Summary

NFTE has developed a curriculum with an award-winning textbook and workbook for teaching young people to start and run businesses, and has created a network of programs in communities across the globe. The organization has grappled with such issues as how to widely deliver its program while protecting the integrity of its model; how to delegate maximum responsibility to local sites and find the right local site talent; and how to run an extensive network effectively from a national office. Developing a new strategic plan and adding strong management talent have helped NFTE manage these complex issues.

Organizational Snapshot

Organization: National Foundation for Teaching Entrepreneurship

Year founded: 1987

Headquarters: New York City, New York

Mission: “To teach entrepreneurship to young people from low-income communities to enhance their economic productivity by improving their business, academic, and life skills.”

Program: NFTE’s national office has five program areas: teacher education at NFTE University; program partner support; alumni services; research and evaluation; and curriculum development. NFTE University offers an accredited entrepreneurship training program for youth-development professionals and teachers who are planning entrepreneurship programs at their schools and organizations. The three- and five-day courses take place at NFTE’s national office in New York during the year, and over the summer at university partners around the country, including Babson College, Georgetown, Yale School of Management, Stanford University, and the European Business School London. NFTE also operates or partners with programs that teach its curriculum to students at the local level in the U.S. and internationally. NFTE sells books, teaching materials, and videos of its curriculum, which include the award-winning book How to Start & Operate a Small Business, which NFTE distributes through a partnership with Pearson. BizTech 2.0 is an online version of the curriculum developed in partnership with Microsoft. To date, NFTE has worked with over 3,200 teachers and more than 100,000 low-income young people worldwide. In the fiscal year ending in June 2004, the organization reached over 18,000 young people.

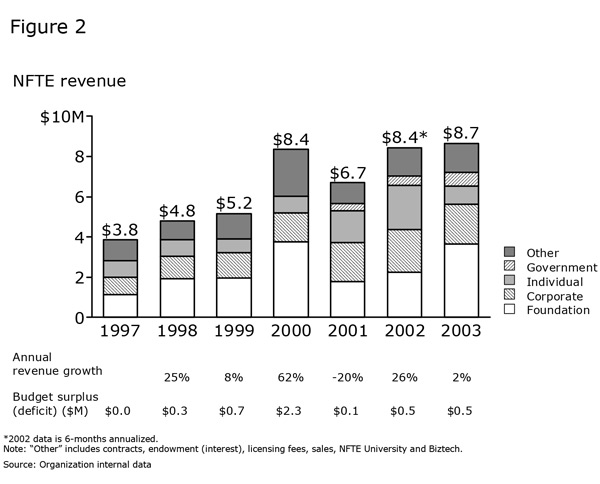

Size: $8.7 million in revenue; 48 employees (as of 2003).

Revenue growth rate: Compound annual growth rate (1999-2003): 14 percent. Highest annual growth rate (1999-2003): 62 percent (2000).

Funding sources: NFTE has a diverse funding base, but relies most heavily on foundations, which comprised 42 percent of total funding in 2003. Corporations provided 23 percent, and just under 17 percent came from a combination of contracts with other organizations, interest on the NFTE endowment, licensing fees, and other earned income fees. Individual donors (11 percent) and the government (8 percent) made up the remainder.

Organizational structure: NFTE is a 501(c)(3) that operates branches, affiliates, and licensees throughout the world. Regional offices are in New York City, NY; Chicago, Illinois; White Plains, New York; Babson Park, Massachusetts; Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; San Francisco, California; and Washington, D.C. NFTE has six international programs, and seven national partners in smaller cities around the U.S.

Leadership: Steve Mariotti, president and founder; Mike Caslin, chief executive officer

More information: www.nfte.com

Key Milestones

- 1987: Began offering services in Newark, New York City, and Philadelphia

- 1990: Expanded to Wichita, Detroit, Chicago, and Minneapolis

- 1991: Expanded to New England; centralized the finance function and began to standardize curriculum

- 1993: Expanded to Pittsburgh

- 1994: Expanded to Northern California; developed its first performance scorecard

- 1994: Expanded to Washington, D.C.

- 1995: Promoted Caslin to CEO, sharing leadership duties with Mariotti; launched NFTE University, a national teacher-training center; entrusted certified teachers (not just NFTE staff) to deliver the program

- 1998: Began an intensive strategic planning process

- 1999: Launched BizTech, an online learning site developed in partnership with Microsoft; started its first international operations, in Belgium and Argentina

- 2000: Developed a more ambitious strategic growth plan

- 2001: Brought in COO David Nelson

- 2003 Re-entered Chicago

Growth Story

The genesis of the National Foundation for Teaching Entrepreneurship dates back to a life-altering event. Steve Mariotti was mugged in New York one afternoon in 1981 by a group of youths, who beat him severely when they discovered he had no money. To confront fears that surfaced after the beating, he quit his import/export business and began teaching typing and bookkeeping in the most neglected parts of the New York public schools.

