National networks are a fixture of today’s nonprofit landscape. Consider the youth-development domain, in which the 10 largest networks receive over 50 percent of the direct-service funds. By sheer scale alone, national networks represent an enormous resource to society. It’s hard to imagine how America will get the upper hand on problems such as truancy, juvenile crime, and teen pregnancy without them.

Mobilizing the power of national networks is no simple task, however. Assembled over decades as local sites sprang up across the country, 50- year-old sites exist alongside brand new ones. Programmatic variations abound, the result of sites customizing their programs to meet local needs.

Communities in Schools (CIS) is one of these complex—and high-potential—national networks. Its origins trace back to 1977, when Bill Milliken started a small organization that connected public schools with community resources to help young people successfully learn, stay in school, and prepare for life. Years of rapid growth gave rise to a diverse network of over 200 local affiliates in 28 states, operating in more than 3,000 schools. Early in 2004, Milliken, his management team, and national board committed to propelling the network forward. They worked together with the Bridgespan Group to create a business plan that would pave the way.

Communities in Schools at a Glance

As a child, Acton Archie moved from one government housing development to another – 12 times in 12 years, in fact. His father was murdered when Acton was in the second grade; his mother was a drug addict. Each day was a struggle, waking up with no power or water in the house, and walking past drugs and crime on the way to and from school.

In his early teenage years, Acton made some bad choices and was headed for dropping out of school until an organization called Communities in Schools (CIS) provided a helping hand. The CIS coordinator at Acton’s high school made sure he had transportation to school, dental and health care, and connections to community support personnel. She also became a mentor and a friend. He learned about college and career options and received encouragement to form goals for himself. “I probably would have dropped out without that support,” he reflected.

Acton’s childhood is not unusual. Over the last several decades, reported dropout rates have hovered between 11 and 14 percent,1 with students struggling to find the confidence, support system, and motivation to stay in school. One man, Bill Milliken, grew frustrated with this picture and decided to do something about it. He believed that kids needed “the five basics” to be prepared for life: a personal relationship with a caring adult, a safe place, a healthy start, a marketable skill, and a chance to give back to their community.

To address these needs, in 1977 Milliken started CIS, initially serving one school in Atlanta. Leaders in other cities and states soon heard about CIS and wanted to begin CIS affiliates in their own communities. Milliken shared his vision, and CIS spread throughout the country, forming a national network.

Documented proof that the CIS model worked accelerated the network’s momentum. More than 75 percent of kids who received direct CIS support realized improvements in attendance, behavior, and academic achievement; nearly 90 percent either graduated or advanced to the next grade; and only 1 percent dropped out. In both 2002 and 2003, CIS was selected by Worth Magazine as one of “100 Charities Most Likely to Save the World.” By 2004, CIS was directly serving nearly one million children annually.

Despite this extraordinary success, CIS like many national organizations struggled to coordinate the efforts of its network. CIS local affiliates varied widely in size, age, and programming, which made it difficult for the national office to meet their needs. At the same time, Milliken, his management team, and board believed that CIS was in position to move the needle on youth issues; they had a 50-year vision of creating permanent institutional change and transforming communities. Anxious for CIS to realize its full potential, they teamed up with the Bridgespan Group to create a business plan for the entire network.

Key Questions

Over a period of seven months, a project team consisting of President Bill Milliken, Executive Vice President Dan Cardinali, two additional CIS national managers, a strategic planning committee of six national board members, and a team of Bridgespan consultants collaborated to answer the following questions:

- What did CIS – the national office and the entire network – want to achieve?

- What roles did the national office, state offices, local affiliates, and board need to play to realize these goals?

- How could the entire system make this change happen? What organizational changes would it take to align the organization around a new strategy?

Clarifying the Network’s Strategy

Depending on whom you asked, the question, “What does CIS do?” would elicit widely different answers. In fact, a common phrase around CIS was, “If you’ve seen one CIS, you’ve seen one CIS.”

Faced with the challenge of energizing the entire network, the project team knew they had to establish greater clarity around the impact CIS wanted to have and how it intended to achieve that impact. Rather than dilute efforts across multiple goals and activities, the entire network would need to work towards a common goal with a consistent approach.

The first step was to specify what that goal and approach would be. Past CIS strategic-planning efforts largely had failed, a performance Milliken attributed in part to insufficient network involvement; the plans came down from National, and buy-in suffered accordingly. CIS was committed to making this planning process different, and that made securing input and participation throughout the network and from the board a must. While the national leaders would start by putting a stake in the ground, they then would open the process up to extensive feedback from the local affiliates, state offices, and board members.

What is the Impact CIS Wants to Create?

To crystallize a common goal, CIS had to nail down two key elements. Who, exactly, should be the primary beneficiary of CIS’s services? And what impact did CIS hope to create for them? These questions had several potential answers, and each would imply a different set of strategic priorities.

Since all the local affiliates were helping kids, specifying CIS’s target beneficiary seemed straightforward. But complexity lurked beneath the surface. Should CIS target only the kids who were enrolled in its programs, or did it want to help all students in a given school? Moreover, many CIS leaders believed that the organization did far more than help kids. Countless anecdotes illustrated that CIS also helped families, teachers, and school systems.

