Introduction

Organically-grown produce, eco-labeled wood and fish, Fair Trade coffee—all are products that producers and sellers voluntarily certify as developed in an environmentally and/or socially responsible way. After marching along for years as an army of one or two entities, voluntary certification programs have risen fivefold since 1992, in some cases prompting a national standard.[i]

Today, nearly 30 national and international bodies certify natural resource-based products or “green” manufacturing facilities. They give qualified producers their seal of approval and urge consumers to reward sustainable production in the marketplace. By creating common ground for conservation and commerce, these bodies are playing an increasingly important role in promoting market-based efforts to protect biodiversity. In the process, they are helping corporate wholesalers and retailers see that sustainable production, while often costlier than the alternative, can make good business sense.

Over the past two years, the Bridgespan Group, a Boston and San Francisco-based non-profit consultancy, has analyzed two major certification and eco-labeling programs—the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) and the Marine Stewardship Council (MSC)—in the course of client work for foundations in the United States and Europe. Recently, we supplemented this work with research into other certification programs, including Fair Trade coffee and organic agriculture. The objective was to sharpen our understanding of certification’s prospects: When does certification make sense? What distinguishes a plausible program from one that isn’t likely to have real impact? What steps can increase the odds that a certification program will succeed?

The subject of certification has received considerable attention from academics, scientists and others interested in issues such as biodiversity and sustainability. In adding our voice to the mix, we hope to provide a practical perspective that will help to inform both the efforts of organizations working on certification and the decisions of the foundations and other funders whose support is essential to helping those efforts take hold.

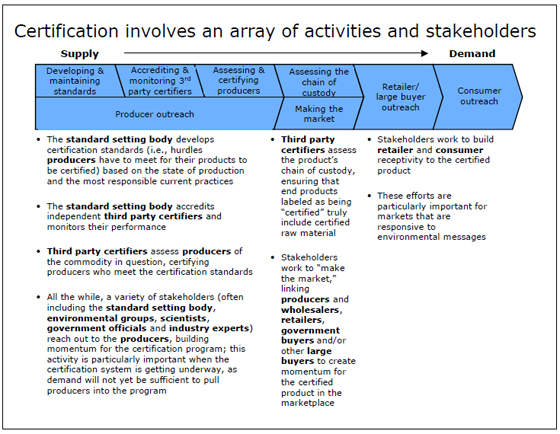

The gist of our findings: A certification program’s power to reform practices involves far more than setting standards. Making certification work demands persistent energy over time from stakeholders as differently motivated as environmentalists, producers, corporate buyers, government officials, scientists and standard-setting bodies. (See Figure 1: Certification process overview.) Our review uncovered a series of critical steps that effective certifiers are using to propel niche markets toward mainstream production and to turn sustainable practices into industry norms. These steps are:

- Meeting, not trying to create, a receptive market

- Pushing, not just setting, the certification standard

- Creating an attractive value proposition for producers

Figure 1: Certification process overview

|

Making certification work also requires external funding. Whether certification systems can ever be self-supporting isn’t clear; what is clear is that this isn’t a plausible short-to-medium term goal. There are no obvious revenue streams associated with the primary activities a standard-setting body must engage in: advising and training certifiers, providing oversight for assessments, and monitoring best practices to keep the standard up to date. For this reason, it is highly likely that they will require ongoing philanthropic support.

Meeting the Market

Setting a standard for sustainability in an unreceptive market is tantamount to putting a price on an invention that nobody understands. The contraption may arouse curiosity, but it is unlikely to take off. Eco-certification can encourage more sustainable, mainstream business practices, as we will see. But these efforts are more likely to succeed where conservation advocates already have done spadework to prepare the soil.

What is the sign that a market is ripe for certification? Receptivity. Long before producers contemplate auditing their production processes for eco-labeling, environmental advocates will have begun to influence the market by building awareness. Scroll back a decade, and the 1990s’ spike in voluntary certification efforts correlates with a tilling of market soil that took place around the 1992 United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (the “Earth Summit”) in Brazil.[ii]

Above the talk of politicians, the buzz of eco-tourists and the throb of marchers and media came a clear and simple message at that summit, which drew 172 governments and more than 17,000 citizen-advocates to Rio de Janeiro: good development is sustainable development—or “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs."[iii] This message is becoming embedded in 21st century notions of healthy societal growth.

