“What gets measured gets managed.” This old adage applies to nonprofits, too, and it may explain why performance measurement is becoming more prevalent in the nonprofit sector. Funders propelled much of the early buzz about measurement, seeing it as a way to keep tabs on what their grantees were doing with their money. But, funder pressure aside, more and more nonprofit leaders are seeing performance measurement as a valuable management tool for achieving greater impact.

At the same time, performance measurement can get very complicated very fast. It’s remarkably easy to get hung up trying to collect measures that won’t really tell you very much. Moreover, some things can’t be quantified easily. According to a recent study by the Independent Sector, nearly 60 percent of nonprofits surveyed said that the results of at least some of their programs were too intangible to measure.* These challenges are particularly acute for organizations like the Great Valley Center (GVC) that have highly ambitious social and environmental goals.

When GVC secured funding in 2002 to add six new programs, performance measurement became paramount for Carol Whiteside, GVC’s president. It was apparent that she and her management team no longer could rely on an ad hoc approach to keeping a pulse on the organization. They needed a simple yet systematic method for determining whether GVC was on track to have the impact they’d intended and for sharing results with key stakeholders. Whiteside asked the Bridgespan Group to help her organization construct a new performance measurement system that would satisfy these needs.

At the conclusion of our engagement, GVC and Bridgespan had struggled jointly (and in large part succeeded) in finding the right level of performance measurement for the organization as a whole and for each of its programs. Along the way, we discovered that the process of putting measures in place also increased GVC’s strategic clarity, because it required Whiteside and her management team to articulate the impact they hoped to create, and to pinpoint which results were under their control and which ones they might contribute to but could not take responsibility for. It was also a great way to reality test their theory of change—the cause-and-effect logic that linked each of their programs to the impact they hoped to achieve. Last but not least, we were reminded of some performance measurement fundamentals: that the effectiveness of some programs is easier to measure than others; that measures need to be simple to gather, maintain and use; and that good performance measurement is often a combination of qualitative and quantitative information.

The Great Valley Center

The Great Valley Center, located in Modesto, California, is a nonprofit organization that promotes the economic, social, and environmental well-being of California’s 450-mile long Great Central Valley. This mission is exceptionally ambitious considering the enormous strains on the Valley, a region that has long been overshadowed by California’s two better-known coastal regions—metro Los Angeles to the southwest and the San Francisco Bay Area to the west. Not only is the Valley one of the state’s most diverse regions, but it is also its fastest growing, with demographers expecting its current population of just over 6 million to soar beyond the 12 million mark by 2040.

This rapid growth has brought numerous challenges, all made very evident to Carol Whiteside during her long and successful career in California public service. With her sights set on making the Valley a better place to live, Whiteside created GVC in 1997. Specifically, she envisioned GVC working towards four goals:

- A sustainable, productive region that supports a good quality of life

- Economic development that builds on the Valley’s strengths

- More effectively engaged communities

- Policy-making that values environmental quality

To make progress against these goals, GVC began by re-granting funds from major private foundations to nonprofit and public sector organizations within the Valley. However, Whiteside and her management team soon recognized that more would be needed to achieve their vision—in particular, there were few if any organizations with programs that sought to improve issues Valley-wide. To meet that need, over the next four years they designed and ran six programs that focused on: understanding and promoting the use of technology to facilitate the Valley’s economic development; training new groups of leaders for the Valley’s future; and creating innovative economic techniques that would encourage agricultural land conservation as the Valley grew.

At the start of 2001, GVC submitted a proposal for a multi-year initiative to The James Irvine Foundation and The William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, two of its early funders and strong supporters. This initiative would add six new programs to GVC’s original roster. In the process, it would increase dramatically the scope and ambition of the organization’s activities designed to strengthen community efforts devoted to children, youth, and families. GVC was successful in getting the initiative funded and received $9.5 million over a three-year period from the two funders. Irvine’s support alone equaled the largest single grant the foundation had ever made.

At this point, Whiteside recognized that the management challenges she and her team were facing would escalate several fold. If GVC were to grow effectively and to achieve the impact they desired, they continually would have to assess the progress they were making against their four goals. Reliable data with which to understand how each of GVC’s programs was performing would allow GVC management to make sure that problems could be identified and resolved early—a check that would be particularly important for the programs they were just instituting. At the organizational level, they intended to use the data to help them test and refine their overall strategy for impact as well as to make sure the organization was providing the support individual program teams needed to be successful. Whiteside asked Bridgespan to help GVC build a performance measurement system that could take them into the future.