To elucidate their beliefs, the national leaders asked themselves the following questions about each of the groups CIS could serve:

- Do we want to be held accountable for changing this group?

- If we can’t measure any change in this group will we consider CIS a failure?

- Are we willing to allocate resources – time and money – towards serving this group?

They started with the tightest definition: kids enrolled in CIS programs. The answer to all three questions was a resounding “yes.” But there was a sense among them that this degree of focus was too narrow – that they wanted CIS to be on the hook for more.

They expanded the set to include students who attended schools where CIS had a presence, but who were not enrolled in the CIS program. The size of this group varied from school to school, as CIS affiliates offered direct services to anywhere between 10 and 100 percent of a school’s students. The national leaders believed CIS could make a difference for all the kids in their schools, because by helping the kids enrolled in CIS programs learn, prepare for life, and stay in school, CIS had a positive effect on every student. Data backed them up. Their research showed that improvements in attendance, behavior, and achievement occurred throughout the entire school.

When they extended the beneficiary definition even further, however, to include teachers, families, and school systems, they quickly realized they had moved too far. While the national leaders believed the positive benefits of CIS programs extended beyond a school’s students, they did not think that this impact was something they could track reliably or attribute definitively to their programs. Moreover, they were quite certain that if additional resources became available, they would direct them toward the students. With that, the working definition of their beneficiaries became all students in schools where CIS has a presence.

Multiple options also existed for the impact CIS wanted to create for these students. Some believed it was preventing kids from dropping out of school; others thought it was improving young people’s behavior and confidence; still others believed it was promoting graduation and college.

For guidance here, the national leaders turned to CIS’s mission statement: “to champion the connection of needed community resources with schools to help young people successfully learn, stay in school, and prepare for life.” They clarified that their primary goal was to reduce students’ dropout rates. Improvements in behavior, academic performance, and grade progression would serve as early indicators that they were making progress against this end goal but would not constitute success in and of themselves.

How Will CIS Create Impact?

The options for how CIS would create impact – the network’s theory of change – were even more numerous. Over the years, local affiliates had adapted skillfully to meet the unique conditions present in the communities they served. This had given rise to varied program offerings. Some local affiliates provided mentoring and tutoring programs that helped kids stay in school. Others offered basic health and dental services. Still others helped students through counseling.

Given that each of these activities has the potential to help reduce dropout rates, defining a single “recipe” for achieving impact seemed impossible. The national leaders also knew that some variation was absolutely necessary to meet local communities’ needs, but they wondered how much was too much. The trick would be to find the core level of consistency necessary to create a cohesive network.

The project team tried to define this baseline by looking for common threads among the local affiliates’ program offerings, to no avail. When they stepped back from the specific programs, however, they began to gain traction. “CIS doesn’t offer products,” Milliken observed. “It is a process. We go into communities and convene the leaders who want to help kids. Then, we assess the needs of the community to see where the gaps are. And, we use our ‘five basics’ to fill those gaps.”

Milliken’s statement was a breakthrough. CIS’s means of creating impact was not a series of program offerings, but rather the process by which it entered a community and created partnerships to meet the needs of youth. As long as each local affiliate worked towards the same goal, understood its community’s needs, and formed the right partnerships, programmatic variations would be beneficial, not problematic.

