Summary

Larkin Street Youth Services has grown its programming dramatically over the last decade, in direct response to the emerging needs of homeless youth. A visionary executive director fostered a client-centered culture of excellence that drove the growth. But sustaining success required the organization to develop the ability of the management team and board to help the executive director manage Larkin’s increasing scale.

Organizational Snapshot

Organization: Larkin Street Youth Services

Year founded: 1984

Headquarters: San Francisco, California

Mission: “To help homeless and runaway youth exit life on the street.”

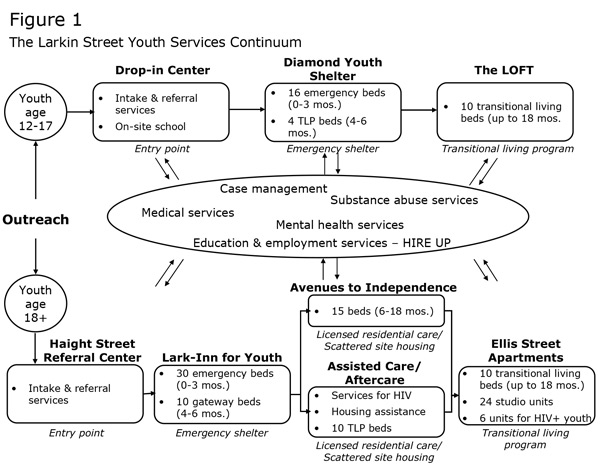

Program: With 17 programs operating out of eight San Francisco locations, Larkin Street Youth Services offers a comprehensive continuum of services designed to respond to homeless youth’s immediate, emergency needs, while providing the building blocks necessary for long-term stability and success. All services are aligned to work toward Larkin’s ultimate social goal: giving homeless youth the opportunity to exit life on the street for good. Point-of-entry and support services include street-level outreach; drop-in and referral centers; case management; medical, mental health, and substance abuse services; and a community arts program. Housing services consist of a youth shelter for kids ages 12 to 17; the Loft, a 10-bed transitional living facility for youth ages 15 to 17; and emergency housing for youth ages 18 to 23. HIV specialty services offer residential care, a medical clinic, and a program for youth living with HIV. Educational and employment services provide young people with job opportunities and career training; an on-site school where youth can take classes and pursue a GED; and a day-labor program. Larkin annually serves more than 2,000 youth and young adults ages 12 to 23. In 2003, over 80 percent of the young people who completed one of Larkin Street’s residential programs permanently exited street life.

Size: $8.3 million in revenue; 122 employees (as of 2003).

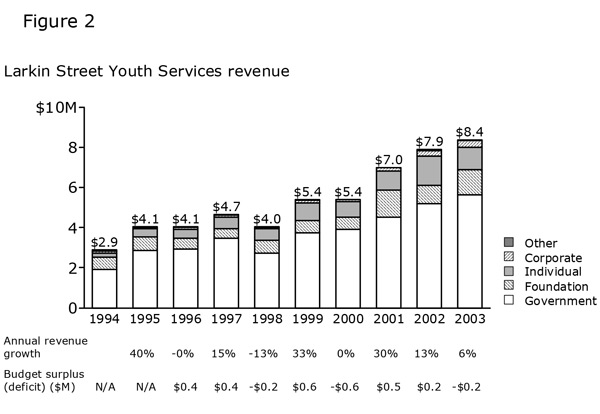

Revenue growth rate: Compound annual growth rate (1999-2003): 12 percent; Highest annual growth rate (1999-2003): 33 percent in 1999.

Funding sources: In 2003, 67 percent of Larkin’s funding was from the government, and of that about 55 percent was from local government, 39 percent was from the federal government, and the remaining 6 percent was from state government. Foundations and individuals were other major sources, providing 15 percent and 13 percent of total Larkin funding, respectively.

