Opportunities to do more good are seldom in short supply for nonprofits that provide potentially life-changing services to individuals in need. So it’s not surprising that growth tends to be a recurring topic among their leadership and supporters. Or that the basic question, “Can we do more?” quickly gives way to more detailed queries such as, “Could we think about adding programs, sites or both?” “What would growth entail for our staff, systems and existing organization structure?” “How much new funding would it take to grow, and how could we acquire the necessary funds?”

In 2006, questions like these were once again surfacing for Barbara Duffy and her leadership team at MY TURN (aMerica’s Youth Teenage Unemployment Reduction Network, Inc.). The organization had developed a three-year business plan in 2003 that envisioned significant growth in the number of communities and youth it was serving. Within two years, the team had knocked the ball out of the park and met all of the plan’s goals. Now, in the wake of their successful growth phase, MY TURN’s leaders were energized to do more.

At the same time, however, they were concerned about the speed of the organization’s growth and their ability to attract sufficient funding. As Duffy put it, “We were like sprinters in a race who finished running and then wanted to watch the film to analyze our form. We needed to reflect on how we had grown, whether anything was lost in that growth, and how we wanted to invest our time, energies and resources going forward.”

My Turn At a Glance

MY TURN was founded in 1984 in Brockton, Massachusetts to help Brockton High School students who were not planning to attend college find jobs and make the transition from school to work successfully. Operating out of an office in the high school, MY TURN initially consisted of three full time Career Specialists and one part time Executive Director who collectively helped Brockton High School seniors learn interview skills and search for jobs.

Fueled by early success, the organization took advantage of opportunities to open sites in neighboring communities. It also added programs to support youth who had dropped out of school, and programs to support students who wanted to attend college. By 2003, MY TURN was serving more than 1,100 youth, ages 14 to 21, in eight small Massachusetts cities, with approximately 27 full- and part-time employees, through three program areas:[1]

- Reconnecting Out-of-School Youth targeted young people who had dropped out of school, helping them to complete their education or to find a job by enrolling them in job readiness training, workplace learning, occupational training, or school.

- Connecting to Work focused on career-bound high school students, helping them build professional and interpersonal skills and providing them with opportunities to explore different careers through employer partnerships.

- Connecting to College also served in-school students, providing, among other things, SAT test preparation, college tours and workshops on financial aid.

MY TURN’s demonstrated success brought it to the attention of the Edna McConnell Clark Foundation (EMCF). And in late 2003, MY TURN engaged in a strategic planning initiative with EMCF and Bridgespan that resulted in its first formal growth plan. The plan called for expanding into six new communities (including one in New Hampshire—the first outside of Massachusetts) and for clustering the communities the organization served geographically. It also added new management capacity, set new performance metrics so that Duffy and her team could monitor progress more easily, mapped out ways to improve program quality and assess program effectiveness, and laid out the investments needed to achieve those goals. To fund the expansion, the organization raised $3.1 million and doubled its annual operating budget to $2.6 million.[2]

By 2006, MY TURN had achieved all of the growth milestones laid out in the plan—a year ahead of schedule. With renewed support from EMCF, MY TURN engaged with Bridgespan once more, to help chart the next phase of growth.

Framing the Challenge of Growth

As they began to think about MY TURN’s future, Duffy and her team were acutely aware of the tens, if not hundreds, of thousands of youth throughout New England who were living in poverty, out of work or both. Given this level of need, what should MY TURN seek to do next? Should it provide more services to more kids in existing communities? Or should it focus, instead, on expanding its programs throughout the state? How important was continued growth beyond the Massachusetts state line? Duffy had fielded calls from leaders of organizations based as far away as Florida who were interested in MY TURN expanding to their cities. Was now the time to consider national expansion?

A working team, comprised of Duffy, other MY TURN leaders, and Bridgespan consultants, was formed to undertake a two-and-a-half month planning project. The key questions on the table were:

- What are MY TURN’s three- to five-year growth goals?

- What is the right replication model for MY TURN in the short term? Should MY TURN open new branches? Or should the organization rely on other nonprofits or individuals to do so?