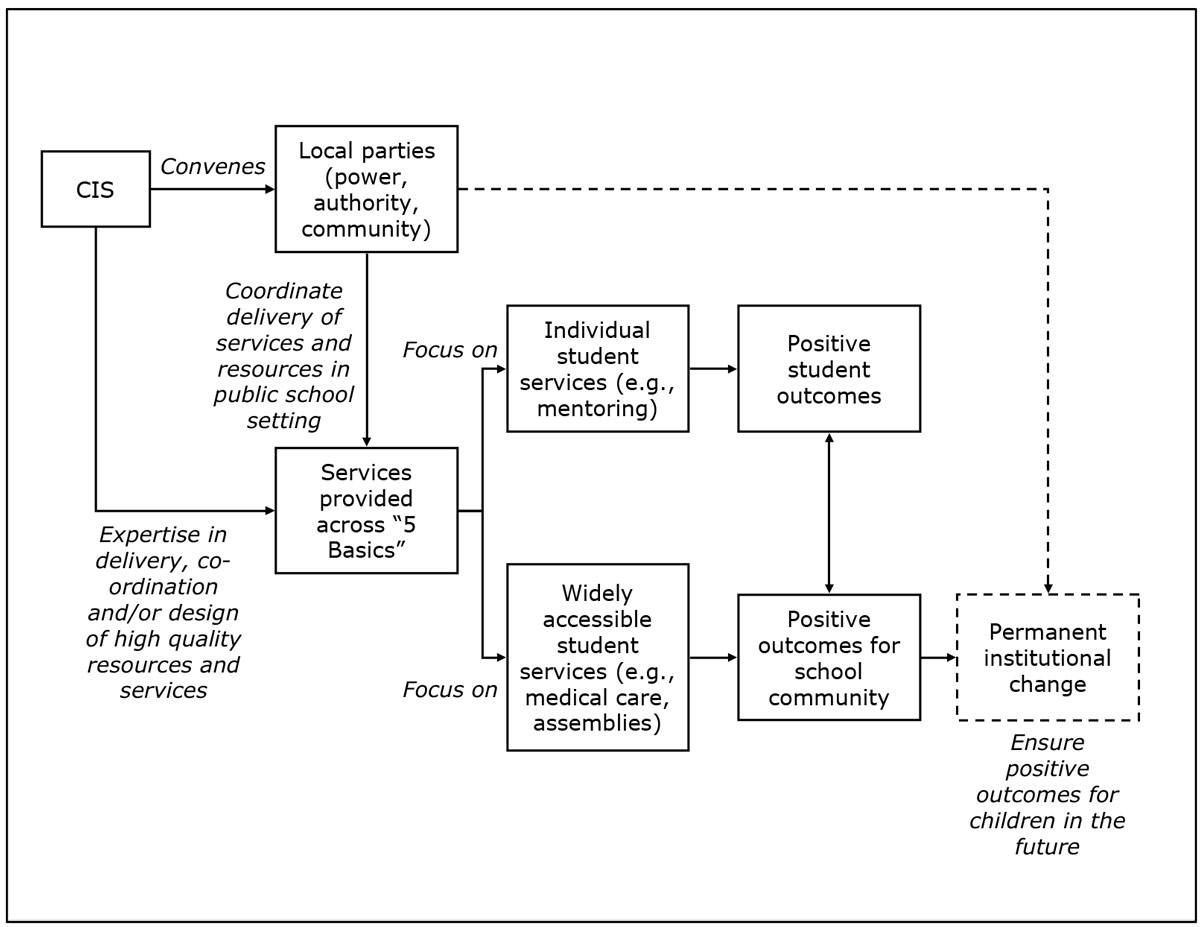

Exhibit A depicts the resulting theory of change for CIS. Importantly, the model includes not only direct provision of services, but also coordination of other resources in the community. Involving local constituencies such as parents, school system leaders, local legislators, and key business and community leaders was critical for achieving CIS’s long-term goal of permanent institutional change.

Exhibit A: CIS’s goals and theory of change

With the model drafted, the next step was to seek feedback from the state directors and selected local directors. Many comments were positive. As one director remarked, “I can’t believe how well [this captures] CIS and what we’re all about. We’ve needed a way to explain this, and this really gets at the core of what we do.”

However, a few expressed concern that the model didn’t capture everything. For example, CIS had developed some supplemental programs, such as learning centers called “Academies” that were separate from the schools. The more the group talked, though, the clearer it became that the model should represent the core – not the entirety – of CIS. Each CIS site had to have the core elements in order to be CIS; Academies were a strategy to sustain this core.

The board steering committee members of the project team played a crucial role during this phase of the project. Because the committee consisted of both new and long-tenured members and mirrored the diversity of CIS’s national board, it was able to represent the full board’s interests as the team clarified CIS’s goals and theory of change. And when the time came to secure the network’s commitment to the plan, the steering committee’s involvement in the planning process served as a powerful endorsement.

Redefining the Roles of Each Constituency

With a clear vision of the impact it wanted to achieve for youth and a unified theory of change, CIS next needed to determine the role each part of the network would need to play. Roles had changed very little over the past decade, even though CIS had grown considerably:

- The local affiliates (200 in total) managed programs in more than 3,000 schools. They assessed the needs of the youth in their communities and developed local partnerships and programs to meet those needs.

- State offices existed in states with a high concentration of local affiliates. In 2004, there were 14 state offices covering nearly half of the states where CIS had a presence. Their ability to support local affiliates varied, with some state offices providing for nearly all of their local’s needs and others requiring their locals to deal directly with National for select services.

- National was responsible for maintaining network standards and meeting local affiliate needs, such as training, technical assistance, outcomes tracking, public relations and marketing, fundraising, and partnership development, either directly or through the state offices. All together, National offered more than 50 different services to the network.

The static nature of these roles and the high degree of overlap between National and the state offices were sure signals that taking CIS’s performance to the next level would require some reshuffling. To increase the odds that the value of the network as a whole would be greater than the sum of its parts, CIS needed roles that were clear, practical, and comprehensive without being redundant.

The national leaders knew that local affiliates’ satisfaction with National was uncomfortably low. Some local affiliates had complained about not getting what they needed, and others were frustrated about having to submit outcomes when they didn’t feel they got much in return. The sheer breadth of National’s service offering was a possible source of the problem. One board member captured the sentiment: “National has a tendency to run an inch deep and a mile wide. We need to deepen what we know, and not spread ourselves too thin by trying too many things at once.”

To focus its efforts, National required more information about what the network truly needed it to provide. Which of National’s services were most important? Which services were the local affiliates and/or state offices in better position to provide? Realizing that the best source of information about what the network needed would be the network itself, the project team decided to survey the network.

