Summary

From its 1958 origins as the first Girls Club in Northern California, Girls Incorporated of Alameda County has expanded to offer girls a rich array of programming at 45 locations in the San Francisco Bay Area’s East Bay. Individual giving has propelled growth. Early growth was largely opportunistic, with the organization’s executive director seizing on opportunities to expand programmatically and regionally. But as the organization became larger, managing growth required her to plan growth more purposefully and to push down decision-making to an executive management team.

Organizational Snapshot

Organization: Girls Incorporated of Alameda County

Year founded: 1958

Headquarters: San Leandro, California

Mission: “To inspire all girls to be strong, smart, and bold.”

Program: Girls Incorporated of Alameda County challenges girls in the San Francisco Bay Area’s East Bay community to explore their potential, build careers, and expand their sense of what’s possible. Each year Girls Incorporated of Alameda County serves more than 7,000 girls ages 6 to 18 through a rich array of programs offered at over 45 schools and community sites. With names like WOW! (Watch Out World!) and Project SMART, these programs help girls in such areas as science and math, reading skills, careers, adolescent pregnancy prevention, child abuse counseling, health and fitness, economic literacy, technology training, teen leadership development, family counseling, and research and advocacy. Eighty-two percent of the girls served are from families of color, and most are from low-income families headed by single mothers.

Size: $2.9 million in revenue; 53 employees (as of 2003).

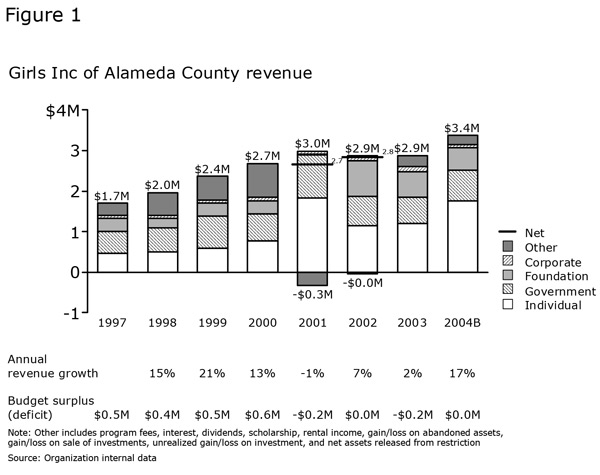

Revenue growth rate: Compound annual growth rate (1999-2003): 5 percent; highest annual growth rate (1999-2003): 21 percent in 1999.

Funding sources: Girls Incorporated of Alameda County’s budget comes from a mix of individual, foundation, and government funding. In 2003, 41 percent of funds came from individuals, 22 percent from government, 22 percent from foundations, 5 percent from corporations, and 10 percent from other sources. Individual funding increased to a 52 percent share 2004, propelled by an anonymous donor who provided 28 percent of the organization’s funding.

Organizational structure: Girls Incorporated of Alameda County is an affiliate of Girls Inc., formerly known as Girls Clubs of America. As an affiliate, the organization gains access to a core set of program models. The national organization evaluates these programs, but the local organization is also able to create programs specific to its local area. The national office provides management and program training, fundraising guidance, national advocacy and lobbying, and access to other affiliates working toward similar goals.

Leadership: Pat Loomes, executive director for 26 years; Judy Glenn, associate director, who has been with the organization for 25 years.

More information: www.girlsinc-alameda.org

Key Milestones

- 1958: Started as the first Girls Club in Northern California

- 1960: Opened its first office

- 1973: Established the Pheonix Program, the basis for its current program

- Early 1980s: Successfully lobbied the United Way to increase its funding for girls

- 1984: Conducted its first true strategic planning session

- 1994: Expanded into Oakland

- 1990: Changed its name to Girls Incorporated of San Leandro

- 1994 Changed its name to Girls Incorporated of Alameda County

- 1997: Filled out its service offerings, developing a comprehensive continuum of programs to serve girls as they grow older

Growth Story

Girls Incorporated of Alameda County started in 1958 as the first Girls Club in Northern California. It opened its first office in 1960, serving 20 girls after school in a small house owned by the San Francisco Bay Area city of San Leandro. In 1973, the organization established a model called the Phoenix Program, from which the current program evolved. The program focused on career development, recreation and education, and counseling.

