From our work across the social sector, we know that small and midsize organizations can have a big impact on social problems—whether locally, nationally, or globally. These organizations are often the ones that cover the last mile of service delivery, know communities most intimately, or build fields by filling gaps unaddressed by larger institutions.

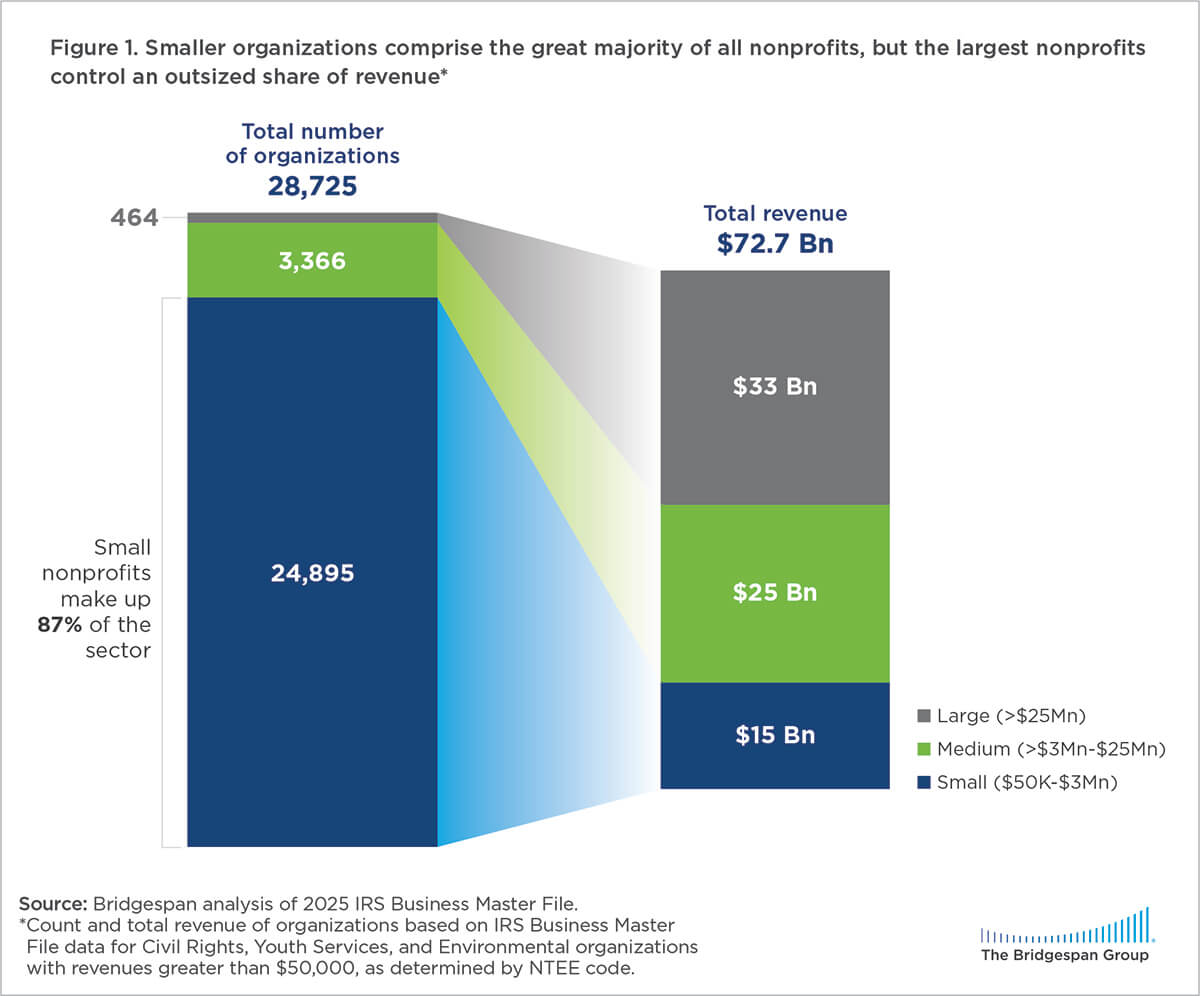

However, the sector is shaped by a stark imbalance of resources. The latest research by our Bridgespan Group team finds that the largest US nonprofits (those with annual revenue over $25 million) raise 45 percent of the nonprofit sector’s revenue—while comprising less than 2 percent of all organizations.

