Last year was a remarkable year for large-scale giving by African donors. The continent’s philanthropic sector displayed unprecedented generosity and a strong commitment to helping Africa manage its fight against COVID-19.

The threat of COVID-19 on African lives and livelihoods was acute. As with other parts of the world, the pandemic risked healthcare systems being overrun. Globally, the public health crisis quickly became an economic one. In Africa in particular, the International Monetary Fund now estimates that economic growth in sub-Saharan Africa declined 2.6 percent in 2020[1] —the region’s first recession in 25 years.[2] As these threats mounted, African governments and philanthropists responded.

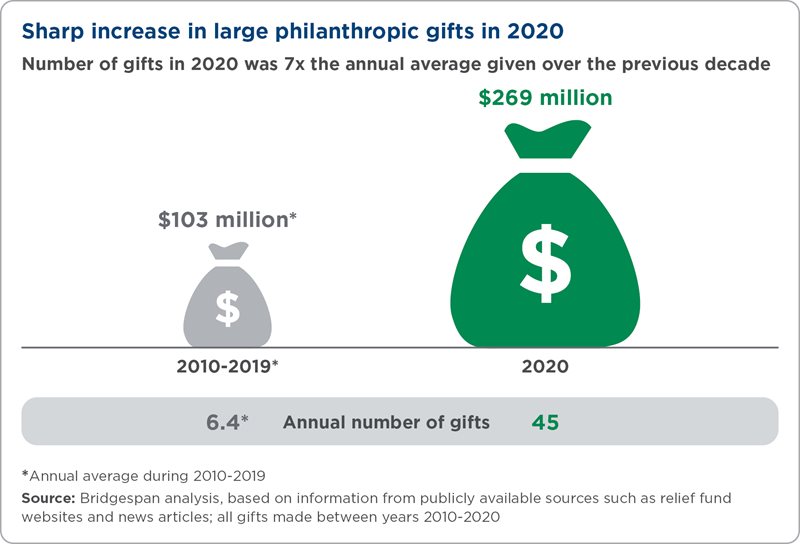

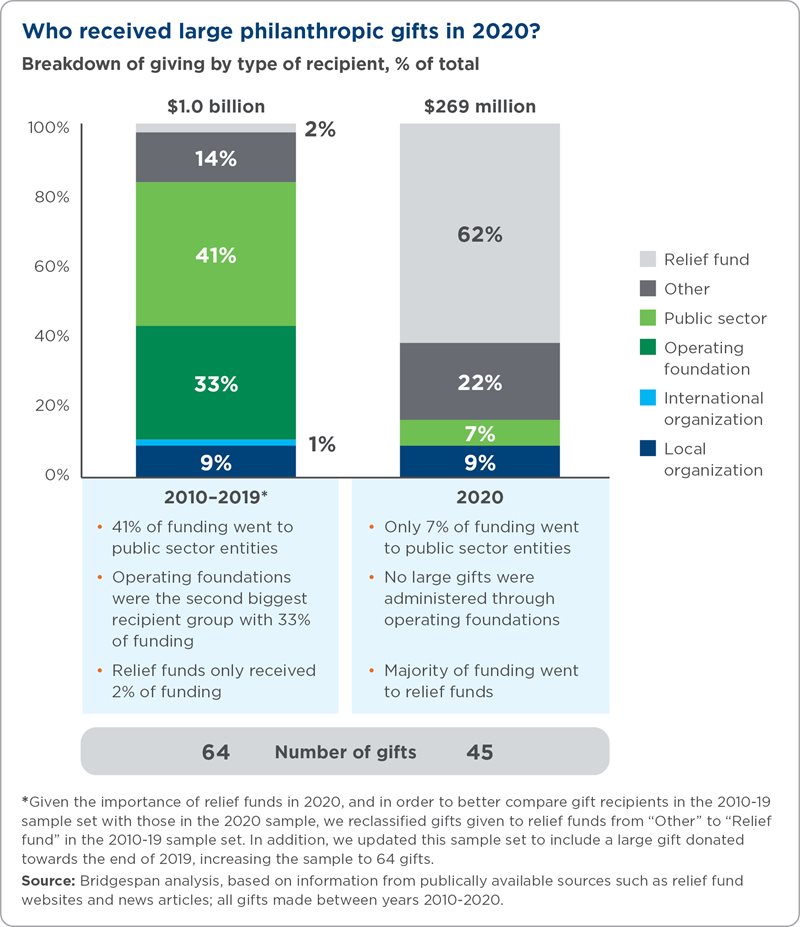

In our research at The Bridgespan Group, we found 45 large gifts, from March through December of 2020 in three countries, totalling roughly $269 million in value. This represents a sea change in the volume of African large-scale giving. In research that our Johannesburg- based