Understanding the Local Affiliates'

Before reaching out to the entire network, the project team wanted to develop a better sense of the critical issues. Interviews with 10 local and state CIS directors revealed mixed opinions about National’s performance. Some directors gave National high marks. One local director said, “I’ve worked in social services for 10 years and have never come across a network that puts forth so much effort so that the operational sites can be successful – it’s refreshing!” Another said, “When called upon, they are extremely helpful.”

Other directors were far less satisfied. A local director, who had been running an affiliate for 25 years, believed that her state-supported local affiliate no longer needed National. “It’s like we had parents and they abandoned us, then they came back when we were teenagers and expected to have a say. We’ve got state parents now and don’t need National.”

The follow-on network-wide survey provided a means for understanding what was driving the divergent levels of satisfaction and which of National’s services the local affiliates valued most. More than half of the 200 local directors submitted survey responses, an indication in itself that they were eager for change.

A question asking the directors to rate the importance of each of National’s 50-plus services hinted at how National had gotten into its current “inch-deep-and-milewide” predicament. The directors ranked more than 90 percent of the services as valuable or extremely valuable.

Asking the directors to prioritize their top three services was more informative. A strong majority of the directors (nearly 70 percent) named brand-building activities. National fundraising (60 percent) and forging partnerships (36 percent) rounded out the top three. These services naturally fell into National’s realm, as they were difficult to do at a local level. One local director explained, “CIS National should champion CIS nationally via marketing, public relations and lobbying for ‘big bucks’ from national corporations and Congress. We can actually do the rest via our state or local affiliates.” The national leaders were surprised that the three services were so much more important than the others and that such a large percentage of the directors agreed on these priorities.

The survey responses weren’t completely uniform, however. Some directors noted other services, such as training, as priorities. Looking for common characteristics in this minority group, the project team realized they were on to one of the major reasons behind the divergent levels of satisfaction. The group was comprised primarily of directors from the younger local affiliates – the affiliates that relied most heavily on National for basic operational needs.

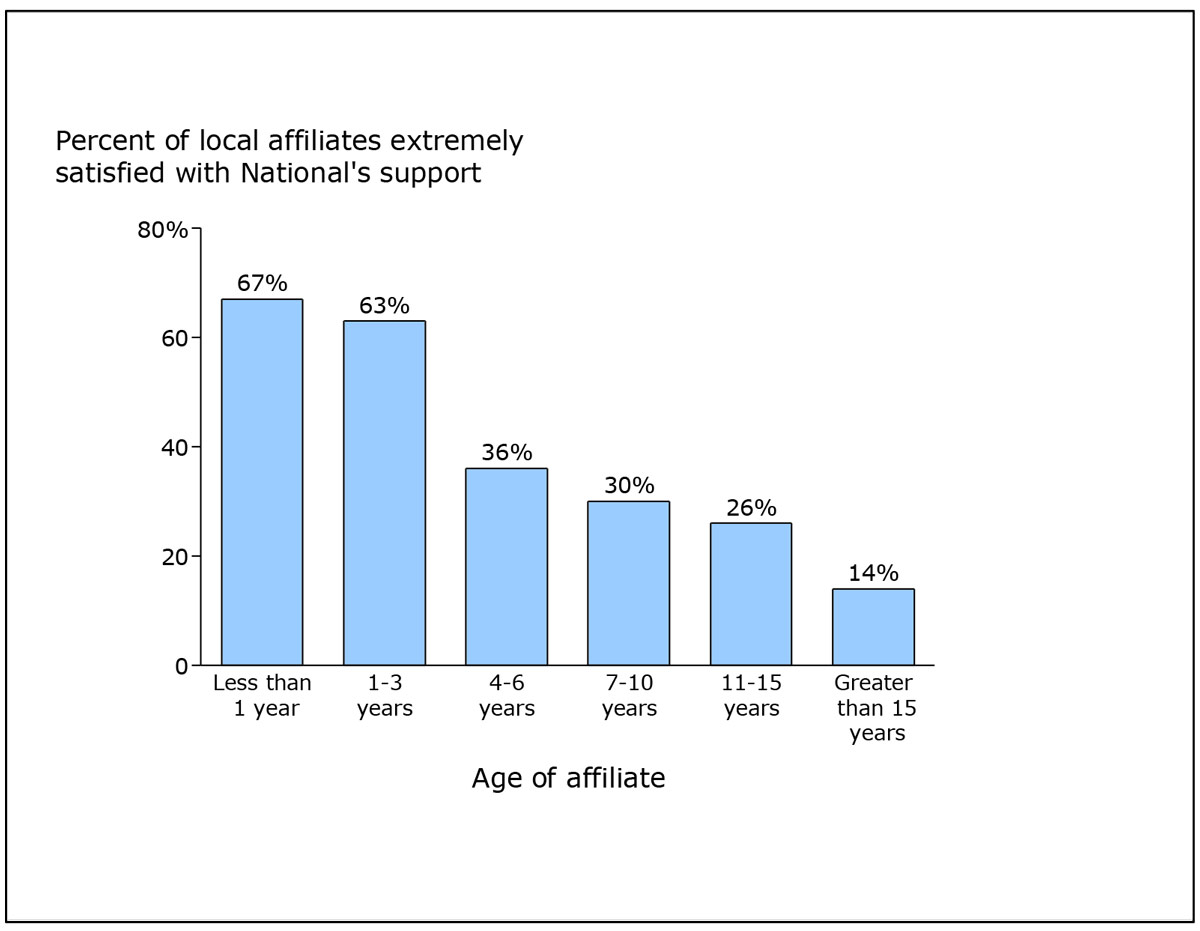

The national office had been doing a better job of serving the needs of newer affiliates. In fact, grouping the answers from a survey question about satisfaction with National by age of affiliate revealed a compelling picture. The older an affiliate was, generally speaking the less satisfied it was with National’s support. (See Exhibit B.)