- What are the financial implications and organizational requirements of each of these alternatives?

Envisioning the Next Stage of Growth

MY TURN’s long-term vision (articulated during the first formal planning phase, in 2003) is straightforward: by 2018, serve over 5,000 young people directly, throughout New England and New York State. In addition, they want their program to be a model for other organizations across the country. To map out the next steps toward realizing this vision, the team first identified several dimensions on which to evaluate potential growth trajectories. Their bottom line was what each would translate to in terms of MY TURN’s ability to serve its beneficiaries. Drilling down, that meant understanding the effect each path would have on MY TURN’s ability to:

- Attract funding;

- Leverage existing assets, including its infrastructure (e.g., systems and processes) and its relationships with external stakeholders (e.g., employers and school systems);

- Advocate for the beneficiary population;

- Gain specific knowledge of the beneficiary population;

- Recruit managerial talent.

The team also wanted to be sure they understood how big the organization would have to be in any given location to achieve significant benefits. It was one thing to understand whether MY TURN could garner the resources to offer services out-of-state; it was another to understand what it would take for the organization to excel in new locales. If, for example, MY TURN went national, exactly how big would the organization have to get in order to maintain its current high standard of service to beneficiaries? It wouldn’t be enough to plant a flag and establish a presence in another location. Duffy and her team wanted to ensure that MY TURN could provide a level of service in any new location that was equal to what it was currently providing.

Serving More Youth at MY TURN Locations

As the team worked through the evaluation criteria, the value of having significant scale at a local level quickly became apparent. Local growth could increase MY TURN’s access to local funding through individual donors and area institutions. Getting “big” in this way could also help the organization strengthen existing relationships with vendors and schools, which in turn could result in reduced costs. For example, the costs associated with starting up new sites, such as finding space, recruiting staff and attracting youth to a program, would be lower if such connections were already established.

Scaling up locally would also allow MY TURN to leverage certain fixed costs. The organization could, for example, share instructors across sites and pursue more robust relationships with employers. Finally, such local growth would give MY TURN a “home court” advantage when it came to gaining additional knowledge about the target beneficiary population and advocating locally for beneficiaries. They would be building on a base of knowledge, rather than starting from scratch.

One important caveat, weighing in on the negative side of expanding more deeply into existing local venues, had to do with a primary funding source. In 2006 more than half of MY TURN’s funding came from site contracts with Workforce Investment Boards (WIBs), which grant Workforce Investment Act (WIA) dollars. Each WIB covers one primary city along with several nearby communities. When MY TURN grows to the extent that it has approximately three case managers in any given WIB area, that WIB often will not grant additional funding—even if MY TURN’s current penetration of the target community is only at a fraction of what it could be. Therefore, any plan to expand locally came with the understanding that it was unlikely that MY TURN would get funding for more than three case managers in any given WIB’s geography.

Expanding to New Communities in Massachusetts

The team next turned to the merits of continuing to expand throughout Massachusetts. State scale, they concluded, was also important on several fronts—funding in particular. WIB directors within a state communicate at monthly meetings and biannual conferences. If MY TURN had a reputation as a high-performing organization in multiple WIB areas across the state, then expanding within the state could lead to increased funding from WIBs that were not currently funding the organization.

Beyond funding, state expansion also could boost MY TURN’s ability to attract talent. If MY TURN could increase its name recognition throughout the state and if its reputation also became more widely known the hope was that, increasingly, highly-qualified individuals would seek out the organization as a potential employer. Finally, state scale would enable MY TURN to do advocacy work for impoverished and unemployed youth on a state government level. Doing so also could enhance MY TURN’s brand; the increased presence could help the organization attract additional funding and possibly even a line item in the state budget.

