We are in a pivotal moment for technology in the social sector. The emergence of artificial intelligence (AI) is reshaping how organizations think about the tools, talent, and infrastructure needed to deliver impact. Nearly two-thirds of nonprofits report using AI—mostly for communications, productivity, and fundraising. Ninety percent say they want to deepen their adoption, underscoring both the enthusiasm and the urgency for investment.

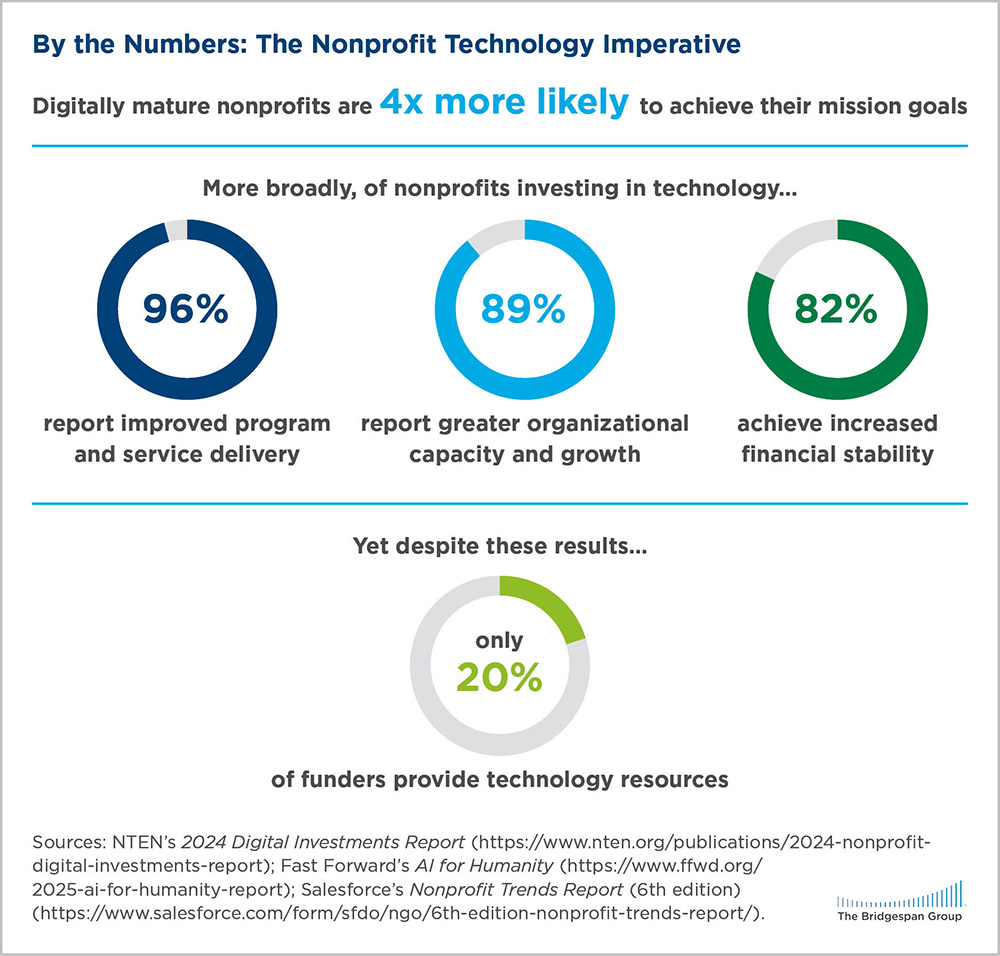

Beyond just AI, the evidence in support of tech spending is compelling. Ninety-six percent of nonprofits that invest in technology improve program and service delivery, 89 percent experience increased organizational capacity and growth, and 82 percent achieve greater financial stability, according to NTEN, a nonprofit tech advocate. “[Technology] is a mission enabler that facilitates nonprofits’ ability to achieve greater impact, generate efficiencies, and deepen engagement with their constituents,” wrote Jean Westrick, executive director of the Technology Association of Grantmakers (TAG).