Exhibit B: Older local affiliates were less satisfied with National’s support

To dig deeper into why satisfaction was so much lower for older affiliates, the project team analyzed how the national office staff members were spending their time. Was there a mismatch between what was important to the network and what national staff were paying most attention to? The data confirmed their suspicions. National staff were spending less than a quarter of their time on the network’s top three priorities.

A national staff member provided an explanation for this disconnect when she explained that it seemed the local affiliates needed so much that it was hard to know what to prioritize. “I feel like we are always putting out fires. A new local might call and need technical assistance right away because they can’t figure out how to track their youth, or a state office has an urgent need for Milliken to speak at an event. I never have time to take a step back and really think about what is most important or how we should plan for the future.” In the absence of clear priorities, services that were urgent and tangible (like those required to get new affiliates up and running) were getting the most attention. In contrast, externallyfacing activities (like brand building) were getting crowded out.

It was becoming clear that National needed to have a more externally-facing role, focusing on activities that benefited the network as a whole. It needed to increase its efforts on brand building, national fundraising, and national partnerships. But what about the other services the local affiliates (especially the newer ones) needed?

The state offices represented a possible solution. A high degree of overlap already existed between the services National and the state offices were providing to the locals. Perhaps there was an opportunity to transfer some of National’s current operationally-oriented services to the states. To begin to explore this possibility, the project team put aside the practical limitation of having state offices in only half the states in which CIS had operations. If research showed that the idea had promise they’d address this complicating factor.

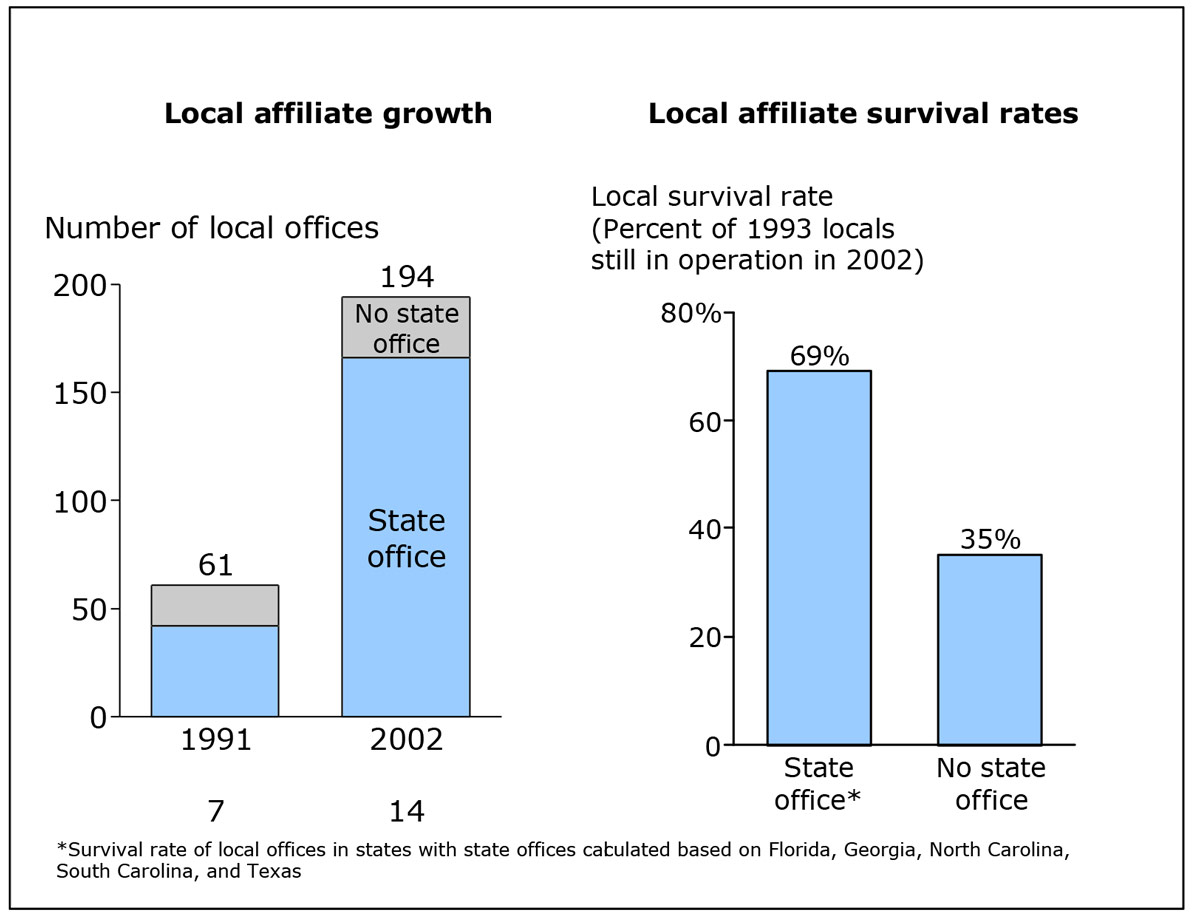

Data provided strong incentive for enhancing the role of the state offices. Since 1991, over 90 percent of local affiliate growth had occurred in state-office states. Additionally, locals in these states had nearly double the survival rate of the locals in states without state offices. (See Exhibit C).