As a result, even though critics have found it easy to question the Earth Summit’s impact, our research suggests that nuts-and-bolts movements like eco-certification, which connect the notion of sustainable development to daily business and consumer practices, cannot be built without a foundation of awareness and receptivity that such advocacy lays. Identifying receptive markets is thus the necessary first step to a successful program. To achieve broad impact, certification must be perceived as a market benefit by participants in at least one of the major markets for the product under consideration.

Why would consumers and companies care about certification? Sometimes the reason is as basic as people caring about the world in which they live. Additionally, consumers tend to be interested in certified products when they can see some direct benefit in what they’re buying. For instance, people buying organic produce know exactly what they’re getting: fruits and vegetables grown without synthetic pesticides, sewage sludge fertilizer or genetic engineering.

For producers and retailers, interest in certified products often derives from the desire to have a secure supply (e.g., a large and healthy fish population); to build or fortify a brand; and/or to be responsive to consumer demand for certified goods. In the case of the Marine Stewardship Council (MSC), which eco-labels fish, the U.K. was a logical market to target, because major British retailers like Sainsbury’s and Tesco were interested in positioning themselves as environmentally responsible.

At the same time, commercially significant producers serving these receptive markets must be able to meet the standard of certification. The MSC felt that Alaskan wild salmon could pass inspection. One of its first certification programs matched U.K. demand to Alaskan wild salmon supply. In this way, the most effective certification efforts pay attention to demand for and supply of sustainable product. They care about customers and producers. Failure to balance demand and supply adequately is likely to create significant frustration in the marketplace, which can kill a certification program before it starts.

Where should certification programs look for ready markets? Many countries in Europe, with histories of conserving land and energy, are receptive to sustainably-produced goods. Some indicators: European companies lead the Dow Jones Sustainability Index and account for over 40 percent of the 455 companies participating in the Global Reporting Initiative, a voluntary program in which companies provide information on their performance relative to a set of sustainability guidelines.[iv]

But certifying sales into Europe is not enough to satisfy most producers nor, usually, enough to create broad impact. Effective certification programs look beyond their receptive launch market and continue to evaluate trends and activities in other key markets. The United States, an obvious target, is not yet particularly receptive to certified products. U.S. social and environmental groups are still seeding market awareness. Corporate reinforcement could come from European trans-nationals, however, or from niche firms aiming to differentiate products and tip the scales toward receptivity.

This sensibility led the MSC to focus resources very differently in Europe than in the United States. In Europe, where both industry and consumers value sustainable practices more highly, certified fish account for 1.5 percent of all seafood sold through stores in the U.K., versus 0.05 percent in the U.S. European branded fish processors and retailers already sell $73 million of MSC-labeled fish like salmon and hoki, and European mega-retailers—including Sainsbury’s, Tesco, Carrefour and Metro, which account for more than 80 percent of the U.K.’s food sales, almost 60 percent of France’s and a third of Germany’s—all sell MSC-labeled products.

Large-scale European fish processors have also demonstrated interest in certification, in part for economic reasons—namely, to ensure a steady supply of fish. If certification succeeds in promoting more sustainable practices, it will help to ensure that targeted species of fish exist over the long-term and may take the place of harsher forms of control, such as regulation, which can prohibit the fishing of certain species entirely. Indeed, Anglo-Dutch Unilever—one of the world’s largest purchasers of whitefish, buying 250,000 metric tonnes of fish a year at a consumer value of 1 billion Euro—co-founded the Marine Stewardship Council in 1997 with environmental advocacy group World Wildlife Fund for this very purpose.[v]

In Europe the problem is supply, which can’t keep pace with the strong demand for certified fish. One European food-service operator told us, “We would like to carry as much certified fish as possible.” A European retailer lamented, “Some certified fisheries are not big enough to supply one of our stores for two weeks.”[vi] The MSC encourages and Unilever pushes, both aiming to move non-certified fisheries like Alaskan pollock, arguably the world’s most valuable fishery, to join the ranks of certifiers. Meanwhile, the MSC continues to build partnerships with European food processors and retailers.