“For years, we kept that basic model and grew pieces of that,” says Pat Loomes, executive director. The organization added programs to treat child victims of sexual abuse and to prevent teenage pregnancy. “Not only were we going to juvenile halls, but we were going into schools,” says Loomes. “We were leaving the notion behind early on of simply having girls coming to us.”

“We didn’t have a clue initially in those early days of where we were going, but we were going,” says Associate Director Judy Glenn. “And sometimes we’d end up saying, ‘How’d we end up with that?’ It wasn’t always thoughtful in our initial growth, but there was an entrepreneurial spirit … I think Pat’s a risk taker.”

Girls Incorporated of Alameda County received a major boost in the early 1980s, when the organization joined forces with other girls’ organizations and successfully lobbied the local United Way to balance out its boy-centered funding and dramatically increase its funding for girls. “We made gutsy moves — it was exciting because we didn’t know better, about being the underdog. Everyone would always talk about the Boys Club. They were bigger, they had the facilities, and all the big men in town were on the board at the Boys Club.”

With a steady stream of opportunities to reach more girls, management spent little time planning for growth. “Any little bit of money and we were off,” says Loomes. “There is a part that feels like the work is never done; the needs of girls are really significant and we’re not serving every girl. So it’s vast in terms of what we could do. It’s exhilarating, but hard.”

The national office only added to the growth-oriented atmosphere. “National is very small, much smaller than most other national organizations,” says Loomes. “So they have a desire, a need, to grow — in large part to show numbers for funders.” And the board was gunning for growth as well. “We couldn’t wait to be a million-dollar agency,” Loomes recalls. “It’s silly, you don’t even know why you want that, but it would get the board charged.”

Girls Incorporated of Alameda County had its first true strategic planning session in 1984. The organization decided in 1994 to expand from San Leandro into Oakland, a bigger city with bigger problems. “There’s enormous impact because of poverty, and the school districts have serious problems,” says Loomes. “If you can show positive results in Oakland, people take their hat off to you.”

In 1990, Girls Clubs of America changed its name to Girls Incorporated, and the San Leandro affiliate changed its name at the same time. In 1994 it further changed its name to Girls Incorporated of Alameda County to better reflect its service area throughout the wider East Bay area. The change of name and the move into Oakland brought serious funding from more wealthy areas like Berkeley and San Francisco. “We knew we’d get a new donor base, and that we’d be taken more seriously,” says Loomes. But the move brought the organization into contact with fierce local politics, which Loomes didn’t want to be a part of. “We chose to have a physical presence [the organization is currently building a new site in Oakland], but not to be at the table. We saw that you could go in, do quality services, and be recognized for that.”

In 1997, after learning that many girls dropped out of the program in middle school, management and the board decided to concentrate on increasing the depth and breadth of its services. They teamed up with Fern Tiger Associates in 1998 to create a strategic plan calling for the organization to increase the intensity of its service offerings and to create a continuum of services that flow logically as girls grow older. For example, GirlStart is a “bookend” at the beginning of the continuum and Eureka is a “bookend” at the end. “All numbers showed that these types of services are what work,” says Retha Howard, chief operating officer. “If you really want to be life changing, you need to look at the entire life of an individual girl and see where we should play. As a result, the programs are now very much threaded together… We decided on an intensive approach, and what that means is you don’t grow to as many sites and you don’t grow as quickly.”

Loomes is concerned about maintaining program quality as the organization grows. “Are we ready to grow and keep the quality?” she asks. “Now we’re opening our third site for the GirlStart program, and I’m still worried we’re not ready. It’s one thing to be running one little program at a site. It’s another thing to take it to three or four.” This concern was part of the organization’s motivation to develop a business plan in 2003, calling for infrastructure investments. “We realized we needed infrastructure to support growth, says Loomes. “Before, we had been focused on programs.”