team published in June 2020, we described the 64 “large gifts” (of $1 million or more) that we identified between 2010 and 2019,[3] from donors across five countries in sub-Saharan Africa, totalling over $1 billion.

In just one year, in response to a pandemic that threatened livelihoods across the continent, African philanthropists gave seven times the annual average number of large gifts for the previous decade.[4] No other disaster in the past 10 years attracted this magnitude of funding. The closest comparator is the Ebola outbreak in West Africa in 2014, for which we were able to identify six large gifts, totalling around $12 million.

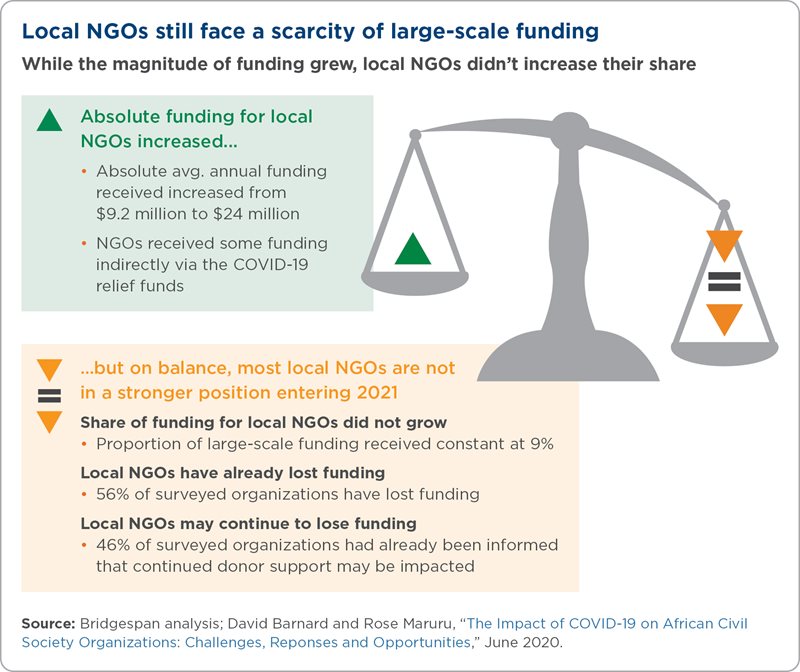

In 2020, African philanthropy responded to this crisis in new ways. And yet, we also saw some patterns persist. Giving was local, even while the virus was everywhere at once. And despite the outpouring of philanthropy, the continent’s local NGOs received less than one out of every 10 large gift dollars granted.[5] We think that raises questions worthy of further investigation.