In the U.S., however, where consumer awareness of and demand for certified fish remains low, few retailers save organic grocery chains use the MSC label when they sell wild Alaskan salmon, and no MSC partnerships yet exist with major branded U.S. processors. EcoFish of Portsmouth, New Hampshire, a rapidly growing niche distributor of eco-friendly seafood, was one of the first U.S. fish distributors the MSC certified for chain of custody. While EcoFish saw revenues rocket 250 percent to $3 million in sales in 2003 and finds retail customers willing to pay a quality premium for certified species, founder and president Henry Lovejoy says EcoFish has “not had a single request” for the MSC’s blue and white label on its packaging.[vii]

Conventional retailers don’t believe U.S. consumers care. Given this situation, the MSC has limited scope for action until environmental advocates stimulate demand. One starting point: foundations like Packard and environmental groups like Greenpeace have developed “good fish” guides that red-list over-fished species and green-list well-managed fisheries, which they give away to consumers through aquariums and conservation groups across North America. And campaigns such as “Caviar Emptor” and “Give Swordfish a Break” by organizations like SeaWeb and Natural Resources Defense Council also serve to raise consumer awareness.

Pushing, Not Just Setting, the Standard

Even when the market is receptive, setting the right standard can be tricky. For starters, the standard has to elicit voluntary compliance; most certification programs involve independent non-governmental bodies that develop standards for sustainability, and invite companies to agree to perform up to that standard. In each case, certifiers hope market forces, like more eco-sensitive demand, will create incentives for the broader industry to operate in a more sustainable manner.

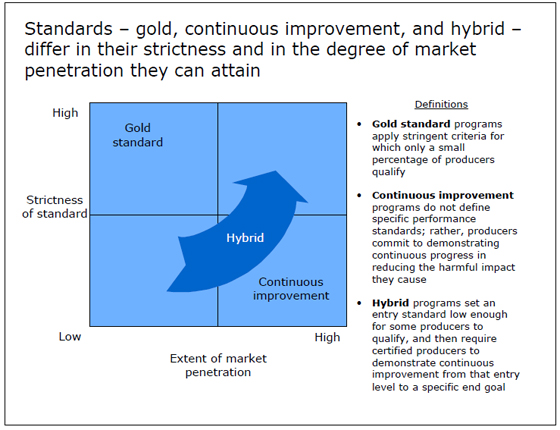

This means that if certifiers are too purist, few producers may be able to qualify; a movement pegged to a stringent gold standard, may fail to gather momentum. (See Figure 2: Certification standards – the dynamics of influence.[viii]) Early in a certification system’s development, when market benefits have yet to be demonstrated, this is especially true. The Forest Stewardship Council of the U.S. (FSC-US) was founded in 1993 with logging standards that are among the most rigorous in the world. By 2003 it had certified only 2.6 percent of U.S. timberland, or just 13 million out of 504 million acres.

On the other hand, if certifiers bank on continuous improvement—a less strict form of certification whereby producers commit to demonstrating continuous progress in reducing the harmful impact they cause, but do not have to meet specific performance standards—the influx of certified producers with unsustainable practices can set the quality bar too low. The American Forest & Paper Association’s Sustainable Forestry Initiative (SFI), an industry-sponsored certification program launched in response to the FSC-US, opened its doors a year after the FSC-US and initially had very low standards and no outside monitoring. But the standard’s ease gave it reach. By 2003, the SFI’s membership touched 136 million acres of the most intensely harvested U.S. timberland, or ten times the FSC-US’s penetration.

What’s the answer? At least part of it lies in pushing, not just setting, the standard, through either a hybrid solution or dynamic interaction among standard setters in a given industry.

Figure 2: Certification standards—the dynamics of influence

A hybrid solution carves out a middle ground by allowing a commercially viable number of producers to enter the system and by growing the certification program’s impact as standards become more stringent. Hybrid certifiers set guidelines that allow in enough producers with above-average practices to create a sort of gravity force that draws others to the standard. An ideal hybrid sets the entry hurdle as low as possible without alienating too large a portion of the environmental community. At the same time, hybrid solutions continue to raise the bar, because expectations ratchet up in a set fashion until producers ultimately meet the certifier’s goal. The Marine Stewardship Council adopted this approach, setting an entry standard that major fisheries like Alaskan wild salmon could meet. Today, ten fisheries worldwide—with species ranging from rock lobster to herring—have met MSC’s certification standards and a dozen more have entered the process.