Expanding Beyond Massachusetts

When the team considered growing into neighboring states (beyond MY TURN’s limited presence in New Hampshire), they found some attractive funding opportunities. As in Massachusetts, WIB directors from neighboring states interact at multiple conferences and meetings; if MY TURN expanded into neighboring states, it could increase the number of WIBs from which it received funding. In addition, research on foundation funding suggested that scaling up in multiple neighboring states could attract funding from national foundations—national expansion wasn’t necessarily needed. Finally, like in-state growth, multi-state growth could enable MY TURN to increasingly attract high-quality talent. Ultimately, however, the team decided against setting multi-state expansion as a top priority, given that the costs of expanding into a new state were greater than they would be with an in-state expansion.

As for national expansion, MY TURN leaders and Bridgespan team members did not pursue this idea to the same extent as the other options. Although they hypothesized that one potential benefit of national reach would be an increased ability to advocate for the beneficiary population, the team realized that if MY TURN wanted to advocate effectively at the national level it would need to be a far larger organization. MY TURN leaders did not envision the organization growing to that extent in the near term. And since the organization was likely to be able to attract national funding even if it expanded within multiple states, “going national” was ultimately deemed unimportant—at least during the planning period in question.

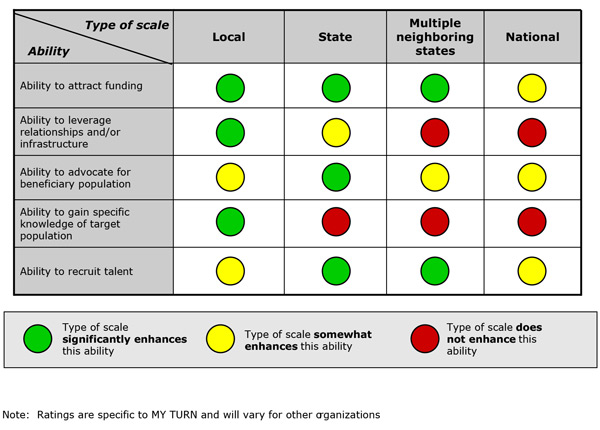

The team’s overall conclusions about which abilities would be enhanced for MY TURN relative to the various types of scale are summarized in Exhibit 1.

Exhibit 1: MY TURN Ability vs. Scale Comparison

Having decided where to grow, the next decision was how. To that end, they defined four ways that MY TURN could reach additional youth:

- Add a case manager in an existing program (to maximize program size);

- Start a new program in an existing community;

- Enter a new community in an existing region;

- Expand to a new region.

The team explored each option, working from least to most resource intensive. First, they determined that several MY TURN programs could accommodate an additional case manager without going over the WIB limit and jeopardizing additional WIB funding. Then they identified existing MY TURN locales that didn’t yet offer all three programs.

The next step was to select communities in regions where MY TURN already had a presence that were good candidates for expansion. Here the team focused on understanding which communities needed MY TURN the most, and which ones most resembled those in which MY TURN had already been successful. To address the second issue, they evaluated the candidates based on demographic “fit” with MY TURN’s target population, potential for geographic clustering of MY TURN sites, and availability of funding (e.g., WIA or other location-specific funding). They also assessed those communities’ level of interest in/demand for MY TURN (e.g., underperforming WIBs, lack of good providers), and the presence of potential partners (e.g., career centers, educational and employment outlets, day care providers). These same considerations also would inform MY TURN’s expansion into new regions, once it had reached full potential in existing regions.

Ultimately, the group determined that MY TURN’s growth initiative for the years 2007-2009 would be to expand to scale in existing communities, then expand to full scale in the six existing regions, and finally to expand into one new region. As MY TURN achieves scale in existing regions within Massachusetts and New Hampshire, leadership will consider expanding to additional states to achieve more benefits of regional scale. The team also articulated the organization’s plans for the longer term. In 2010-2017, MY TURN plans to expand to full regional coverage throughout New England, including New York, and explore alternatives for spreading the MY TURN model to new regions and organizations across the country.

A Model for Replication

The team next needed to select a model for replication. Up until 2006, the organization had grown by opening new sites itself (“branching”), with Duffy and her team managing and fundraising for all expansion efforts. This approach had worked well, enabling MY TURN leadership to keep tight control over all sites and collect a great deal of performance data. However, as MY TURN leaders considered the prospect of further growth, they wondered whether it now made sense to entrust other organizations or individuals with the opening of new sites.

