benefits it promises, and then aggressively work to manage its inherent risks.

Legal Structure Aside, How Fast Should You Grow?

Many nonprofit leaders worry about the frequency and speed at which they should roll out new sites. However, attempts to plan this at the very beginning tend to meet with mixed success: Reflecting upon their initial expectations, about 30 percent of organizations report having overestimated their growth, 20 percent report having underestimated, and half report having estimated about the correct rate..

Planning for future growth is important, but the less experience the organization has with expansion, the more difficult it is to predict accurately. Therefore, spending significant time on making a specific prediction before having replicated a few times may be a distraction from the most important objective: getting your first couple sites up and running. Later, when you do make a more robust projection of long-term growth rates, make sure to consider the financial and human resources that will be necessary to support that growth.

Deciding Where New Sites Should Be Located

As organizations first consider where to grow, two mistakes are common: trying to choose new sites proactively purely on the basis of analysis, and responding too eagerly to others’ requests. In the first case, local stakeholder enthusiasm often proves hard to come by or the nonprofit’s leaders end up compromising their program in order to convince a new geography to take it on. In the second, they often end up jumping in before ensuring that the new location is actually a good ‘fit’ for the organization’s expansion plans.

The best route, we find, is to take elements of both approaches, namely site assessment and responsiveness to outside interest, and to apply them in a measured and balanced way. Essentially, we encourage you to be strategically opportunistic—poised to take advantage of opportunities as they come, but being discerning about which you take and which you let pass by.

Early in an organization’s replication efforts, it will probably need to be mostly responsive to outside interest, so it’s rarely worth the effort to go through an extensive analysis process to “pick” new geographies. (We know of one group of leaders, for example, who invested a great deal of time investigating and analyzing more than 20 possible target locations, only to end up replicating in communities that were nearby and expressed interest.) Later on, as replication efforts pick up steam, the organization’s brand may become stronger, in which case a proactive approach of identifying desirable cities to enter becomes more feasible.

In the world of replication, the most practical way to be strategically opportunistic is to have an effective screening process for all potential sites. This requires being clear about your:

- Criteria for screening opportunities – such as demographics and community characteristics

- Non-negotiables – the elements that have to be in place, versus those where you can be flexible

Being clear up-front about such demographic and community criteria can potentially save a great deal of wasted effort exploring impossibilities. But at the same time, being too rigid about acceptable boundaries for these attributes—possibly by trying to match too closely the conditions that exist at your original site —can cause you to exclude some locations that might be potential winners. With experience, your understanding of what’s absolutely necessary to seed success in a new site will evolve, so it will be important to revisit and refine your criteria over time.

The experiences of Higher Achievement and MY TURN illustrate different approaches to honing a screening process. Higher Achievement started out with a fairly rigid set of criteria including a specific school structure and transportation for the participants taken care of by the school system, which allow its program to work effectively. However, when one replication opportunity presented highly promising prospects on all of the other important fronts except these two, the organization reconsidered and determined that in this case, it would be a good idea to work around those issues and experiment with new local conditions.

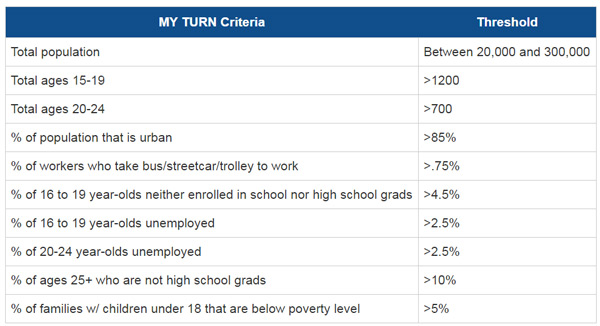

MY TURN, a leading provider of employment and educational services for youth in New England, created a thorough screening process when it was much further down the replication path. In 2004, after having grown to nine communities over 19 years, MY TURN identified 10 threshold criteria for which data were readily available to use in evaluating potential new sites. By looking at its current successful sites, it was able to set acceptable ranges for each criterion, and determined that sites had to pass all 10 criteria to be considered (see below). Not all organizations will have this number of criteria or level of specificity, but our experience is that having the data and the rationale to make good decisions can help organizations know when to say yes — and when to say no. MY TURN now uses this screening approach proactively with all new possible sites.