Organizational structure: Larkin Street Youth Services is a stand-alone 501(c)(3) organization with eight locations in the San Francisco Bay Area.

Leadership: Anne Stanton was executive director during the studied growth phase. Stanton left Larkin in late 2003 to become the program director for youth at the James Irvine Foundation. Genny Price is Larkin’s new executive director.

More information: www.larkinstreetyouth.org

Key Milestones

- 1984: Founded as a neighborhood effort to divert homeless and runaway youth from prostitution, drug dealing, and theft

- 1994: Expanded offering to better serve youth for whom family reunification was not a viable option; hired Anne Stanton as executive director

- 1995: Opened the Haight Street Referral Center; created a chief operating officer position

- 1996: Started Avenues to Independence transitional living program

- 1997: Opened the HIV Assisted Care Facility

- 1998: Started HIRE UP employment services and redesigned the HIV Aftercare Program, including a new HIV Specialty Clinic

- 2000: Opened the Lark-Inn for older youth

- 2001: Opened the Ellis Street Apartments for permanent housing

- 2003: Started LEASE transitional living program for emancipating foster youth

- 2004: Brought in Genny Price as the new executive director

Growth Story

Larkin Street Youth Services started in 1984 as a neighborhood effort to divert homeless and runaway youth from prostitution, drug dealing, and theft in the Tenderloin/Polk Gulch area of San Francisco. In its first year, it provided food, clothing, and a safe haven for 70 kids in a drop-in center.

In its early days, Larkin was a grassroots organization without a plan for growth. “Larkin was very much a neighborhood organization,” says Phil Estes, a board member since 1993. “It grew in fits and starts. [Growth] was way more reactive than strategic. Given the ‘grassrootsy’ board, it was much more about day-to-day survival and opportunities in the community than growing for growth’s sake.”

During the first decade of its existence, Larkin ran a drop-in center on Larkin Street and offered outreach services. “We didn’t have any residential services at that point,” says Estes. “So it was a storefront. We were in the business of trying to get homeless and runaway youth off the street without a place to put them.”

Over the years, Larkin has served an increasing number of homeless youth in San Francisco, growing from 1,950 in 1997 to 2,143 in 2003. The youth that Larkin serves are diverse in terms of race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, and place of origin; but they share histories of physical or sexual abuse (82 percent), families unwilling or unable to care for them (73 percent), and suicidal thoughts or attempts (62 percent).

Street outreach and multiple points of entry into services are central to Larkin Street’s model of care. Since homeless young people are often unaware or wary of social services, Larkin Street conducts street outreach seven nights a week in the neighborhoods where homeless youth congregate. It then offers a range of services to get youth into housing, medical care, and employment.

After a decade of providing crisis intervention and basic care for homeless youth, the organization started a three-year mission clarification process. Anne Stanton came on as executive director in 1994 and added her vision to Larkin’s new strategy (she left the organization in late 2003). “Before I came, [Larkin] had done a good job of gaining a reputation of providing excellent point-of-entry services to the most fringe kids,” Stanton says.

Larkin’s new vision was dramatically greater in scope: develop a comprehensive continuum of services for the increasing numbers of youth ages 16 to 21 (over 70 percent of those served) for whom family reunification was not a viable option. In the coming years, Larkin designed, funded, implemented, and evaluated eight new programs to fill service gaps and help youth stabilize their lives, secure permanent housing, and achieve economic self-sufficiency.

Besides creating a more extensive continuum of services for the youth it served, Larkin chose to serve a wider age range of youth. This extension included what the organization called “overage youth” ages 18 to 23, based on the lack of services available for this age group (For an overview of the resulting range of Larkin’s services, see Figure 1.)