Small organizations (categorized here as those with $3 million and less in annual revenue) make up 87 percent of organizations. Yet together, they raise barely 20 percent of all nonprofit revenue. And as Bridgespan research has shown, organizations led by people of color often face additional barriers to accessing resources, especially philanthropic ones1.

Yet, small and midsize organizations can still build resilient funding strategies to power their programs through good times and bad. In our companion research, we found that most nonprofits in a study sample of 175 organizations raised most of their revenue from a single funding category, such as government, individual donations, or corporate grants. (See “How Small and Midsize US Nonprofits Get Their Funding” for more on funding patterns.)

For this article, we set out to learn how they sustain those funding strategies by interviewing the leaders of 15 small and midsize organizations. We conducted these interviews during a time of exceptional stress for the sector—given federal funding cuts and other uncertainties—and we were first and foremost struck by the vigor and determination of the leaders with whom we spoke. We also found that many small and midsize nonprofits know what their strengths are and use these assets to pursue their funding strategies over time.

We discuss seven of these assets here. Nonprofits deploy different sets of assets, reflecting their unique missions, geographies, histories, and organizational cultures. Some organizations want to grow, while others seek to sustain their work at their current size. And some assets exist from the organization’s creation while others may develop over time. Therefore, not all of these assets will make sense for every organization, and while they may not be surprising, stories from peer organizations provide helpful insight to how they are being used.

Seven Assets of Small and Midsize Nonprofits

- An executive director or CEO who enthusiastically embraces fundraising

- The fortitude to say “no” to potential funding, based on a clear understanding of the strategy and mission

- A board that rolls up its sleeves to support the funding strategy

- Deep roots in the community being served

- Strong capabilities in a programmatic niche—and communicating that excellence

- An appetite for fundraising innovation, experimentation, and risk

- Connections with nonprofit peers

1. An executive director or CEO who enthusiastically embraces fundraising

The executive directors and CEOs we interviewed estimate that, on average, they spend half their time fundraising. (We’ll refer to the leaders as “CEOs” throughout, although they may hold different titles, such as “executive director.”) Often, this is by necessity. Most smaller nonprofits have lean development teams. Some may be lucky to have a single staff person other than the CEO whose job is to raise money.

A leader who embraces fundraising is a powerful asset. “I am the founder, the face, and the brand of the organization. This gives me a level of influence that someone else may not have,” explains Nathaniel Smith, founder and chief equity officer of the Partnership for Southern Equity (PSE), a Georgia-based nonprofit advancing racial equity and shared prosperity across the American South by aligning policy, investment, and grassroots leadership. The Partnership for Southern Equity is a Black-led organization, and Smith’s title reflects its commitment to advancing equity. The organization is predominantly funded by philanthropy, which typically requires a lot of relationship building on the part of the organization’s leader.

Smith's fundraising work combines relationship building with a focus on helping people understand PSE’s work and value. “Philanthropy is not just a foundation, it’s people inside foundations who share your values,” he says. Smith uses his voice, his public presence, and storytelling to draw funders into PSE’s mission. He also believes it helps to be candid with funders about what’s going well and what’s not. “The more we are willing to show them what’s really going on, the more we can help people support us.”

And Smith goes to where the funders are. “The money isn’t going to come in by carrier pigeon. You have to go to events, you have to go where the people are that you want support from, and so some of your budget needs to be for travel.”

Not all leaders start as fundraising powerhouses. “Half my time is fundraising,” says Keri Mitchell, executive director of Dallas Free Press, a nonprofit journalism organization founded in 2020 and focused on historically redlined Dallas neighborhoods. It is funded through a mix of foundations and earned revenue. “I didn’t think I was good at it. Early on I wished there was someone else to take the wheel. But I worked with a coach, and now I’m at the point where I’m completely comfortable telling people, ‘Here’s why you should give us money.’”

