"How am I doing?" the late New York City Mayor Ed Koch used to ask almost everyone he met. And while the mayor was probably looking more for praise than for critical analysis to improve his performance, the nation's largest nonprofits could borrow a page from the mayor's playbook and ask "how am I doing?" about their own performance—especially when it comes to fundraising.

While it's common for large nonprofit networks—such as the YMCA or The Salvation Army—to compare costs and revenues across sites, few have attempted to ask which sites are doing the best job of maximizing fundraising potential—what we call fundraising effectiveness. In other words, is Site A not only raising more money than Site B, but is Site A actually capturing more of the available donor dollars in its community than Site B?1 That kind of comparative analysis can be used to help networks and individual sites learn and adapt best fundraising practices from top performers.

But achieving fundraising effectiveness via comparative analysis will require a shift in thinking. Nonprofits in recent years have spent a lot of time figuring out how to spend limited resources more wisely in an effort to ensure that their programs work—aiming for cost effectiveness. In contrast, comparing sites within a network for potential and effectiveness is somewhat novel. Yet, figuring out how to deliver more dollars per a given demography is just as critical to growing impact as figuring out how to deliver programs that create the most bang for the buck (see "More Bang for the Buck," Stanford Social Innovation Review, Spring 2008).

Given the enormous reach of nonprofit networks, strengthening fundraising effectiveness would bolster resources that affect the lives of hundreds of thousands. Among the 30 largest US nonprofits listed by The Nonprofit Times, 23 are sprawling networks. The top 10 collectively have over 25,000 local sites in communities across all 50 states. And there are hundreds of smaller nonprofit networks operating at the state and regional levels. With their scale and scope, these networks have tremendous ability to address major social issues, such as educational achievement or public health. Fundraising is the fuel that advances these goals.

Improving Fundraising Effectiveness

Despite the importance of fundraising, there is no universally accepted measure of a nonprofit's fundraising performance. By far the most common is whether an organization is raising enough money to cover its costs—essentially, is it making budget, or whether its lowering the cost of raising a dollar. We don't think that either of these goes far enough. Performance against goal, or performance this year compared to last year, doesn't tell you whether fundraising efforts are effective when compared to their potential.

Hence, we propose the following definition of fundraising effectiveness: current fundraising performance compared to fundraising potential as gauged by the pool of donor dollars you draw from. For at least 50 years the corporate world has used a similar comparative analysis, called share of wallet, to measure the amount of customers' total spending that a business captures in the products and services that it offers. "It's very common in our work," said Dianne Ledingham, a leader of Bain & Company's Sales and Channel Effectiveness practice area. "Anytime we work with a multisite or multiproduct organization, we do a share-of-wallet analysis, which, when all the customers are aggregated, is really just share of market." It's an analytical tool that nonprofits can adapt to enhance their fundraising effectiveness.

To date, only a few nonprofit networks have experience with share of wallet.2 The United Way, for example, which has a strong analytical tradition and experience working with the private sector, already uses a form of share of wallet to analyze fundraising performance across its affiliates. But the concept appears to be catching on. The Bridgespan Group, for example, recently worked with several nonprofit networks to adapt the tool, and many others are thinking about how to incorporate it into their fundraising efforts. Sondra Madison, vice president for operations and collaborative strategy at Boys and Girls Clubs of America, noted that "this kind of analysis has come up in our conversations with clubs. We love the idea of this, and on initial review, it shouldn't be too laborious to implement."

Nonprofit networks are drawn to share-of-wallet analysis because it can measure how much individual donors are giving to each network site as a share of total income in the community.3 The network can then compare that measure across sites. This allows for a ranking that takes into account community size and income, giving a truer comparison of how sites are doing at tapping into available resources in that community or service area.4 This kind of data makes it possible for networks to answer three key questions:

- Who are my top performers?

- How much variation is there between sites, and where does it occur?

- How much value is there in raising lower performers to at least the average?

