Election years tend to heighten a nonprofit’s sense of uncertainty, especially for those whose work is front and center in current policy and government funding debates. Some election outcomes may herald new opportunities and pressures to drive progress, while others could signal a need to protect hard-won victories and prevent backsliding. Preparing for such starkly different visions of the future can be daunting.

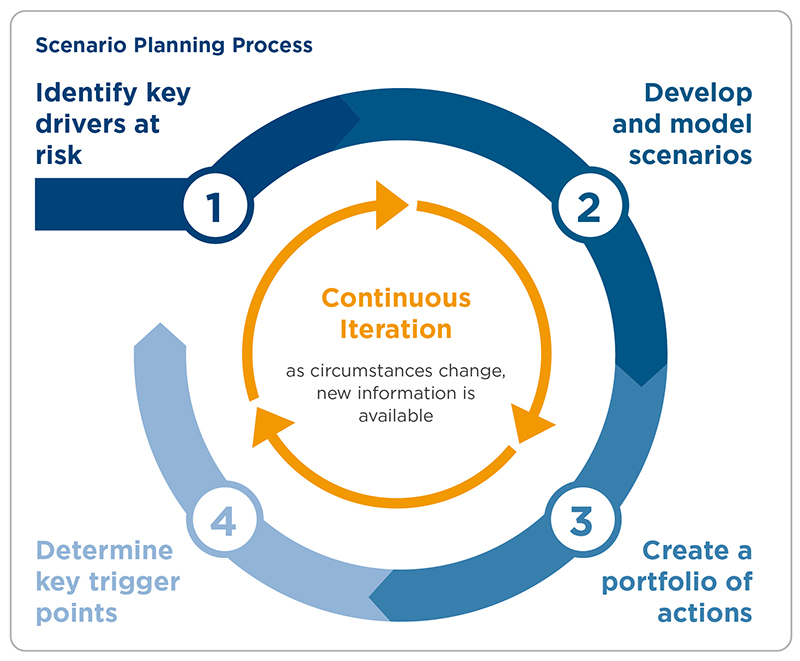

Building scenario plans can help by giving leaders a structured approach to preparing for potential futures. The Bridgespan Group has helped a variety of nonprofit organizations use scenario planning. We’ve drawn on that experience in this article to revisit our scenario planning toolkit, consider what nonprofits in the United States can do now to prepare for different election outcomes, and share lessons and reflections from organizations that have done scenario planning.

Before we dive in, we’ll share the advice of one interviewee who encouraged peers to “take a deep breath.”

Thinking about change can be stressful—especially when the change is outside one’s control. But it is possible to plan for it, if you take a measured, stepwise approach to scenario planning.

It’s also helpful to remember that “we got through previous election cycles, and we will get through this one together, too,” says Angel Padilla, an interviewee we spoke with about his organization’s recent scenario planning work. Padilla is vice president for strategy and policy at the National Women’s Law Center (NWLC), a nonprofit that fights for gender justice through policy, research, litigation, and narrative change work. In fact, part of the value of effective scenario planning is taking the worry we carry around in the back of our minds and wrestling with it head-on, so we can prepare effectively for each scenario and know that there is a path forward in either situation.

Prework: Refer to Your North Star

Scenario planning is all about how to navigate uncertainty so unexpected events don’t throw the organization off course. To stay on the right track, first remind yourself of the long-term goals you’ve set for the organization, whether it’s a 10-year vision or a clearly defined intended impact and theory of change. Regularly referring back to this “North Star” can help leadership teams take the long view—even through short-term disruption—and ground your decisions and communications in a shared language around the organization’s most important goals, principles, and vision for the future.

If you are considering scenario planning exercises now, or as the election approaches, we recommend re-sharing the North Star with your organization, as well as any guiding principles for decision making. With this information, staff have greater visibility into how decisions and actions (especially any tough changes) connect to the long-term goals they know and care about. (See “A Compass for the Crisis: Nonprofit Decision Making in the COVID-19 Pandemic” for an example of decision-making principles nonprofit leaders frequently used when navigating tough trade-offs during the COVID-19 pandemic.) If you haven’t already aligned on guiding principles, you’ll want do to so before embarking on the four-step scenario planning process outlined below.