Interviews with state directors also supported devolution. State directors rated their offices as best suited to serve certain operational needs such as training, technical assistance, launching new affiliates, and data collection, because they were more familiar with local needs and communities than National.

Exhibit C: State-office states were conducive to growth and survival

Reviewing the network-wide survey data, the project team found signs of receptivity to the idea. One question had asked the local directors about National’s role in supporting state offices. Nearly 70 percent had said it was most important for National to replicate and support state offices. And when the directors from states without state offices had been asked if they believed they would benefit by having a state office, 74 percent thought they would function more effectively, 63 percent thought they would have greater impact, and 48 percent thought they would be more stable.

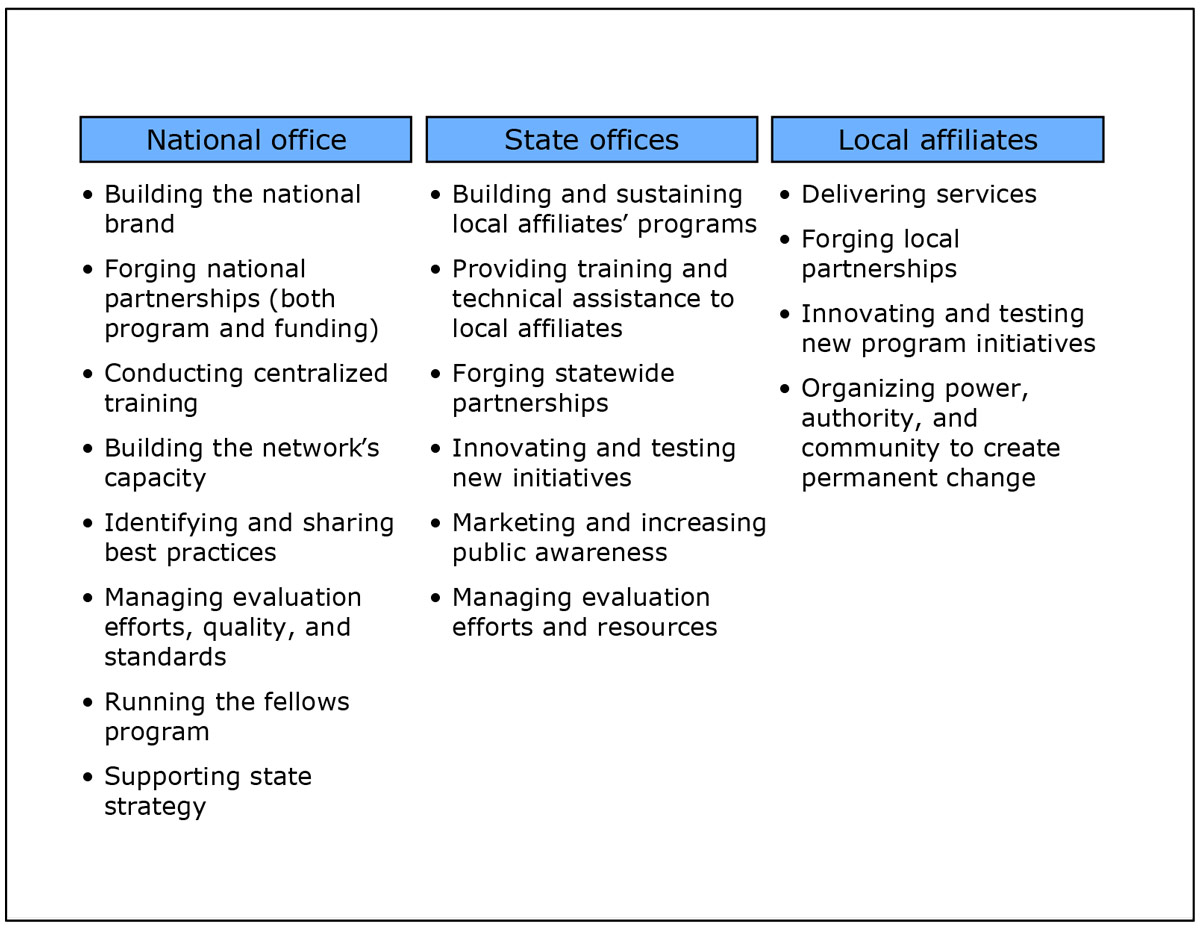

Altogether, the data and network feedback suggested that National should concentrate more on state office success. Instead of supporting every local affiliate in the network, it would work through the state offices. In CIS states that didn’t yet have state offices, National would work to establish them. The emerging roles for National, the state offices, and the local affiliates were designed to maximize each party’s contribution. As Exhibit D shows, they complemented each other and no longer overlapped.