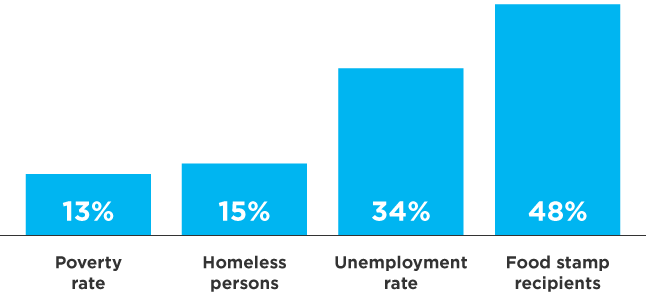

Consider the example of The Salvation Army Empire State Division—comprised of 42 sites across upstate New York, each of which raises some or most of its funds locally. The division in recent years found itself facing a steep challenge in meeting the ever-growing needs of the communities it serves. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1: Need for the Army Is Growing

Est. percent change in Upstate NY, 2008–2012

Having worked hard to cut costs and improve efficiency, the Empire State Division asked how it might improve fundraising performance. Donations from individuals were key. The sites get a significant portion of their fundraising dollars this way, including not only the $10s and $20s that passers-by stuff into The Salvation Army's famous red kettles during the holidays, but also seasonal appeals by direct mail and major donor gifts from affluent supporters. The Division had data on the amount of money each site raised. Unsurprisingly, the biggest cities—Syracuse, Buffalo, and Rochester—raised the most, with budgets several times that of smaller communities like Oswego or Wellsville. But did raising the most mean they were top performers in tapping available local dollars and, as a result, best-practice role models?

Applying Share-of-Wallet Analysis

To answer that question, the Division conducted a share-of-wallet analysis that focused on individual giving (which could also include events, if the revenue was mainly from individuals). It involved six steps. (See "Share-of-Wallet Analysis How-To Guide" and accompanying do-it-yourself analysis spreadsheet.)

Step 1. Identify which categories to analyze within individual giving: The Empire State Division's analysis followed its three distinct revenue streams from individuals—red kettles, seasonal mail appeals, and other donations. For other networks, revenue streams such as fundraising walks or other special events might be the right categories. Some networks may have only a single type of individual-based revenue worth analyzing. Use the categories that are most logical and most comparable across sites for your organization.

Step 2. Collect multiple years of fundraising data: Comparisons for a single year might be thrown off by an outlier, such as one really big gift. The Empire State Division used three years of fundraising data for each site—looking at results for each year, and then across all three years. It found that the top performers in a single year were usually the top performers in the other years as well, suggesting that those sites were using fundraising practices that worked over time.

Step 3. Segment sites into logical groupings: The essence of share-of-wallet analysis is that it allows sites to learn from their peers, so it may make sense to look at comparisons across the entire network and within categories of sites that share similar characteristics. Many networks already have categories in place, and such existing groupings may be the best place to start. The most logical grouping is by size, but for some networks another form of segmentation (by type or region) might also be worthwhile. The Empire State Division divided its 42 sites into five segments based on annual revenue. It then analyzed the data both within segments and across all 42 sites. This allowed Division leaders for the first time to see not only that one small community outperformed another, but that in terms of share of wallet, some smaller towns ones actually outperformed the largest cities.

Step 4. Identify the site boundaries or service areas for which income will be calculated: The Empire State Division had already assigned every zip code in upstate New York to their sites, making analysis easy. If it's necessary to draw geographical boundaries specifically for the share-of-wallet analysis, be sure each site's boundaries incorporate the great of the people it serves and from whom it raises money.