Step 1: Identify Key Drivers at Risk

Every organization has a small set of factors that drives its ability to achieve impact and sustain the organization. These factors, or drivers, might relate to the demand for services or expertise, the capacity to do the work itself (which might be more difficult in certain environments), costs, or the ability to generate revenue and support. With the North Star in mind, nonprofits can start scenario planning by identifying the key drivers that are likely to shift most depending on how the future unfolds.

Alder Graduate School of Education is an affordable, one-year teacher residency program that works in partnership with public K-12 school systems and charter management organizations to recruit and train teachers who are more effective in the classroom, are more representative of their communities, and remain in the teaching profession for longer than their peers. The Alder team participated in Bridgespan’s Leadership Accelerator program on Creating an Adaptive Plan in 2023 with the specific goal of considering how different policy environments might affect their work.

Two related drivers at risk for Alder were funding (the possibility that the state funding that reduces tuition costs for teacher candidates would not be renewed) and enrollment (without state funding, potential candidates interested in the program might hold off on applying). “The funding cliff is out there,” explains Alex Caram, managing director of strategy and partnerships. “And we are trying to figure out all the possible moves to either shift the policy or to shift behaviors so that candidates and K-12 school systems can pay for what used to be free.”

Step 2: Develop and Model Scenarios

Using the most important drivers at risk, the next step is to identify what would happen to each of those drivers under a shortlist of scenarios. These scenarios might correspond to different federal, state, or local electoral outcomes, along with other potential shifts in your environment. When identifying potential scenarios, don’t reinvent the wheel if you don’t need to: you may be able to find field resources with analyses of potential election outcomes or broader trends (for example, see this report on future scenarios for climate action, from Deloitte). From there, you can think through the potential impact on the drivers you prioritized in Step 1.

The National Domestic Workers Alliance (NDWA) is a national federation of grassroots organizations and a national membership organization engaged in organizing workers and voters, shifting public narratives, and changing policies to advance the respect and rights of domestic workers in the United States. Before the 2016 election, NDWA held scenario planning workshops for its staff and board to think through how the federal policy environment might change based on different election results.

NDWA also used the workshops to consider its newer private sector activities. The tech boom in the 2010s had started to shift the domestic care economy, including how households find and interact with domestic workers. “Part of our goal was to consider the openings and opportunities in the private sector within the different electoral scenarios,” says Mariana Viturro, NDWA’s deputy director.

To do that, the workshops assigned participants one of five scenarios representing different combinations of four political and economic factors that could affect NDWA’s work: which candidate won the presidency, which party won control of Congress, trends in the tech sector, and trends for unions. This set them up nicely for Step 3 of the process, determining how they might respond within each scenario.

Step 3: Create a Portfolio of Actions

Once you have a shortlist of scenarios, you can begin to tackle the question that’s been nagging you all along: how will we respond? We recommend creating a portfolio of actions you may consider taking under each scenario. Some of these actions may be reactive, for example, how to respond to policy or funding changes. Others may be proactive, such as how to explore or pursue new opportunities. Consider three types of actions: “no regrets” actions that are appropriate for any scenario; smaller-scale and more flexible actions that can be tested, implemented, or reversed quickly; and larger and more permanent actions to implement once it is clear they are needed.

Recognizing the importance of supportive state policies and funding for its teacher residency program, the “no regrets” actions Alder identified in 2023 included hiring a policy advisor and joining coalitions that could amplify its message to state policymakers. “Every few years, there will be an election cycle where some of your champions are going to leave. You have to keep investing in order to build and maintain relationships, stay relevant and helpful to policymakers, and be able to move quickly when the moment strikes,” says Caram.

In NDWA’s scenario planning workshops, participants considered a hypothetical case study, created by the workshop organizers in NDWA’s innovations team, about what the political and economic scenarios would mean for its work engaging the tech sector. Discussion questions included the following: What must NDWA be great at in this future, and how can we prepare? How important is our private sector strategy in this reality? What type of engagement do we want to take on?

“We wanted more direction for our private sector strategy, and for our staff and board to think about their appetite for this work, and the parameters for what we’re willing to entertain given potential scenarios,” Viturro explains. She emphasized that understanding where people are and aren’t willing to negotiate under different circumstances (especially when their power and leverage has changed) is an important byproduct of scenario planning. For NDWA, confronting potential changes in its ability to influence federal policy before the 2016 election was the right moment to think about other goals and opportunities for the organization.