Fundraising CEOs come in many forms, and many put a lot of effort into honing their individual strengths. The most important strengths to nurture will depend on the funding category on which the organization mainly relies—government, earned revenue, individual donors, foundations, or corporations. Those who need corporate support but dislike cold-calling, for example, might find they enjoy building personal relationships—which is easier if a leader makes clear the value the organization adds.

And, of course, not all CEOs get energy from fundraising and not all need to be their organization’s chief fundraisers. We know of successful small or midsize nonprofits where most of the fundraising work is carried out by staff, boards, or volunteers, with CEOs supporting that work through their visibility, reputation, or programmatic leadership. Even one or two development staff or volunteers can contribute significantly to the success of a fundraising strategy.

2. The fortitude to say "no" to potential funding, based on a clear understanding of the strategy and mission

One of the pillars of strategy is the word “no.” Clear-eyed leaders will sometimes need to say “no” (or “not now”) to fundraising activities that divert their focus or wander from their mission. Though having this kind of mission clarity isn’t easy in a world where it may seem like malpractice to leave money on the table.

We have written elsewhere of the importance of focus in fundraising. Since nonprofits will likely need to focus on one or two funding categories for the bulk of their revenue, leaders will often need to steer their organizations away from a range of well-intentioned diversions—whether pursuing a new fundraising tactic that a board member is excited about, creating a new program to pick up some grant funding, or stressing over fundraising activities that other organizations are doing.

Occasionally, saying “no” may mean walking away from money. “We use our relationship with funders as a learning opportunity,” explains PSE’s Smith. As chief fundraiser for his organization, he says that sometimes it’s important not to pursue a certain kind of funding if it comes with too many strings or the funder doesn’t seem to understand the work of the organization. “When you’re small or medium-sized, you may need to be courageous to say if the funding doesn’t fit. We are willing to give up funding and opportunities when they do not align with the world we are trying to create.”

The courage to say “no” is often grounded by a leadership team and board that are crystal clear about their organization’s intended impact and how it plans to achieve that impact (what we call “theory of change”). That kind of strategic clarity helps organizations steer clear of mission creep sparked by funding opportunities.

3. A board that rolls up its sleeves to support the funding strategy

The mention of this asset may provoke eye-rolling because some nonprofit boards aren’t well suited to fundraising. CEOs sometimes wish they had more big donors on their board or more members who could bring in donors. And board members occasionally distract from a thoughtful approach by pushing flashy fundraising tactics that other organizations are using (“Let’s host a gala! Let’s run a golf tournament!”).

But there are a variety of ways in which the boards of small and midsize nonprofits can effectively support their organizations’ funding strategies. Consider the California Alliance of Child and Family Services, a nonprofit working to advance policy, practice, and funding solutions for organizations that serve vulnerable children, youth, and families across the state.

Former CEO Christine Stoner-Mertz explains that at one point, the organization recognized the need to move beyond its historic reliance on membership dues as its primary funding source and diversify by generating revenue through training and technical assistance (or TA). “I went to the board. They offered feedback on what types of TA and training are needed and the approach to marketing, and they also supported identifying untapped funding streams like contracts that came from private foundations and state departments.” The board also approved using organizational reserves as seed money for that first TA position with board members’ own donations.

The organization’s budget has grown dramatically since then, fueled substantially by the new focus on TA and training. “It’s been successful because of the expertise we were able to bring to it and the value that people perceive in the TA and training. We leaned on board expertise and their networks to walk confidently into new territory.”

Boards can play a variety of roles. For example, an organization that relies mainly on government funding would value a board that supports it in developing strong contract, compliance, and reporting capabilities—and ideally, a board with connections to key government or other stakeholders who can support the funding strategy. Similarly, an organization that relies heavily on corporate support would benefit from board members who have connections in that world.

4. Deep roots in the community being served

Some government or private funders prefer to support organizations that can demonstrate they understand, represent, and connect with the community in which the work is taking place—whether a neighborhood, a city, or a region.