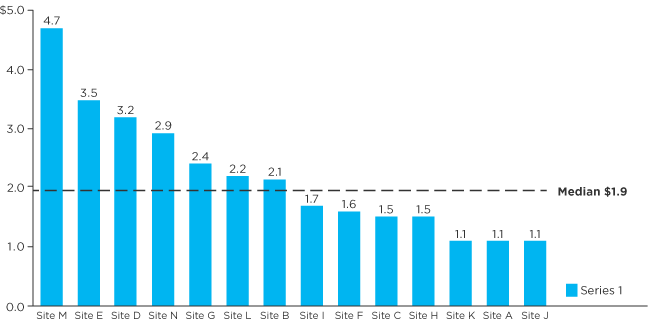

Step 5. Based on income, calculate share of wallet: For each funding category, share of wallet is simply fundraising yield as a share of the income within that site's service area. Because the actual percentage is a very low number, with a lot of zeroes after the decimal point, it's easier to omit the zeroes and express share of wallet as a number greater than one. In the chart below, this is expressed as dollars raised per $100,000 of community income.

The chart depicts how a share-of-wallet analysis might look for a hypothetical group of 14 sites within a network. While the chart does not use actual data from the Empire State Division's analysis, the results reflect the kind of variation they found.

Figure 2: Example Network Share-of-Wallet Analysis: Initial Output

Step 6. Analyze the data: In analyzing the data from the share-of-wallet analysis, it is important to answer whether the findings merit taking action, and what the action priorities should be given that most networks don't have the resources to focus on improving practices everywhere.

Carrying out the analysis proved to be an eye-opener for the Division. Before the analysis "we really didn't look at fundraising potential, just at the current reality," said Paul Cornell, the Division's financial secretary. "I was surprised by what we found. Doing that analysis was revealing," he added. Importantly, it answered the three key questions that any such analysis should address:

Who are my top performers? There were several sites that appeared to be performing much better than the median. In fact, a couple of the Division's smaller sites emerged as the top performers on a share-of-wallet basis, beating out bigger sites. In analyzing share-of-wallet results, it's also important to incorporate information that might explain unexpected variations. In some instances, a particular event or circumstance, such as a funding spike in the wake of a natural disaster, might distort the findings for a site.

How much variation is there and where does it occur? In our hypothetical example, there is a lot of variation (see Figure 2). The top performing site raises a share of wallet more than four times greater than the lowest performing site. Several sites raise a much greater share than the median, and several raise a much lower share. The amount of variation, and where it occurs, combined with judgments about the greatest opportunities for improvement, will help you think about where to invest your time and effort. If the amount of variation is roughly equal across each of several fundraising categories, but one category raises far more than the others, you're likely to want to focus first on that biggest revenue category. If there's only a little variation in some areas but a lot in others, you may want to focus first where there is the most variation—and presumably, the most opportunity for improvement among the lower-performing sites.

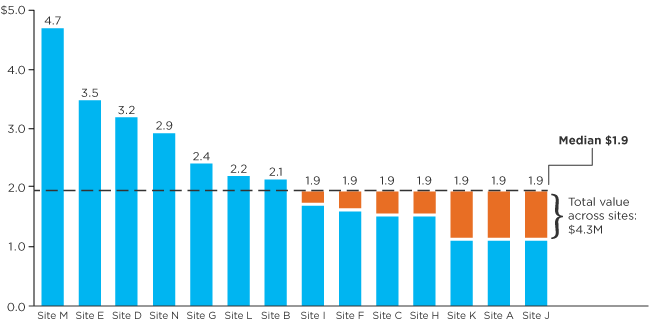

Figure 3: Example Network Share-of-Wallet Analysis: Revenue Potential

How much value is there in raising lower performers to the median? Continuing our hypothetical example, Figure 3 shows this calculation in orange. Raising all the underperformers up to the median would bring in an additional $4.3 million. When the Empire State Division did this same calculation based on its share-of-wallet analysis, it found that getting all the lower performers up to the median could bring in an extra $2 million a year, a very substantial amount of money for the Division. Raising everyone to the median shouldn't necessarily turn into an organizational goal. What's the chance that all the below-average performers could improve? But this calculation helps you understand the scope of the potential gains and how much to invest in the effort.

Learning and Sharing Lessons from Top Performers

Finding your top performers is part of the battle, but the goal is to understand how they achieved their fundraising effectiveness, and to share those lessons with other sites to boost lower performers. To get there, you need to identify which practices might be driving top performers.