Keep in mind that even the best-case scenario (such as the election of a candidate with aligned policy preferences) will come with its own pressures and challenges, while the worst-case scenario may bring unexpected opportunities. For example, some nonprofits may find they receive more funding and better alignment with partners in the latter scenario. “In some ways, it’s easier to hold coalitions together and focus on what matters most when you’re fighting back,” says Padilla from the NWLC.

Step 4: Monitor Trigger Points

You now have a portfolio of actions. But which will you ultimately implement, and when? The final step is to identify trigger points that will spur a decision to act. The election itself is a clear trigger point, and others may happen before or after. For each of your key drivers, you might brainstorm the indicators to monitor. For example, a percentage change in participants or partnerships might indicate a shift in demand for your services, and a policy change might affect what services you can deliver or the amount of funding available.

In the case of Alder, scenario planning prompted the team to start monitoring the budget for the Golden State Teacher Grant, a one-time block grant scoped to last until 2026. “We know firsthand how impactful this funding is for our prospective candidates, so we started poking around to ask, ‘How much money is left? What’s the runway?’” Caram says. “And when we did that, our contacts in government didn’t have a straightforward answer for us. So, they did the accounting. This nudge helped the whole field learn the funds were going to run out a year earlier than expected.” Its monitoring helped Alder start conversations and take action to renew the funds before they elapsed, avoiding the actions in the worst-case scenario the team had identified.

Whom to Involve, and How

You have a choice about the level of depth and rigor you aim for in your scenario planning, from a one-day exercise with your leadership team to a one-month project taking advantage of wider expertise and data sources. That choice may depend on your size, the extent of impact you anticipate from the election, and how much information or capacity you have to begin planning effective responses.

No matter what, you’ll want to think about whom to involve in each step of scenario planning to make the best use of your resources. For the NWLC, that meant mapping out the high-level scenarios with their senior leadership team during a retreat and then building out portfolios of actions with the teams that would be most affected. To make that latter step very practical, in the coming months teams will discuss the strategies they would pursue under each of the scenarios and the concrete deliverables they might want to put together for each one.

For NDWA, engaging the entire staff from the beginning was important. “We have a whole organizing team engaging workers, and an affiliate team engaging with affiliate members, so they need to tell us what they’re hearing,” explains NDWA’s Senior Director of Policy and Advocacy Haeyoung Yoon.

Scenario planning is also an opportunity to get board members and funding partners involved before the going gets tough. When the NWLC team presented plans to its board, they thought members might urge caution. Instead, the board recognized the organization had a window of opportunity in front of them.

Nancy Withbroe, NWLC’s chief of staff, recalls one board member saying, “This is not the time to be saving for the future: it’s go-time right now.” “It was so helpful to hear that message from the board,” she says. “This is the framing boards should have right now, and the scenario planning really helped everyone get in that right mindset.”

Taking a Field-level View

While the examples above describe scenario planning undertaken by individual organizations, it can also be valuable to work with partners to create a shared understanding of what’s coming—and plan how to collaborate. Recognizing that political changes impact entire fields within the social sector, not just individual organizations, the nonprofit Future Currents (formerly the Social and Economic Justice Leaders Project) offers scenario planning workshops in which organizations in a coalition or movement participate together.

“Sometimes it’s a set of similar organizations who want to figure out how to relate to each other. Other times the organizations are building a shared strategy together and identifying each of their roles,” says Executive Director Connie Razza. This year, Future Currents is helping movements to look ahead to the potential governing, policy, and cultural environments the election could bring about, and to identify the movement infrastructure, capacity, and relationships needed, as well as what each organization can own versus what they do together.

People’s Action, a network of 42 member-based organizations in 30 states, builds the power of poor and working people to win change through issue campaigns and elections. Executive Director Sulma Arias recently participated in a Future Currents workshop with other leaders of national networks. Like Razza, Arias emphasizes that the political scenarios they are anticipating would bring challenges for the whole field, not just one organization. According to Arias, nonprofit and movement leaders need to overcome the culture of competition and create a community—to share lessons on how to respond if one organization faces a legal challenge, for example, or to identify whether there’s a field-level response, rather than every organization acting on its own.

* * *

Once again, take a deep breath. Whatever level of detail is right for your organization, scenario planning still takes dedicated time and attention, as well as mental and emotional energy—though so does worrying about the future without preparing for it.

“The mental heaviness can paralyze you,” says Arias from People’s Action. “You need to maintain hope and see the potential opportunities, not just the uncertainty and chaos. Otherwise, your productivity will be stifled by the number of things to worry about.”