Critical Questions

In working together with GVC to set up a performance measurement system, we sought to answer the following critical questions:

- What approach to performance measurement would help GVC not only to manage day-to-day operations but also to ensure that they were working towards their long-term goals?

- Within this approach, what were the right measures, at the program and at the organizational level, to assess GVC’s performance?

- How could GVC collect this information without creating an undue burden in staff time or organizational cost? What was the right frequency for collection and review, and who should be involved at each stage?

Crafting a Performance Measurement Framework

Designing and using a performance measurement system consumes time and resources that could otherwise be applied toward having impact; the GVC/Bridgespan team was acutely aware that our approach needed to be worth the price. Moreover, our goal was to help GVC to make better management decisions and to share results with key stakeholders – a less rigorous hurdle than those inherent in building systematic evaluation programs. A good performance measurement system, in our minds, would sacrifice perfection for pragmatism, be affordable to maintain, and, above all, be easy to use. It would be far better to have good-but-imperfect indicators of performance than to divert the organization’s attention, breed overall cynicism about measurement, and—by trying for something that may be unattainable—drive GVC staff ultimately to throw in the towel.

In our search for a practical approach to performance measurement, we surveyed the latest thinking on how others proposed to assess nonprofit performance. We found numerous thoughtfully developed frameworks. Ultimately, we adapted our framework from one used by the United Way.

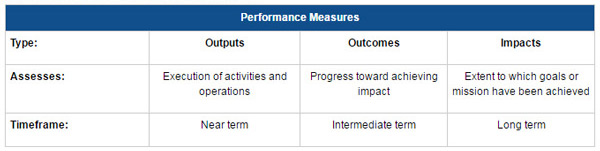

At the core of the approach is the concept that performance should be considered along a time continuum, beginning with the direct and immediate results of program activities (outputs) and continuing through to the benefits for the participants during and after the program activities (outcomes). This framework dovetails with two concepts Bridgespan employs to help translate bold and inspiring mission statements into practical strategic guideposts, bridging the gap between a nonprofit’s mission and its day-to-day activities and programs: intended impact and theory of change. Briefly, a nonprofit’s intended impact is a statement about what specifically it is trying to achieve and will hold itself accountable for within a manageable period of time. Its theory of change lays out its understanding of how that impact will come about—what the organization, working alone or with others, must do to achieve real results.

Bringing this back to the approach to performance measurement, longer-term outcome measures (or what we came to call impacts) let an organization check that its theory of change indeed is creating its intended impact. If not, it’s time to adjust the theory of change. Near-term outputs help an organization ensure that it’s executing well against each of the activities that make up its theory of change. And since impact can be long in coming, intermediate-term outcomes serve as early indicators of longer-term results, thereby allowing for mid-course corrections. (Please see Exhibit A for an overview of these performance measures.)

Exhibit A: Performance Measure Overview

Take the example of an after-school child-mentoring program with the mission of increasing the odds that kids grow up to earn living wages. The number of children mentored would be a near-term output. The percent of these children who went on to graduate from high school would be an intermediate-term outcome. The percent of participants who were employed in living wage jobs at age 25 would be long-term impact.

This same framework can be applied to individual programs as well as to the overall organization. Measuring at the program level helps to ensure that the individual programs are on track. Measuring at the organizational level provides insight into whether or not the organization has the right set of programs to achieve its overall intended impact (i.e., that the organization’s theory of change is correct) and the right infrastructure in place to support these programs. Accordingly, we set up measures on two paths. We collaborated with each program manager to apply the framework to his or her specific program and we went through the same process for GVC overall with Whiteside and her Chief Operating Officer.

We began by defining the near-term output measures because we expected they would be the easiest to decipher. Next we proceeded to the other end of the spectrum to establish long-term impact measures, since we knew that Whiteside and her team had already put a lot of thought into the changes they hoped would result from their work. The intermediate-term outcome measures—the links between the near-term outcomes and the long-term impacts—were saved for last since we thought these would be the hardest measures to identify.

Defining Program Measures

Our work with one of GVC’s newer programs, the Great Valley Leadership Institute (GVLI), offers an example of how the performance measurement framework can be applied at the program level. Established in partnership with the Kenneth L. Maddy Institute of Public Affairs at California State University, GVLI helps local leaders improve their decision-making skills, thus enabling them to become stronger stewards for their communities as well as more thoughtful, successful leaders.

