[TPL takes a] pragmatic, flexible outlook. We are not confrontational or ideological in the process we use.

– Felicia Marcus, Chief Operating Officer

Overview

Related Content

How Nonprofits Get Really BigOrganization Profiles from How Nonprofits Get Really Big

Founded in 1972, the Trust for Public Land (TPL) conserves land for people to enjoy. It does so by helping communities raise funds for conservation and by facilitating transactions that move land from private landowners to public agencies in the U.S. TPL is a national organization made up of regional and local offices and state advisory boards. It is managed by a national office in San Francisco under the oversight of a national board of directors.

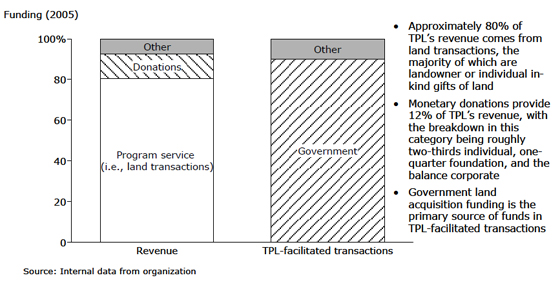

TPL’s position as an environmental nonprofit with expertise in land transactions makes it an important part of the “value chain” that moves land from private hands to public agencies. TPL buys land from willing, private sellers at or below market prices and sells it to public agencies at or below market price. TPL supports itself through donations from landowners either in the form of cash or land value donated to TPL. Public agencies occasionally pay TPL a fee for facilitating the transaction. TPL adds value for the government by: identifying important land for conservation; responding quickly in a dynamic real estate market; putting together complex multi-agency public and private funding partnerships; arranging often complex deals; holding the land while a government agency arranges funding; and acting as intermediary where sellers prefer not to deal directly with government agencies.

In the mid-1990’s TPL began “conservation finance” efforts, running state and local bond measure campaigns to increase funding for land conservation. These efforts advance TPL’s mission by raising awareness and money for conservation generally, and also provide revenue to government agencies that purchase land through TPL.

To date TPL has helped generate over $35 billion in land-conservation related funding through ballot measures, and has facilitated approximately 2,700 land transactions. TPL handled $500 million in land transactions in 2004.

Founding date: 1972

Revenue (2005): $62 million

Structure: Single organization with local advisory boards

NCCS classification: Environmental beautification

Services: Facilitates land conservation transactions; runs "conservation financing" campaigns for local communities; helps define conservation priorities for communities; engages in research and education

Beneficiaries: The public at large; park and recreation users

Leadership (selected): Will Rogers, Chief Executive Officer; Felicia Marcus, Chief Operating Officer

Address: 116 New Montgomery St., 4th Floor, San Francisco, CA 94105

Website: www.tpl.org

Growth Story

- 1972 – TPL is founded. Initial programs included a federal lands program supported by landowner donations and an urban parks program supported primarily by foundation support and to some extent cross-subsidized by donations from its federal lands program.

- 1982 – The Reagan administration cuts land acquisition funding, sending TPL scrambling for alternate conservation funding sources. Federal funding previously had provided 70% of its transaction funding.

- 1984 – The TPL board institutes a six-month operating reserve target.

- 1990 – A major bequest jumpstarts the operating reserve fund.

- 1991 - 1992 – Inaccuracies in TPL’s revenue forecasting result in a $2 million shortfall. Management retools its approach to forecasting process, introducing a bottom-up probabilistic forecasting process from field offices. The change results in better forecasts of the likelihood and timing of transactions.

- Mid 1990s – TPL moves into the “conservation finance” arena, helping agencies and communities raise public conservation funding at the state, county, and local level, generally through voter-approved initiatives. These activities increase the conservation funding pipeline and allow TPL to conserve more land.

- 1996 – TPL begins its first bond measure campaign to generate additional land conservation funds in localities.

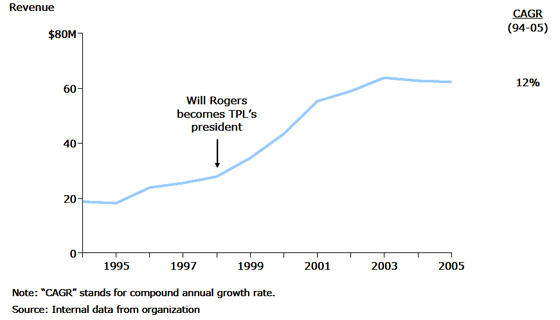

- 1998 – Will Rogers becomes president and makes growth an explicit goal for TPL.

- 2003 – TPL redefines its operating reserve policy to take into account both available operating cash and projected releases of foundation grants, resulting in a reserve target somewhat lower than its former goal of six months.

Revenue Trends

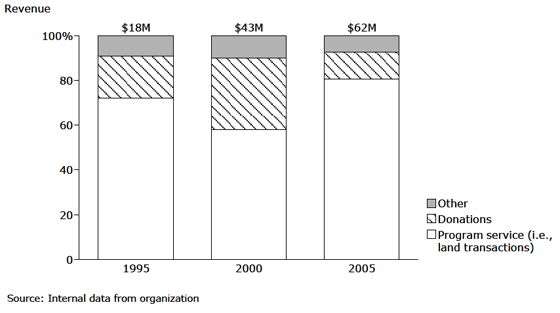

Revenue growth: Revenue growth has increased in the late 1990’s with the conservation finance program and the introduction of growth as a goal.

Funding mix: The majority of TPL’s revenue has come from the landowners with whom the organization works on transactions, with the balance coming from other philanthropy, fees, and investment earnings.

Actions That Helped Propel Growth in Funding

- Emphasized local relationships. Since conservation is a fundamentally local pursuit, TPL has established 24 regional boards and relies on local offices to establish relationships with local landowners, policymakers, and philanthropists.

- Made a conscious commitment to growth. TPL did not grow significantly until it made doing so an explicit goal. When Will Rogers came to the helm, he stressed that TPL’s mission could not be realized without substantial growth.

- Focused on building financial stability. Realizing that transaction-based revenue comes in bursts, TPL created a six-month operating reserve in 1984, using a major gift to kickoff the policy. Operating reserves have allowed the organization to pursue an aggressive growth strategy without risking its long-term viability.

- Took a pragmatic, results-oriented approach. TPL became known as an honest broker more interested in helping its partners (both sellers and buyers) than in advancing a particular agenda. It did so by building a capability to arrange very complex deals that meet the needs of private sellers and large government entities.

Funding Challenges

- Riding the real estate market. TPL must wait for land to become available (rather than offer an above-market price) to conserve land. And because TPL cannot manage land indefinitely, it relies on public agencies to be good stewards of land.

- Balancing varied interests. TPL works hard to balance both local and national interests, given that its model requires engagement at both levels. Similarly, the organization must avoid getting “too political” with its messaging, so as not to jeopardize its broad spectrum of relationships and the government monies which are the primary source of funding for its conservation real estate transactions.

- Maintaining target reserves. Growth through the 1990’s shrank TPL’s operating reserves as a percentage of revenue, dropping them below TPL’s then six-month target and requiring greater operating surpluses to build reserves.