The Rise of Relief Funds

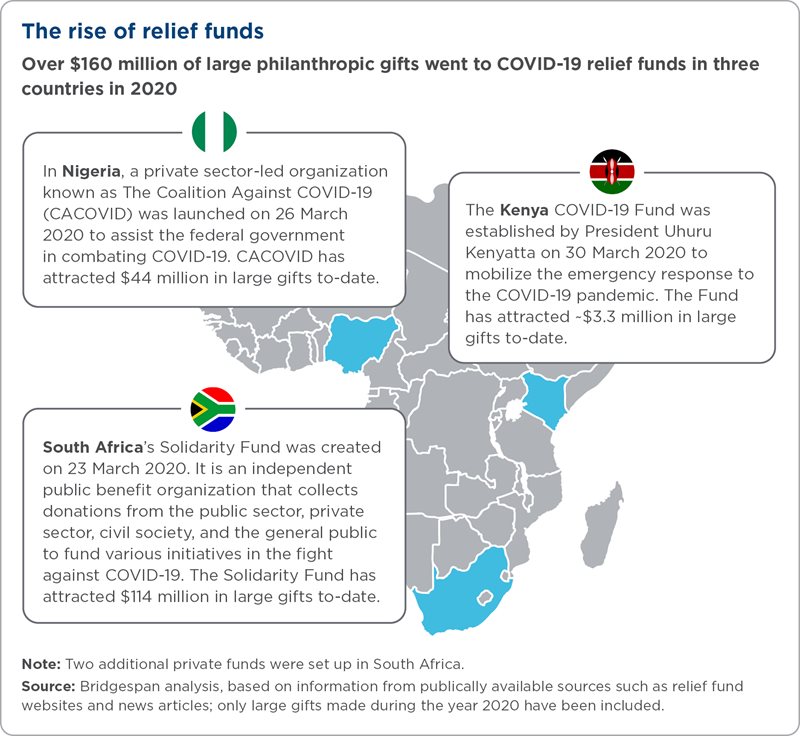

The first confirmed COVID-19 case in sub-Saharan Africa was reported on 27 February 2020 in Nigeria.[6] Within a month, South Africa, Nigeria, and Kenya set up specialized COVID-19 relief funds, which received 62 percent of the total dollar amount of large African gifts in 2020.

These relief funds are a relatively unique phenomenon for the continent. The only similar fund (i.e. a pooled collection of philanthropic resources earmarked specifically for crisis response) we found between 2010 and 2019 was the Africa Against Ebola Solidarity Trust Fund, created by the African Union in 2014 to mobilise resources to combat the outbreak in West Africa. That fund raised around $28.5 million in the fight against Ebola.[7]

A further $102.5 million last year was committed to respond to the pandemic outside of COVID-19 relief funds. In a break from past practice, only 7 percent of the funding went to either public sector institutions or operating foundations.

Giving Is Local…

From 2010 to 2019, 81 percent of the 64 large African gifts (by number of gifts) were given within a donor’s own country. Cross-border giving was mostly in response to disaster: of the 12 non-domestic gifts made between 2010 and 2019, eight were for crisis relief and disease eradication, such as Ebola response. However, in 2020, a year defined by disaster, 44 of the 45 gifts were domestic—the only exception was a gift by Nigeria’s United Bank for Africa to countries in which it has operations.

The domestic focus of the 2020 large gifts may be driven by the fact that, unlike previous disasters, COVID-19 affected every country on the continent rather than being concentrated in a particular region. As explained by Dr. Bhekinkosi Moyo, director of the Centre on African Philanthropy and Social Investment at Wits Business School in Johannesburg, “COVID affects everyone. It’s not like Ebola and the other [epidemics] that we have had in the past; those were geography-specific and, to some extent, community-specific.”

…But Not to Local NGOs

Although the amount of funding going directly to local organizations was significantly higher in 2020 in absolute terms, the proportion of total large-scale funding going to these organizations remained constant, at 9 percent. Local organizations received $24 million in large gifts in 2020 compared to the average annual amount of $9.2 million between 2010 and 2019. However, the $24 million comprised only two large gifts—a $13.3 million commitment from the ELMA Group of Foundations[8] to a range of South African organizations, and a $10.7 million donation from the Douw Steyn Family Trust and related entities to support local community organizations in South Africa.[9]

There are several reasons why local NGOs weren’t at the top of the list for large gifts to the pandemic response. For one thing, the relief funds were principally created to support government efforts to respond to the crisis, with a particular emphasis on healthcare infrastructure. For example, in South Africa, the worst affected country on the continent in terms of reported COVID-19 cases,[10] around 79 percent of that nation’s COVID-19 Solidarity Fund donations were allocated to the fund’s “health pillar,” which includes the manufacturing and provision of medical equipment to the country’s health department, ramping up COVID-19 testing capacity, and purchasing vaccines.[11]

Additionally, the leaders of these funds were predominantly from the private sector and government, with minimal representation from NGOs. African development expert David Barnard observed, “I don’t think nonprofits had a seat at the table in terms of the [COVID-19 response] strategy and planning; nor were they involved in terms of the actual delivery of services.” Finally, the strict national lockdowns across the continent resulted in some NGOs not being able to operate or having their operations curtailed, particularly in the face of technological constraints that made remote work challenging.