Twice a year, GVLI brings together approximately 30 accomplished elected officials—mayors, city council members, and county supervisors—from across the Central Valley. Out of a pool of candidates nominated by Valley residents, GVLI staff chooses individuals with sound leadership skills and strong potential for future contribution to their Valley communities. Prominent leadership experts from the faculty of Harvard University’s John F. Kennedy School of Government then guide this carefully selected group through a rigorous five-day leadership course.

Near-term Output Measures

Since outputs measure the immediate results of program activities, the GVC/Bridgespan team found that the most logical place to start defining outputs was to identify the core processes that were key to GVLI’s success. These processes included:

- Pinpointing a high-caliber and diverse group of elected officials suitable for nomination to the program

- Reviewing nominations and selecting appropriate participants

- Conducting the program sessions and covering all the topics that were critical to the curriculum

We then looked for output measures to assess how well GVLI was executing against each of these core processes. Measures had to involve data that GVC could collect easily, and they also—not surprisingly—had to tell us something useful. Key performance criteria passing these two tests included the number of officials nominated to the program as well as the acceptance rate by nominees. Measures that dropped out included those that were too arbitrary and difficult to measure (e.g. were the sessions conducted well?) and those for which performance would be so obvious that it didn’t need to be tracked (e.g. were the sessions actually conducted?).

Long-term Impact Measures

Next we worked out how to measure GVLI’s long-term impact—the extent to which GVLI would be successful in achieving its goals in five years or more. It’s critical that at the program level these measures of impact are something that the program is willing to hold itself accountable for achieving. We selected GVLI’s specific impact measures from two broad categories of impact:

Since GVLI staff planned to keep in contact with alumni, they could collect data on these two categories of impact as part of ongoing alumni relations. The challenge would be to keep costs low so we emphasized economical approaches, including online surveys and self-reporting.

We considered many other measures of GVLI impact but discarded them because the data would have been too difficult to collect or would not have been something that GVLI reasonably could consider itself responsible for influencing. For example, although it would have been ideal to know whether GVLI graduates were making “better” decisions as a result of their participation in the program, the highly subjective nature of evaluating decision-making quality would have made such efforts costly and of questionable credibility.

As we worked to establish our set of impact measures, we were reminded of an essential aspect of measuring performance—one that we carried with us throughout the remainder of the process: quantitative measurement of performance shouldn’t take the place of “stories.” While it may be tempting (at least for some) to try to reduce the performance of a nonprofit organization to sterile facts and figures, what draws most of us (nonprofit leaders, staff, and funders) to the social sector is a passion to improve the lives of real people. As such, it’s critically important to stay in touch with how the organization’s work affects the people it serves.

GVC’s staff, for instance, collected stories from their programs and reviewed these anecdotes regularly with GVC’s board, funders, and fellow staff members. These stories reminded them of how their work benefits the lives of people in the Valley and also allowed them to mine for ideas on how GVC could serve its beneficiaries better. We extended this commitment to qualitative measurement and included a means for recording stories about the impact of each of the programs in the overall performance measurement system.

Intermediate-term Outcome Measures

With the near-term output and long-term impact bookends established, we moved on to intermediate-term outcome measures. GVLI’s impact wouldn’t be known for many years, creating a clear need for something more intermediate in nature to determine whether the program was on track. Outcome measures link outputs with impact, have a timeframe of perhaps one to three years, and most important, must be measurable.

Although defining outcome measures turned out to be difficult—and, in fact, downright frustrating at times—we found it was the most valuable aspect of our work since it compelled a discussion about GVLI’s underlying theory of change. We were forced to ask the question: why do we believe GVLI’s activities (outputs) are likely to bring about the change GVLI seeks to create (impacts)?

We broke down GVLI’s theory of change into three components:

To test this theory of change, we looked for outcome measures that would assess whether the GVLI experience benefited participants’ public service careers and if participants and the broader Valley community recognized the GVLI as a valuable leadership program. To measure the benefit of the program, at 6- and 12-month increments after graduation GVLI staff would interview alumni, asking how they approached problems differently because of the GVLI program and what new collaborations they had formed as a result of the GVLI network. To get an indication of the perceived worth of the program, they would also ask alumni to rate the program’s value. We were careful to set modest (yet sufficient) goals for the number of alumni interviews staff would conduct, given that interview-based measurement tends to be quite costly. Beyond these interviews, staff would track the growth in the number of nominations as an indicator of how GVLI’s reputation was growing.