Configuration

Girls Incorporated of Alameda County is an affiliate of New York-based Girls Incorporated. The national organization provides only a small amount of money to pilot new programs, and would not support a local affiliate financially if the affiliate developed a deficit. The local affiliate receives support from the national organization mainly in the form of consulting for fundraising and program evaluation, especially if national is interested in rolling out programs that have been developed at the local level. The national office also conducts national advocacy work and lobbying for girls.

Girls Incorporated of Alameda County sees mainly positives from its affiliation with a national organization. “They’ve given me more money than I’ve given them,” says Loomes. “They aren’t onerous in what they demand. They were very helpful in supporting our growth efforts, not only financially but from the management perspective in terms of training, program training, management training, and so on.”

Capital

Girls Incorporated of Alameda County relies on individual funders to support its growth. Generally, the organization has tried to maintain a mix of 30 percent foundations, 30 percent individuals, 30 percent government, and 10 percent from such sources as program fees, rental income, and investments. (See Figure 1.)

Maintaining a goal of 30 percent of funding from individuals, however, has been difficult following the receipt of a $10 million donation from an anonymous donor whom Girls Incorporated of Alameda County has cultivated over many years. He structured the donation as a “challenge grant” to be paid over five years, and has been instrumental in recruiting his wealthy friends to form an advisory board. The gift is meant to go solely to fund program-related growth, although occasionally the donor will let some of the money go to organization building if the organization can fund certain programs other ways. This anonymous donor accounted for 28 percent of the 2004 budget, boosting individual funding to 52 percent of total funds. Girls Incorporated of Alameda County is actively planning to replace the funding when it runs out.

The organization manages its mix of funding sources much like a portfolio of stocks. If it expects an economic downturn, it will try to increase individual giving to subsidize what it anticipates will be a decline in foundation giving, which is often directly tied to the performance of the stock market. If it anticipates that government sources will dry up, it pushes harder on foundation funding. The organization sees more foundation funding on the horizon, even though it finds that foundation money comes with numerous demands attached.

“We were pretty much a leader in knowing that in order to grow and sustain this organization, we had to sustain individual donors,” says Loomes of the organization’s financial focus. The money from individuals has its advantages. “We have had unrestricted money and that allowed us to do what we needed to do. You can set the priorities for the first time, and that’s exciting.”

Up until 1980, Girls Incorporated of Alameda County received up to 90 percent of its funding from the government. The organization was pushed toward individual donors when government money dried up during the Reagan administration. Now government funds provide a base, but they have never been sturdy enough to rely on for growth.

Loomes thinks the transition to individual donors, while not planned, turned out to help the organization in the long run. “There’s a way that you have to talk to individual donors that is different from the government,” she says. “You tell the government, ‘We told you we’d see 800 kids and we saw 800 kids,’ and they’re happy if you’ve done that. Individual donors are not. Individual donors are more engaged — they want to see the program, they want to talk to the kids.” Additionally, the organization currently has a $2 million endowment, which it hopes to grow through planned giving programs.

Growth has brought with it the need to increase staffing to support the relationships, donor education, and events that individual donors require. The organization has six staffers devoted to managing individual and foundation donors and to plan such events as the annual Women of Taste gala, which raises $180,000 per year.

Capabilities

2003 was a busy year for Girls Incorporated of Alameda County. The organization put in place a plan to decentralize decision-making, hired an executive management team, and drafted a succession plan for the current leadership.

The impetus to create organizational change grew from a strategic plan that started as a pro bono consulting project with an alumni group from Harvard Business School. (A professional services firm eventually took over.) “We identified a need to push decision-making out and down,” says Brooke Schwartz, a board member and leader of the HBS consulting group. “[Loomes and Glenn] had all the decision-making methodology in their own brains, so we felt that as the organization grew, the decision-making should be more dispersed, which would be empowering to people here. This is a key growth factor for any organization as you go from small to a certain level.” The organization also needed a succession plan, “for when or if Pat and Judy ever step down,” says Schwartz.