Strategic planning helped Larkin’s management realize that it wanted to grow. The needs of its population demanded it, government funding had expanded to support it, and an active and engaged board wanted it. “Part of what came out of mission clarification was a desire on the board’s part for Larkin to realize it can’t just be about point of entry anymore — that’s a Band-Aid,” she says. “I had a very clear sense for the solution. Housing was the cornerstone of what that solution looked like. We started with housing because it was such a critical need, and developed services around it. The bottom line was that you had to look at the long term for the kids. The only option was to rebuild a cocoon around their lives, and that implied a lot of growth — and that growth would be expensive given that we would be providing 24-hour residential care, not just drop-in services.”

During the growth phase, senior management was sensitive to maintaining the organization’s overall level of quality and consistency across different sites and programs. “There were definitely times when people were overwhelmed and didn’t think we could do another thing,” says Stanton. “But I think because the model was a continuum, you were relieving stressors from some people.” Individual staff who had been overwhelmed trying to deal with a wide range of problems among youth could now each focus on a narrower set of issues.

“One of the challenges as we built the programs was having a clear and consistent vision of how the programs were going to run,” she continues. “Because the programs were operating in different places throughout the city, we had to work hard to maintain a consistent culture — to not have islands, where each program site would just do what they wanted to do. It was clear when that was happening, and it wouldn’t go on for long. Integration was key to growth, especially given our continuum-based philosophy of care.”

“It was very exciting to go through those bursts,” says Denise Wells, chief operating officer, who joined the organization in 1995. Growth was contagious — people were excited.” Wells also recalls how important Stanton was as a motivating force. “Anne [Stanton] generated a passion. It was incredibly inspiring for the management team, and it flowed down to the staff.”

The organization is also closely aligned with outcomes data. Stanton had long valued data collection and analysis for program management, but was adamant that the evidence organizations collect be in the context of what the organization needs to operate effectively. “It’s more and more trying to find ways to set goals and objectives you can measure against,” she says. “For us, that was asking, ‘What do we believe are the basic indicators of whether a kid is successful?’ It became more and more clear to the staff about what we were trying to do after that.”

She believes data collection is less burdensome if it is strategic. “If you are true to your mission and you aren’t chasing funding, you’re able to craft whatever funding agreements you have to serve what you’re ultimately trying to do,” Stanton says. “If your funding is aligned with mission, your performance measurement is aligned.”

Data collection for government funders gives Larkin’s numbers added rigor. “The amount of accountability and documentation that is required for the city is pretty unbelievable,” Stanton says. “So [an organization has] built in systems if [it has to report to the city]. The key is how do you set up the systems and grants so they’re talking to each other.”

Larkin uses the data it collects to provide feedback to funders and to make adjustments to programs. “Having the capacity to do some organizational learning as you’re going — what’s working, what’s not — is useful,” Stanton says.

Configuration

Larkin Street Youth Services is a standalone 501(c)(3), with a board of directors that oversees the operation. Larkin’s senior staff and board carefully evaluated options for expanding to other cities and decided, at least for the time being, they would stay put. Their analysis showed that the unmet needs of homeless youth in the San Francisco Bay Area were many. Larkin also recognized that the communities of homeless youth had very different needs in different geographies that required specially tailored approaches. However, to expand their impact, Larkin has plans underway to advise organizations serving homeless and runaway youth in other cities about best practices and lessons learned from their work in San Francisco.

Capital

Larkin has relied extensively on government funding to support its growth, with government sources consistently accounting for two-thirds of Larkin’s revenue. The organization has worked hard to grow private funds in lock-step with its government dollars, purposefully maintaining revenue from non-government sources at least one-third of total revenues for the past 10 years.

When the organization began considering growth, the size of its funding needs necessitated a capital campaign. “When I came with my vision, there were people who pushed back around [adding overage youth], around moving into more comprehensive care, around the HIV and assisted care facility,” says Stanton. “The capital campaign and the other stuff we needed were frightening.” That capital campaign in 1994 to 1995 was integral to Larkin’s growth. “With the first capital campaign it became more clear as to what the board’s responsibility was, especially their role in fundraising,” she says.