Established thoughtfully, gold standard programs can also push and challenge overall industry standards; a rigorous certification organization can trigger a defensive industry response that becomes a steppingstone toward compliance. Consider again the case of the Forest Stewardship Council and the Sustainable Forestry Initiative. As mentioned, the FSC-US holds logging to a standard considered the most environmentally stringent in the world, and its certified acreage is only one-tenth the size of SFI’s. But if you take into account its influence on SFI, FSC-US’s impact is much broader than its direct reach suggests. Over the medium term, SFI has opened its performance to third-party audits and formed an independent standard-setting board, in large part because of the stake in the ground planted by the FSC-US.[ix] In at least one area—procurement systems—the American Forest & Paper Association claims that SFI has surpassed FSC-US specifications. The SFI requires wood processors to check NatureServe, a database of biodiversity hotspots, when procuring internationally, whereas the FSC-US, which also protects biodiversity, does not.[x] SFI’s point may split hairs, but its broader implication is clear: as iron sharpens iron, one standard is honing another.

As these examples suggest, there is no one “right” model. Securing support from certain environmental organizations, for example, will probably require a gold standard scheme. Alternatively, if producers cannot meet a gold standard, starting with a continuous improvement or hybrid approach will be necessary; as the situation evolves and matures, it may be possible to move to a gold standard.

Regardless of which model is chosen, the other aspects of the certification program must align with that choice. All standard setters must clarify issues and challenges at each step of certification, such that a producer’s or processor’s progress is observable, measurable, and takes place within a defined timeframe. And they need to establish real consequences, like loss of certification, if a producer fails to progress. As important, all models should find practical ways to influence producers outside their membership.

Looking again at the Marine Stewardship Council, its hybrid standards exert influence by developing a single set of principles and criteria that certifiers can apply, case-by-case, to craft guidelines for each fishery. The program allows more producers through the door, because it certifies fisheries that, while exceeding minimum legal requirements, may still have issues to address. Moreover, an MSC-certified fishery can use the MSC logo on its products as soon as it pledges to take corrective actions called for in its audit. This approach not only draws in more producers, but also influences corporate buying programs, creating momentum by stoking supply.

All participants must also understand and embrace the standard setter’s vision and approach. Clear communication is critical to galvanizing supporters with different motivations to march toward a common goal. For MSC, achieving broad impact in the seafood industry means identifying a number of fisheries to bring onboard. By clearly articulating targets, the MSC aligns its own global efforts to urge target fisheries to apply for assessment and inspires other organizations—say corporate buyers—to reach out to and lobby the same targets. Philanthropic organizations, like the Packard Foundation, which support certification, know where to offer subsidies for assessments. Yet none of these stakeholders can advance the ball until the MSC signals clearly what it is trying to achieve and how. Standard setters have to communicate effectively and even “sell” their plans so that likeminded organizations can work in synch. Without a plan, subscribed to by all, resources fail to reinforce each other or, worse, end up working at cross purposes.

Setting and implementing any standard can be complicated, in large part because it involves stakeholders beyond the standard setter. But a well thought-through process goes far beyond the base criteria for certification; it pushes each party involved directly or indirectly to strive for higher goals and purer practice.

Creating and Attractive Proposition For Producers

A receptive market and an effective standard with an aligned certification program can provide for a great start, but to keep gaining momentum the system has to offer a value proposition that attracts an increasing number of producers. To this end, reducing risk for suppliers, by driving down and justifying the cost of certification, is key. For example, Katie Fernholz, the Institute of Agriculture and Trade Policy’s (IATP’s) former forest certification project manager, reduced costs of certification for small landholders in the Great Lakes region by creating a group certificate program—an umbrella process that engages natural resource professionals to maintain quality control and standards, while small landholders work with the IATP to harness Global Information System technology to meet monitoring requirements.[xi]

An attractive value proposition is equally important for large-scale producers. When the Alaska Department of Fish and Game considered certifying the Alaskan salmon fishery to Marine Stewardship Council standards, it faced an audit that could cost up to $100,000. If the fishery passed inspection, the department would have to ensure through annual audits that fishermen continued to comply with restrictions on gear used, species caught and locations fished to protect and renew the salmon population. The question for the department, naturally: Would the MSC stamp on Alaskan salmon truly help to sustain production and make Alaska’s supply more competitive on the open market, justifying the effort and expense?