MY TURN Screening Criteria

Once a site has passed muster in terms of demographic and community criteria, it is time to think about your non-negotiables. What elements are so crucial that you believe your program will fail without them? What qualities or characteristics of a potential location will convince you that replicating there will contribute significantly to your organization’s long-term growth goals? These non-negotiables are often more difficult to assess than the community and demographic information. The next step, therefore, will require due diligence with potential new sites.

For example, Higher Achievement’s leaders have found that it is essential to build relationships and negotiate commitments across numerous local constituencies. As a result, their non-negotiables include: 1) school district superintendents committed to partnering with Higher Achievement to close the achievement gap; 2) heads of local foundations to open doors and commit to future funding; 3) grassroots support in the form of neighborhood leaders to lend credibility and convince parents to let their children participate in the program; and 4) local universities to access students to serve as volunteer mentors and teachers. Without those local relationships and partnerships in place, Higher Achievement does not move forward with opening a new site.

Selecting Leaders for New Sites

It would be difficult to overstate the importance of having strong leadership at new sites. The ideal candidate has relevant general skills and knowledge, clear alignment with the organization’s philosophy and values, local knowledge and connections, and specific expertise in the organization’s program. The first two qualities are non-negotiable. But often, you’ll have to choose between the latter two. Finding a candidate who has both local knowledge and specific program expertise is rare.

When forced to choose, two-thirds of the nonprofit leaders we spoke with indicated that local expertise proves more important. This makes sense when you consider that the success of a new site depends on its leader’s ability to form relationships, build an advisory board and make connections—not just manage the program.

MY TURN, for example, prioritizes local experience with other youth development entities in selecting new regional directors, having found that individuals with pre-existing relationships in the community were generally far more successful in launching regional advisory boards and raising local funds than staff members from other locations.

New leaders can certainly learn program specifics; so long as they believe in the program model, the issue is how fast they’re able to ascend the learning curve. One option is having a staff member from the home office transfer to the new location to compensate for the new leader’s initial inexperience. About half of the organizations we surveyed report that they transfer at least one experienced staff member from an existing office if the new ED does not come from within the organization. Another option we have seen is for the new leader to spend a “rotation” period at the home site, a method utilized by Manchester Bidwell Corporation, a Pittsburgh-based youth services and workforce development provider, and by the Omaha, Nebraska-based Boys Town, which provides a continuum of youth and family services to children in multiple locations across the country. Finally, the NYC-based Children’s Aid Society’s Carrera Adolescent Pregnancy Prevention Program brings programmatic expertise to all sites through a robust regional support system and centralized training for all new staff.

In the instances where we’ve seen organizations place more emphasis on organizational program expertise than local connections, there is often a pre-existing dedicated funding stream, typically governmental. For these organizations, the funding equation is usually largely solved through an up-front contract, so there is less of a need to do the sort of local fundraising that depends heavily on local connections and staff from an existing site can be utilized to bring the program to a new location. Youth Villages, a multi-service nonprofit serving troubled youth in nine states and the District of Columbia, ranging from Tennessee to North Carolina to Massachusetts, commonly uses such “transplant teams” to expand to new sites. In fact, Youth Villages will only open a new site if it can send a leader with experience at an existing Youth Villages site.

New locations have the best chance of survival and success when their leadership teams are not only aligned with the organization’s values but also represent a complete portfolio of local knowledge and programmatic skills. While the specific skills required may differ for different organizations, a thoughtful approach to identifying them is essential to selecting robust and effective new site leadership.

Becoming the Center of the Network

When an organization launches one or two new sites, its leaders tend not to be thinking about their “home office” becoming the “center” of a “network,” but that is what’s happening. Whatever foundation is built for those first couple sites will shape what is established down the line. So choices made at the outset about which aspects of running the new location will ultimately be the responsibility of the home office, and which will be the responsibility of the new site leaders, have enduring importance. Nearly always, the role the home office plays will look significantly different after expansion than before it, regardless of an organization’s program model or the legal relationships it sets up with its affiliates.