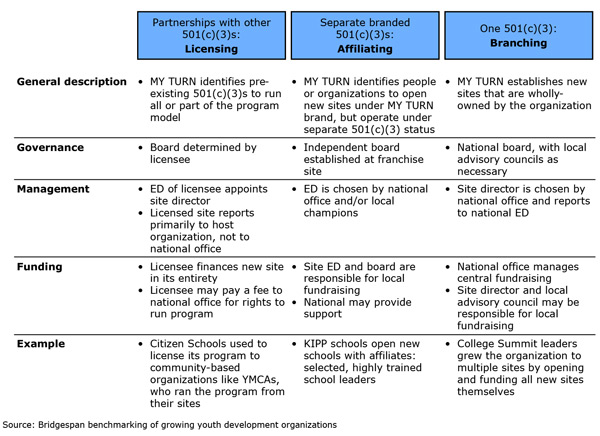

MY TURN and Bridgespan put three approaches to replication on the table for discussion: licensing, affiliating, and branching. To replicate through licensing,MY TURN would identify pre-existing 501(c)(3)s to act as partners and run all or part of a MY TURN-designed program. Replication through affiliating would mean identifying people or organizations to open new sites under the MY TURN brand, but operate under separate 501(c)(3) status. Each option presented its own set of strategic, organizational and financial implications. Further detail is provided in Exhibit 2.

Exhibit 2: Three Possible Approaches to Replication

The team knew that there is no universal formula for selecting a replication model. Each model offers certain advantages, although these are not a given. Similarly, each is prone to specific disadvantages, which a replicating organization will have to find ways to minimize or be comfortable living with. As a result, picking the right model is a matter of determining the factors that are most important to the organization at this specific point in its growth trajectory (for example, speed of growth or consistency across sites) and then identifying the model that tends to promote those factors most strongly while not introducing any unworkable characteristics. The task, then, was to vet each model in the context of MY TURN’s situation.

To do this, the team tapped various sources. Bridgespan shared the experiences of other clients, drew from a Bridgespan study of 20 youth-serving organizations, and researched additional examples.[3] Complementing that fact base, Barbara Duffy interviewed several executive directors of similar organizations that have grown significantly using different replication models. As Duffy noted, “It was extraordinarily helpful to talk to other EDs. I saved myself a lot of money and aggravation by asking others about why their decisions worked or didn’t work for them, and then figuring out how those lessons applied to MY TURN.”

Exploring Licensing

As Duffy and her team reviewed the information they had gathered, they quickly eliminated licensing from the set of options. Licensing had a number of advantages, not least the potential to allow an organization to grow more rapidly than other replication models. It was also simple, in the sense that it did not require starting new organizations or offices. What’s more, it was a lower-cost alternative, because each site bears a funding burden. However, licensee arrangements also carry certain risks, including the possibility of competing programs within one site. If a licensee were running several programs with overlapping beneficiaries or services, for example, management might be strained, and tight resources stretched even thinner. In addition, licensee arrangements also had relatively high attrition rates, with organizations generally committing for only a couple of years and dropping programs thereafter. Finally, the team wanted to maintain a certain standard of consistency across programs. Even though they might have been able to control for consistency with strict licensee agreements, they remained uncomfortable with the relinquishing of control implicit in licensing.

Comparing Affiliating and Branching

That left affiliating and branching on the table. Was now the time for MY TURN to switch from branching to affiliating? For affiliating to be preferable, the team would have to believe that it could equal or out-perform branching on several key characteristics:

- Speed of growth: Could affiliating allow MY TURN to achieve its growth goals more quickly than branching, leading to the establishment of a larger footprint?

- Control over implementation: Could the quality of programs and data collection be as consistent with affiliates as with branches?

- Ability to attract funding: Could affiliates raise sufficient funds from a range of sources, including local sources, to support each new site. And could MY TURN headquarters raise sufficient funds to support its own operations and provide value to a network of sites?