By 1987, Mariotti had developed a novel curriculum of teaching math and reading skills through a class about entrepreneurship. He had kids fill out sole-proprietorship forms, print business cards, write business plans, register their businesses, build relationships with wholesalers, make sales calls — everything required to start and run a small business. He even gave them small startup grants. “Right away I knew I had something,” he commented in a 1994 Harvard Business School case study. “You’d have these guys sitting in the back and they’d be saying, ‘Oh screw you … blah, blah, blah,’ and two weeks later they’d be acting like MBAs.” Ten businesses got off the ground in his first year.

Mariotti knew he had found his life’s work. He felt that teaching disadvantaged youth about business was the key to encouraging them to take responsibility for their own lives and to make something of themselves and their communities. He formed NFTE in 1987, and attempted to finance the fledgling group by writing to 168 people on the Forbes list of richest people. He got only one reply, from private investor Ray Chambers, which led to a $60,000 contract to teach elementary and junior high students from the Boys and Girls Club of Newark, New Jersey.

Programs grew opportunistically from there, including an inmate program at Rikers Island Prison in New York City and a community outreach program with Wharton School in Philadelphia. Mike Caslin joined as a fundraising consultant in 1988 (he later became CEO in 1995), which freed up Mariotti to focus on developing curriculum and teaching. Positive national press spread the word about NFTE, leading to nearly $500,000 in funding and 1,000 youth served within two years.

The organization expanded regionally in response to funders’ interests and national-office employees who wanted to move. A Wichita, Kansas-based organization called the Youth Entrepreneurs of Kansas licensed NFTE’s curriculum and teacher training in 1990, backed by the Koch Family Foundations.

Funders encouraged NFTE to established programs that year in Detroit, Chicago, and Minneapolis, but all three closed shortly thereafter. “It was great to start something new, but we didn’t understand how to manage multiple sites,” said Mariotti. According to Mariotti, NFTE emerged from this experience with an understanding of the importance of raising enough money locally to sustain an office over multiple years, and a clearer picture of the characteristics of a successful site leader. “Success is fragile,” says Mariotti. “In some organizations, even being alive is fragile.”

In 1991, NFTE set up a successful New England site, which remains a branch of the national network. Pittsburgh opened in 1993 after NFTE received support from the Scaife Family Foundation. A Northern California office came in 1994, and Washington, D.C., opened with Koch Family Foundations support in 1994. The organization went back to Chicago in 2003.

Six international sites were added over the years, because Mariotti felt that there should be no limits to where NFTE could go. “A kid is a kid, so I don’t want to have any barriers to reach them,” he says.

NFTE currently measures the quality and efficiency of the services it delivers, and it is working with Harvard to do more research on students’ academic outcomes. As of early 2004, NFTE students’ interest in reading had increased by 4 percent, a statistic made even more impressive when compared to declining interest in a comparison group and, more broadly, a national long-term declining trend in reading interest from 7th grade through high school. Moreover, the students’ interest in attending college had increased 32 percent, as compared to a decrease of 17 percent in a comparison group. Career aspirations showed improvement, as well.

In 1994, NFTE developed its first performance scorecard, which helps NFTE see both the outcomes and progress against organizational goals across the field offices. Mariotti recognizes both the benefits and limitations of monitoring the field offices. “The scorecard allows us to see quickly when things are going bad,” he says. “We cannot yet forecast when things are going bad, but at least we are making progress.”

NFTE launched NFTE University at Babson College in 1995 as a national teacher-training center. In a wide-reaching organizational change, teachers were certified to teach NFTE’s curriculum, and were entrusted to carry it out without great oversight. “We made a cultural decision to trust teachers and youth workers, not just NFTE professionals, to deliver the program,” says Caslin. “This was not a simple decision. Steve’s mission model was to be as close as possible to every student. But we realized that was not scalable as a movement.”

By 1998, Caslin and Mariotti had developed a system to manage multiple sites that involved granting autonomy to well chosen and trained divisional leaders (see the Configuration section).

An intense strategic planning process began in 1998 that led to an internal plan called “Vision 2005.” Caslin described a “teacher-centric” organization that would train 10,000 teachers and reach 1 million students by the year 2005. And in 1999, NFTE launched BizTech, an online learning site developed in partnership with Microsoft.