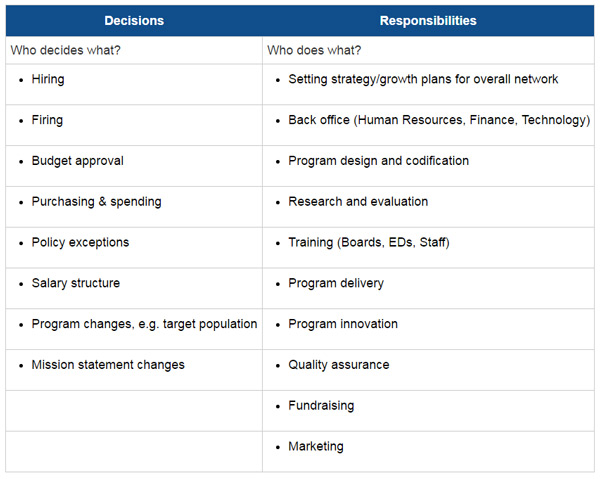

Determining Which Decisions and Responsibilities Should Belong to the Home Office and Which to the New Sites

A useful starting point is to think in terms of the “value proposition” that the center provides to affiliate sites and to the network overall. How can the home office keep the overall strategy on track and provide significant value in addition to what the site can provide on its own? In a sustainable, productive network, the relationship between the center and sites should be symbiotic, with each providing unique value and complementary skills.

The key issues here can be summarized by two broad questions: 1) Who does what: which activities are the responsibility of the center and which are the responsibility of the sites? 2) Who can decide what: which decisions should continue to be made at the home office, and which decisions can be made at the site level? In our experience the answers to these questions are far from uniform. You’ll need to take your own organization’s circumstances into account when deciding what’s best. The accompanying graphic lists the categories where we typically see choices needing to be made:

The New York-based nonprofit, Common Cents, provides a good example. A few years ago the organization, which teaches schoolchildren lessons in philanthropy and service through a city-wide penny drive and other programs, sought to expand its “Penny Harvest Program” to new sites in four new cities. Planning to run this expansion out of its existing NYC site, Common Cents recognized there was a danger of either distracting NYC operations with the new expansion focus, or under-investing in expansion because of the day-to-day demands of the NYC program. The organization handled this by delegating responsibilities and decision-making power to three separate “entities,” NYC affiliate, “National,” or new affiliates, and then clearly allocating staff time against each one, with a plan to add capacity to the national effort as necessary to ensure that each effort maintained its momentum and focus. This enabled staff to be very clear about which "hat" (NYC or National) they were wearing on any given day. National’s responsibilities clearly included things like communications and marketing, whereas sites were to own areas such as school relationships and day-to-day operations. For fundraising, both entities had responsibility, but it was divvied up by size and geography of the funder.

Some organizations find a decision-making tool helpful in making these kinds of choices. There are many available; we’ve seen good results with a tool called RAPID.[5] RAPID helps leaders become clear on not just who is making a given Decision (the “D”), but who is Recommending the course of action, who is providing Input, who has to Approve the decision, and who is ultimately going to Perform the responsibilities based on the decision.

If anything is guaranteed about the center-site relationship, it is that the allocation of decision-making power and responsibilities, and with it the center’s “value proposition” to sites, will need to evolve over time. More than half of the organizations we contacted noted that the services provided by their home office to affiliate sites changed over time, most often in the direction of decentralization. Revisiting the allocation of responsibilities and decisions is therefore something for which every replicating organization should be prepared. Otherwise it can come as a real surprise when maturing sites are suddenly less than satisfied with what may have been exactly the right set of services during start-up. This evolution often takes equal measures of humility and hard work on the part of the center.

In the early years of a replication effort, it is often safe to presume that new sites will depend heavily on the home office. Support in these early stages ranges from tactical to strategic: logistical support for getting the site off the ground, hands-on support and training for inexperienced staff, or assistance with setting up management and governance (see sidebar for a more complete list). Manchester Bidwell Corporation, for example, in addition to all of the supports just mentioned, also commits to helping new geographies identify a pool of Executive Director candidates as well as physical program locations.

