“Strategic, targeted giving – in amounts within reach of private donors – can save lives and preserve the systems that protect them,” wrote Robert Rosenbaum, a leader of Project Resource Optimization, which has created a list of cost-effective, high-impact programmes ready for funders to support. “By distilling effective programs down to their core, evidence-based essentials, and channeling philanthropic dollars directly to them, we are piloting a model for a leaner and smarter aid architecture,” he contended.1

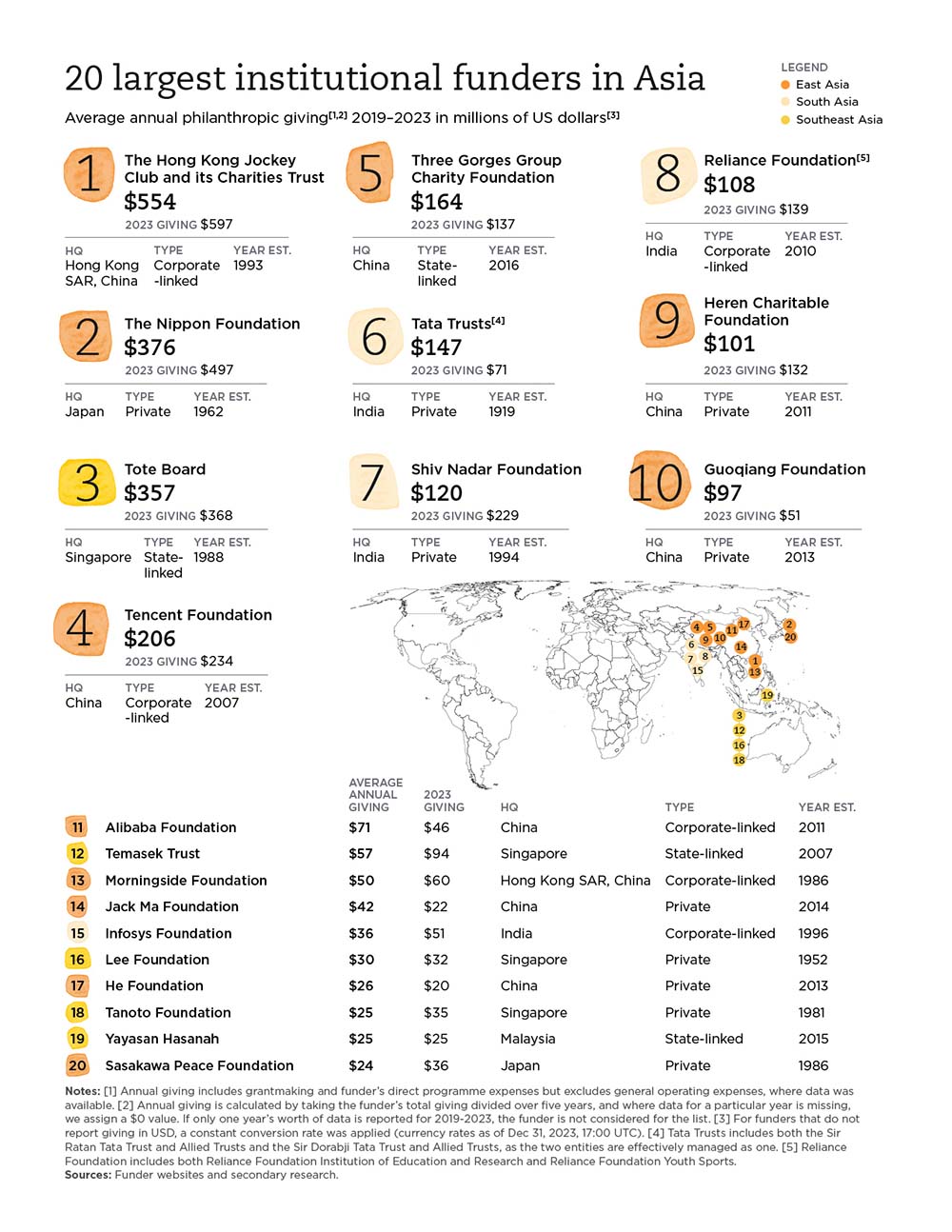

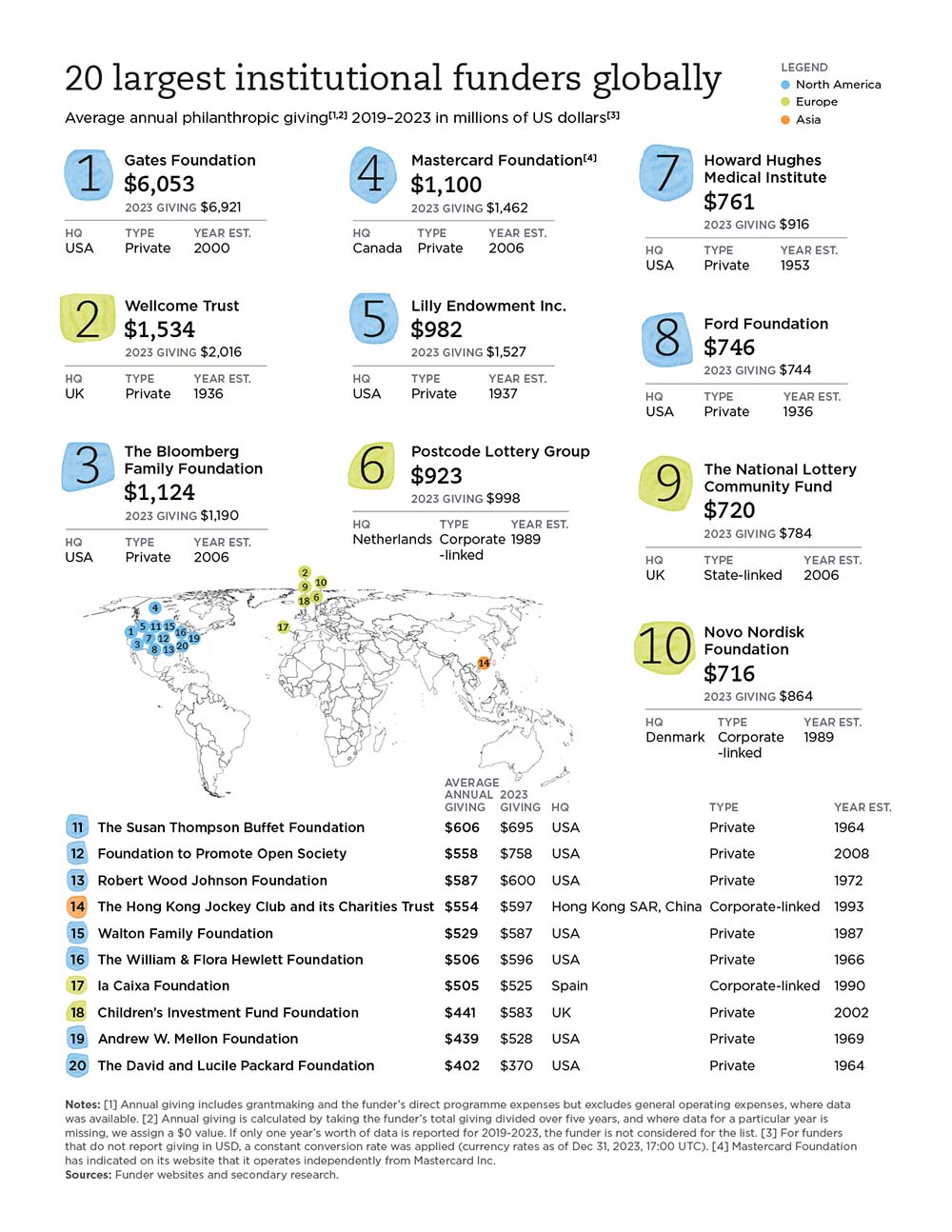

If history is prologue, there is reason to be optimistic about philanthropy’s response to current challenges. Through 2023, the most recent year for which we have data, leading global and Asian institutional philanthropies continued a trend of increasing yearly funding. To make this year’s list of the 20 largest funders, the minimum average annual giving from 2019 to 2023 ticked up 8 percent and 14 percent for funders globally and in Asia, respectively.