By 2000, NFTE had trained over 1,500 teachers and served over 33,000 young people. It operated six regional offices, which had autonomy over fundraising and programs. But the group was far from reaching its ambitious goals. A meeting with the new Goldman Sachs Foundation in 2000 led to an intensive engagement with McKinsey & Co. to develop a strategic growth plan. Based on the results of that process, Goldman was prepared give a substantial grant to NFTE.

NFTE took a hard look at how to make the program as effective as possible. The growth objective that came out of the McKinsey engagement was summarized this way: “Maximize the number of on-mission students reached at the minimum program standard, leveraging scarce NFTE resources.” The minimum program standard involved using NFTE curriculum, NFTE-trained teachers, and a student-written business plan at the end of the class. NFTE’s role would be “to empower and enable teachers through recruiting, training, support and incentives.”

Reaching the maximum number of students required several operational and strategic shifts. One of the most important was stricter screening criteria for teachers at NFTE University, which helped to select the teachers who would be most serious about implementing the program when they returned to their schools. NFTE also decided to focus geographically around its regional offices, to take best advantage of its regional office structure.

Though the programs delivered through program partners are less expensive from NFTE’s point of view, with the partner assuming some of the costs, finding the best-quality partners has been challenging. Additionally, the partners do not serve the same critical regional fundraising role as the offices. Balancing these tradeoffs, the organization is expanding through a combination of its own sites and partner sites.

Going forward, NFTE plans to use program partnerships more strategically to lower NFTE’s costs and organizational strain, gain local knowledge, build relationships, and seed entry into new urban areas. It expects to double the number of partners, and triple the number of students served over the next five years by growing domestically in a planned, controlled, and fiscally responsible fashion. Internationally, it will expand with caution and only where it can find a partner. Optimal partners are local players that have: strong ties to schools in a community; a complementary mission to NFTE; an independent, sustainable funding stream; and the ability to meet NFTE’s standards for program quality. NFTE currently has 27 program partners, who reach about 45 percent of its students served.

Configuration

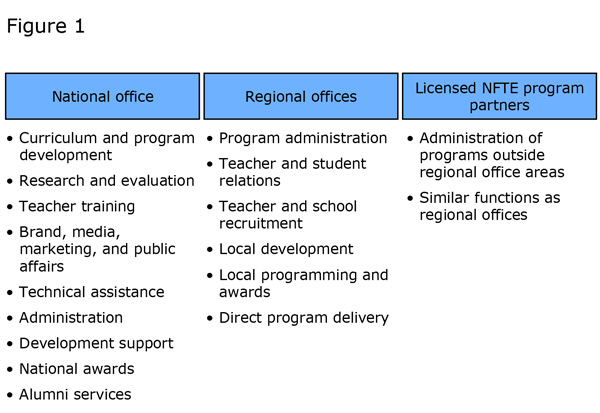

NFTE’s strategy is to partner with schools, universities, and community-based organizations to deliver programs, while focusing on developing innovative curricula; training and supporting teachers and youth workers; and providing supportive alumni services. NFTE accomplishes its strategy through program partners. The organization manages the majority of its partner relationships out of its national office, allowing its regional office staff to focus on building close relationships with schools and partners within a 1-hour driving distance. International affiliates are loosely managed, operating based on their own funding and according to a recommended program. (See Figure 1.)

Partners serve NFTE in several ways. For example, university partners host a “NFTE University” Certified Entrepreneurship Teacher education program to train educators and youth workers in the proper techniques for teaching entrepreneurship. Program partners like large national youth agencies, Cincinnati Public Schools, the NAACP, and TechnoServe branches in El Salvador, Ghana, and Tanzania license NFTE’s programs to bring entrepreneurship training beyond the scope of NFTE’s regional offices. These partners are established nonprofit organizations or government agencies “with a complementary vision and mission to NFTE’s and independent, sustainable funding streams.”

NFTE has found it easier to work with school system partners than with community-based organizations (CBOs). “The model to replicate the NFTE experience at community-based organizations doesn’t really work,” says Mariotti. “There is no ability for national organizations to dictate locally, so we would have to go to every local site [not just the national office]. School systems work better because you tend to get larger class sizes. Also, the school teachers are already trained; people in CBOs are youth workers [and generally are not yet trained in teaching techniques]. Teacher turnover is high; youth worker turnover is even higher. Attendance in school is not fantastic; after-school attendance is even worse. So you get the most bang for the buck by staying in school systems.” While some partnerships with CBO-run after-school programs have worked, such as Boys and Girls Club in San Francisco, NFTE has reduced its CBO-focused efforts.