We followed the same three-step process for each program in the GVC roster and developed a set of output, outcome, and impact measures for each. In every case, the process was time consuming—approximately 10 hours with each program manager or director—and setting up acceptable and appropriate measures for each program had its own unique challenges. (Please see the Appendix: Some programs were harder than others to measure.)

It is important to note that benefits from discussing and defining outputs, outcomes, and impacts went far beyond the performance measurement system itself, as the process also enhanced GVC’s strategic clarity and program alignment. Several program managers found that they needed to refine their program designs, because thinking through performance metrics prompted them to question whether their program activities could in fact deliver the impact they intended. In other words, the process helped them to pressure test and to refine their theory of change.

The managers of GVC’s Institute for the Development of Emerging Area Leaders (IDEAL) program, for example, did just that. Since IDEAL’s mandate is to develop Valley leadership from within the underrepresented and minority adult population living in small, rural communities, they defined obtaining the proper ethnic mix for their incoming classes as a key near-term output measure. In doing so, they realized that it made sense to reduce the overall class size to ensure they had the right mix given the potential pool of applicants. In short, the process led them to have greater clarity on what they were trying to accomplish and how they might get there.

Establishing Organizational Measures

Concurrent with developing performance measures for each of GVC’s individual programs, the GVC/Bridgespan team worked to establish a set of organization-wide performance measures that would allow GVC management to test and refine their overall strategy for impact. We applied the same approach we had used with the programs, again starting with short-term outputs, skipping to long-term impacts, and ending with intermediate-term outcomes.

Short-term Output Measures

For GVC’s programs, we had based our output measures on key program activities. The organizational analogs were the umbrella support services that GVC provides, those processes that are the foundation for delivering each and every program. Without them, and indeed without the basic infrastructure of GVC, the individual programs would not be able to deliver on their objectives. We identified four such services:

- Finance: Raising funds and managing the budget

- Operations: Keeping the lights on and the computers running

- Staff learning and growth: Training and developing GVC staff

- Community outreach: Getting the word out about GVC

For each support service, we identified a small set of outputs to track. For example, one of GVC’s priorities was broadening its fundraising to include more governmental and individual support. Therefore, measures to capture these dimensions were included in the set of financial outputs. As another example, GVC was renovating a building to accommodate their expanding staff. Accordingly, we included operational performance measures to monitor the progress of these renovations. We established targets for each measure and corresponding mechanisms for collecting the necessary data.

Long-term Impact Measures

Next we identified the organization’s long-term impact measures. Here we had the advantage of having worked with Whiteside previously to articulate GVC’s strategy. The result of that work was a crystallization of the four statements of impact that she envisioned for GVC (shared earlier), which related to the regional, economic, social, and environmental well-being of the Valley. Each statement had an associated theory of change for how that impact would be accomplished.

We identified a set of measures that would assess progress toward each of these impact statements, choosing measures that directly related to GVC’s theory of change. Keeping in mind our charge to make the performance measurement system practical and cost-effective, we focused squarely on impacts for which data was available—either through GVC’s own research or through published data sources (e.g., GDP growth data, total acres of land in conservation in the Valley).

As we proceeded, we realized that establishing GVC’s organizational impact measures was going to be tougher than anticipated. At the program level, we had struggled but, in the end, we were largely successful in identifying ways to measure impact. At the organizational level, the task was much more difficult. GVC is a complex multi-program nonprofit with ambitious goals for a large geography. The measures of GVC’s impact that we considered, in most cases, were affected by such a broad array of forces—including overall state and national economic conditions—that GVC couldn’t consider them to be an accurate assessment of their own performance.

This challenge did not deter GVC from measuring organizational impact—nor should it have. Whiteside and her management team didn’t want to ignore these “external” measures because they were important indicators of the conditions of the Valley that GVC was hoping to affect. The solution was to differentiate between those measures for which GVC might reasonably hold itself directly accountable and other, more macro-level measures of the Valley’s well being. This distinction allowed us to create both a set of organization level measures that tracked GVC’s direct impact as well as the very important indirect (macro-level) impact GVC hoped to achieve. (Please see Exhibit B: GVC’s Organizational Impact Measures.)