- Availability of partners: Were there potential partners that could be trusted to maintain the integrity of the MY TURN model, as well as deliver the same level of program quality?

Speed of growth

To assess whether growth would be faster with the affiliate model than with branching, the team reasoned that affiliate sites would be able to serve the same number of youth as branches could, assuming the model was implemented faithfully. The experience of several youth-serving organizations that had pursued different replication models showed that many of the affiliate organizations had grown more quickly, with the few that hadn’t attributing their slower growth to site attrition. Given MY TURN’s track record of managing quality and relationships, the team assumed that attrition and site closures would be minimal. The team concluded that MY TURN could likely grow more quickly through the affiliate model.

Control over implementation

The most critical consideration with respect to control over implementation was whether MY TURN had codified its program model clearly enough for others to follow it with fidelity. Duffy and her senior managers ascertained that the model was thoroughly codified, down to its key element—the case manager. Over the past few years, MY TURN had explicitly articulated the characteristics of a good case manager, the desired and required parameters of case manager interactions with youth, and the reporting requirements for case managers. Although it is difficult to codify a human interaction perfectly, MY TURN had already opened several sites with new management and employees, and these sites were operating with fidelity to the model. So even though the situations were not exactly comparable, this experience led the team to conclude that the model could be implemented with fidelity by an affiliate. The team also discussed ways in which MY TURN could maintain approval or veto rights over the hiring of case managers, even in an affiliate model, which would provide more control over this critical component. Additional control measures could be implemented to enable data collection from affiliates.

Ability to attract funding

The team next examined whether MY TURN affiliates and headquarters would be able to raise sufficient funds to support one or more affiliate sites. Duffy estimated that affiliates would need to raise approximately $75,000 per year of local funds in order to cover the basic costs of running a site with one program manager. Although there was no way to confirm whether partners would be willing and able to raise such sums, this seemed like a reasonable expectation, given that it fell within the wide range of fundraising that other organizations required of their affiliates. As for the fundraising MY TURN would need to do to support a larger network, the team relied on the organization’s history of being able to support its earlier growth plan. Moreover, Duffy also had engaged in several conversations with interested funders, which indicated potential for MY TURN to raise additional funds for growth.

Availability of partners

To assess whether enough partners existed for MY TURN, the team first defined the characteristics that would make a nonprofit or governmental organization a satisfactory partner:

- A high quality organization with a strong reputation;

- A target population similar to MY TURN’s (i.e., has experience with at-risk youth and has a means of recruiting youth into the program);

- Ample fundraising capacity (e.g., willing to raise funds, could possibly win a WIB contract, and would pay a fee for affiliation);

- Respect for MY TURN program (e.g., would prioritize the program and implement the model with fidelity);

Team members then looked systematically for organizations that would fit the bill. Among nonprofits, YMCAs and community centers were among the potential partners. But although the team identified individual organizations in some of the communities that could likely be affiliate partners, management worried about quality control issues and the administrative burden of working with several separate licensees simultaneously.

On the government side, possible partners included school districts, WIBs, and one-stop career centers. But here, too, ultimately they were unable to find an organization that they thought would be willing to prioritize MY TURN’s program in the majority of the communities they wanted to enter. For example, school districts exist in all communities, but MY TURN leaders knew that districts would not hesitate to cut MY TURN programs in case of budget shortfalls.

Thus, the team concluded that no promising partners systematically existed for MY TURN. This realization was quite a surprise for the team members. They had anticipated that other variables—such as fidelity to the model—would present more of a challenge to MY TURN’s use of an affiliate model. Because of the lack of promising partners, the team realized that the affiliate model would not work for MY TURN, and that continuing to open its own branches was the best option.