Before Stanton arrived, the board was more events-focused. “They would be putting forth a huge amount of work for $30,000,” she says. “Not all the board was giving, and the gifts were around $200.”

“At the start, the board was really eclectic — a wacky collection of committed people,” says Estes. “Small business people, some downtown business people, stay-at-home moms, independently wealthy folks, and so on. As the organization evolved, the people who were more grassroots-oriented, who wanted to be involved with the program and kids, left. When you start talking about fund development, you see self-selection. We had darn few people who saw the changes of the board and still wanted to stay.”

The success of the 1994/1995 capital campaign, and of the subsequent growth, helped change that. “It’s a synergistic thing — the prouder [the board is] of what’s going on within the organization, the more they’ll put themselves out there for it.”

Stanton brought in an outside fundraising expert to increase the board’s fund development capacity even further. The fundraising expert helped the organization establish ways that board members could be involved in the fund development process beyond soliciting donations. Larkin board members now self-select into one or more of three roles — Advocates, Ambassadors, and Askers — depending on their personal preferences and capabilities. Advocates promote Larkin’s name in the community. Ambassadors identify potential donors and help assess their capacity to donate. And Askers make “the ask” to the people identified by the Advocates. Defining these more nuanced roles has allowed board members who are less comfortable asking people to donate to remain involved in the fund-development process.

Additionally, Larkin established two board committees to assist with key fundraising efforts. The Major Gifts Committee now helps the chief development officer and the executive director with the Major Gifts Campaign, and the Planned Giving Committee assists the chief development officer in developing and implementing the Planned Giving Campaign.

Larkin has a sophisticated and comprehensive accounting system. It matches revenue dollars to programs and allocates overhead across programs. The organization uses unrestricted funding for program design and development — using a pilot phase to demonstrate a new program’s effectiveness — and only launches a new program when the organization is assured there is full funding.

As the organization grew, the need for a financing strategy grew, as well. Eventually, Larkin would not add programs without having a sense beforehand of where the funds would come from. Usually, Larkin would plan for some mix of individual and government funding. “We had a certain set of rules for decision making,” says Estes. “Sometimes we went into [new projects] having the city, state, and federal piece buttoned down, but not having the unrestricted funding. But we were always confident that the amount that was going to be required from us would be doable.”

After 9 percent compound annual growth from 1994 to 1998, revenues grew at an annual rate of 12 percent from 1999 to 2003. As of 2003, Larkin’s revenue mix stood at 67 percent government, 15 percent foundation, 13 percent individual, and 4 percent corporate. Among these revenue sources, funding from individuals saw the highest compound annual growth rate from 1994 to 2003 (20 percent) followed by corporate (14 percent), government (13 percent), and foundation (9 percent). (See Figure 2 for a summary of financial growth.)

A key driver behind Larkin’s success in expanding individual giving has been increasing the average contribution size. Growth in individual funding has helped fuel unrestricted revenues, which have grown faster than restricted revenues, allowing Larkin to invest in building the organization’s infrastructure. Within government funding, city money has played an increasingly important role, rising from 36 percent of Larkin’s government revenue in 1994 to 55 percent in 2003.

Capabilities

In its early years, Larkin hired executive directors who came from the program side, but whose administrative skills may not have been as strong. When the board brought in Anne Stanton in 1994, it issued a strong mandate for change. But she faced an organization that was resistant to her vision. “The culture [before I came] was extreme,” she says. “Everyone had an opinion. It was an exceedingly consensus-driven culture. It was not professional at all. It was very grassroots. It was hard to tell who was a kid and who was a staff member. There was very little structure for programming or anything else.”

She felt the culture and operations needed to change in order to prepare the organization for growth. “It was a huge culture shift when I came in,” she says. “There was a clear sense that I was not the staff’s first choice, because it was very clear that my style was different [from theirs]. And though there was a bit of cleaning house, there was support from key staff, and the board had absolute confidence in me.”