Exhibit B: GVC’s Organizational Impact Measures

Whiteside and her team saw great value in understanding how the broader environment they sought to impact was changing. Even though they couldn’t see directly the impact of GVC’s work in the macro-level measures they monitored, they could tell whether or not progress was being made. If progress weren’t being made on these macro-level measures, then, over time, GVC would need to reevaluate its theory of change and reason for being.

Intermediate-term Outcome Measures

While defining outcome measures had been the hardest part of our program-level work, at the organizational level these were the easiest to delineate. All it took was recognizing that the links between GVC’s organizational outputs (the core processes that support GVC’s portfolio of programs) and the impacts that GVC seeks (the cumulative results of each of these programs) are the programs themselves. Therefore we decided that the organization’s outcome measures were really the sum of the programs’ impacts.

The Ongoing Measurement Process

With the performance measures for both the programs and the organization chosen, we set up a process for data collection and review. Ongoing data collection became the responsibility of each program assistant; each program manager would—on a quarterly basis—meet with the COO to review performance and discuss implications for program design or execution. GVC’s board would assess organizational performance measures yearly. The entire slate of performance measures would be examined annually and, based on their usefulness for decision-making and their ease of collection, would be revised as necessary.

Although this cycle makes sense for GVC, the appropriate time frame will differ within each organization depending on the nature of a nonprofit’s programs and goals. The right interval for collecting and reviewing measures should be the shortest possible time frame in which meaningful performance data can be collected.

Lastly, we developed an Excel-based workbook, with a worksheet for each program that included performance measures (outputs, outcomes, and impacts), targets and areas where actual performance data would be entered. The workbook resides on a shared drive on GVC’s computer network where everyone in the organization can access it. However, each program’s worksheet is protected so that anyone other than its owner can’t inadvertently change the data.

Results

As of the publishing of this case study in December 2003, Great Valley Center’s ten months of experience living into their performance measurement strategy had served to solidify what we learned in the development process. They were enjoying a clearer vision of how their day-to-day activities were helping them to make progress toward their mission. As a Program Director explained, “Establishing performance measures really forced me to think about my programs. I now have more clarity about the programs and the impact they seek to achieve.” GVC management also appreciated the value of the measures in keeping the organization moving towards its goals. In the words of one Program Manager, “Performance measurement helps keep us on track.”

The implementation process reinforced the importance of the simplicity mantra the team had evoked throughout the development process. Programs with somewhat more complex or more nebulous data collection mechanisms lagged behind those with simpler measures. For example, figuring out a way to keep in touch with alumni proved to be more challenging than anticipated and so the implementation of the measure had been delayed. And while GVC management was steadfast in their belief that stories should also be legitimate in measuring organizational impact, they were finding that the collection process was not yet as structured as it needed to be. As GVC’s COO noted, “Performance measures are incredibly useful. The big challenge is the time it takes to collect them. Simplicity is key if you want them to be used.”

By all accounts, GVC continued to learn from the process. As staff created a track record and established benchmarks, they were seeing the usefulness of metrics increase. And given their strong belief that the process of devising the measures was illuminating in itself, they were considering having their new managers go through a similar metric development exercise.

Appendix: Some programs were easier than others to measure

Certain programs and activities lent themselves better to performance measurement than others. Programs that deliver a service, such as GVC’s Central Valley Digital Network technology training program, seemed to find the greatest value in the performance data once it was collected. We reasoned that this was perhaps because they were engaged in predictable and repeated activities, making it easier to make improvements and to observe the attendant results.

In contrast, both the design and use of performance measurement was tougher for programs that, rather than delivering a service, aim to change policy. A case in point was GVC’s New Valley Connexions (NVC) program. NVC seeks to strengthen and the regional economy of the San Joaquin Valley by advancing new technologies and positioning the region to be more competitive. NVC relies heavily on collaborations and partnerships, and responds to frequent changes in the actions of state and private entities. For NVC, output measures quickly became outdated because external policies and strategies changed. Measuring NVC’s activities over time made little sense because few of the program’s activities were repeated. Outcome measures were also hard to define because evidence of progress toward such a large-scale impact was influenced by a multitude of other factors.

For programs like NVC that were about policy change, we allowed the output metrics to be set at a slightly higher level (e.g. number of reports prepared and delivered) and more descriptive (percentage of event attendees from the business sector). This gave NVC more flexibility and, in so doing, reduced the sense of constraint that the metrics had caused for programs that were more fluid.

[*] As reported in the Chronicle of Philanthropy’s October 31, 2002 article, “Most Charities and Religious Groups Evaluate Programs, Report Says.”