Later on, the home office will find it needs to balance supporting new start-up sites with simultaneously serving its maturing sites, which begin to need higher-level forms of support such as branding or best practice sharing. What’s important to know at the outset is that however a given organization structures its services to sites, it should take a learning approach to developing those services over time so it can grow and evolve to meet network needs.

The “value proposition” of the center to sites evolves over time Services to start-up sites often include:

- Back-office management

- Fundraising tools

- Management and governance assistance

- Program materials

- Seed funding

- Staff training

- Technical assistance/ troubleshooting

- Logistical support

Services to more mature sites often include:

- Specific back-office functions (e.g. data systems)

- Best practice sharing

- National partnerships

- Brand awareness

This has been the case for Breakthrough Collaborative, a year-round tuition-free education program for highly motivated, yet underserved youth. Casey Budesilich, National Growth Director, observed this transition in the following way: “Services slowly changed after the first growth period, in a learning moment for the organization. During the first phase of growth, identified best practices were shared across the entire Collaborative. This is resulting in changes to our organizational structure and service delivery model. Now all sites are supported to become ‘growth ready’ as the highest measures of quality and sustainability, even if a site isn’t planning to expand programming. For Breakthrough programs, being growth ready is having consistent, demonstrable outcomes based on strong data, sustainable fundraising and program management, and organizational leadership capable of building strong partnerships. These refinements are the result of researching what made program launches successful, and benchmarking our provision of resources and evaluations against those of other organizations.”

To ensure that this learning takes place, home offices must receive honest feedback from affiliates about what sites truly value from early on—and build this kind of feedback loop into the organization’s DNA. If sites are not themselves forced to make tradeoffs or pay for the services they are receiving from the home office, it is unlikely that they will proactively tell the home office to stop doing something that has become less than valuable, particularly down the line as a network becomes large enough that the home office no longer can maintain close personal relationships with site leaders. The most common ways to gather this information are to have an objective outsider solicit feedback from sites, or to conduct surveys to gather site input. In either case, it is important to push sites on the question of tradeoffs: What is truly valued? What needs are unmet? What should be stopped, started, or continued? One way to simulate these tradeoffs is to ask respondents how they would “spend” a limited set of resources to “purchase” sites from the home office. While sites typically aren’t asked to purchase services “à la carte,” testing willingness to pay in this format can lead to helpful insights about how the home office’s value proposition should be evolving.

Expansion to new locations requires a nonprofit to transform and usually to broaden the scope of activities at its home office. The support and services provided from the center outwards are the primary means by which the existing organization strengthens its affiliates, and often contribute significantly to new sites’ success. Executing this home office transformation successfully requires a thoughtful approach to the underlying responsibilities and decisions, as well as processes for monitoring how the center’s value evolves over time.

Deciding How Funds Should Flow Between the Center and Sites

A related topic—and the source of frequent questions from Executive Directors and Board members—is how to think about the flow of funds between a home office and new sites, especially affiliate fees. In practice, both the expectations and the volume of funds flowing between the center and sites vary significantly across organizations. However, there are a few key principles we suggest keeping in mind.

First, let’s clarify some terminology from the home office’s perspective:

Inward fund flows are typically based on fees paid by affiliates to the home office. In expansion models where a program is licensed to other organizations, this may also include a start-up or initiation fee.

Outward fund flows, or ‘pass-through’ funding, are grants made by the home office to affiliates. These funds provide incentives for affiliate activities that are important to the home office, or for affiliate-specific circumstances, such as financial hardship or demand for growth capital.

Turning to the funding implications of expansion, the experiences of organizations that have struggled with and succeeded at replication suggest that:

There is no one way to set affiliate fees. Not all networks charge fees to affiliates, and, among those who do, they can be set in any number of ways—flat fees, as a percentage of a site’s budget, as a multiple of the number of beneficiaries, etc.

Expansion rarely, if ever, generates net-positive revenue for the home office. Few, if any, home offices earn money through expansion to new sites. Although some expansion efforts create a new income stream through inward fund flows, we find that this income rarely covers the costs of providing services to the affiliates. Of nine organizations we surveyed that charge fees to affiliates, only one covered even 50 percent of its service costs.