Exhibit D: Emerging roles for the national, state, and local affiliates

Aligning the Organization with the New Strategy

With a clear strategy and newly defined roles, it was time to identify the organizational changes necessary for the plan to succeed. One of the major sticking points was that National currently wasn’t organized to support the new strategy in an effective way. While the plan called for National to concentrate on external activities on behalf of the network and to support the state offices, it was set up to do a little bit of everything to support local affiliates. Aligning National to the strategy would require modifications to the senior management team, staff, and board.

Rethinking National's Senior Management

The first critical decision was about CIS’s leadership. Bill Milliken is a charismatic leader and a force in youth advocacy. He had been president of CIS since he founded it in 1977, and he questioned whether he was still the right person to lead this next phase of CIS’s existence. He believed CIS needed to sustain itself past his direct involvement and was concerned by the lack of planning for his succession. In addition, Milliken’s work motivating communities, donors, and political leaders could be a full-time job in itself, even without his other responsibilities as president.

Dan Cardinali had been CIS’s executive vice president for three years. He had earned the respect of the local affiliates and state offices, had significant experience in nonprofit management, and enjoyed an excellent working relationship with Milliken. Milliken and the board believed that Cardinali had the potential to lead CIS, provided the division of responsibilities between Cardinali and Milliken was clear.

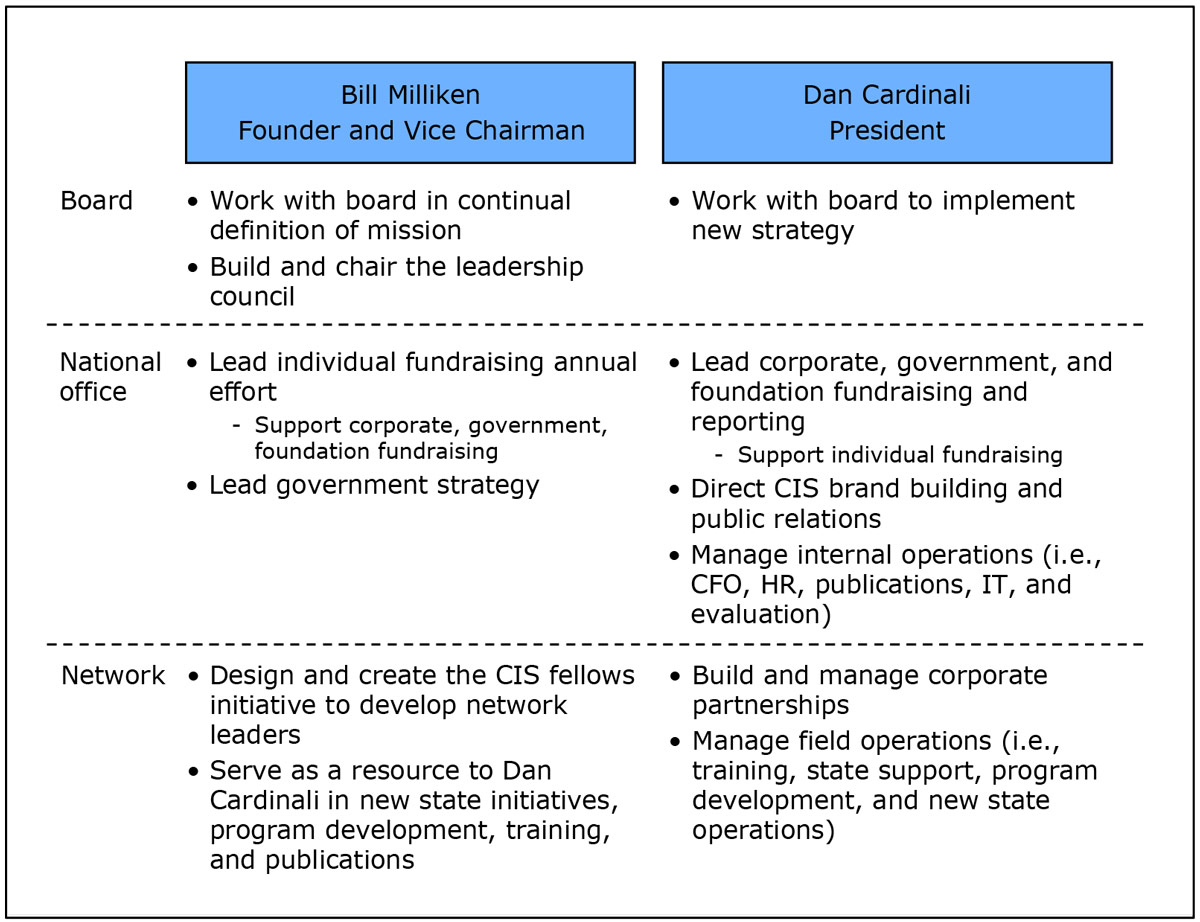

The decision was sealed. Cardinali would take on the title of “President,” and would be responsible for the management and operations of the CIS national office. Milliken’s new title would be “Founder and Vice Chairman,” with his responsibilities focused on federal fundraising and advocacy and large individual gift fundraising. Given Milliken’s commitment to having CIS endure, he would also work to establish a cadre of CIS leaders called “Fellows.” (See Exhibit E for more detail on the division of responsibilities.)