Stanton says she came in with a preference for clear lines of decision making typical in more hierarchical organizations, but she was also driven to serve the mission. “The issue for me was always about the youth,” she says. “People who could not perform at the level [of the expectations we had] of the youth could not perform with Larkin. My view of professionalism is very centered around what I think the young people deserve.”

The culture of Larkin is built on the sense of optimism and high expectations that Stanton set. “When Anne [Stanton] had decided that a new initiative was important, ‘no’ wasn’t part of the vocabulary. She brought a ‘can do’ attitude to the organization,” says Wells. Stanton also thinks people are attracted to an organization in which they feel they are part of something dynamic. “You get quality people by paying them well and attracting them with the vision,” Stanton says. “They have to be inspired by what they’re coming into. You don’t put people in static positions.”

She realized that she had to work with much of the pre-existing talent within the organization. “You have to build an organization, to some degree, based on the people that are there,” she says. “For example, given the tenure and the skill level of the program director, he was an important ally in the process of transforming the organization.”

When Stanton started, she directed fundraising almost entirely by herself. “Anne [Stanton] was new and immersed herself in the work,” says Wells. “She was trying to put Larkin on the map. When I first came, Anne was immersed in everything. Her time was 50 percent program and 50 percent development.”

But Stanton’s role gradually changed, and she began building a management team to help her lead the organization. In 1995, Stanton added Denise Wells as chief operating officer and ceded such functions as finance, human resources, and facilities to her.

The organization has tried to add a development director several times, but this has been the most difficult hire to get right. It has been difficult to find a candidate who would be comfortable working alongside the executive director rather than calling all the shots. “We always tried to find somebody who had some development background and would fit into the hierarchy and the salaried staff,” says Estes. “I can remember six development people we had. And at the end of the day, none of them were a great fit. They all had backgrounds in development, but hadn’t developed their senior skills.”

Stanton wishes she had hired a senior evaluations and research director who could have freed up some of the time program managers devote to reporting outcomes, as well as more staff in the finance area. “Over the years I would say that we were less successful with building the administrative function in a way that consistently wasn’t too stretched,” she concedes. “It was too lean. For eight of the 10 years, I was development director and executive director. I think leadership around that administrative area would have built structure.”

“It’s critical to have a senior team that can do the same thing as you,” she adds. This strategy of hiring highly skilled managers was in response to a few hiring mistakes. “We made a couple of wrong hires, and so we went up a level.”

Stanton’s recent efforts to develop the staff and to expand the role of the board turned out to be wise investments, as in late 2003 Stanton left the organization to become the program director for youth at the James Irvine Foundation. The foundation had recently revamped its strategy, refocusing most of its grants on preparing low-income youth, ages 14 to 24, academically for post-secondary education, the workplace, and citizenship. It was looking for an experienced nonprofit leader to reach youth throughout the state. It was an unparalleled opportunity for Stanton, and the timing was right given that Larkin was as well positioned as an organization could be for a leadership change. Genny Price became Larkin’s new executive director in September of 2004.

Key Insights

- Growing with excellence. Stanton was able to take over an existing organization by relentlessly communicating a new vision of excellence. But to be successful, she had to rock the boat; she had to let go of some responsibility, transition some staff out, and bring in additional senior-level management.

- Creating a continuum of service. Larkin Street has pioneered an effective and comprehensive web of services for the full spectrum of youth in crisis. Dedication to innovating to meet homeless youth’s needs has made this continuum of services possible and has enabled Larkin to attract and retain high quality staff and funders. Looking ahead, a key challenge will be to maintain momentum and job satisfaction if and when the growth in programs slows down.

- Focusing the board. A division of labor has enabled Larkin to increase the board’s involvement in fund development. New board responsibilities allow members to self-select according to the role they want to play in fundraising. And added committees now work directly with the chief development officer.