Plans for growing affiliates must include a long-term revenue model. It’s common, and healthy, to require new sites to raise a certain amount of money up front. One common pitfall, however, for organizations entering these new locations is the failure to articulate a long-term revenue model, resulting in a funding ‘cliff’ when initial expansion funding ends, often after the first few years. Even if an affiliate is not expected to be self-funding immediately, steps should be taken from the beginning to build the capacity to take over when the time comes. In some cases, this means investing more heavily in site directors and development staff than might appear to be necessary in the short term.

And finally, funding flows can affect the influence the home office has on affiliate site behavior. According to past Bridgespan research, home offices that pass significant funds through to their affiliates (i.e. more than 1 percent or 2 percent of their local budget) often have increased input into the behavior of affiliates, just as any other major funder might. If the money is available, pass-through funds are therefore one way for home offices to maintain a ‘tight,’ coordinated network.

Maintaining Quality

Organizations rarely replicate successfully without struggling with quality somewhere along the way. Fully 70 percent of our survey respondents indicated that maintaining quality at existing sites while opening new ones was a challenge. Replication will test even the strongest of existing operations in new ways. The demand for resources and leadership attention associated with getting new sites up and running smoothly can put extraordinary pressure on the existing organization and threaten quality at the home site. Additionally, when an organization is rushing to meet commitments to open new sites, quality at these new locations can inadvertently take a back seat to the more operational tasks associated with getting a site up and running. The good news is that addressing a short list of basic issues can go a long way toward protecting quality throughout the organization.

Allocating Leadership and Staff Time

Ensuring that sufficient leadership and staff time remain dedicated to the original site is the first issue. Are there enough people—and enough hours in the day—to reasonably expect that both original and new sites will receive enough attention? Manchester Bidwell Corporation hired a new staff person dedicated full time to expansion efforts, well ahead of the actual opening of new sites. This allowed the organization to explicitly limit the percentage of time committed to expansion activities by the rest of the staff. An alternative is to hire dedicated expansion staff from within the organization and replace them with outside hires to ensure that the home site continues to receive the support it needs.

It’s vital to keep up with hiring related to new sites; at the same time, it’s much easier said than done. Aspire began rapidly opening new schools in 2004, with a goal of growing from 10 to 50 schools by 2015. However, the organization was unable to hire additional senior staff to keep up with its expansion, and senior leadership became massively overstretched. Through the course of the expansion, as Aspire CEO Don Shalvey describes it, senior managers were “on the road three to four days a week… certainly we couldn’t devote as much time to our other functions.”[6] Only the creation of a new role dedicated to supporting the field and a lengthy re-clarification of roles allowed the organization to ‘catch up’ with its expansion in a sustainable way.

Allocating Board Time

Like staff, directors may feel stretched during replication. At times, we’ve seen Boards react to the volume of decisions and work by becoming overly focused on expansion at the expense of the home site. Sometimes, we’ve seen the reverse. Boards composed of people with deep local connections and allegiance to the home site may be less engaged with replication in general, and in some cases even lag the staff in terms of adapting to the new responsibilities associated with governing a multi-site organization. Rules of thumb for managing these risks are similar to those that apply for staff. For example, set Board agendas thoughtfully, ensuring that ample attention is paid to both the home and new sites. You might also consider forming a specific Board committee focused on expansion, and directing other Board members to spend their time on ongoing “home-office” issues.

Determining How to Track Performance

Implementing a robust performance tracking system is another quality safeguard. The organization’s leaders need to be able to keep track of the home site in a way that is both objective and separate from the performance of the new sites. At the same time, they need to ensure that new sites are put on a trajectory to high quality from day one, and that their results are measured as well. Nonprofit leaders often pass over investments in tracking technology, especially early on, when money tends to be tight and management preoccupied with other work.

A Bridgespan study on the growth of youth-serving organizations,[7] however, found that the later an organization made performance measurement a part of its culture, the more disruptive the process was.