Both Milliken and Cardinali were excited about their new roles. The shift went into effect before the strategic planning plan was complete, serving as another signal to the network that Milliken and Cardinali were committed to real change and that this strategic plan would be different from other attempts.

Exhibit E: The new division of responsibilities between Milliken and Cardinali

The rest of the management team also required some modification. The initial temptation was to start with the current management team members, identify what individuals would be good at and enjoy, and then modify their positions. The magnitude of National’s role shift, however, suggested that this approach would not suffice; the risk of missing certain positions or responsibilities, and of overlooking the skills and attributes needed for those positions, would be too great. The project team would need to look first at the positions and capabilities that matched the new strategy. Only when those were clear would they consider specific individuals.

The management of CIS National included a vice president of the field, a chief financial officer, a vice president of research, and a vice president of communications. Given the new strategy, each of these roles needed strengthening. All members of the senior management team now would report directly to President Cardinali. Additionally, the project team updated the job descriptions and specifications to reflect the increased demands on these positions. They also added a director of development, in line with National’s increased focus on fundraising.

In looking at the skills and attributes needed for each of the five positions, Milliken and Cardinali realized that only two of the current employees met the specifications. CIS would need to make three external hires.

Repositioning The National Staff

Aligning National with the new strategy would take more than the management team changes; the entire staff needed to adjust. Currently each national staff member was responsible for specific services, so a local affiliate that needed both training and data collection assistance would have to contact two different people. This arrangement didn’t seem to be working, even before factoring in the major change from local affiliate to state office support. The network survey had revealed that 25 percent of the local affiliates that worked directly with National didn’t even know whom to contact for the services they needed.

This feedback pointed to a more customer-focused approach. Instead of having service-specific staff, each national staff member would be in charge of serving all the support needs of a group of state offices. This configuration not only would reduce confusion, but it also had the potential to make the national staff more accountable for the success of the state offices they served.

Furthermore, the state offices (like the local affiliates) had varying degrees of maturity and success, and therefore had different needs. A new state office like Arizona might require guidance in opening and training new local affiliates, whereas a mature, successful state office like Georgia might need help in attaining national exposure and federal funding. To better serve the varied needs of the state offices, the project team grouped them into three categories according to stage of development: long-standing success; poised for success; just getting going. National staff would tailor their services to each category’s needs.

Reorganizing the National Board

The CIS board included many well-known national leaders who were eager to contribute but often didn’t know how. The extensive involvement of board members throughout the planning process had demonstrated how valuable a resource the board could be. The national leadership would need to engage them more effectively on an ongoing basis.

In interviews with board members, the project team consistently heard that the board was not reaching its full potential. One member said, “I feel utterly useless. I have all of this expertise and experience, and it’s wasted...We spend meetings talking about good ideas, and then nothing happens – no one does anything about it.”

The board needed to be reenergized and focused on the new strategic objectives. Because several board members had been active participants throughout the planning process, the board truly owned the new strategy. This was critical since they would play a pivotal role in making sure that CIS adhered to its strategic plan. With National now focused on brand building, national fundraising, and national partnerships, the national board also would be responsible for these objectives.

One option for reinvigorating the board was to create committees. Some board members were skeptical of this approach, however, given that past experience with committees had gone nowhere. Diagnosing the past failures revealed three problematic design elements: the committees hadn’t had leaders; they weren’t designed to tackle a specific issues or tasks, but rather lasted indefinitely; and they didn’t have contact with the national management team beyond the president.

As a complement to the more standard executive, governance, and nominating committees, the board decided to form task forces designed around specific agendas. Each task force would operate only until it had achieved its specific assignment. Additionally, the task forces would have appointed leaders and map to a national staff person, to improve the odds that their recommendations would be implemented. For example, the marketing task force would work with the vice president of communications, who could help put in place the board’s suggestions. Furthermore, if the vice president of communications needed a board member’s help on a marketing issue, he or she could contact the task-force leader directly instead of having to work through Cardinali.

Making Change and Moving Forward

The goal of developing a new business plan had been to propel CIS to the next level. As the organization emerged from the planning process in July 2004, that goal seemed possible. CIS had established a clear statement of network goals and roles that was understood and endorsed by the network, national management, and the board. The responsibilities of the two senior leaders had been adjusted, the national staff had been reorganized, and the national board structure had been modified in line with the new plan. Importantly, the board had approved the threeyear financial objectives outlined in the business plan.

As of March 2005, CIS was already making strong progress on many dimensions. National had:

- Hired a chief financial officer and a vice president of communications;

- Launched a national brand-building campaign;

- Established two new board task forces around key initiatives;

- Achieved 100 percent affiliate participation in year-end data reporting;

- Secured several million dollars in new foundation and federal funding.