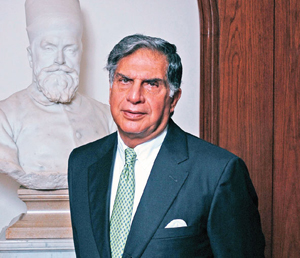

Ratan Tata is one of India’s most prominent business and philanthropic leaders. He headed the Tata Group, a Mumbai-based global conglomerate with family roots extending to the 19th century, from 1991 to 2012, when he stepped down to become chairman of Tata Trusts. The Tata founders bequeathed most of their personal wealth to the many trusts they created for the greater good of India and its people. Today, the Tata Trusts control 66 percent of the shares of Tata Sons, the Tata holding company. Ratan Tata earned a bachelor of architecture degree from Cornell University in 1962 and began his career with the Tata Group on the shop floor of Telco (now Tata Motors, which owns Jaguar and Land Rover) and Tata Steel, where he shoveled limestone and was a team member in the blast furnaces. In the following conversation, Ratan Tata talks about his approach to philanthropy with Rohit Menezes and Soumitra Pandey, partners at The Bridgespan Group.

Rohit Menezes and Soumitra Pandey:

What were some of the experiences that have informed your approach to philanthropy?

Ratan Tata: Working on the shop floor as a young man, I saw close up the misery and hardship of the less fortunate and thought about how one makes a difference to improve lives. As I moved up through departments and divisions, I continued to see hardship and had more opportunity to do something about it. Now I’m trying to take the Tata Trusts to a different level of relevance in the 21st century to maximize the benefits the trusts seek to bring to disadvantaged communities.

Do you have a philosophy of philanthropy?

If I put it into one sentence, I think you really want to be doing things that make a difference. If you cannot make a difference, it’s just water trickling through a tap or leaking through a drainage system; it’s wasteful. Dr. [Jonas] Salk must have had a tremendous feeling of satisfaction when he developed the polio vaccine. Similarly, I think going after causes where you make a difference, rather than scratch the surface, is very much in keeping with the trend in new philanthropic endeavors.

What changes have you made in the trusts’ operations, and what do you aspire for them to become?

A fair amount of our early philanthropy was in the form of charity to alleviate individual hardships—helping people with money for dialysis or for surgery, for example. And we worked with a lot of NGOs, supporting them with grants. We’ll continue to help alleviate individual hardships and support NGOs, but we also want to be more involved and to manage projects ourselves. We want to enhance our impact and ensure that interventions are sustainable. The question is: Can we fund a research project that aims to eliminate or control a certain disease and, therefore, has the potential to benefit a larger number of people, or should we stick with helping individuals suffering from that disease? We believe we can make a greater difference through large projects that serve mankind.

Can you give us some examples?

One of the big changes has been in how we are combating malnutrition. We lose so many children in India at infancy or within the first two years because of malnutrition. This led us to embark on a program of providing nutrients to infants. But it took only a few weeks of research to realize that we couldn’t do that without involving the mother, who was also malnourished. We also found out very fast that we couldn’t accomplish our goals unless we addressed hygiene and sanitation. Education also got included in our program.

We focused our efforts at the village level, and our approach became holistic, which attracted other philanthropic organizations. We’ve also received tremendous support from the state governments where we were working. This is an example of the kind of transformation to direct involvement we are trying to achieve in our work for agriculture reforms, water conservation, water purification, and education.

The Saathi Internet program is an example of the trusts teaming up with a corporation. (See “Case Study: Saathi.”) We’re working with Google to help rural women understand the Internet and give them a means of securing a livelihood. It’s a new model of philanthropy for the trusts and not the kind of project we would have gotten into earlier. And we are working with the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation to tackle diarrhea. This is a first for the Gates Foundation, which had previously always executed such programs by itself.

So the trusts have shifted emphasis from charity to projects with sustainable impact?

I have been emphasizing that the trusts must be concerned about the sustainability of the communities where they work. Until recently, we would support an NGO for 8 or 10 years, and then want to move those funds to another community. We would assume that this community was now self-sustaining, but it wasn’t. So when we withdrew our funds, the NGO collapsed, the village programs collapsed, and we became the most hated organization in the village. So, sustainability is a new calling for the trusts.

Do you consider program costs when evaluating grants?

Yes, at all times. The greatest challenge one has in working with NGOs is finding those that are well organized and not just a well-intentioned entity run by a bunch of society people. Those sorts of people often run something badly, have little or no financial discipline, and think they are doing a great thing when they are actually wasting resources.

In recent years, we have asked for grants back when NGOs haven’t performed as they promised. This has added to our cost because it involves a fair amount of auditing and visiting and evaluating progress. It has also given us a great feel for which NGOs can be turned around by assisting them and those that can’t. In which case, they get their funds from somewhere else, not from us.

What advice would you offer to other philanthropists who seek to blend charity with strategic philanthropy?

My advice is to do thorough research before deciding where to get involved. A lot of money is less effectively used than it could be because an organization has not done enough research. Today, a large amount of philanthropy in India is deployed in traditional forms like building a temple or a hospital. India has to move into a more sophisticated form of philanthropy that is designed to make a difference rather than just building edifices.

Do you encourage your grantees to partner with government agencies?

There is a tremendous need for NGOs and philanthropic organizations to consider partnering with government agencies. Unfortunately, there has been a view that the government shuns collaborating with NGOs or philanthropic groups because officials consider the so-called welfare of the people to be their business. But our own experience in working with state governments has been very positive. We have terrific cooperation, and without the infrastructure that government agencies have built, we could never have achieved the impact we have today.

Is it difficult for you to find NGOs ready to take on strategic partnerships?

Very often an NGO ignores or forgets the traditional outlooks of the community they are working in, and because of that, what they are trying to do, however well-intentioned, doesn’t work. Also, corruption and collusion can divert resources to personal use. For example, about five years ago we were funding 10 schools through an NGO in Bihar. On one of our site visits, we found that the principals and teachers were coming to school and signing in, then leaving the children unattended. The children played all day, and their parents didn’t even know. The students never got an education. But the principals and teachers got paid. To make matters worse, the government was paying for midday meals, but the kids never got fed. The money was divided between the principals and the teachers. So we stopped giving grants to those 10 schools. Who suffered? The kids suffered, and we were the nasty people who stopped the grant. But what could we do? A lot of that goes on.

And now with the requirement that large companies in India devote 2 percent of profits to CSR [corporate social responsibility], a whole bunch of NGOs have lined up to receive these funds. What we will need to do is to see how much of this is well spent and how much just gets short-circuited.

Are you worried that much of the CSR money will not be used well?

There could be a fair amount of abuse of these funds, and the government will have to do some regulation to make sure that the money is used effectively. It would not be a bad thing if the government designated a number of causes to which companies could give these funds. Even large public works projects could be funded this way. The government may have to define what the projects are and be ready to ensure oversight.

Are Indian companies prepared to implement the CSR mandate in a way that will make a difference?

I think many CEOs would say that they are doing it because it is required. But if we can get even a small number committed to make a difference, I think we will get projects that will be showcases of what one can do with such funds. CSR could become an avenue for innovative thinking of how you can improve the quality of life of the people of India, or it could be wasted.