To answer that question, the department looked for signs from the industry that certification would strengthen wild salmon’s market niche against intense competition from farmed salmon.[xii] As important, the department needed assurance that consumer and environmental groups would support the move. A worst-case scenario saw raising awareness of the fishery only to draw attacks on some aspect of its operations. With these assurances in hand, the department obtained support from both the standard setting body—the MSC—and the Packard Foundation, which funds marine conservation, to subsidize two thirds of the cost of certification. The MSC gave the fishery its stamp in 2000 after Scientific Certification Systems sampled bycatch (the capture of non-target species in salmon fishing gear), tested compliance with international fishing treaties, and sought multiple evidences of stock sustainability. The supplier benefit? MSC-labeled Alaskan salmon has since developed a $35 million presence in Europe, a receptive market for certified fish that Alaska had barely penetrated.

Wholesalers and retailers can also play a powerful role in appealing to producers. It is difficult for certifiers to propel systems on their own, given that the money and manpower devoted to any certification system typically pale in comparison to the resources of its target industry. But certifiers can harness broader resources by motivating wholesalers and retailers to pull producers into the system.

The time is ripe. Certification’s rise in the new millennium comes in part because consumer pressure groups increasingly hold brand owners responsible for practices throughout their value chain. A recent survey by Environics of 25,000 global consumers showed that at least two-thirds of consumers in the U.S., Canada and major countries of Western Europe form their impressions of a company based on its ethics, environmental impact and social responsibility, and less than a third are basing their opinion on a brand’s reputation or quality.[xiii] Since 2002, environmental groups successfully have pushed companies like Staples office products to reform their supply chains to protect endangered forests and have prodded global financial institutions like Citigroup to prohibit investment in extractive industries that endanger ecosystems.

At the same time, the real test of progress lies in consumer behavior. In the U.S., mainstream consumers are not demonstrating that they will spend more time shopping for eco-friendly products or pay more for such products. Because of this, eco-certifiers say that corporate and government buying policies are the lynch pin for moving eco-certification mainstream.

For example, as one of the largest processors of white fish, Unilever’s push for certified fish and its willingness to change its own processes to meet MSC standards has had a ripple effect throughout its distribution channels. Said Mark Ritchie, president of the Institute of Agriculture and Trade Policy (IATP) in Minneapolis, Minnesota, which distributes MSC-labeled product in the Mid-West: “MSC is tiny, but Unilever is giant, so [the MSC] reached a tipping point before it was born.”

Unilever recognizes certification as a means to reduce risks to their business and brand. And Unilever is not alone. One hundred-and-sixty European companies today are listed on the Dow Jones Sustainability Index, alongside 79 North American firms, 43 Asian firms and 23 from other parts of the globe. Unilever, a bellwether for corporate responsibility, says procuring from sustainable fisheries required “a couple of million” euros worth of changes to its processes and systems, and while it’s hard to correlate revenue growth to the move, the investment has been critical to brand building and to securing a sustainable supply of fish.[xiv]

Dierk Peters, Unilever’s international marketing manager for the frozen foods sustainability initiative, stated, “This effort is about reinforcing brand preference, which we see as a precondition for profitable growth. On the one hand, it would be unrealistic to expect the consumer to pay a price premium for certifying seafood, as we are already at the upper end of the price scale compared to the competition. However, we are involved in certification because we want to assure a steady supply of fish to sell and maintain our leading brand image.”[xv] In an example of wholesaler-retailer symbiosis, by 2005, Unilever aims to source up to three-quarters of its fish from sustainable sources, ideally MSC-certified, while retailer Sainsbury’s announced plans to distribute only MSC-labeled fish by 2010.[xvi] These initiatives create enormous incentives for fisheries to ante up for certification audits.

A similar story is playing out in other sectors where certification has directly engaged industry. After mega-publisher Time, Inc. told International Paper, which has major paper plants in Minnesota, that it wanted to move its publications to certified paper by 2006, Minnesota entered into a certification process with the FSC-US for all state forests.[xvii] In the Fair Trade sector, which guarantees farmers a living wage for their commodity, regardless of world market ups and downs, Starbucks, which buys 2 percent of the world’s coffee, in 2003 nearly doubled its Fair Trade coffee purchases of certified beans to 2.1 million pounds.[xviii] Major U.S. roasters like Green Mountain and Dunkin’ Donuts have also upped Fair Trade purchasing.