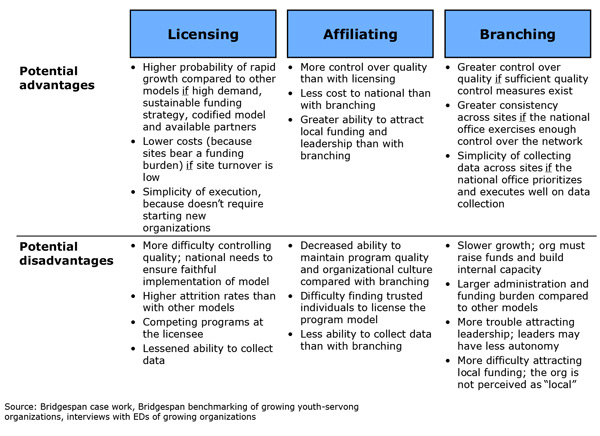

A summary of the general potential advantages and disadvantages that the team discussed for each of the replication models is shown in Exhibit 3, in descending order of importance.

Exhibit 3: Advantages and Disadvantages of Replication Types

Sustaining Growth with a Branch Model

With the decision to use a branch model made, the team turned to implementation, and the task of zeroing in on the right speed of growth, and the capabilities and number of people needed to support a larger, more geographically distributed organization. Also, because MY TURN would be funding this growth entirely, MY TURN leadership needed to take concrete steps toward creating a sustainable funding model, even given the likelihood of further financial support from foundations.

Setting a Target Growth Rate

What would be a reasonable expectation for growth over the next three years? To tackle this issue, the team used an iterative process, first determining their ideal growth goals in terms of number of new case managers, new programs, new communities and new regions; next using a financial model to cost out these goals; and then making revisions based on the cost information. MY TURN leaders were careful not to set the growth projections so high as to jeopardize the organization’s long-term sustainability.

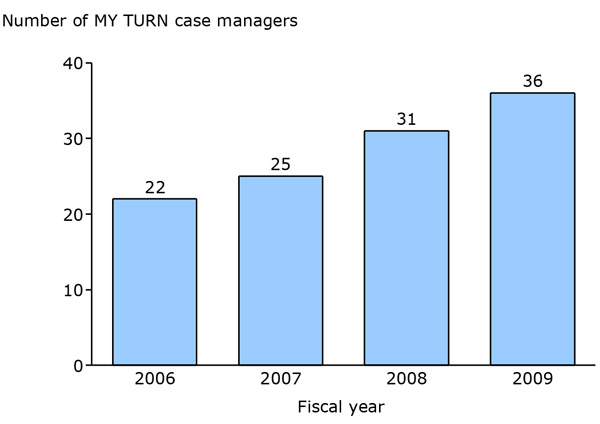

The team settled on growing the number of case managers from 22 in fiscal year 2006 to 36 in fiscal year 2009, as shown in Exhibit 4.

Exhibit 4: MY TURN Case Manager Growth Projections

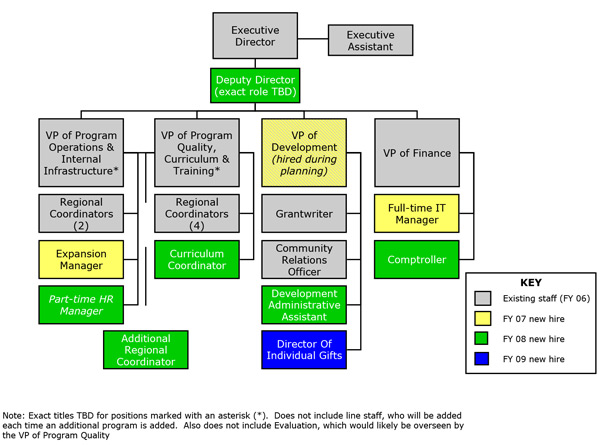

Adding to the Organizational Chart

In order to support what was termed “rapid but controlled growth,” the team determined that it needed additional capacity across the board, but particularly in the senior management ranks and the development department, along with improved Regional Coordinator capabilities.

Senior management

The first task was to decrease the burden on Duffy; she was already overextended, and further growth would require her to take the helm of a bigger organization with larger fundraising requirements, a more distributed staff and more external commitments. To provide her with much-needed support, the team decided to create a “Deputy Director” role. The new Deputy Director would have general management responsibilities, assist with program support and expansion through the brokering of key relationships with key stakeholders, and support and assist the development department with the fund development plan. Another benefit of adding this position was the possibility that the Deputy Director could be groomed as a successor to Duffy, since the other two members of the senior management team had been open about not wanting to take on the ED role in the near future.