Executive Director Pat Loomes has been in her position for 26 years. Associate Director Judy Glenn worked her way up through the organization over the last 25 years. Traditionally, the organization has staffed up as new programs have grown. But recently it began adding a management layer to oversee programs and internal operations, as well as to deal with the increasing complexity of running a large organization. “At around 15 or 16 [staff] you start having to think about personnel policies, you need a lawyer on the board, and so on,” says Loomes. “Around this point you can almost become bureaucratic. And then once we hit 50, we came under a whole set of laws that are stringent and expensive. Now you have to have policies. There are a certain amount of things that take the fun out of it.”

The executive team now includes Chief Operating Officer Retha Howard, a Wharton MBA and former consultant, and Chief Development Officer Janelle Cavanaugh, a MSW from UC Berkeley who formerly led major gifts at the United Way.

The organization tried a lot of new information technology systems before settling on its current setup. Staff who joined the organization with the new executive team have brought with them a desire for updated systems, such as the fundraising software called Raiser’s Edge. Other updated systems will follow soon. “You figure out the right balance by trial and error,” says Loomes. “The new system is quite layered and is just coming into play. We had a new system last July, and now we have another new system. As we grow, it seems we keep constantly having to reorganize, because what you do doesn’t work.”

Staffing issues are one of the biggest challenges to the organization. “The hard thing is the organization is always in flux when you are growing, and [staff] don’t quite understand what you are doing,” says Loomes. “Staff like and don’t like the growth — they don’t like the confusion, but they do like the opportunities that the growth creates.”

“I lose 80 percent of my program staff every year — many of whom are young part-time workers — so we’re training a new group every year,” she says. “And their supervisors are young also.” The organization therefore isn’t able to recognize greater efficiency because workers leave as soon as they move up the experience curve. “The issues of the girls we work with are so much more complex now,” she says. “Our staff has to see very, very hard things, and they are blown away by what comes at them from children. They’re not therapists, they are young youth workers. So as an organization we have to think, ‘What do we need to do to help our staff?’ This is an issue in the youth development field, and we’ve got address it.”

The organization now wants to create better career paths for its staff. “I think it’s a different workforce than when I first came into it,” says Loomes. “When we grew up, you did it because it was political work — there was some issue or cause like feminism or civil rights that was driving you. Now folks do it because it’s a career path. As we grow, our staff want tracks, want to be trained for the next level, want to know what the next level will be.”

But a new performance review system initially encountered resistance from staffers. “People here want career paths, so you have to get them to understand the reason for performance reviews,” says Howard. “You sell the upside. At the end of the day, you want to retain the people you have and you want them to grow.”

Another organizational milestone for the organization has been the transition from a programming board to a fundraising board. “It has been changing steadily, and this is possibly where the growth part will be most difficult,” says Loomes. “We need to bring on more people to the board who have influence, who have the money. Now we have people who can give $500 to $1,000, but don’t have a lot of influence.” Loomes plans to add board members in the future who can be primarily money-raisers and ambassadors for the program, rather than overseeing day-to-day operational issues.

Key Insights

- Focusing on individual donors. The organization has been able to grow successfully by focusing on individuals to pull it through a major growth phase. This push has had some benefits, such as large unrestricted funds, but it has meant greater costs for staff to manage donors and events.

- Decentralizing decision-making. The organization knew that it needed to push down decision-making to an executive management team for the long-term sustainability of the organization. However, it has struggled to transition this theory of decentralization into reality. An external strategic plan and an infusion of new talent seems to have helped the process along.

- Bolstering systems. The infusion of professional talent into the organization has led to the creation of new systems and processes. The new chief development officer brought with her an eye for fundraising systems, which has led to a push to update technology. The new chief operating officer brought with her an eye for program alignment, which has led to the creation of a system for evaluating new program ideas and performance reviews.

- Creating career paths. As the organization has struggled with high turnover, it has seen the importance of creating clearly delineated career paths for lower-level staffers to follow. Rather than highlight the negative aspects of a new performance review system, the organization has framed the system as a way to better deliver career options.