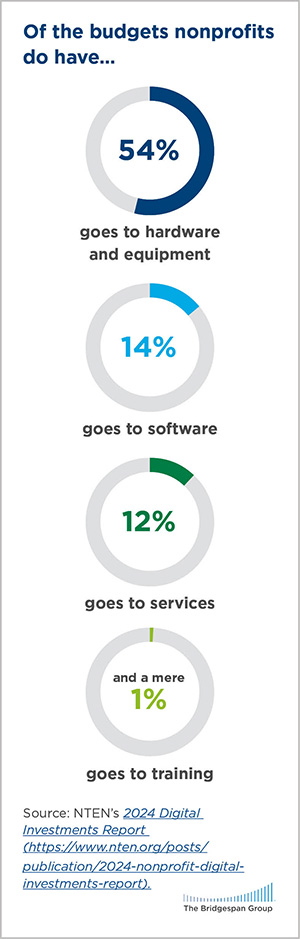

Yet funding still lags. Only 20 percent of funders currently provide grantees with money for technology tools and resources. Moreover, NTEN’s 2024 Digital Investment Report found that just 11 percent of nonprofits say foundation grants contribute significantly to their technology budgets. Of the budgets nonprofits do have, 54 percent goes to hardware and equipment, compared with just 14 percent for software, 12 percent for services, and 1 percent for training. In other words, hardware eats up most of the tech budget while the enablers of transformation (software, integration, staffing, and training) remain severely underfunded.

Yet funding still lags. Only 20 percent of funders currently provide grantees with money for technology tools and resources. Moreover, NTEN’s 2024 Digital Investment Report found that just 11 percent of nonprofits say foundation grants contribute significantly to their technology budgets. Of the budgets nonprofits do have, 54 percent goes to hardware and equipment, compared with just 14 percent for software, 12 percent for services, and 1 percent for training. In other words, hardware eats up most of the tech budget while the enablers of transformation (software, integration, staffing, and training) remain severely underfunded.

This pattern can trap nonprofits in a cycle of outdated or fragmented systems. To save costs, they may patch together donated or low-cost systems without the expertise or support to maintain or integrate them. While ad hoc solutions can deliver short-term results, they rarely scale with an organization’s needs, leading to inefficient workflows, siloed data, and limited digital capacity.

However, the landscape is shifting. AI and other emerging technologies, such as low-code/no-code solutions that make it possible for nontechnical teams to design and deploy digital products, are creating new opportunities for impact. And these are not hypothetical. Fast Forward’s AI for Humanity report highlights nonprofits that have already achieved dramatic gains, from quadrupling annual translation capacity to reducing end user response times by more than 75 percent. And the emergence of increasingly competent AI agents over the next months and years promises only to accelerate the pace of change.

In The Bridgespan Group’s work with more than a dozen nonprofits over the past 18 months, we’ve seen these dynamics play out repeatedly. Organizations are eager to modernize, but funding gaps keep meaningful progress out of reach. These experiences reinforce what the data show: technology succeeds only when it is resourced as part of an organization’s core infrastructure, not treated as a side project or discretionary expense.

The Pay-What-It-Takes Approach: Valuing Tech as a Core Operating Cost

At Bridgespan, our work on “Pay-What-It-Takes” philanthropy has consistently highlighted the chronic underfunding of nonprofit operating costs, from staff development to essential infrastructure. Technology is no exception. Despite being critical to scale, efficiency, and impact, it is still often treated as a “nice-to-have” rather than a necessity.

By contrast, tech spending is critical for the private sector where money is allocated for a full range of costs. Forrester estimates that personnel costs account for 35 percent of enterprise IT budgets, while software represents 21 percent, with the remainder divided across hardware, infrastructure, and external services.

This data reveals a consistent pattern: business technology budgets emphasize people, software, and integration capabilities as key enablers of transformation. While the operating costs of nonprofits differ from the private sector, just over half their limited tech resources go to maintaining physical assets. Yet they are still expected to achieve digital transformation without the sustained investment in leadership, talent, and systems that make it possible.

This mismatch shows up every day. One education nonprofit we heard from received a large grant to build tutoring software that would dramatically expand its virtual reach. The software was a success, but the executive director later confided that they were scrambling to fundraise for the infrastructure to keep it running. Similarly, a program manager at another nonprofit, reflecting on a $1 million grant to implement a consolidated Salesforce database, a system used to store and manage data, admitted that a year later, he’s “not sure anyone even knows how to use it anymore.”

These examples highlight a common issue: what’s missing is not only funding for systems, but also funding for people. When only one percent of nonprofit tech budgets go to training, the sector lacks the capacity to sustain new tools. Funders who support training and talent alongside technology (e.g., tech capacity grants, AI literacy training, and unrestricted funding) can turn one-off pilots into drivers of long-term impact.

Five Actions Funders Can Take to Close Nonprofits’ Technological Gaps

1. Listen to Nonprofit Partners and Support Reflection

In our work, we have seen that the most effective funder-grantee conversations begin not with a solution, but with genuine curiosity. The Center for Effective Philanthropy’s grantee perception reports, as well as other mechanisms, create an opportunity for deeper listening and sensemaking. The goal is to understand where a nonprofit is on its technology journey, as well as its aspirations, constraints, and readiness, and to align support accordingly.