Because Duffy and her two senior managers estimated that collectively they had only 25 hours per week to spend on issues related to growth, the team discussed the merits of adding another senior manager to focus solely on growth. Duffy ran this idea by multiple seasoned EDs of growing nonprofits and received their strong endorsement. MY TURN leadership made plans to hire an Expansion Manager in FY 2007, to coordinate and support efforts to deepen and expand MY TURN offerings in existing and new regions, as well as lead start-up efforts and fundraising research in the new region.

To allow for growth of the senior management ranks, the roles of Duffy’s two senior managers were also restructured somewhat, to give one more oversight on expansion and the other more focus on curriculum and training.

Development

At the beginning of the planning process, MY TURN’s development staff consisted of a full-time grant writer and a part-time development officer, who was managing all fundraising. In order to supplement the organization’s development capabilities, the team asked the part-time development officer to transition to full-time and take on the title of Vice President of Development. Her responsibilities were to continue to oversee the development department and lead all fundraising, including experiments to pursue sustainability. This adjustment was enacted during the team’s planning period with Bridgespan. Also, in order to support the Vice President of Development and equip the development department to meet fundraising goals, the team made plans to hire a Development Administrative Assistant and a Director of Individual Giving.

Regional coordination

Because the growth goals would require the Regional Coordinators (“RCs”) to take on more responsibility related to assisting growth and raising local funds, MY TURN determined to embark on an ongoing training and development program to boost the management, communication and leadership skills of RCs. Additionally, the plan called for the hire of an incremental RC, to take on leadership of the new region to be added in FY 2008.

Overall, discussion of goals for expansion and financial modeling of costs resulted in a plan to grow MY TURN’s management by 55 percent and line staff by 67 percent over the next three years. As these additions to the staff were discussed, the team created a tentative managerial map for 2009, as shown in Exhibit 5.

Exhibit 5: Proposed 2009 Managerial Map

Making Other Improvements

Finally, the team discussed other improvements that would be needed to sustain a larger organization. They agreed on systems improvements including a new telephone system, increased office space, and implementation of a performance management software system called Efforts to Outcomes. Additionally, MY TURN leaders took this opportunity to refine their communications, branding and marketing materials to better represent the organization to external constituencies.

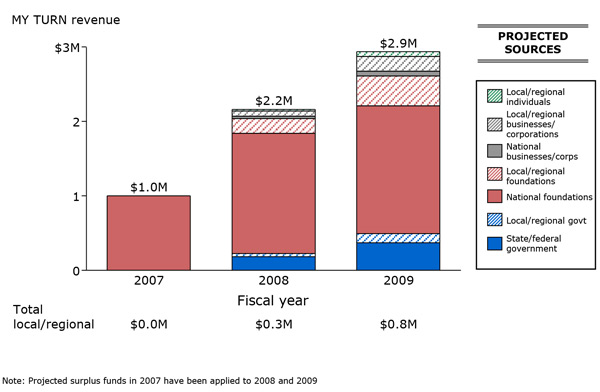

Establishing a Sustainable Funding Model

Bridgespan determined that MY TURN needed approximately $12.7 million in total over the next three years in order to support its growth plan. (Calculations showed that the yearly budget would increase from $2.6 million in FY 2006 to approximately $3.5 million in FY 2007, $4.3 million in FY 2008 and $4.9 million in FY 2009.) Of these total costs, WIA dollars plus committed funding were expected to cover $6.6 million, leaving a funding gap of $6.1 million.

One option for filling the gap would be seeking additional funding from national foundations. This approach was not new to MY TURN, which had experience with national funders. The team concluded that going forward, this was a viable option. MY TURN had experienced great success in attracting national funders, current national funders were still interested in supporting MY TURN, and additional funders had expressed interest in providing support.