The benefits of building a strong tracking system, or adapting an existing one, are significant in the eyes of experienced leaders. We’ve found that the organizations that address performance tracking most successfully weave it into ongoing management efforts. At CAS-Carrera’s Adolescent Pregnancy Prevention Program, the tracking system allows senior staff to view an “administrative dashboard” with up-to-date statistics from each affiliate site. Founder Dr. Michael Carrera noted, “Robust IT provides tremendous value [in our ability to maintain quality across sites].”[8]

But there are pitfalls to be aware of in setting up an effective system. Launching a system that is too complicated to use is one. Implementing a system that asks for more detail than can be readily provided by sites is another. The National Academy Foundation (NAF), a New York-based organization that supports targeted career-themed programs in high schools around the country, developed a comprehensive data collection platform to collect and track several dozen site performance metrics. NAF’s affiliate high schools, however, typically provided only a subset of the data requested, resulting in numerous unpopulated fields and hindering analysis and reporting efforts. To address this issue, NAF is currently in the process of streamlining its requirements to emphasize reporting on a significantly smaller number of performance indicators, and believes that this focus on critical metrics coupled with enhanced network communication will dramatically improve compliance rates.

Ideally, tracking systems enable the home office to keep a close watch over local operations and intervene when necessary, but are minimally overbearing or invasive. At Boys Town, for example, senior management at the home office in Omaha receives basic daily event reports from each of its remote sites. If major events requiring follow-up action occur, this process ensures that the relevant home office staff member is alerted immediately. Over time, the home office responds to longer-term trends revealed through these reports with targeted troubleshooting, training, or management adjustments as necessary.

Non-program metrics are also important. While nearly every organization we surveyed tracks key program metrics, non-program metrics were measured less frequently. For example, only about a third measured staff satisfaction or retention. Based on our experience, organizational capacity should receive just as much attention as program performance: when programs show signals of poor quality, closer examination of performance often reveals a subscale or otherwise flawed local organization failing to provide adequate or appropriate support. Considering what a new site needs to survive in the short term, therefore, needs to be assessed hand-in-hand with what it will need to grow and scale successfully in the future. While reinforcing your new sites’ organizational capacity may not be as exciting, or feel like quite as much progress as when you kick off the program itself, you’re likely to be rewarded in the long run.

More than three-quarters of the organizations we surveyed reported that it typically takes more than a year for program quality at new sites to reach the level of the original site. It also takes time for the original site or sites to regroup and gain a new momentum. Patience, in the face of steep learning curves and the day-to-day trials of replication, is often in short supply, and the temptation to second-guess your course can be strong. But keeping your end-goals in mind can help you assess accurately whether the problem you’re facing today simply needs time and effort to sort itself out, or if it is something more serious.

The Importance of the Long View

Ultimately, the time that you invest addressing these few, very important decisions should pay off in terms of your organization’s ability to do right by new beneficiaries, while continuing to serve existing beneficiaries as well, or better, than you did before.

As MY TURN’s chief executive officer Barbara A. Duffy put it, “We learned very quickly that we needed to face tough decisions head on and vet them thoroughly, knowing that each decision we made would help to build a strong foundation for growth and provide confidence throughout the organization that we would be well-positioned for the road ahead.”[9]

Sources Used for This Article

[1] In February 2008, Bridgespan surveyed Executive Directors and other senior executives involved in the replication efforts of 14 multi-site 501(c)(3) organizations in the education, youth development, and workforce development fields. The majority of those surveyed began replication in the last 15 years, and have subsequently grown to five or more sites.

[2] Summer Search 2006 Annual Report

[3] Nurse-Family Partnership Fact Sheet [PDF]

[4] The development of a strategic plan that projects Nurse-Family Partnership’s long-term sustainability has been critical to both clarifying its economic model and raising philanthropic funds to support growth.

[5] “RAPID decision-making: What it is, why we like it, and how to get the most out of it” by Jon Huggett and Caitrin Moran.

[7] Bridgespan study: Growth of Youth-Serving Organizations

[8] Interview with Dr. Carrera, Feb. 2008

[9] Shortly after the completion of this article, Barbara Duffy stepped down from her position as CEO of MY TURN after 24 years of service.