Consider the boost this gives to distributors of Fair Trade coffee, and to the producers themselves. One such distributor, Equal Exchange of Canton, Massachusetts, is a worker cooperative that markets Fair Trade coffee grown in Latin America and Africa. In 2003, Equal Exchange’s staff brought together Fair Trade coffee producers for a time of experience sharing, training and celebration at a YWCA in Boston. Merling Presa Ramos, the general director of a Nicaraguan coffee co-op called PRODECOOP was one of many Latin Americans to attend. She explained how in 1993 small coffee producers in Nicaragua came together to form a cooperative aimed at producing organic coffee for the Fair Trade market. This market was particularly attractive because organic coffee commanded a higher price and “Fair Trade” guaranteed at least some margin to producers regardless of fluctuations in world prices.

Nonetheless, many farmers were daunted by the idea of converting to organic production, a move that would require them to re-cultivate their fields and to adopt new approaches for fertilizing soil and controlling pests. A few entrepreneurs took the plunge, made a success of it, and the rewards inspired others.

A decade later, with major roasters and retailers pumping demand, Fair Trade coffee is netting producers two premiums. Because of its Fair Trade practices, Equal Exchange pays a minimum of $1.26 a pound for non-organic coffee, a price 58 percent higher than the 2003 conventional market price of 80 cents-per-pound. A producer like PRODECOOP also receives an additional 12 percent premium, or 15 cents-per-pound for certified organic coffee. With 40 percent of her co-op’s production now sold under Fair Trade terms, Presa calls every pound sold a symbol of hope for her country. “Years ago, coffee was often sold below production prices,” Presa said. “Under Fair Trade terms our producers can earn a dignified living. It means we can survive and send children to school…with food in their stomachs. It means we can think about the future.”[xix]

Organic Agriculture:Example of Certification Moved Mainstream

That sort of vision is at the heart of one story of certification moving mainstream—organic agriculture. A sector with one of the most mature certification programs, organic agriculture saw its first U.S. farms voluntarily certified in the 1970s. More than thirty years later, with organic certifiers and certified farms multiplying and with a crescendo of producers and consumers lobbying, the U.S. government ruled on a national standard for organic labeling. Since October 21, 2002, the United States Department of Agriculture’s (USDA’s) “Organic Food” label has identified foods at least 95 percent certified as free from synthetic pesticides, genetic engineering and sewer sludge fertilizer, among other criteria.

The USDA label doesn’t connote the highest existing standard; it represents a homogenized norm drawn from about 100 U.S. and international certifiers of organic agriculture, many with more stringent specifications. But the green and white label, a national standard, has raised awareness among consumers and lawmakers in a way that fragmented certification programs struggled to, and it shows how far the movement has come in engaging influential stakeholders.

Mark Ritchie of IATP says that although a national standard tends to validate, not raise existing voluntary standards, it helps the movement immensely by facilitating inter-state trade and creating consumer awareness. “[The USDA] process saw organics written up in the newspaper all the time,” said Ritchie. “It is fair to say that there are many factors that have driven growth in the organic market. Getting a national standard really put organics in the news and raised awareness.”[xx] A year after the USDA ruling, U.S. legislators put forward the Farm-to-School Bill, which aims to move fresh farm produce, including organics, into the federal school lunch program, a potential windfall for producers.[xxi]

The government didn’t engage overnight; many organizations laid groundwork over decades and lobbied the USDA to build a program. Rather, the story of organic food certification testifies to the importance of orchestrating stakeholders pre-certification to move eco-labeling mainstream. For organic food, that journey began more than 60 years ago, when pioneering farmers like the Rodales of Pennsylvania moved beyond producing toxic-free fruits, vegetables and grains and hormone-free animals, to advance the science of organic farming and to educate other farmers and consumers on its health merits. By 1972, this family-farmer-led movement gave rise to the first international certification organization, the International Federation of Organic Agricultural Movements (IFOAM), which today certifies any organic food to be shipped across a border.

That same year, a Chicago man named Gene Kahn moved to Washington state and founded Cascadian organic farms, one of the first certified food processors in the U.S. By the turn of the millennium, mainstream food companies like Nestlé, Kraft and General Mills had begun looking to health and organic brands for growth. In 1999, General Mills bought Cascadian’s Small Planet Foods brands, including organic breakfast cereals, frozen fruits and vegetables, fruit spreads and prepared meals. In 2000, Kraft bought Boca Burgers, a healthy, soy-based alternative to grill meats. Meanwhile, organic food retailers like Whole Foods and Wild Oats established and expanded chains, and conventional grocers began to set aside more shelf space for organic lines. All of these stakeholders had moved certification forward by the time the federal government, in 2002, not only ruled on an organic food standard, but also entertained a bill that could transform its purchasing.