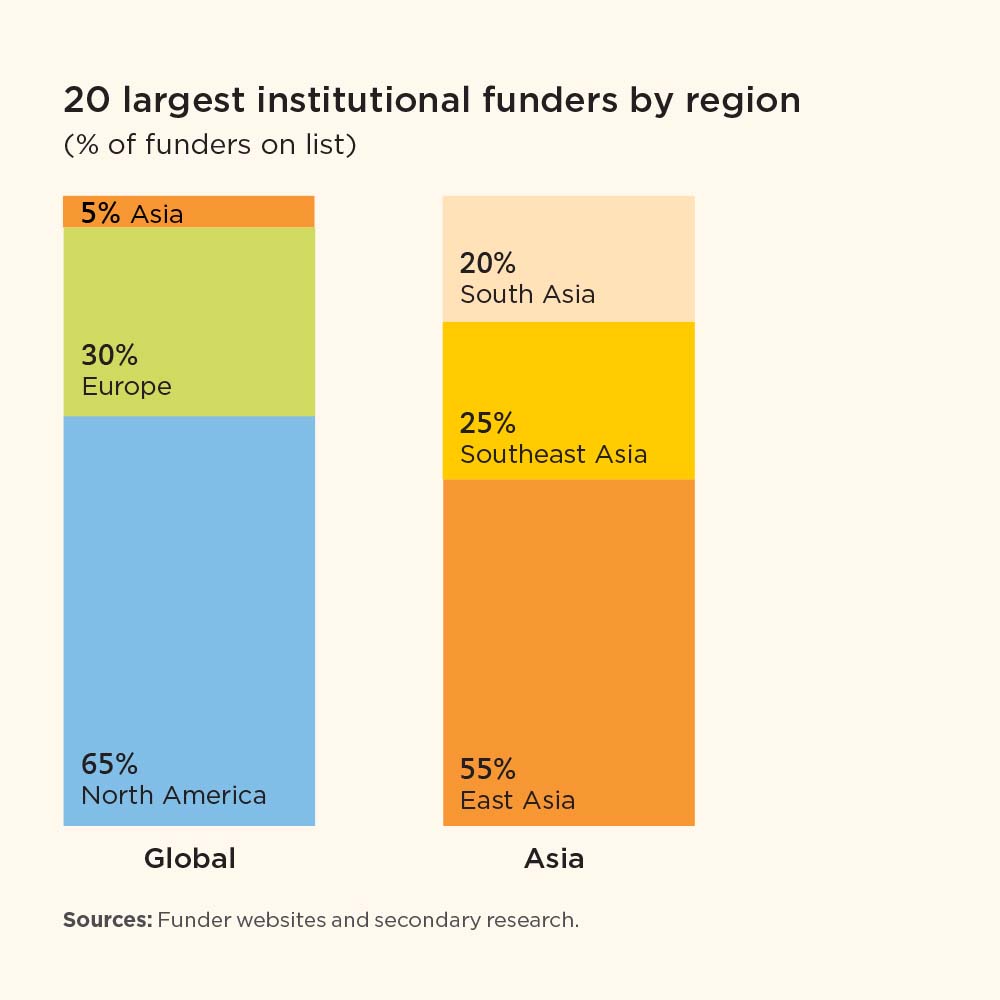

By institutional philanthropies, we mean private foundations, corporate-linked foundations2, faith-based foundations3, and state-linked entities focused on philanthropic work4. (See “Methodology.”) Globally, 19 of the 20 largest funders are based in North America or Europe, while 11 of the 20 largest in Asia are based in two East Asian countries, China – including Hong Kong SAR – and Japan.