To be sure, local organizations did receive some funding indirectly via the COVID-19 relief funds, particularly as part of humanitarian response efforts. For example, in Nigeria, $74 million of CACOVID funding flowed to food relief programs run by both state governments and local organizations.[12] In South Africa, the Solidarity Fund tapped local organizations for food distribution and activities aimed at addressing gender-based violence during the national lockdown.

Notwithstanding the direct and indirect funding flows to local organizations in 2020, early research indicates that the effect of the COVID-19 crisis on local organizations has, on balance, been adverse. Between April 29 and May 15, 2020, @AfricanNGOs and EPIC- Africa conducted a survey of 1,015 civil society organizations (CSOs)[13] from 44 African countries about the impact of the pandemic on their funding and operations.[14] They found that 56 percent of the respondents had lost funding and half had already reduced costs. Meanwhile, 46 percent reported that some of their funders had informed them that COVID-19 might impact their ability to continue support.

The Future of African Philanthropy

The COVID-19 pandemic placed enormous strains on livelihoods in Africa, as it did the world over. Funders on the continent responded in unprecedented ways, not only with the amount of funding, but also by investing in new vehicles through which to direct much needed help. This could point to a new stage in the evolution of African philanthropy, one marked by a larger presence of local funders exploring new ways of achieving impact.

Still, for many African NGOs, the COVID-19 crisis has not only presented significant financial and operational challenges, but also exacerbated historical challenges related to funding constraints. This persistent funding pattern begs a number of questions that Bridgespan and the African Philanthropy Forum are currently engaging in a research effort to better understand:

- Why is a small share of funding flowing to African NGOs, even during a time of emergency?

- How do philanthropic funders—both African and non-African—currently think about funding African NGOs? Is there an aspiration to fund African NGOs more?

- What makes it difficult for funders to fund African NGOs today, and what is needed to facilitate more funding for them?

As we observed in our report last year, large-scale African philanthropy has distinct characteristics that don’t follow patterns observed in other regions of the world. That continued to be true in 2020. Time will tell whether the patterns that emerged in 2020 will be sustained, and whether there are learnings from the COVID-19 response that will help the sector further evolve in its own distinct way.

Jan Schwier is a partner at The Bridgespan Group and heads its Africa Initiative, based in Johannesburg. Maddie Holland is a case team leader at Bridgespan, where Soa Andrian is a consultant and Siyasanga Hayi-Charters is a senior associate consultant, all based in Johannesburg.

Methodology:

- To assemble and update the database, we used information from publicly available sources such as foundation websites and news articles.

- We selected $1 million as the threshold for grant size among African donors to be included in the sample.

- The sample only includes gifts from sub-Saharan African donors to causes or organizations in sub-Saharan Africa. We excluded gifts these donors had sent outside of Africa.

- We focused on gifts to “social change,” using a definition adapted from The Bridgespan Group’s “big bets” research in the United States.[15] Of note, our definition excludes gifts to arts institutions and religious causes, and includes gifts to academic institutions. We recognize that a substantial amount of giving in Africa, including from high-net-worth individuals, is channeled through religious institutions, such as churches and mosques, but these gifts are not included in the current analysis. The sample does include gifts to religiously motivated organizations, such as faith-based NGOs.

- We did not differentiate between individuals and their foundation when identifying grants. While research suggests that many donors make some gifts as individuals and others from their foundations, this distinction was often not clear enough in the source material (primarily news articles) to enable us to distinguish between giving vehicles on a gift-by-gift basis.

- We included in our database grants from corporate foundations, in addition to private funders, when the purpose of the gift fit our definition for social change. We recognize that a corporate entity’s motivations can sometimes be different from those of private philanthropists, but including corporate philanthropy allowed us to get a more complete view of the gifts African donors are directing towards social change on the continent.

- To determine the total amount of the gift in USD, we used the exchange rate from the month and year that the grant was made, and rounded numbers where appropriate.

- For the purposes of determining recipient types, we considered only the direct recipients of the gifts.