The Dallas Free Press’s focus on local news and community engagement is central both to its mission and to building its relationship with funders. In its first few years, the organization was supported mainly by national foundations that were interested in exploring the nonprofit model for independent local journalism and its connection to other issues on which those funders were working.

Now, the organization relies much more on local funders—for whom a community connection is especially important. “We emphasize to them how much time we’re spending in local communities,” says Keri Mitchell. “Not everything is a news story. We don’t drop in like the media do. Often, we just show up and listen. The trust that we have earned in the community is our most important currency.”

Some leaders’ backgrounds and identities embody this community understanding and connection. Gloria Ardilla, director of operations, who was raised in West Dallas (a neighborhood on which the Dallas Free Press focuses), notes, “Having someone from the community we were trying to serve helps people feel more motivated, passionate, and connected to what we’re doing.”

Or consider Latinitas, a nonprofit that works in Austin, Texas (and now in San Antonio) to empower girls and their communities through culturally relevant education. For much of its history, the organization was funded primarily by foundations. But in the 2010s, as it shifted its educational focus away from media literacy toward science and math, Latinitas saw a way to connect its work with girls and families in Austin neighborhoods to the longer-term workforce needs of Austin’s growing tech sector. “We asked companies to invest in their community and their future workforce,” says Gabriela Kane, the organization’s executive director. “Over half our budget now comes from corporations, and we still have some of those original corporate partners from years ago.”

Having a strong presence in the community supports the organization’s fundraising in other ways. “There were some foundations that funded us that were explicitly looking for long-standing connection to the community. We were able to show them that, for example, we create our programs with community feedback,” Kane says. The organization also engages affinity groups for Latinos and women in technology at for-profit companies. “We can provide employees with volunteer opportunities, which helps them see our authentic connection to the Latino community and can open the door to funding from the company or its foundation.”

5. Strong capabilities in a programmatic niche—and communicating that excellence

Some small and midsize nonprofits develop expertise and a track record of success in a specific aspect of a broader issue. They may not have the size and breadth of their larger peers, but they are good at what they do and are capable of significant impact despite their smaller size. But the work of such specialized organizations may not be self-explanatory, and so they have to become adept at helping others understand their value and impact.

The Water Finance Exchange (WFX) helps small, rural, and underserved communities in seven Gulf Coast states finance and build affordable, safe drinking water and wastewater systems. The Water Finance Exchange gets the majority of its funding from foundations.

“We have to demonstrate to funders the connection between water and economic opportunity, health, and quality of life,” says Managing Co-Founder Hank Habicht. Equally important, he works to paint a picture of the specific value that WFX creates. Federal and state funding is available to help build water and wastewater infrastructure, but this funding is limited, and many small and underserved communities don’t have the knowledge or capacity to pursue it competitively. The Water Finance Exchange fills that gap by connecting communities to ideas, expertise, and financing options. “By fully addressing financing, we can source public and private funding directly and affordably,” Habicht says. “We also have partners with complementary skill sets, and we work in tandem to access needed capital. Once funders have confidence in what we do and how it helps communities, we can go back to them with additional ideas that need funding.”

Many of the organizations we see that have this asset are, like WFX, intermediaries that offer specific expertise to support on-the-ground organizations in carrying out complex but vital jobs. Others are focused on using technology—or helping others use it—to solve specific problems, such as connecting youth to online mental health support amid the frequently toxic environment of the internet or preserving the cold chain for vaccines and medicines in the least developed parts or the world. These organizations have varying funding strategies—focused on government, fee-for-service, or corporate or foundation funding. But each has found a way to clearly articulate its methods and value for funders.

6. An appetite for fundraising innovation, experimentation, and risk

Organizations of any size can innovate. But smaller organizations can sometimes be more agile, less entrenched, and more willing to experiment and take risks than their larger peers. Even if a current funding strategy is sound, there may be good reasons to experiment. Perhaps there are emerging challenges with large, current funding sources or opportunities within a new one.