This means listening for different signals:

- Some organizations may already have a clear technology strategy or roadmap but struggle to find funders willing to resource “overhead” costs such as staffing, integration, or training.

- Others may know they need to modernize but lack clarity on how technology aligns with their mission or where to start. In those cases, funders can support a process to help leaders reflect and plan before investing in any tools.

Funders can play a catalytic role by giving grantees both the time and the means to connect digital investments to their core work, whether through planning grants, technical advisory support, or peer learning opportunities. What matters most is not prescribing the process, but ensuring nonprofits have the flexibility and support to define what they truly need.

Sector barriers like cost, limited internal capacity, lack of expertise, and uncertainty about where to begin are well documented. Approaching early conversations with curiosity, not conclusions, helps uncover real needs and root causes, leading to opportunities for more tailored and sustainable support. Some nonprofits may benefit from a technology and data audit to establish a baseline understanding that, with funder support, can guide right-sized solutions and investments over time.

However, this opportunity is often missed. The Center for Effective Philanthropy’s AI With Purpose report found that three-quarters of nonprofits believe funders have little to no understanding of their AI-related needs, and fewer than 20 percent have ever discussed AI with funders. A recent report from Project Evident reinforces the lack of understanding and discussion, reflecting a gap not in intent, but in capacity and engagement.

Three questions can help guide early reflection and dialogue (and if you don’t know where to start, feel free to refer to our previous Bridgespan article for example use cases and question prompts):

- In what ways could technology enable new approaches or accelerate progress toward your mission? And in what ways can technology (along with other non-tech supports) solve pain points to delivering on your mission at scale?

- What technology investments are critical to achieving sustained, mission-aligned impact?

- What barriers (technical, financial, cultural, or organizational) could hinder adoption, and how might they be addressed?

2. Understand Real Costs for Nonprofits

Technology budgets often focus narrowly on hardware, licenses, or initial implementations. But the real costs are broader and ongoing. This is especially true with AI. Fast Forward found that 48 percent of AI-powered nonprofits report higher technology-related expenses after adopting AI, and 84 percent say additional funding is essential to sustain development, largely because AI tools require ongoing training, data management, and integration support.

By defining technology cost drivers, funders can better understand and align with their grantees’ ongoing needs. These costs typically fall into four categories that include both core technical systems and the ancillary supports (training, personnel) needed to make them work effectively:

- Acquisition: Up-front costs of infrastructure (hardware, cloud storage, cybersecurity, compliance, etc.) and systems/tools (CRMs, financial systems, AI applications, etc.). These expenses extend beyond licenses to customization and integration.

- Implementation: The costs of configuring tools, integrating with workflows, and managing change. This includes vendor services, internal staff time, and training to ensure effective adoption.

- Operations: Ongoing maintenance, troubleshooting, upgrades, and continuous training and adaptation as the organization grows. These recurring costs ensure systems remain reliable, secure, and aligned with evolving needs.

- Shared Learning and Experimentation: Collaboration is already emerging as a hallmark of innovative nonprofits. Fast Forward found that 43 percent of AI-powered organizations open-source their tools, meaning the source code is publicly available, allowing anyone to use, modify, and distribute it. Investing in and supporting shared platforms and knowledge exchange multiplies the impact of each investment and avoids duplication.

It’s worth noting that size and flexibility matter. A grassroots organization with a $500,000 budget faces different costs than one with a $10 million budget. In-kind contributions, such as “free” credits or licenses, should be carefully factored into real costs since these supports can shift suddenly. Product companies may begin with generous intentions, but market realities can quickly change. We have seen this play out when providers such as Microsoft and DoorDash, which supported hundreds of nonprofits with delivery tools during the pandemic, later moved to paid models, creating significant and unexpected budget pressures.

3. Fund for the Long Haul

The reality is that technology isn’t a one-time expense. The Center for Effective Philanthropy reports that nearly 90 percent of foundations provide no AI implementation support, and fewer than 15 percent plan to increase this in the next three years. Fast Forward highlights the consequence: without unrestricted, upfront funding for integration, iteration, experimentation, and capacity-building, even the most promising solutions stall.

Funders can address this with flexible, multiyear, unrestricted funding that covers the full lifecycle of adoption. But just as important is how technology projects are scoped. Too often, statements of work (SOWs) emphasize tool delivery over long-term adoption. Effective SOWs are co-developed with nonprofits to define needs, implementation plans, and adoption supports with clear accountabilities, including training and continued vendor support for a set period after launch.