- We defined recipient types as follows:

- Local organization: Organizations that are headquartered in a country in Africa, including NGOs, CBOs and academic institutions. We recognize this is a very broad definition which does not capture the full nuance and complexity of what many feel it means to be a “local” African organization (e.g. does not take composition of leadership team into account). It is also not limited to organizations operating at a community level, and would also include Africa-headquartered NGOs operating nationally or regionally on the continent.

- International organization: Organizations founded and headquartered outside of Africa, including INGOs, foreign academic institutions, and multilaterals

- Operating foundation: A foundation that makes direct expenditures and implements its own programs rather than making grants to another organization

- Public sector: State or local government entities such as ministries, departments, public hospitals, and government relief programs, as well as private-public partnerships

- Relief fund: A pooled collection of philanthropic resources earmarked specifically for crisis response

- Other: Giving to social businesses (e.g. microfinance institutions), money pledged to particular uses where the ultimate recipient has not yet been identified (particularly special purpose funds), and gifts made to unspecified uses

- The recipient type Relief Fund was not included in the research brief that we published in June 2020. Instead, any gifts given to relief funds were classified as “Other.” We created this new recipient category due to the large number of gifts flowing to COVID-19 relief funds in 2020. For the purposes of this update brief, in order to better compare the 2010-19 sample set to the 2020 sample, we reclassified gifts given to relief funds from “Other” to “Relief Fund” in the 2010-19 sample set.

Footnotes

[1] “World Economic Outlook Update: Policy Support and Vaccines Expected to Lift Activity,” International Monetary Fund, January 2021.

[2] “World Bank Confirms Economic Downturn in Sub-Saharan Africa, Outlines Key Policies Needed for Recovery,” World Bank, October 8, 2020.

[3] Note that we updated this sample set to include a large gift donated towards the end of 2019, increasing the sample to 64 gifts.

[4] The number of gifts varied in a given year between 2 and 11.

[5] For the purposes of this research, we have broadly defined “local NGO” as any grantee organization headquartered in an African country. We recognize this definition does not capture the full nuance and complexity of what many feel are important characteristics of an “African” organization, e.g. it does not account for leadership team, governance structure, etc. This definition is also not limited to organizations working at a community level, as it also includes Africa-headquartered NGOs operating nationally or regionally on the continent.

[6] Ruth Olurounbi and Alonso Soto, “Nigeria Tracing First Coronavirus Case in Sub-Saharan Africa,” Bloomberg, February 28, 2020.

[7] Roughly $5 million of the large gifts that we tracked went to this fund. “Ebola outbreak: Africa sets up $28.5m crisis fund,” BBC News, November 8, 2014.

[8] It should be noted that only part of this commitment was made by ELMA South Africa Foundation (the only

entity in the Group we have classified as an ‘African funder’) and that only two organizations, DG Murray

Trust and SAMRC, received commitments of $1 million or more. However, due to a lack of publicly available

information on the exact details of the commitment, we have included the full sum of the commitment in

our dataset. While we recognize that this introduces a level of imprecision in our sample of gifts, we felt it

important to acknowledge the ELMA commitments, given the Group’s roots in/connection to the African

continent. Outside of the commitments included in our dataset, The ELMA Community Grants Program

provided emergency support grants to its portfolio of community-based organizations on the continent.

Source: “ELMA Commits ZAR2 Billion to COVID-19,” ELMA website.

[9] The Douw Steyn Family Trust and related entities donated funds to unspecified NGOs and NPOs running feeding schemes in communities around Steyn City, Johannesburg, South Africa: “TIH’s COVID-19 Relief Fund.” We assumed that these are local organizations given their community focus.

[10] John Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center, as of January 1, 2021.

[11] Based on allocated funding as of January 5, 2021.

[12] This compares to $34 million of CACOVID funding directed towards medical facilities and equipment: Babajide Komolafe, “CACOVID: Much needed succour for a challenged nation,” Vanguard, January 1, 2021.

[13] This term includes NGOs, NPOs and community-based organizations.

[14] David Barnard and Rose Maruru, “The Impact of COVID-19 on African Civil Society Organizations: Challenges, Responses and Opportunities,” June 2020.

[15] William Foster, Gail Perreault, Alison Powell, and Chris Addy, “Making Big Bets for Social Change,” Stanford Social Innovation Review, Winter 2016.