Consider Rise Up Together, a US-based initiative founded in 2009 that works through a global network of 800 leaders to advance health, education, economic justice, and gender equity. The organization gets the overwhelming share of its revenue from a combination of foundation and corporate funders. While most nonprofits are best served by focusing on their primary funding category, some can also benefit from developing a secondary category. (See our article “Funding Strategies of Large US Nonprofits” for more on the concept of primary and secondary funding categories.)

“Relying so much on foundations, we didn’t have the unrestricted funding that lets you be freer and more flexible,” explains Denise Raquel Dunning, executive director of Rise Up Together. She wondered if there might be an opportunity to raise unrestricted money from individuals who care about gender equity. “But I didn’t have experience with individual giving. And at the time we were fiscally sponsored, so we didn’t have a board either.”

However, Dunning was willing to experiment, even if it might not pay off. She talked to a peer at another nonprofit about how they built their individual donor base, and her organization’s small size at the time meant they didn’t have any of the institutional lag that many large organizations face. Based on what she learned, she pulled together a leadership council of eight to 10 people who already had some connection to Rise Up Together and were willing to make a gift. “At first, success was just getting a human to write us a check since we’d only ever had support from institutions. But gradually, we learned to build lasting and meaningful relationships that have become invaluable to our work,” Dunning says. In time, council members started bringing in other donors. “Individual giving is still a relatively small proportion of our revenue—about 13 percent. But now we have some individual donors who make larger unrestricted gifts. And since we haven’t had our own board until recently, the leadership council has provided us with strategic guidance and thought partnership, functioning in many ways as a board.”

Innovation in fundraising strategy can start through a chance meeting, a conversation with a colleague or a funder, a bit of information picked up, or sometimes a more structured review of a funding strategy. Experimentation might be adopting new technology or systems, such as AI for donor analysis and prospecting, CRM systems for donor management, or improvements to an organization’s website and social media presence.

There is a fine line between embracing innovation and spreading oneself too thin—even on initiatives that both match a funding strategy and align with organizational strategy and mission (remember how important the ability to say “no” can be). Significant innovations will usually require resources—for example, putting together even a small leadership council, as Rise Up Together did, can take significant thought and effort. And it’s vital to understand when an experiment isn’t paying off—and to call it quits. But smaller organizations without a lot of internal bureaucracy have the chance to innovate faster and learn faster.

7. Connections with nonprofit peers

Peer organizations can be an asset in developing and carrying out a funding strategy. Yes, sometimes an organization may be competing with others for government, corporate, or foundation grants. But there are also opportunities to learn from peers and work together to pursue funding.

We have already seen how the California Alliance of Child and Family Services successfully expanded its funding beyond membership dues. Former CEO Christine Stoner-Mertz recalls how sitting on the board of a national organization that had also moved away from a reliance on dues showed the way for her own organization. “I watched them grow their revenue streams very deliberately. It made me realize that membership organizations like ours actually do have expertise and capacity that, in many ways, doesn’t get seen. I really used their playbook to develop other funding sources.”

There are various ways to learn from or work with peers. Small and midsize organizations, which may lack the capacity to pursue large government or foundation grants on their own, sometimes leverage assets like strong community presence or specific skills or expertise to join with larger ones as partners or subcontractors on a grant. A smaller organization that relies on government funding is unlikely to have its own public affairs person or lobbyist, but organizations often band together to advocate for increased funding.

* * *

This article has focused on ways in which small and midsize nonprofits can use their existing strengths and assets to develop a resilient funding strategy. Over the long run, leaders can also think about how to cultivate their organization’s assets or develop new ones. CEOs can hone their fundraising skills; new board members can be recruited to provide knowledge, skills, or connections that support the organization’s funding strategy; and an organization’s culture can be developed to better support fundraising experimentation and innovation.

An effective funding strategy builds on the strengths an organization already has—and also provides a roadmap for the most important capabilities it needs to nurture over the long term to raise what it needs to continue making a difference in the world.

Ali Kelley is a partner in The Bridgespan Group’s Boston office. Naomi Senbet is a senior manager in the Boston office. Lucia McCurdy is a consultant based in Boston and Cecilia Reis is a senior associate consultant based in Washington, DC. Bradley Seeman is an editorial director based in Boston.