Investing in tech talent varies by stage. For some nonprofits, the first step may be hiring an IT specialist or data analyst to provide day-to-day support. For others, it may mean creating leadership roles like chief technology officer or adding product managers to bridge strategy and delivery. As organizations scale, roles like data architects, engineers, cyber security leads, and AI specialists become critical.

Competition for this kind of talent is fierce, and salaries for experienced professionals often far exceed traditional nonprofit compensation bands. Funders can prepare for this reality by supporting grantees in budgeting accordingly, whether through flexible funding, salary benchmarking, or shared staffing models. What matters is enabling nonprofits to attract and retain the expertise needed to make technology investments stick.

Boards can also be powerful allies, helping leaders determine when to make and who should be the first tech hire and ensuring talent investments align with mission and strategy. For added expertise, organizations like Board.dev help boards become strong stewards of technology through governance training, practical tools and standards, and the curated placement of tech leaders on nonprofit boards, boosting sector-wide tech capacity.

4. Build Skills to Effectively Use Tech Tools

Tools alone aren’t enough. Nonprofits need the skills to use them effectively. The Center for Effective Philanthropy and Fast Forward both highlight this gap: more than half of nonprofit leaders say staff lack expertise to use or even learn about AI, and 41 percent of AI-powered nonprofits cite lack of in-house technical expertise as a barrier.

Funders can help by supporting both access to tools and the human capacity to adopt, adapt, and sustain them effectively. This includes training programs that build digital literacy, AI fluency, and data-driven decision-making skills to help staff understand how to apply technology in mission-aligned, context-specific ways. In parallel, funders can co-finance governance capacity by supporting board training, AI policy sprints, and incident-response planning, so that grantees have the structures they need to sustain technology over time.

Intermediaries like TechChange, NTEN, TechSoup, Decoded Futures, Project Evident, and The AI for Nonprofits Sprint offer hands-on training, peer support, and mentorship to bridge the gap between adoption and implementation. Meanwhile, “DIY” resources such as OpenAI Academy’s AI for Nonprofits to Google’s Gemini for nonprofits and Microsoft’s resource hub provide free or low-cost entry points for experimentation and learning.

While these tools are valuable, nonprofits often need contextual guidance to use them effectively. This is especially critical for nonprofits that serve historically marginalized communities, which risk being left behind without targeted investments in staff capacity.

5. Funders: Invest in Your Own Tech Talent and Know-How

Not every funder has the capacity to guide technology initiatives and many grantmaking teams lack the expertise to assess and support digital investments. But building tech talent internally can help close that gap.

We have seen that this capacity building can take many forms. It might mean hiring dedicated advisors, embedding tech-savvy leaders into grantmaking teams, or appointing board members with digital transformation experience (such as those trained through Board.dev). Each of these approaches can help funders make more informed decisions and become stronger partners for their grantees.

While competition for digital professionals is intense, the social sector holds a powerful advantage: purpose. Many technologists are seeking roles that align with their values and offer a sense of contribution beyond profit. By emphasizing mission, collaboration, and long-term impact, funders can attract high-caliber talent motivated by meaning as well as skill.

Peer networks can also help bridge the gaps where hiring full-time staff isn’t feasible. We’ve seen funders benefit from sharing insights and accessing specialized expertise collectively through learning communities. Groups like TAG offer shared practices, resources, and a network of peers to keep pace with evolving tools.

Ultimately, when funders build digital savvy, they are better positioned to champion technology as a driver of mission success and collaborate with nonprofits on long-term strategies for innovation, scale, and sustainability.

Many leading funders are already experimenting with new approaches. Emerson Collective, Ballmer Group, Ford Foundation, and MacArthur Foundation have created core technology leadership roles, some internally focused (e.g., chief technology or information officers) and others embedded in programmatic teams. The Patrick J. McGovern Foundation is going a step further, developing open tools to support the broader social sector, including philanthropy itself.

For funders that want to help nonprofits scale impact, improve efficiency, and prepare for the future, greater investment in technology offers a way forward. We’ve seen that technology becomes a driver of mission success when funders listen closely, fund with flexibility, and resource what truly drives impact.

The authors thank the numerous readers who provided input, including Kevin Barenblat, Karly Nelson, and Nicole Dunn at Fast Forward; Ada Sim at Emerson Collective; Alethea Hannemann at Board.dev; Simon Morfit at Project Evident; Amy Sample Ward at NTEN; Jake Porway at Opportunity AI; Larry Yu and Roger Thompson at Bridgespan; and many others.