However, MY TURN leadership also wanted to explore the possibility of raising local and regional funds, particularly given the organization’s focus on deepening within communities and understanding their specific needs more fully. Thus, leaders of MY TURN resolved to build a more sustainable funding mix by being more purposeful about bringing in additional local and regional funds. As part of this agenda, they plan on having Regional Coordinators take on more fundraising responsibilities within their regions. Because there is some question as to whether this model will work, the concept will be tested, with two of the RCs seeking to raise $25,000 each from local sources.Exhibit 6 lays out the projected composition of funding sources for the $6.1 million funding gap.

Exhibit 6: Projected Sources of Funding

Investing in Governance

The resolution to expand to more geographically dispersed locales raised the issue of governance; the team recognized the need for a board structure that better drew from and reflected the communities in which MY TURN operated and would operate.

In 2006, MY TURN had a single board of directors. The board had been “professionalized” as a result of substantial changes made during the execution of the organization’s earlier growth plan; they were more capable than earlier boards with regard to advising MY TURN about fundraising, donations, contacts and skills. Going forward, however, Duffy and her senior managers decided that the current single board of directors should be replaced by multiple regional advisory boards and a central “governing” board. The regional advisory boards would support and assist Regional Coordinators with leadership, fundraising and expansion. They also would help to assess specific local needs and provide contacts to local officials—in short, to better connect to communities. Finally, they would serve as “feeders” for the governing board, which would provide oversight of the MY TURN organization and support and assist the Executive Director with leadership, fundraising and expansion.

Growth in Progress

Nearly one year into the organization’s next phase of growth, MY TURN is once again ahead of its own schedule. Strategically setting a course of action and working to integrate new management into critical positions such as Expansion Manager (since renamed Director of Strategic Growth) have already leveraged year-one growth greater than what Duffy and her team envisioned. For example, MY TURN has added a case manager in Lynn, Massachusetts, and has also added programs in communities including Fall River and Leominster, Massachusetts, and Nashua, New Hampshire.

MY TURN also has expanded into Rhode Island. When the organization received a call from the mayor of Pawtucket, Rhode Island, asking if MY TURN would consider expansion there, Duffy and her team were able to consider it in the context of their new plan for growth, and determined that the opportunity was a good one to pursue (even though it was a bit ahead of the curve in terms of their planning). In April 2007, MY TURN opened up offices in the state of Rhode Island through a grant from the Greater Rhode Island Workforce Partnership, providing the organization with growth in not only a new region but a new state.

All six Regional Coordinators have successfully recruited members for geographically disbursed Regional Advisory Boards which has enabled the governing board to begin to solidify its plans to become more invested in the overall financial operation of the growing organization.

And MY TURN has received several significant new grants, including $367,000 through the Massachusetts Executive Office of Public Safety’s Shannon Grant Initiative, and $125,000 from the Amelia Peabody Foundation. Some of the new grant money supports programs; some supports administrative expenses.

Business planning during phase one of MY TURN’s growth in 2003 was critical to the ultimate objectives of MY TURN’s senior leadership team. The strategy, research and thinking that were developed during this first stage of planning provided the entire organization with a methodical blue print that, in essence, transformed MY TURN. But Barbara Duffy is convinced that re-visiting and re-thinking the major structural decisions has added great value, and has once again enabled the organization to “leap out of the gate” in this next phase of growth.

As she put it, “Our strategy—the business plan we created in 2004—showed us how to capitalize on opportunities while still adhering to our mission and the ‘blueprint’ we developed. By re-visiting those successes, researching our options, and re-thinking the next phase of growth in light of our infrastructure needs and capabilities, we’ve been able to continue along that trajectory. We’re able to be flexible, but also to ensure that our growth is strong and sustainable.”

Sources Used for This Article

[1] MY TURN was serving an additional 700 youth through a partnership with another organization.

[2] For more information on the organization’s 2003 growth plan, please see the Bridgespan case study, “MY TURN, Inc.: Preparing for Regional Growth,” available at www.bridgespan.org.

[3] This study, “Growth of Youth-Serving Organizations,” is available at www.bridgespan.org.