NFTE has struggled with determining the proper configuration for its organization, wanting to balance innovation and widespread dissemination of programs with quality. Through these efforts over the years, the management team has learned that the following ingredients are needed:

- Centralized financial controls. “We decentralized finance to where people had their own checkbooks and checking accounts, because 10 years ago I believed each person would have his or her own business,” says Mariotti. “Essentially you were a franchise. It was a disaster from a record-keeping standpoint … We strongly recentralized in 1991.”

- Common procedures. “I’ve become more understanding of the value of a playbook,” says Mariotti. “A lot of the argument to have a playbook came from me as I came back from the anarchy. We’ve had a lot of false starts; we would do things and then distribute [procedures], forget about them and wouldn’t update them.”

- Shared best practices. “One of the things the [strategic] plan of 2004 said was to share best practices,” says Nelson. “Everyone was doing their own thing … We keep talking about [adopting the principles of the] playbook from the Green Bay Packers — they only did six to seven plays, but they did them well!”

- A redefinition of “control.” “I’m not sure what control means,” says Mariotti. “That term has always bothered me. I know for a fact that if we had more control in Kansas, it wouldn’t be as good a program. It’s not really about control. It’s about having the right people in place, and giving them the right training.”

Capital

NFTE has a diverse funding base, but relies most heavily on foundations, which comprised 42 percent of total funding in 2003. Corporations provided 23 percent, and just under 17 percent came from a combination of contracts with other organizations, interest on the NFTE endowment, licensing fees, and other earned income fees. Individual donors (11 percent) and the government (8 percent) made up the remainder.

NFTE has a number of major foundation supporters, with the Atlantic Philanthropies, Shelby Cullom Davis Foundation, and the Goldman Sachs Foundation each providing more than $1 million in support each year. Major corporate funders include Microsoft, Morgan Stanley, and Merrill Lynch, who are drawn to NFTE’s business-friendly mission. Although NFTE appreciates these large donors and relies critically on their support, the concentration of funding in a few donors is a challenge. “Fundamentally, we have a dangerous funding model,” says Nelson. “We get 90 percent of our funds from 10 percent of funders … but we are not growing the funding base as fast as we should.”

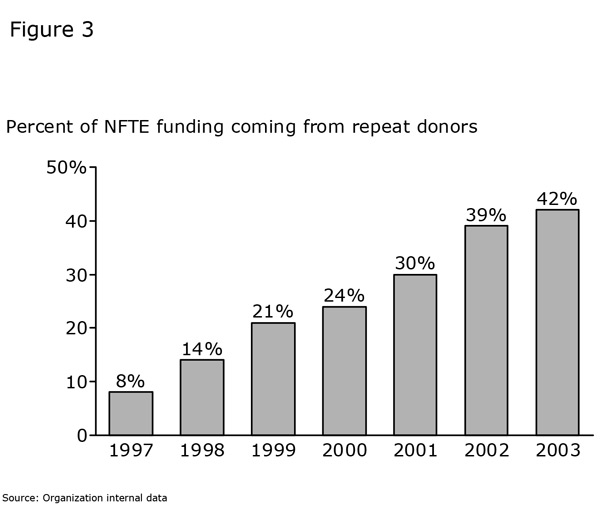

NFTE has been successful in using repeat funders to support growth. In 2003, almost 83 percent of NFTE’s foundation funding came from repeat funders, and 52 percent of individual donors were repeat donors. NFTE is not only able to retain donors, but it is also able to convince them to give more each year. (See Figure 3.) But individuals remain a fairly small component of NFTE’s overall funding mix, and the organization is working to strengthen its individual giving strategy.

Increasing the board’s role in fund development is another priority. As NFTE grew, it became clear to Mariotti that the organization needed a stronger board, both for strategic advice and for raising the funds necessary to provide the NFTE experience to more kids. Mariotti tried a novel approach to impress upon the prospective board members how much NFTE would value their time and energy: “I went out to recruit the ‘Seven Samurai’ for our board, and I said to them, ‘We’re getting ready for you. We’re not ready yet. But we’re getting ready, and in a year, I will be back.’” Mariotti returned a year later and all the board members accepted. The board has been instrumental in both strategy and fundraising, and is now an asset in NFTE’s capital campaign.

Capabilities

In the early days, Mariotti kept administrative costs low with a minimal office staff, hiring a few people here and there to teach and balance the books. His experience taught him that foundations would not be likely to fund organizations with high overhead costs. He ran the operation out of his apartment, and kids came to his door at all hours of the night and day for help and advice.

But by 1990, this had become unsustainable. Mariotti was teaching 700 hours a year and increasingly managing all the administrative aspects of running the organization. He worked seven days a week. The organization’s financial reporting was late, and cash flow was a constant issue.