Setting and communicating direction, orchestrating stakeholders and influencing action takes time, but no less than the time required to form a common front. Anthony Rodale, chairman of the Rodale Institute on organic agriculture and a third generation organic farmer, sums this up, “Everything has to evolve and develop at the same time. We need to educate and create more awareness for consumers…the distributors and retailers are the biggest front line…the service sector is huge, including public schools and catering, and that’s a smart way for government to be involved…You need people working together…Certification is the only way forward to regenerate not only our land [and resources], but also our health.”[xxii]

Conclusion

What have we learned? Certification systems take time to develop and deliver—time to build credibility with a broad array of stakeholders, to establish even a toehold in a major market, and to realize environmental and social impact. Three principles are worth bearing in mind when evaluating certification programs:

· Meeting the market: While certification is a market-based approach, it relies on environmental advocacy to soften the market and build receptivity. Certification can only gain traction where consumer awareness creates demand for eco-friendly product and corporate buyers recognize the business value of sustainable production.

- Pushing the certification standard: An effective standard allows the best producers in the sector to qualify and creates a means for well-intentioned producers to begin a certification process and ratchet up standards to meet the ultimate goals of the program. Truly stringent, or “gold,” standards like the FSC-US have narrow reach, but can be effective where they successfully challenge industry bodies to improve overall performance. Regardless of the type of standard, standard-setting bodies need to be clear about what they’re trying to do and to align other stakeholders with their strategy.

- Creating an attractive value proposition for producers: Reducing risk for suppliers by driving down and justifying the cost of certification is key to drawing them in. Corporate or government buyers turn out to be the lynch pins in this effort. A sign of health and good prospects for any certification system includes major pull from buyers like Unilever for certified fish or Starbucks for Fair Trade coffee.

So what’s next? Certification is one of the newest approaches to achieving more sustainable production. And it has captivated crusaders. Old hands like Anthony Rodale, who had Rodale Farms certified in 1995 to set an example for the farmers it trains, say certification is the future, even though today he counts only 12,000 organic growers in the U.S., out of two million farms. Phil Guillery of Dovetail Partners, a market maker for certified wood products, feels forest certification has hit a tipping point, even though three quarters of U.S. woodlands remain uncertified. Guillery points to major woodland states like Minnesota that have applied in 2004 to certify their state forests. Others like Michigan and Wisconsin are actively reviewing the question. Their successful audits would double FSC-US certified timberland. Meanwhile, FSC International and the U.K. have initiated a joint review of the U.K. forestry norms to take into account FSC guidelines and European Community standards. Direct impact is growing.

Certification’s influence is growing, too. To ensure a high-quality supply of coffee, Starbucks has opened a farmer support office in Costa Rica, one of the world's biggest coffee producers. In addition, it’s revamping a program, called CAFE Practices, that award price increases to coffee suppliers who make environmental and social improvements to reduce agrochemical use, conserve energy, abstain from child labor, pay workers more and give them access to housing, water and sanitary facilities. While none of the actions stem directly from Fair Trade certification, they constitute points on a continuum toward assuring sustainable production. "You can't have a sustainable (farm) if you're mistreating workers and mistreating the environment," said Willard "Dub" Hay, the company's senior vice president for coffee. He said that Starbucks will pay 5 cents more per pound for one year to suppliers who meet 80 percent of its social and environmental criteria. Suppliers can receive two more one-year price increases if they make other big improvements.[xxiii]

Some activists applaud such efforts. Others say the big companies are not going far enough. Social responsibility advocates have called some retailers of Fair Trade products to task for using the Fair Trade cachet to inflate margins.[xxiv] And smaller roasters committed to 100 percent Fair Trade beans, like Dean’s Beans and Just Coffee, criticize the big coffee companies for purchasing only a minority of their stock under Fair Trade terms. But Ritchie of the IATP, says supply, too, needs cultivating. “If [Starbucks] went to 100 percent, they would put all the other Fair Trade buyers out of business. The tipping point can be a drowning point if you are not careful.”

Meanwhile, certification programs in forestry, fisheries, diamonds, electricity and many other products are picking up the pace. Have they delivered either the market or environmental and social impact that their proponents hope for? Not yet. Can they do so? The jury is still out. But with the proper support and enough resources odds are that certification will play an important role in making development more sustainable.