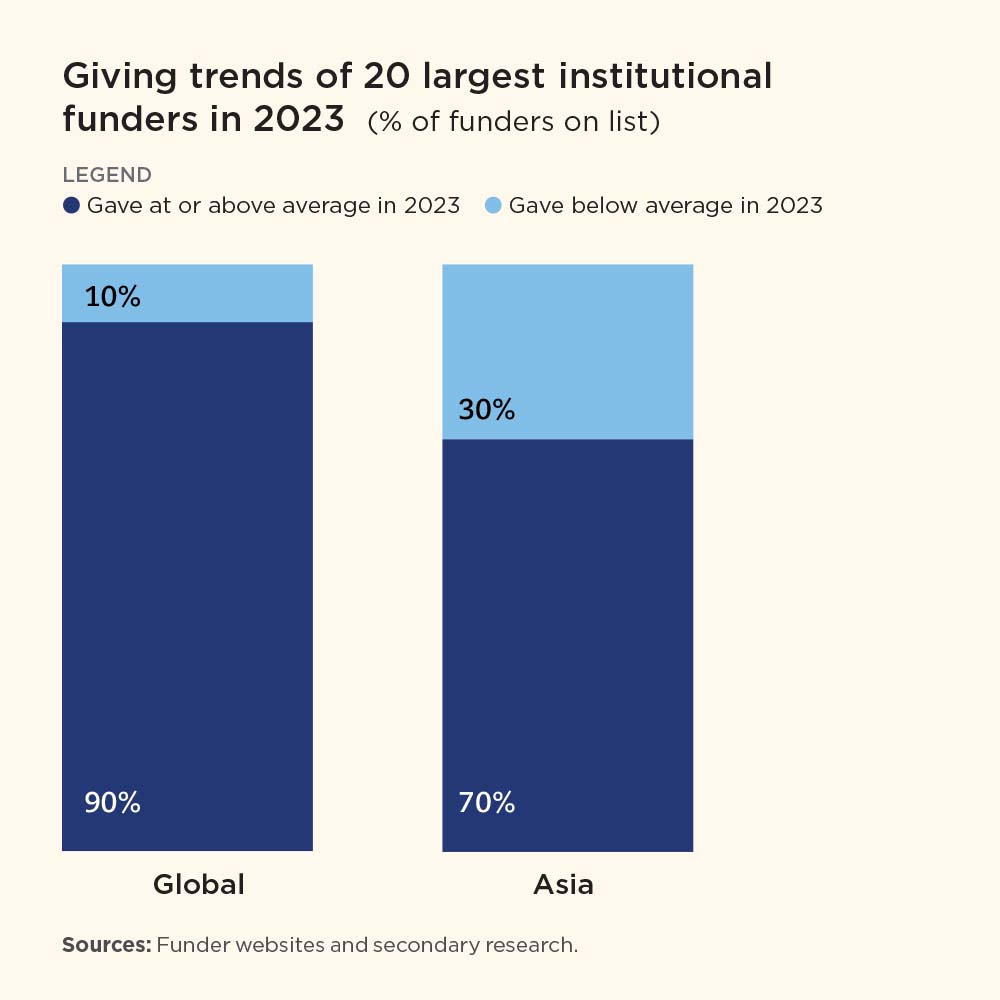

Ninety percent of global funders are giving more in 2023 than they have in the past, reflecting how giving is becoming increasingly concentrated, with a smaller number of donors (especially in the United States) accounting for a larger share of total giving. In Asia, only 70 percent gave more in 2023 than their five-year average which may reflect a pullback from higher giving levels during the COVID-19 pandemic.

These findings emerged from the second year of The Bridgespan Group’s ongoing research to identify the largest institutional philanthropies globally and in Asia. This article and its research was supported by our Funders Council – the Institute of Philanthropy, the Gates Foundation, and The Rockefeller Foundation.

Our first report detailed five practices that institutional philanthropies worldwide pursue to achieve high-impact results. This year, in addition to updating the list of the largest institutional funders, we are publishing a companion report that examines giving by corporations. They represent less than one-third of the largest institutional givers (most large institutional givers are not associated with corporations), but corporate givers are still a major source of philanthropic funding. The new report lists the largest corporate givers globally and in Asia, and it describes widely experienced considerations when giving and high-impact approaches to giving.

Methodology

Scope

We focused on institutional philanthropies that predominantly rely upon a single, private source of funds, including from an individual/family, a corporation, charity lotteries, or endowments. This excludes funders reliant on public fundraising, including donor-advised funds and community foundations. We also excluded state-linked institutions which (a) manage foreign aid or official development assistance and (b) are not philanthropic-focused organisations. The global list includes all countries; for Asia, we included countries that are part of the geographic region as defined by the United Nations. 5

Approach: Building the lists of the 20 largest institutional philanthropies

We determined the 20 largest institutional philanthropies based on the average of their annual giving over a five-year period from 2019 to 2023. For institutions with incomplete data, we assumed their giving was zero for the years where data was unavailable and took an average over five years.

We defined annual giving as charitable expenditures which include grants disbursed and expenses incurred for programmes operated directly by the institution. We excluded grants awarded or committed but not disbursed, as well as general operating expenses (e.g. administrative costs, depreciation, and all other costs not related to programme implementation). Where there was insufficient information to determine the purpose of the costs incurred, we excluded those numbers to avoid overestimating organisations’ annual giving.

To the extent possible, we relied on audited annual giving data from publicly available information, either annual reports or reports submitted to the government for compliance purposes. In addition, we requested information on annual giving from institutions known for their generosity but which do not publish data. These funders declined to share that information with us. Institutional philanthropies that do not publicly report expenditures were excluded, along with private giving not managed by a foundation and giving facilitated via corporate social responsibility (CSR) programmes.

We recognise that the annual giving reported for institutional funders likely underestimates the total giving from a source of wealth. Individuals, families, and corporations give through multiple avenues, including personal gifts, CSR, and corporate and/or private foundations. However, they might not publicly disclose all of their giving. After identifying the largest funders, we reached out to each of them to confirm their annual giving information. Not all institutions replied. We are grateful to those that did and were willing to confirm and/or clarify our numbers.