Working with the Empire State Division and using the results of its share-of-wallet analysis Bridgespan interviewed officers at the top performing sites to identify fundraising practices that lower performing sites might adapt. We synthesized what we heard, tested these findings with both divisional leaders and a range of site leaders, and identified what might be broadly applicable. For example, we heard about some very specific practices related to the red kettles: where volunteers were sent and which shifts they took (late afternoons and evenings seemed to be especially productive). In addition, the higher performing sites seemed to have a deeper understanding about funders, stakeholders, and partners in their communities, so we developed a community assessment tool that every site could use to strengthen this understanding. And we listened carefully for what wasn't working as well. Two examples: "We don't have a good way to track and analyze our donors," and "We need to think more strategically about donor price points." Based on these identified gaps, we reached outside the network for tools—such as an approach to categorize donors by giving level—that might address these needs.

How a network broadly shares what it has learned from a share-of-wallet analysis also depends on organizational culture and established methods of communication. Regardless of whether a network operates as a single entity—such as The Salvation Army—or a set of independent affiliates, such as the YMCA—sites themselves will need to be partners in a dissemination process that includes the following:

-

Codify practices as concretely as possible. Give examples, adapt tools already in use by one or more sites, or create new ones reflecting best practices or identified needs. For the Empire State Division, the community assessment tool has gotten the greatest traction across the network. "It has really given the officers the opportunity to look at what is happening in their communities," explained Peter Irwin, director of advancement. "It's showing sites what the needs are, where the duplications are, and the strengths and weaknesses in their relationships with their communities."

-

Have peers teach peers the promising practices. But carefully consider who is most likely to learn from whom. The reason for segmenting the share-of-wallet analysis by size or other criteria is so that sites can learn from others whom they consider their peers. As Lynn Hepburn, the chief development officer of Girls Inc., a national network with the mission of inspiring all girls to be strong, smart, and bold, reminded us, "One major challenge in adopting best practices is that smaller sites can't imagine doing the same things that larger sites do."

-

Keep the dissemination process going. Don't stop learning and sharing, including the successes and challenges that emerge as sites seek to adopt some of the practices of the top performers.

The Empire State Division is spreading both the community assessment and donor categorization tools across its network. And the red kettles have been the centerpiece of the Division's performance improvement effort. Division leaders were able to combine insights identified through the share-of-wallet process with a national tool called Kettle Manager, first used by the Empire State Division in 2013, just before its share-of-wallet analysis got underway. Indeed, a particular value of share-of-wallet analysis may be when, as in the case of the red kettles, insights from it connect with and reinforce other efforts already underway in the organization. In 2014, the Empire State Division's improvement efforts helped it chalk up the largest gain in red kettle revenues that year of any of the 40 Salvation Army USA divisions.

Seeing the fundraising results from the improved red kettle practices has been a huge driver of progress within the Empire State Division, said Irwin, the director of advancement. "When Officers start to see the results, it helps them understand that change is important." Beyond giving funding a boost, the share-of-wallet analysis generated insights "about how we should focus our efforts and resources within the Division," said Paul Cornell, the Division's financial secretary. Indeed, share of wallet's days as an analytical method used only by the private-sector may soon pass as more nonprofit networks embrace its power to strengthen their fundraising effectiveness.

Mark McKeag is a manager, and Andrew Flamang a consultant in The Bridgespan Group's Boston office.

Selected Sources (Optional):1. This is not to be confused with the common practice of fundraising yield analysis, whereby nonprofits analyze how many cents they spend to raise a dollar

2. Nonprofit networks are uniquely able to do this because they have a sufficient number of sites to make comparisons useful, and they have access to relevant data for all of those sites.

3. We use income as a proxy for total giving because it is much easier to gather and use.

4. Share of wallet could potentially also be used to compare performance in other funding streams, such as corporate or foundation giving. Though income would probably not be the best denominator, as it is for individual giving. Instead, one would use something like total corporate or foundation giving within a particular community or service area—unlike US Census income data, this isn't as readily available.