In 1995, Mariotti began transitioning some of his workload to Caslin, who became chief executive officer that year. Mariotti focused on teaching and curriculum development, while Caslin focused on brand promotion, fundraising, and program performance. “Mike [Caslin] is a gifted person,” says Mariotti. “He can take four seemingly disparate points and connect them. Most of our breakthrough ideas — the partnership with Babson, the annual dinner which pays my salary, the BizTech site — all those ideas are Mike Caslin. He has a gift for strategy or creative things. You can go to him with any problem — he’ll see this circle as related to that circle, and put them inside a third circle, and it will all make sense.”

NFTE fared less well with its first chief operating officer hire. “[The COO] managed up well in his interactions with me,” says Mariotti. “But I was traveling a lot, and when I was here it was a lot different. It took about a year to realize what was happening.”

In 2001, Mariotti and Caslin brought on David Nelson from IBM as chief operating officer. Caslin is now the ideas and strategy person, Nelson handles day-to-day operations, and Mariotti remains to some extent involved in operations, but spends significant time in fundraising, external relationships, and curriculum development. “Dave [Nelson] does so much stuff, it’s impossible to say how he’s freed me up,” says Mariotti. “I’ve been able to put three times the time into curriculum. Almost every hard thing that would take me 100 hours, Dave does it and it’s 15 or 20 hours. This year, we got $2 million for our endowment. I never would have been able to work on that or think about it, had I not had a very senior-level executive to work on [the rest of the organization].”

One ingredient of success in this relationship is the clear lines of authority. “The thing I can’t pay Steve and Mike enough respect for is they said, ‘Dave, here are the keys to the car,’” says Nelson. “’Just get us where we need to go safely.’ That’s how they treated me. If you look up any organization’s history around getting some repeatable processes in place ? the landscape is littered with people who come to blows. The amount of times that has happened here is unbelievably small.”

The three-way power sharing arrangement isn’t perfect. Mariotti will pick up the phone and direct staff around the country, and staff will then hear something different from Nelson or Caslin. “I was thinking about it during the week, that that’s terrible,” says Mariotti. “But my conclusion is, it’s healthy. [Staff are] being exposed to three experienced people with different lines of thought. But what we need to do is regroup and talk to [staff] as a team.”

Staff training is a constant worry for the management team. “Tragically, we are making the most basic mistake in education,” says Mariotti. “We just can’t figure out this training thing [for NFTE staff]. We have multiple sites, with limited budgets. It’s that arrogance of assuming that you know what I know. This is why growth kills. You assume that someone else knows what it took you 20 years to learn. But it won’t kill us; we’re working on it.”

Staff turnover is another challenge, and Nelson is currently conducting an analysis to understand NFTE’s turnover. “We have a number of people who are leaving now for lifestyle reasons, graduate school, etc.,” says Nelson. “Most turnover is due to career enhancement and personal enrichment. One staff member left to start a foundation, and another one left to become a teacher.”

In 2001, NFTE began linking bonuses to its performance scorecard. “People are myopic about this scorecard, which is good and bad,” says Nelson. “The headquarters team and all the local site teams each receive a score based on how well they perform on the scorecard metrics. The bonus of anyone on a team is based 70 percent of how his or her team performed, and 30 percent on how the organization as a whole performed. This is intended to promote willingness to share, but it’s been a challenge. Sometimes people are not excited about doing things not on the scorecard.”

Developing effective local site leadership has also been a constant challenge. Over the years, by trial and error, NFTE has learned what to look for in an effective site director. According to Mariotti, they must be promotionally oriented, good communicators, externally focused, persistent, and able to reach out to the community. “[You need] someone who instinctively knows how to sell,” says Mariotti. “A mistake we’ve made repeatedly is we get a really good teacher, who understands teachers [but not the sales role or leadership].”

Key Insights

- Finding the right site directors. NFTE’s management team has done extensive thinking about the right personality for site directors. They’ve also learned that many entrepreneurial personalities need to be paired with a strong COO/organization-builder, at the site level as well as the national office.

- Building the right configuration. NFTE has spent considerable time working to develop effective relationships with its local sites. It has also thought through the most effective ways to get impact out of limited resources, such as training teachers to implement the program.

- Managing a concentrated funder base. NFTE has been able to both attract big funders and to keep them with the organization. The next challenge is to diversify the funding base and to build an endowment.

- Building the executive team. The CEO and president/founder long ago found a way to divide responsibilities for the best interests of themselves and the organization. And after a false start with the COO position, they’ve been able to integrate a COO well in the last few years. The leaders know their own strengths and surround themselves with executives with complementary skills.